High Histamine Foods To Avoid (And Low Histamine Foods To Eat Instead)

10almonds is reader-supported. We may, at no cost to you, receive a portion of sales if you purchase a product through a link in this article.

Nour Zibdeh is an Integrative and Functional Dietician, and she helps people overcome food intolerances. Today, it’s about getting rid of the underdiagnosed condition that is histamine intolerance, by first eliminating the triggers, and then not getting stuck on the low-histamine diet

The recommendations

High histamine foods to avoid include:

- Alcohol (all types)

- Fermented foods—normally great for the gut, but bad in this case

- That includes most cheeses and yogurts

- Aged, cured, or otherwise preserved meat

- Some plants, e.g. tomato, spinach, eggplant, banana, avocado. Again, normally all great, but not in this case.

Low histamine foods to eat include:

- Fruits and vegetables not mentioned above

- Minimally processed meat and fish, either fresh from the butcher/fishmonger, or frozen (not from the chilled food section of the supermarket), and eaten the same day they were purchased or defrosted, because otherwise histamine builds up over time (and quite quickly)

- Grains, but she recommends skipping gluten, given the high likelihood of a comorbid gluten intolerance. So instead she recommends for example quinoa, oats, rice, buckwheat, millet, etc.

For more about these (and more examples), as well as how to then phase safely off the low histamine diet, enjoy:

Click Here If The Embedded Video Doesn’t Load Automatically!

Further reading

Food intolerances often gang up on a person (i.e., comorbidity is high), so you might also like to read about:

- Gluten: What’s The Truth?

- Fiber For FODMAP-Avoiders

- Foods For Managing Hypothyroidism (incl. Hashimoto’s)

- Crohn’s, Food Intolerances, & More

Take care!

Don’t Forget…

Did you arrive here from our newsletter? Don’t forget to return to the email to continue learning!

Recommended

Learn to Age Gracefully

Join the 98k+ American women taking control of their health & aging with our 100% free (and fun!) daily emails:

-

Forks Over Knives: Flavor! – by Darshana Thacker

10almonds is reader-supported. We may, at no cost to you, receive a portion of sales if you purchase a product through a link in this article.

It’s important to not have to choose too much between health and flavor, because the outcome will never be a good one, either for your health or your happiness. And what’s bad for your happiness will ultimately not work out and thus will be bad for your general health, so, the question becomes: how to get both?

This book handles that nicely, delivering plant-based dishes that are also incidentally oil-free, and also either gluten-free or else there’s an obvious easy substitution to make it such. The flavor here comes from the ingredients as a whole, including the main ingredients as well as seasonings.

On the downside, occasionally those ingredients may be a little obscure if you don’t live in, say, San Francisco, and the ingredients weren’t necessarily chosen for cooking on a budget, either.

However, in most cases for most people it will, at worse, inspire you to try using an ingredient you don’t usually use—so that’s a good result.

The recipes are very clear and easy to follow, although not all are illustrated, and the “ready in…” times are about as accurate as they are for any cookbook, that is to say, it’s the time in which it conceivably can be done if (like the author, a head chef) you have a team of sous-chefs who have done a bunch of prep for you (e.g. sweet potato does not normally come in ½” dice; it comes in sweet potatoes) and laid everything out in little bowls mise-en-place style, and also you know the procedure well enough to not have to stop, hesitate, check anything, wash anything, wait for water to boil or anything else to heat up, or so forth. In other words, if you’re on your own in your home kitchen with normal domestic appliances, it’s going to take a little longer than for a professional in a professional kitchen with professional help.

But don’t let that detract from the honestly very good recipes.

Bottom line: if you’d like to level-up your plant-based cooking, this will definitely make your dishes that bit better!

Click here to check out Forks Over Knives: Flavor!, and dig in!

Share This Post

-

Thinking about cosmetic surgery? New standards will force providers to tell you the risks and consider if you’re actually suitable

10almonds is reader-supported. We may, at no cost to you, receive a portion of sales if you purchase a product through a link in this article.

People considering cosmetic surgery – such as a breast augmentation, liposuction or face lift – should have extra protection following the release this week of new safety and quality standards for providers, from small day-clinics through to larger medical organisations.

The new standards cover issues including how these surgeries are advertised, psychological assessments before surgery, the need for people to be informed of risks associated with the procedure, and the type of care people can expect during and afterwards. The idea is for uniform standards across Australia.

The move is part of sweeping reforms of the cosmetic surgery industry and the regulation of medical practitioners, including who is allowed to call themselves a surgeon.

It is heartening to see these reforms, but some may say they should have come much sooner for what’s considered a highly unregulated area of medicine.

Why do people want cosmetic surgery?

Australians spent an estimated A$473 million on cosmetic surgery procedures in 2023.

The major reason people want cosmetic surgery relates to concerns about their body image. Comments from their partners, friends or family about their appearance is another reason.

The way cosmetic surgery is portrayed on social media is also a factor. It’s often portrayed as an “easy” and “accessible” fix for concerns about someone’s appearance. So such aesthetic procedures have become far more normalised.

The use of “before” and “after” images online is also a powerful influence. Some people may think their appearance is worse than the “before” photo and so they think cosmetic intervention is even more necessary.

People don’t always get the results they expect

Most people are satisfied with their surgical outcomes and feel better about the body part that was previously concerning them.

However, people have often paid a sizeable sum of money for these surgeries and sometimes experienced considerable pain as they recover. So a positive evaluation may be needed to justify these experiences.

People who are likely to be unhappy with their results are those with unrealistic expectations for the outcomes, including the recovery period. This can occur if people are not provided with sufficient information throughout the surgical process, but particularly before making their final decision to proceed.

What’s changing?

According to the new standards, services need to ensure their own advertising is not misleading, does not create unreasonable expectations of benefits, does not use patient testimonials, and doesn’t offer any gifts or inducements.

For some clinics, this will mean very little change as they were not using these approaches anyway, but for others this may mean quite a shift in their advertising strategy.

It will likely be a major challenge for clinics to monitor all of their patient communication to ensure they adhere to the standards.

It is also not quite clear how the advertising standards will be monitored, given the expanse of the internet.

What about the mental health assessment?

The new standards say clinics must have processes to ensure the assessment of a patient’s general health, including psychological health, and that information from a patient’s referring doctor be used “where available”.

According to the guidelines from the Medical Board of Australia, which the standards are said to complement, all patients must have a referral, “preferably from their usual general practitioner or if that is not possible, from another general practitioner or other specialist medical practitioner”.

While this is a step in the right direction, we may be relying on medical professionals who may not specialise in assessing body image concerns and related mental health conditions. They may also have had very little prior contact with the patient to make their clinical impressions.

So these doctors need further training to ensure they can perform assessments efficiently and effectively. People considering surgery may also not be forthcoming with these practitioners, and may view them as “gatekeepers” to surgery they really want to have.

Ideally, mental health assessments should be performed by health professionals who are extensively trained in the area. They also know what other areas should be explored with the patient, such as the potential impact of trauma on body image concerns.

Of course, there are not enough mental health professionals, particularly psychologists, to conduct these assessments so there is no easy solution.

Ultimately, this area of health would likely benefit from a standard multidisciplinary approach where all health professionals involved (such as the cosmetic surgeon, general practitioner, dermatologist, psychologist) work together with the patient to come up with a plan to best address their bodily concerns.

In this way, patients would likely not view any of the health professionals as “gatekeepers” but rather members of their treating team.

If you’re considering cosmetic surgery

The Australian Commission on Safety and Quality in Health Care, which developed the new standards, recommended taking these four steps if you’re considering cosmetic surgery:

-

have an independent physical and mental health assessment before you commit to cosmetic surgery

-

make an informed decision knowing the risks

-

choose your practitioner, knowing their training and qualifications

-

discuss your care after your operation and where you can go for support.

My ultimate hope is people safely receive the care to help them best overcome their bodily concerns whether it be medical, psychological or a combination.

Gemma Sharp, Associate Professor, NHMRC Emerging Leadership Fellow & Senior Clinical Psychologist, Monash University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Share This Post

-

-

Infections, Heart Failure, & More

10almonds is reader-supported. We may, at no cost to you, receive a portion of sales if you purchase a product through a link in this article.

Some health news to round off the week:

The Infection That Leads To Heart Failure

It’s long been held that, for example, flossing reduces heart disease risk, with the hypothesis being that if plaque bacteria enter the blood stream, well, that’s an even worse place for plaque bacteria to be. Now, with much more data, attention has turned to

- actual infections, and

- actual heart failure

Way to up the ante! And, it holds true regardless of what kind of infection. So, you might think that a UTI, for example, is surely “downstream” and should not affect the heart, but it does. Because of this, researchers currently believe that it is not the infection itself, so much as the body’s inflammation response to infection, that leads to the heart failure. Which is reasonable, because, for example, atherosclerosis is made mostly not of cholesterol itself, but rather mostly of dead immune cells that got stuck in the cholesterol.

Moreover, it’s not so much about the acute inflammatory response (which is almost always a good thing, circumstantially), but rather that after cases where an infection managed to take hold, the immune system can then often stay on high alert for many years alter. Long COVID is an obvious recent example of this, but it’s hardly a new phenomenon; see for example post-polio syndrome, and consider how many more such post-infection maladies are likely to exist that never got a name because they flew under the radar or got diagnosed as fibromyalgia or something (fibromyalgia is a common diagnosis doctors give when they acknowledge something’s wrong, and it causes pain and exhaustion, but they don’t know what, and it appears to be stable—so while it can be helpful to put a name to the collection of symptoms, it’s a non-diagnosis diagnosis on the doctors’ part. It’s saying “I diagnose you with hurty tiredness”).

The take-away from all this? Avoid infections, for your heart’s sake, and if you do get an infection, take it seriously even if it’s minor. The safe amount of infection is “no infection”.

Read in full: Study uncovers new link between infections and heart failure

Cold Water Immersion: Hot Or Not?

The evidence is clear for some benefits; for others, not so much:

- It’s great (if you’re already in fair health, and definitely not if you have a heart condition) to improve circulation and stress response

- There may be some benefits to immune function, but however reasonable the hypothesis, actual evidence is thin on the ground

- The oft-hyped mood benefits are a) marginal b) short-lived, with benefits fading after 3 months of regular cold baths/showers/etc

Read in full: The big chill: Is cold-water immersion good for our health?

Related: Ice Baths: To Dip Or Not To Dip?

The Unspoken Trials Of Going To The Gym (While Being A Woman)

Public health decision-makers often think that getting people to go to the gym more is a matter of public information, or perhaps branding. Some who have their thinking heads on might even realize that there may be economic factors for many. But for women, there’s an additional factor—or rather, an additionally prominent factor. The study we’ll link started with this observation (please read it in the voice of your favorite nature documentary narrator):

❝Despite an increase in gym memberships, women are less active than men and little is known about the barriers women face when navigating gym spaces.❞

What then, of these shy, elusive creatures that make up a mere 51% of the world’s population?

A medium-sized (n=279) study of women, of whom 84% being current gym-goers, reported often feeling “judged for their appearance or performance, as well as having to fight for space in the gym and to be taken seriously, while navigating harassment and unsolicited comments from men”

Even gym attire becomes an issue:

❝Aligning with previous literature, women often chose attire based on comfort and functionality. However, their choices were also influenced by comparisons with others or fear of judgement for wearing non-branded attire or looking too put together. Many women also chose gym attire to hide perceived problem areas or avoid appearance concerns, including visible sweat stains.❞

…which main seem silly; you’re at the gym, of course you’re going to sweat, but if you’re the only one with visible sweat stains, then there can be social consequences (bad ones).

Similarly, there’s a “damned if you do; damned if you don’t” when it comes to working out while fat—on the one hand, society conflates fatness with laziness; on the other, it can be extra intimidating to be the only fat person in a gym full of people who look like they’re going to audition for a superhero movie.

❝In the gym, just like in other areas of life, women often feel stuck between being seen as ‘too much’ and ‘not enough’, dealing with judgement about how they look, how they perform, and even how much space they take up. Even though the pressure to be super thin is decreasing, the growing focus on being muscular and athletic is creating new challenges. It is pushing unrealistic standards that can negatively affect women’s body image and overall well-being.❞

Writer’s note: I live a few minutes walk from my nearest gym, and I work out at home instead. This way, if I want to do yoga in my pajamas, I can. If I want to use my treadmill naked and watch my T+A bounce in the mirror, I can. If I want to lift weights in the dress I happened to be wearing, I can. Alas that I can’t swim at home!

Read in full: Women face multiple barriers while exercising in gyms

Related: Body Image Dissatisfaction/Appreciation Across The Ages

Take care!

Share This Post

Related Posts

-

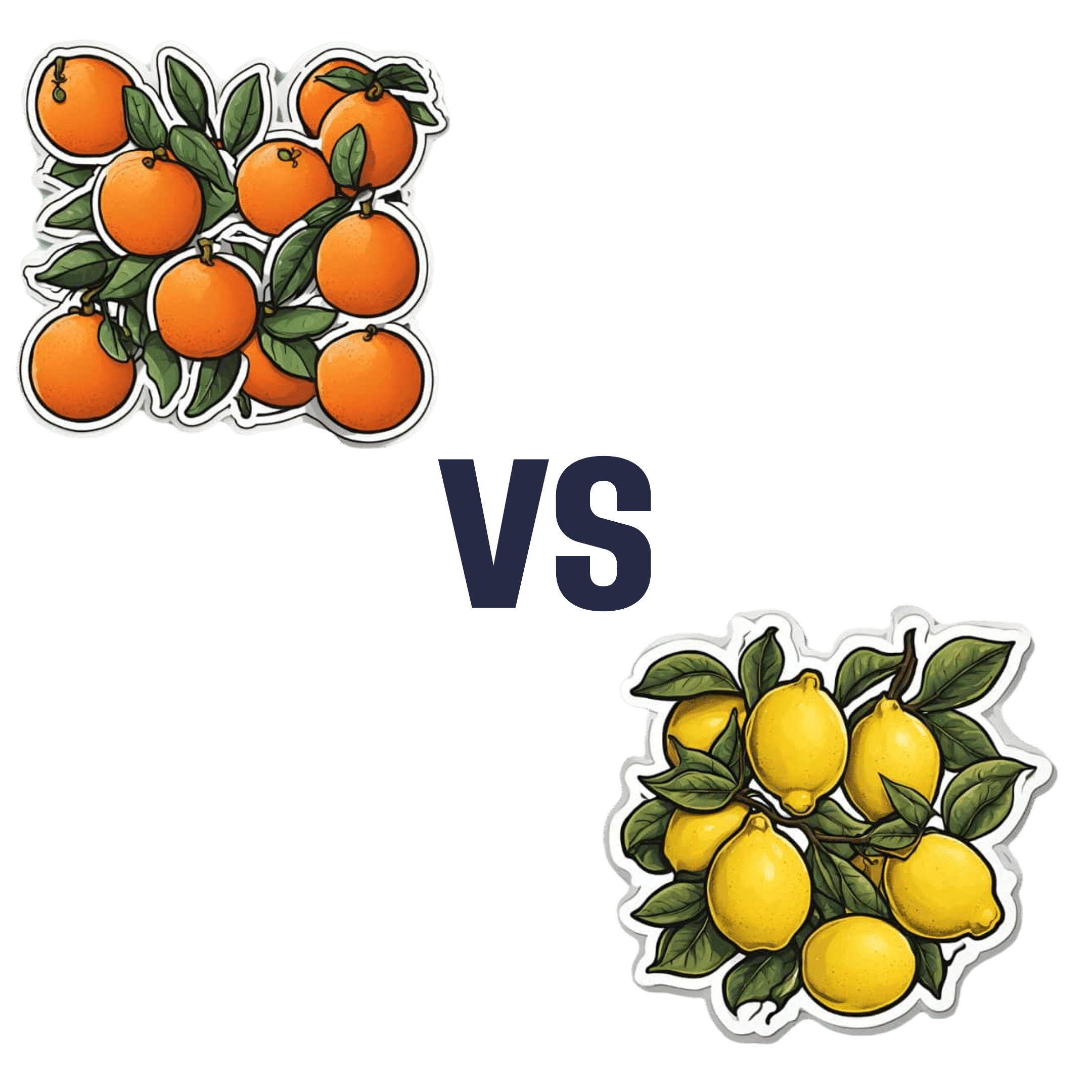

Oranges vs Lemons – Which is Healthier?

10almonds is reader-supported. We may, at no cost to you, receive a portion of sales if you purchase a product through a link in this article.

Our Verdict

When comparing oranges to lemons, we picked the oranges.

Why?

In the battle of these popular citrus fruits, there is a clear winner on the nutritional front.

Things were initially promising for lemons when looking at the macros—lemons have a little more fiber while oranges are slightly higher in carbs, but the differences are small and both are very healthy in this regard.

However, alas for this writer who prefers sour fruits to sweet ones (I’m sweet enough already), the micronutrient profiles tell a different story:

In terms of vitamins, oranges have more of vitamins A, B1, B2, B3, B5, B9, E, and choline. In contrast, lemons have a (very) little more vitamin B6. You might be wondering about vitamin C, since both fruits are famous for that—they’re equal on vitamin C. But, with that stack we listed above, oranges clearly win the vitamin category easily.

As for minerals, oranges boast more calcium, copper, magnesium, potassium, selenium, and zinc, while lemons have more iron, manganese, and phosphorus.

Technically lemons also have more sodium, but the numbers are truly miniscule (by coincidence, we discover upon grabbing a calculator, you’d need to eat approximately your own bodyweight in whole lemons to get to the RDA of sodium—and that’s to reach the RDA, not the upper healthy limit) so we’ll overlook the tiny sodium difference as irrelevant. Which means, while closer than the vitamins category, oranges win on minerals with a 6:3 lead over lemons.

Both fruits offer generous helpings of flavonoids and other polyphenols such as naringenin and hesperidin, which have anti-inflammatory properties and more specifically can also reduce allergy symptoms (unless, of course, you are allergic to citrus fruits, which is a relatively rare but extant allergy).

In short: as ever, enjoy both; diversity is great for the health. But if you want to maximize the nutrients you get, it’s oranges.

Want to learn more?

You might like to read:

Lemons vs Limes – Which is Healthier?

Take care!

Don’t Forget…

Did you arrive here from our newsletter? Don’t forget to return to the email to continue learning!

Learn to Age Gracefully

Join the 98k+ American women taking control of their health & aging with our 100% free (and fun!) daily emails:

-

Unlock Your Flexibility With These 4 New Stretches

10almonds is reader-supported. We may, at no cost to you, receive a portion of sales if you purchase a product through a link in this article.

People often stick to the same few stretches, which may limit flexibility progress, especially as the most common stretches often miss deeper, harder-to-reach areas.

So, here are some new (well, probably new to most people, at least) stretches that can get things moving in different directions:

Diversity Continues To Be Good!

The stretches are:

90/90 Hip stretch with a twist:

- Sit with your knees forming 90° angles; add an arm bar and twist your chest upward.

- Hold for 5 deep breaths and repeat.

- This one targets top glute muscles and quadratus lumborum in the lower back.

Shoulder mobility stretch using a wall:

- Kneel in front of a wall with your forearms placed shoulder-width apart, hands turned outward.

- Lift your hips, push your chest toward your legs, and use the wall and your body weight for deeper leverage.

- This one targets multiple shoulder and rotator cuff muscles through external rotation.

Quad stretch using body weight:

- Sit with your feet hip-width apart, lift your hips, step one foot back, and tuck in your tailbone.

- Focus on pointing your knee down and forward for a deep quad stretch.

- This one targets all four quad muscles, hip flexors, plantar fascia, and opens chest/shoulders.

Chicken wing stretch for upper back:

- Sit with bent knees, place the back of one hand on your waist (chicken wing position).

- Tuck the “wing” into the inner thigh, press your knee inward while resisting with the arm.

- This one broadens the shoulder blade and stretches rear shoulder/upper back muscles; it’s particularly effective for reaching difficult upper back areas not typically stretched.

For more on each of these plus visual demonstrations, enjoy:

Click Here If The Embedded Video Doesn’t Load Automatically!

Want to learn more?

You might also like:

Yoga Teacher: “If I wanted to get flexible in 2025, here’s what I’d do”

Take care!

Don’t Forget…

Did you arrive here from our newsletter? Don’t forget to return to the email to continue learning!

Learn to Age Gracefully

Join the 98k+ American women taking control of their health & aging with our 100% free (and fun!) daily emails:

-

Why do I poo in the morning? A gut expert explains

10almonds is reader-supported. We may, at no cost to you, receive a portion of sales if you purchase a product through a link in this article.

No, you’re not imagining it. People really are more likely to poo in the morning, shortly after breakfast. Researchers have actually studied this.

But why mornings? What if you tend to poo later in the day? And is it worth training yourself to be a morning pooper?

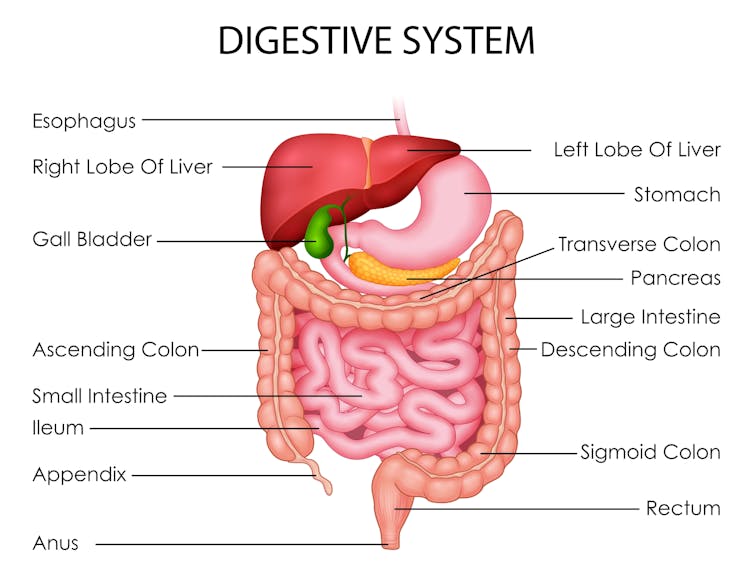

To understand what makes us poo when we do, we need to consider a range of factors including our body clock, gut muscles and what we have for breakfast.

Here’s what the science says.

H_Ko/Shutterstock So morning poos are real?

In a UK study from the early 1990s, researchers asked nearly 2,000 men and women in Bristol about their bowel habits.

The most common time to poo was in the early morning. The peak time was 7-8am for men and about an hour later for women. The researchers speculated that the earlier time for men was because they woke up earlier for work.

About a decade later, a Chinese study found a similar pattern. Some 77% of the almost 2,500 participants said they did a poo in the morning.

But why the morning?

There are a few reasons. The first involves our circadian rhythm – our 24-hour internal clock that helps regulate bodily processes, such as digestion.

For healthy people, our internal clock means the muscular contractions in our colon follow a distinct rhythm.

There’s minimal activity in the night. The deeper and more restful our sleep, the fewer of these muscle contractions we have. It’s one reason why we don’t tend to poo in our sleep.

Your lower gut is a muscular tube that contracts more strongly at certain times of day. Vectomart/Shutterstock But there’s increasing activity during the day. Contractions in our colon are most active in the morning after waking up and after any meal.

One particular type of colon contraction partly controlled by our internal clock are known as “mass movements”. These are powerful contractions that push poo down to the rectum to prepare for the poo to be expelled from the body, but don’t always result in a bowel movement. In healthy people, these contractions occur a few times a day. They are more frequent in the morning than in the evening, and after meals.

Breakfast is also a trigger for us to poo. When we eat and drink our stomach stretches, which triggers the “gastrocolic reflex”. This reflex stimulates the colon to forcefully contract and can lead you to push existing poo in the colon out of the body. We know the gastrocolic reflex is strongest in the morning. So that explains why breakfast can be such a powerful trigger for a bowel motion.

Then there’s our morning coffee. This is a very powerful stimulant of contractions in the sigmoid colon (the last part of the colon before the rectum) and of the rectum itself. This leads to a bowel motion.

How important are morning poos?

Large international surveys show the vast majority of people will poo between three times a day and three times a week.

This still leaves a lot of people who don’t have regular bowel habits, are regular but poo at different frequencies, or who don’t always poo in the morning.

So if you’re healthy, it’s much more important that your bowel habits are comfortable and regular for you. Bowel motions do not have to occur once a day in the morning.

Morning poos are also not a good thing for everyone. Some people with irritable bowel syndrome feel the urgent need to poo in the morning – often several times after getting up, during and after breakfast. This can be quite distressing. It appears this early-morning rush to poo is due to overstimulation of colon contractions in the morning.

Can you train yourself to be regular?

Yes, for example, to help treat constipation using the gastrocolic reflex. Children and elderly people with constipation can use the toilet immediately after eating breakfast to relieve symptoms. And for adults with constipation, drinking coffee regularly can help stimulate the gut, particularly in the morning.

A disturbed circadian rhythm can also lead to irregular bowel motions and people more likely to poo in the evenings. So better sleep habits can not only help people get a better night’s sleep, it can help them get into a more regular bowel routine.

A regular morning coffee can help relieve constipation. Caterina Trimarchi/Shutterstock Regular physical activity and avoiding sitting down a lot are also important in stimulating bowel movements, particularly in people with constipation.

We know stress can contribute to irregular bowel habits. So minimising stress and focusing on relaxation can help bowel habits become more regular.

Fibre from fruits and vegetables also helps make bowel motions more regular.

Finally, ensuring adequate hydration helps minimise the chance of developing constipation, and helps make bowel motions more regular.

Monitoring your bowel habits

Most of us consider pooing in the morning to be regular. But there’s a wide variation in normal so don’t be concerned if your poos don’t follow this pattern. It’s more important your poos are comfortable and regular for you.

If there’s a major change in the regularity of your bowel habits that’s concerning you, see your GP. The reason might be as simple as a change in diet or starting a new medication.

But sometimes this can signify an important change in the health of your gut. So your GP may need to arrange further investigations, which could include blood tests or imaging.

Vincent Ho, Associate Professor and clinical academic gastroenterologist, Western Sydney University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Don’t Forget…

Did you arrive here from our newsletter? Don’t forget to return to the email to continue learning!

Learn to Age Gracefully

Join the 98k+ American women taking control of their health & aging with our 100% free (and fun!) daily emails: