How To Avoid Slipping Into (Bad) Old Habits

10almonds is reader-supported. We may, at no cost to you, receive a portion of sales if you purchase a product through a link in this article.

Treating Bad Habits Like Addictions

How often have you started a healthy new habit (including if it’s a “quit this previous thing” new habit), only to find that you slip back into your old ways?

We’ve written plenty on habit-forming before, so here’s a quick recap before we continue:

How To Really Pick Up (And Keep!) Those Habits

…and even how to give them a boost:

How To Keep On Keeping On… Long Term!

But how to avoid the relapses that are most likely to snowball?

Borrowing from the psychology of addiction recovery

It’s well known that someone recovering from substance addiction should not have even a small amount of the thing they were addicted to. Not one sip of champagne at a wedding, not one drag of a cigarette, and so forth.

This can go for other bad habits too; make one exception, and suddenly you have a whole string of “exceptions”, and before you know it, it’s not the exception anymore; it’s the new rule—again.

Three things that can help guard against this are:

- Absolutely refuse to romanticize the bad habit. Do not fall for its marketing! And yes, everything has marketing even if not advertising; for example, consider the Platonic ideal of a junk-food-eating couch-potato who is humble, unassuming, agreeable, the almost-holy idea of homely comfort, and why shouldn’t we be comfortable after all, haven’t we earned our chosen hedonism, and so on. It’s seductive, and we need to make the choice to not be seduced by it. In this case for example, yes pleasure is great, but being sick tired and destroying our bodies is not, in fact, pleasurable in the long run. Which brings us to…

- Absolutely refuse to forget why you dropped that behavior in the first place. Remember what it did to you, remember you at your worst. Remember what you feared might become of you if you continued like that. This is something where journaling helps, by the way; remembering our low points helps us to avoid finding ourselves in the same situation again.

- Absolutely refuse to let your guard down due to an overabundance of self-confidence in your future self. We all can easily feel that tomorrow is a mystical land in which all productivity is stored, and also where we are strong, energized, iron-willed, and totally able to avoid making the very mistakes that we are right now in the process of making. Instead, be that strong person now, for the benefit of tomorrow’s you. Because after all, if it’s going to be easy tomorrow, it’s easy now, right?

The above is a very simple, hopefully practical, set of rules to follow. If you like hard science more though, Yale’s Dr. Steven Melemis offers five rules (aimed more directly at addiction recovery, so this may be a big “heavy guns” for some milder habits):

- change your life

- be completely honest

- ask for help

- practice self-care

- don’t bend the rules

You can read his full paper and the studies it’s based on, here:

Relapse Prevention and the Five Rules of Recovery

“What if I already screwed up?”

Draw a line under it, now, and move forwards in the direction you actually want to go.

Here’s a good article, that saves us taking up more space here; it’s very well-written so we do recommend it:

The Abstinence Violation Effect and Overcoming It

this article gives specific, practical advices, including CBT tools to use

Take care!

Don’t Forget…

Did you arrive here from our newsletter? Don’t forget to return to the email to continue learning!

Recommended

Learn to Age Gracefully

Join the 98k+ American women taking control of their health & aging with our 100% free (and fun!) daily emails:

-

Stuck in fight-or-flight mode? 5 ways to complete the ‘stress cycle’ and avoid burnout or depression

10almonds is reader-supported. We may, at no cost to you, receive a portion of sales if you purchase a product through a link in this article.

Can you remember a time when you felt stressed leading up to a big life event and then afterwards felt like a weight had been lifted? This process – the ramping up of the stress response and then feeling this settle back down – shows completion of the “stress cycle”.

Some stress in daily life is unavoidable. But remaining stressed is unhealthy. Chronic stress increases chronic health conditions, including heart disease and stroke and diabetes. It can also lead to burnout or depression.

Exercise, cognitive, creative, social and self-soothing activities help us process stress in healthier ways and complete the stress cycle.

What does the stress cycle look like?

Scientists and researchers refer to the “stress response”, often with a focus on the fight-or-flight reactions. The phrase the “stress cycle” has been made popular by self-help experts but it does have a scientific basis.

The stress cycle is our body’s response to a stressful event, whether real or perceived, physical or psychological. It could be being chased by a vicious dog, an upcoming exam or a difficult conversation.

The stress cycle has three stages:

- stage 1 is perceiving the threat

- stage 2 is the fight-or-flight response, driven by our stress hormones: adrenaline and cortisol

- stage 3 is relief, including physiological and psychological relief. This completes the stress cycle.

Different people will respond to stress differently based on their life experiences and genetics.

Unfortunately, many people experience multiple and ongoing stressors out of their control, including the cost-of-living crisis, extreme weather events and domestic violence.

Remaining in stage 2 (the flight-or-flight response), can lead to chronic stress. Chronic stress and high cortisol can increase inflammation, which damages our brain and other organs.

When you are stuck in chronic fight-or-flight mode, you don’t think clearly and are more easily distracted. Activities that provide temporary pleasure, such as eating junk food or drinking alcohol are unhelpful strategies that do not reduce the stress effects on our brain and body. Scrolling through social media is also not an effective way to complete the stress cycle. In fact, this is associated with an increased stress response.

Stress and the brain

In the brain, chronic high cortisol can shrink the hippocampus. This can impair a person’s memory and their capacity to think and concentrate.

Chronic high cortisol also reduces activity in the prefrontal cortex but increases activity in the amygdala.

The prefrontal cortex is responsible for higher-order control of our thoughts, behaviours and emotions, and is goal-directed and rational. The amygdala is involved in reflexive and emotional responses. Higher amygdala activity and lower prefrontal cortex activity explains why we are less rational and more emotional and reactive when we are stressed.

There are five types of activities that can help our brains complete the stress cycle. https://www.youtube.com/embed/eD1wliuHxHI?wmode=transparent&start=0 It can help to understand how the brain encounters stress.

1. Exercise – its own complete stress cycle

When we exercise we get a short-term spike in cortisol, followed by a healthy reduction in cortisol and adrenaline.

Exercise also increases endorphins and serotonin, which improve mood. Endorphins cause an elated feeling often called “runner’s high” and have anti-inflammatory effects.

When you exercise, there is more blood flow to the brain and higher activity in the prefrontal cortex. This is why you can often think more clearly after a walk or run. Exercise can be a helpful way to relieve feelings of stress.

Exercise can also increase the volume of the hippocampus. This is linked to better short-term and long-term memory processing, as well as reduced stress, depression and anxiety.

2. Cognitive activities – reduce negative thinking

Overly negative thinking can trigger or extend the stress response. In our 2019 research, we found the relationship between stress and cortisol was stronger in people with more negative thinking.

Higher amygdala activity and less rational thinking when you are stressed can lead to distorted thinking such as focusing on negatives and rigid “black-and-white” thinking.

Activities to reduce negative thinking and promote a more realistic view can reduce the stress response. In clinical settings this is usually called cognitive behaviour therapy.

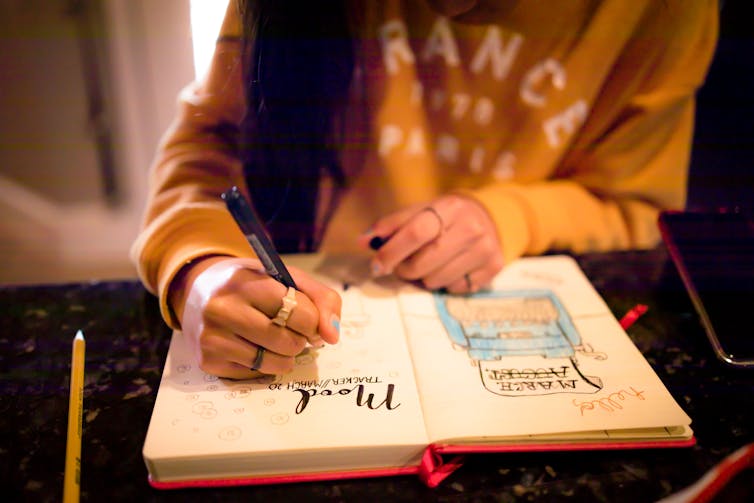

At home, this could be journalling or writing down worries. This engages the logical and rational parts of our brain and helps us think more realistically. Finding evidence to challenge negative thoughts (“I’ve prepared well for the exam, so I can do my best”) can help to complete the stress cycle.

Journalling could help process stressful events and complete the stress cycle. Shutterstock/Fellers Photography 3. Getting creative – a pathway out of ‘flight or fight’

Creative activities can be art, craft, gardening, cooking or other activities such as doing a puzzle, juggling, music, theatre, dancing or simply being absorbed in enjoyable work.

Such pursuits increase prefrontal cortex activity and promote flow and focus.

Flow is a state of full engagement in an activity you enjoy. It lowers high-stress levels of noradrenaline, the brain’s adrenaline. When you are focussed like this, the brain only processes information relevant to the task and ignores non-relevant information, including stresses.

4. Getting social and releasing feel-good hormones

Talking with someone else, physical affection with a person or pet and laughing can all increase oxytocin. This is a chemical messenger in the brain that increases social bonding and makes us feel connected and safe.

Laughing is also a social activity that activates parts of the limbic system – the part of the brain involved in emotional and behavioural responses. This increases endorphins and serotonin and improves our mood.

5. Self-soothing

Breathing exercises and meditation stimulate the parasympathetic nervous system (which calms down our stress responses so we can “reset”) via the vagus nerves, and reduce cortisol.

A good cry can help too by releasing stress energy and increasing oxytocin and endorphins.

Emotional tears also remove cortisol and the hormone prolactin from the body. Our prior research showed cortisol and prolactin were associated with depression, anxiety and hostility.

Getting moving can help with stress and its effects on the brain. Shutterstock/Jaromir Chalabala Action beats distraction

Whether it’s watching a funny or sad movie, exercising, journalling, gardening or doing a puzzle, there is science behind why you should complete the stress cycle.

Doing at least one positive activity every day can also reduce our baseline stress level and is beneficial for good mental health and wellbeing.

Importantly, chronic stress and burnout can also indicate the need for change, such as in our workplaces. However, not all stressful circumstances can be easily changed. Remember help is always available.

If you have concerns about your stress or health, please talk to a doctor.

If this article has raised issues for you, or if you’re concerned about someone you know, call Lifeline on 13 11 14 or Kids Helpline on 1800 55 1800.

Theresa Larkin, Associate professor of Medical Sciences, University of Wollongong and Susan J. Thomas, Associate professor in Mental Health and Behavioural Science, University of Wollongong

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Share This Post

-

What’s the difference between a psychopath and a sociopath? Less than you might think

10almonds is reader-supported. We may, at no cost to you, receive a portion of sales if you purchase a product through a link in this article.

Articles about badly behaved people and how to spot them are common. You don’t have to Google or scroll too much to find headlines such as 7 signs your boss is a psychopath or How to avoid the sociopath next door.

You’ll often see the terms psychopath and sociopath used somewhat interchangeably. That applies to perhaps the most famous badly behaved fictional character of all – Hannibal Lecter, the cannibal serial killer from The Silence of the Lambs.

In the book on which the movie is based, Lecter is described as a “pure sociopath”. But in the movie, he’s described as a “pure psychopath”. Psychiatrists have diagnosed him with something else entirely.

So what’s the difference between a psychopath and a sociopath? As we’ll see, these terms have been used at different times in history, and relate to some overlapping concepts.

Benoit Daoust/Shutterstock What’s a psychopath?

Psychopathy has been mentioned in the psychiatric literature since the 1800s. But the latest edition of the Diagnostic Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (known colloquially as the DSM) doesn’t list it as a recognised clinical disorder.

Since the 1950s, labels have changed and terms such as “sociopathic personality disturbance” have been replaced with antisocial personality disorder, which is what we have today.

Was Hannibal Lecter from The Silence of the Lambs a psychopath, a sociopath or something else entirely? Ralf Liebhold/Shutterstock Someone with antisocial personality disorder has a persistent disregard for the rights of others. This includes breaking the law, repeated lying, impulsive behaviour, getting into fights, disregarding safety, irresponsible behaviours, and indifference to the consequences of their actions.

To add to the confusion, the section in the DSM on antisocial personality disorder mentions psychopathy (and sociopathy) traits. In other words, according to the DSM the traits are part of antisocial personality disorder but are not mental disorders themselves.

US psychiatrist Hervey Cleckley provided the first formal description of psychopathy traits in his 1941 book The Mask of Sanity. He based his description on his clinical observations of nine male patients in a psychiatric hospital. He identified several key characteristics, including superficial charm, unreliability and a lack of remorse or shame.

Canadian psychologist Professor Robert Hare refined these characteristics by emphasising interpersonal, emotional and lifestyle characteristics, in addition to the antisocial behaviours listed in the DSM.

When we draw together all these strands of evidence, we can say a psychopath manipulates others, shows superficial charm, is grandiose and is persistently deceptive. Emotional traits include a lack of emotion and empathy, indifference to the suffering of others, and not accepting responsibility for how their behaviour impacts others.

Finally, a psychopath is easily bored, sponges off others, lacks goals, and is persistently irresponsible in their actions.

So how about a sociopath?

The term sociopath first appeared in the 1930s, and was attributed to US psychologist George Partridge. He emphasised the societal consequences of behaviour that habitually violates the rights of others.

Academics and clinicians often used the terms sociopath and psychopath interchangeably. But some preferred the term sociopath because they said the public sometimes confused the word psychopath with psychosis.

“Sociopathic personality disturbance” was the term used in the first edition of the DSM in 1952. This aligned with the prevailing views at the time that antisocial behaviours were largely the product of the social environment, and that behaviours were only judged as deviant if they broke social, legal, and/or cultural rules.

Some of these early descriptions of sociopathy are more aligned with what we now call antisocial personality disorder. Others relate to emotional characteristics similar to Cleckley’s 1941 definition of a psychopath.

In short, different people had different ideas about sociopathy and, even today, sociopathy is less-well defined than psychopathy. So there is no single definition of sociopathy we can give you, even today. But in general, its antisocial behaviours can be similar to ones we see with psychopathy.

Over the decades, the term sociopathy fell out of favour. From the late 60s, psychiatrists used the term antisocial personality disorder instead.

Born or made?

Both “sociopathy” (what we now call antisocial personality disorder) and psychopathy have been associated with a wide range of developmental, biological and psychological causes.

For example, people with psychopathic traits have certain brain differences especially in regions associated with emotions, inhibition of behaviour and problem solving. They also appear to have differences associated with their nervous system, including a reduced heart rate.

However, sociopathy and its antisocial behaviours are a product of someone’s social environment, and tends to run in families. These behaviours has been associated with physical abuse and parental conflict.

What are the consequences?

Despite their fictional portrayals – such as Hannibal Lecter in Silence of the Lambs or Villanelle in the TV series Killing Eve – not all people with psychopathy or sociopathy traits are serial killers or are physically violent.

But psychopathy predicts a wide range of harmful behaviours. In the criminal justice system, psychopathy is strongly linked with re-offending, particularly of a violent nature.

In the general population, psychopathy is associated with drug dependence, homelessness, and other personality disorders. Some research even showed psychopathy predicted failure to follow COVID restrictions.

But sociopathy is less established as a key risk factor in identifying people at heightened risk of harm to others. And sociopathy is not a reliable indicator of future antisocial behaviour.

In a nutshell

Neither psychopathy nor sociopathy are classed as mental disorders in formal psychiatric diagnostic manuals. They are both personality traits that relate to antisocial behaviours and are associated with certain interpersonal, emotional and lifestyle characteristics.

Psychopathy is thought to have genetic, biological and psychological bases that places someone at greater risk of violating other people’s rights. But sociopathy is less clearly defined and its antisocial behaviours are the product of someone’s social environment.

Of the two, psychopathy has the greatest use in identifying someone who is most likely to cause damage to others.

Bruce Watt, Associate Professor in Psychology, Bond University and Katarina Fritzon, Associate Professor of Psychology, Bond University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Share This Post

-

Mythbusting Moldy Food

10almonds is reader-supported. We may, at no cost to you, receive a portion of sales if you purchase a product through a link in this article.

Most Food Should Not Be Fuzzy

In yesterday’s newsletter, we asked you for your policy when it comes to mold on food (aside from intentional mold, e.g. blue cheese etc), and the responses were interesting:

- About 49% said “throw the whole thing away no matter what it is; it is dangerous”

- About 24% said “cut the mold off and eat the rest of whatever it is”

- The remainder were divided equally between “eat it all; keep the immune system on its toes” and “cut the mold off bread, but moldy animal products are dangerous”

So what does the science say?

Some molds are safe to eat: True or False?

True! We don’t think this is contentious so we’ll not spend much time on it, but just for the sake of being methodical: foods that are supposed to have mold on, including many kinds of cheese and even some kinds of cured meat (salami is an example; that powdery coating is mold).

We could give a big list of safe and unsafe molds, but that would be a list of names and let’s face it, they don’t introduce themselves by name.

However! The litmus test of “is it safe to eat” is:

Did you acquire it with this mold already in place and exactly as expected and advertised?

- If so, it is safe to eat (unless you have an allergy or such)

- If not, it is almost certainly not safe to eat

(more on why, later)

The “sniff test” is a good way to tell if moldy food is bad: True or False?

False. Very false. Because of how the sense of smell works.

You may feel like smell is a way of knowing about something at a distance, but the only way you can smell something is if particles of it are physically connecting with your olfactory receptors inside you. Yes, that has unfortunate implications about bathroom smells, but for now, let’s keep our attention in the kitchen.

If you sniff a moldy item of food, you will now have its mold spores inside your respiratory system. You absolutely do not want them there.

If we cut off the mold, the rest is safe to eat: True or False?

True or False, depending on what it is:

- Hard vegetables (e.g carrots, cabbage), and hard cheeses (e.g. Gruyère, Gouda) – cut off with an inch margin, and it should be safe

- Soft vegetables (e.g. tomatoes, and any vegetables that were hard but are now soft after cooking) – discard entirely; it is unsafe

- Anything else – discard entirely; it is unsafe

The reason for this is because in the case of the hard products mentioned, the mycelium roots of the mold cannot penetrate far.

In the case of the soft products mentioned, the surface mold is “the tip of the iceberg”, and the mycelium roots, which you will not usually be able to see, will penetrate the rest of it.

“Anything else” seems like quite a sweeping statement, but fruits, soft cheeses, yogurt, liquids, jams and jellies, cooked grains and pasta, meats, and yes, bread, are all things where the roots can penetrate deeply and easily. Regardless of you only being able to see a small amount, the whole thing is probably moldy.

The USDA has a handy downloadable factsheet:

Molds On Food: Are They Dangerous?

Eating a little mold is good for the immune system: True or False?

False, generally. There are of course countless types of mold, but not only are many of them pathogenic (mycotoxins), but also, a food that has mold will usually also have pathogenic bacteria along with the mold.

See for example: Occurrence, Toxicity, and Analysis of Major Mycotoxins in Food

Food poisoning will never make you healthier.

But penicillin is safe to eat: True or False?

False, and also penicillin is not the mold on your bread (or other foods).

Penicillin, an antibiotic* molecule, is produced by some species of Penicillium sp., a mold. There are hundreds of known species of Penicillium sp., and most of them are toxic, usually in multiple ways. Take for example:

Penicillium roqueforti PR toxin gene cluster characterization

*it is also not healthy to consume antibiotics unless it is seriously necessary. Antibiotics will wipe out most of your gut’s “good bacteria”, leaving you vulnerable. People have died from C. diff infections for this reason. So obviously, if you really need to take antibiotics, take them as directed, but if not, don’t.

See also: Four Ways Antibiotics Can Kill You

One last thing…

It may be that someone reading this is thinking “I’ve eaten plenty of mold, and I’m fine”. Or perhaps someone you tell about this will say that.

But there are two reasons this logic is flawed:

- Survivorship bias (like people who smoke and live to 102; we just didn’t hear from the 99.9% of people who smoke and die early)

- Being unaware of illness is not being absent of illness. Anyone who’s had an alarming diagnosis of something that started a while ago will know this, of course. It’s also possible to be “low-level ill” often and get used to it as a baseline for health. It doesn’t mean it’s not harmful for you.

Stay safe!

Share This Post

Related Posts

-

What Is “75 Hard”?

10almonds is reader-supported. We may, at no cost to you, receive a portion of sales if you purchase a product through a link in this article.

This is Andy Frisella. He’s not a doctor, scientist, nutritionist, personal trainer, or professional athlete, but he has kicked off a viral fitness challenge, so let’s take a look at it:

What it is

Firstly, Frisella asserts that it’s not a fitness challenge, but rather, he describes it as a “transformative mental toughness program”.

Here’s what it consists of:

- Follow a healthy diet plan with no deviations from it (i.e. no “cheat days”)

- Abstain from alcohol

- Exercise 2x per day, 45 minutes each

- One of the exercise sessions each day must be outside

- No rest days

- Drink 3.5 liters of water per day

And the duration? 75 days, hence the name of the

fitness challengetransformative mental toughness program.Why it is

Frisella’s rationale is:

- we must cultivate mental toughness by doing hard things

- allowing ourselves any deviation would be a sign of mental weakness

- if we allow ourselves to deviate, it becomes a habit

For this reason, he does not “allow” any substitutions, for example if somebody wants to do such-and-such a thing slightly differently instead. We put “allow” in quotation marks because of course, he’s not the boss of you, but per the rules of his challenge, at least.

These reasonings are in and of themselves somewhat sound, however, we at 10almonds would argue:

- before doing hard things, it is good to first consider “is it a good idea?” (amputating your leg using only a spork is a “hard thing”, and demonstrates incredible mental toughness, but that doesn’t make it a good idea)

- while being able to decide to do a thing and then do it is great characteristic to have, it’s good to first consider science; for example, restrictive diets with no flexibility simply do not work, and our bodies do require adequate rest, especially if being pushed through hard things, or problems will happen (injuries, illnesses, etc).

- while it’s true that allowing ourselves to deviate can become a habit, it’s good to first consider what habits we want to make, and make those habits, instead of potentially unsustainable or even simply unpleasant ones.

See also: What Flexible Dieting Really Means: When Flexibility Is The Dish Of The Day

And for that matter: How To Really Pick Up (And Keep!) Those Habits

Want a “75 Gentle” instead?

If you like the idea of making new habits, but are not sure if extreme (and perhaps arbitrary) standards are the ones you want to hold, check out:

Cori Lefkowith’s 25 Healthy Habits That Will Change Your Life

Take care!

Don’t Forget…

Did you arrive here from our newsletter? Don’t forget to return to the email to continue learning!

Learn to Age Gracefully

Join the 98k+ American women taking control of their health & aging with our 100% free (and fun!) daily emails:

-

How Useful Are Our Dreams

10almonds is reader-supported. We may, at no cost to you, receive a portion of sales if you purchase a product through a link in this article.

What’s In A Dream?

We were recently asked:

❝I have a question or a suggestion for coverage in your “Psychology Sunday”. Dreams: their relevance, meanings ( if any) interpretations? I just wondered what the modern psychological opinions are about dreams in general.❞

~ 10almonds subscriber

There are two main schools of thought, and one main effort to reconcile those two. The third one hasn’t quite caught on so far as to be considered a “school of thought” yet though.

The Top-Down Model (Psychoanalysts)

Psychoanalysts broadly follow the theories of Freud, or at least evolved from there. Freud was demonstrably wrong about very many things. Most of his theories have been debunked and ditched—hence the charitable “or at least evolved from there” phrasing when it comes to modern psychoanalytic schools of thought. Perhaps another day, we’ll go into all the ways Freud went wrong. However, for today, one thing he wasn’t bad at…

According to Freud, our dreams reveal our subconscious desires and fears, sometimes directly and sometimes dressed in metaphor.

Examples of literal representations might be:

- sex dreams (revealing our subconscious desires; perhaps consciously we had not thought about that person that way, or had not considered that sex act desirable)

- getting killed and dying (revealing our subconscious fear of death, not something most people give a lot of conscious thought to most of the time)

Examples of metaphorical representations might be:

- dreams of childhood (revealing our subconscious desires to feel safe and nurtured, or perhaps something else depending on the nature of the dream; maybe a return to innocence, or a clean slate)

- dreams of being pursued (revealing our subconscious fear of bad consequences of our actions/inactions, for example, responsibilities to which we have not attended, debts are a good example for many people; or social contact where the ball was left in our court and we dropped it, that kind of thing)

One can read all kinds of guides to dream symbology, and learn such arcane lore as “if you dream of your teeth crumbling, you have financial worries”, but the truth is that “this thing means that other thing” symbolic equations are not only highly personal, but also incredibly culture-bound.

For example:

- To one person, bees could be a symbol of feeling plagued by uncountable small threats; to another, they could be a symbol of abundance, or of teamwork

- One culture’s “crow as an omen of death” is another culture’s “crow as a symbol of wisdom”

- For that matter, in some cultures, white means purity; in others, it means death.

Even such classically Freudian things as dreaming of one’s mother and/or father (in whatever context) will be strongly informed by one’s own waking-world relationship (or lack thereof) with same. Even in Freud’s own psychoanalysis, the “mother” for the sake of such analysis was the person who nurtured, and the “father” was the person who drew the nurturer’s attention away, so they could be switched gender roles, or even different people entirely than one’s parents.

The only real way to know what, if anything, your dreams are trying to tell you, is to ask yourself. You can do that…

- by reflection and personal interrogation (see for example: The Easiest Way To Take Up Journaling)

- or by externalising parts of your subconscious (as in Internal Family Systems therapy)

- or by talking directly to your subconscious where it is, by means of lucid dreaming.

The idea with lucid dreaming is that since any dream character is a facet of your subconscious generated by your own mind, by talking to that character you can ask questions directly of your subconscious (the popular 2010 movie “Inception” was actually quite accurate in this regard, by the way).

To read more about how to do this kind of self-therapy through lucid dreaming, you might want to check out this book we reviewed previously; it is the go-to book of lucid dreaming enthusiasts, and will honestly give you everything you need in one go:

Lucid Dreaming: A Concise Guide to Awakening in Your Dreams and in Your Life – by Dr. Stephen LaBerge

The Bottom-Up Model (Neuroscientists)

This will take a lot less writing, because it’s practically a null hypothesis (i.e., the simplest default assumption before considering any additional evidence that might support or refute it; usually some variant of “nothing unusual going on here”).

The Bottom-Up model holds that our brains run regular maintenance cycles during REM sleep (a biological equivalent of defragging a computer), and the brain interprets these pieces of information flying by and, because of the mind’s tendency to look for patterns, fills in the rest (much like how modern generative AI can “expand” a source image to create more of the same and fill in the blanks), resulting in the often narratively wacky, but ultimately random, vivid hallucinations that we call dreams.

The Hybrid Model (per Cartwright, 2012)

This is really just one woman’s vision, but it’s an incredibly compelling one, that takes the Bottom-Up model and asks “what if we did all that bio-stuff, and then our subconscious mind influenced the interpretation of the random patterns, to create dreams that are subjectively meaningful, and thus do indeed represent our subconscious?

It’s best explained in her own words, though, so it’s time for another book recommendation (we’ve reviewed this one before, too):

Enjoy!

Don’t Forget…

Did you arrive here from our newsletter? Don’t forget to return to the email to continue learning!

Learn to Age Gracefully

Join the 98k+ American women taking control of their health & aging with our 100% free (and fun!) daily emails:

-

Pomegranate vs Cranberries – Which is Healthier?

10almonds is reader-supported. We may, at no cost to you, receive a portion of sales if you purchase a product through a link in this article.

Our Verdict

When comparing pomegranate to cranberries, we picked the pomegranate.

Why?

Starting with the macros: pomegranate has nearly 4x the protein (actually quite a lot for a fruit, but this is not too surprising—it’s because we are eating the seeds!), and slightly more carbs and fiber. Their glycemic indices are comparable, both being low GI foods. While both of these fruits have excellent macro profiles, we say the pomegranate is slightly better, because of the protein, and when it comes to the carbs and fiber, since they balance each other out, we’ll go with the option that’s more nutritionally dense. We like foods that add more nutrients!

In the category of vitamins, pomegranate is higher in vitamins B1, B2, B3, B5, B6, B9, K, and choline, while cranberry is higher in vitamins A, C, and E. Both are very respectable profiles, but pomegranate wins on strength of numbers (and also some higher margins of difference).

When it comes to minerals, it is not close; pomegranate is higher in calcium, copper, iron, magnesium, phosphorus, potassium, selenium, and zinc, while cranberry is higher in manganese. An easy win for pomegranate here.

Both of these fruits have additional “special” properties, though it’s worth noting that:

- pomegranate’s bonus properties, which are too many to list here, but we link to an article below, are mostly in its peel (so dry it, and grind it into a powder supplement, that can be worked into foods, or used like an instant fruit tea, just without the sugar)

- cranberries’ bonus properties (including: famously very good at reducing UTI risk) come with some warnings, including that they may increase the risk of kidney stones if you are prone to such, and also that cranberries have anti-clotting effects, which are great for heart health but can be a risk of you’re on blood thinners or have a bleeding disorder.

You can read about both of these fruits’ special properties in more detail below:

Want to learn more?

You might like to read:

- Health Benefits Of Cranberries (But: You’d Better Watch Out)

- Pomegranate’s Health Gifts Are Mostly In Its Peel

Take care!

Don’t Forget…

Did you arrive here from our newsletter? Don’t forget to return to the email to continue learning!

Learn to Age Gracefully

Join the 98k+ American women taking control of their health & aging with our 100% free (and fun!) daily emails: