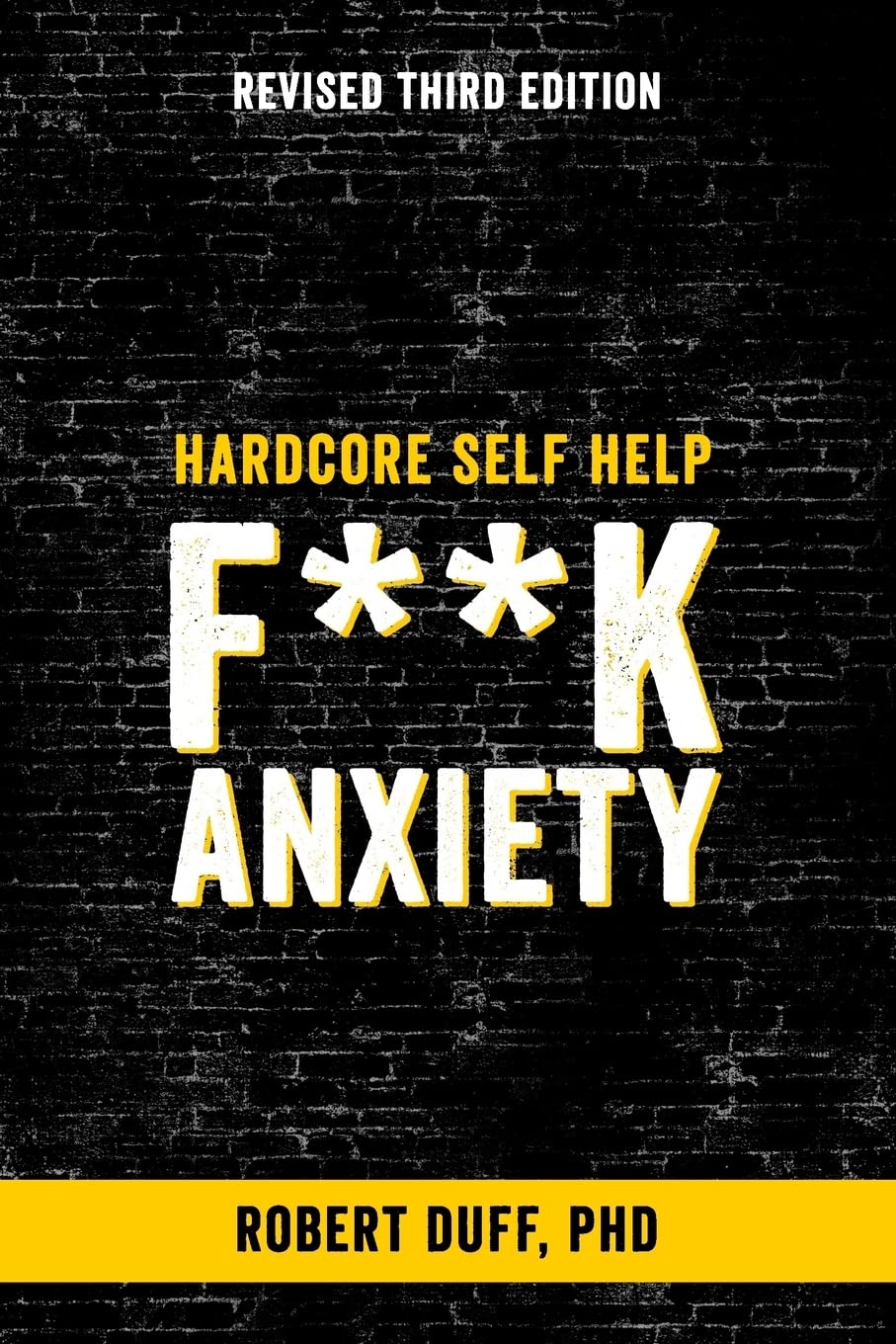

Hardcore Self Help: F**k Anxiety – by Dr. Robert Duff

10almonds is reader-supported. We may, at no cost to you, receive a portion of sales if you purchase a product through a link in this article.

We’ve reviewed other anxiety books before, so what makes this one different? Mostly, it’s the style.

Aside from swearing approximately once every two lines (so you might want to skip this one if that would bother you), Dr. Duff’s writing is very down-to-earth in other ways too, making it unpretentiously comfortable and accessible without failing to draw upon the wealth of good-practice, evidence-based advice he has to offer.

To that end, he talks about what anxiety is and isn’t, and goes over various approaches, explaining them in a “about” fashion, and also a “how to” fashion, covering areas such as CBT, somatic therapies, social support, when talk therapy is most likely to help.

The book is a quick read (a modest 74 pages), and it’s refreshing that it hasn’t been padded unnecessarily, unlike a lot of books that could have been a fraction of the size without losing value.

Bottom line: if you (or perhaps someone you care about) would benefit from a straight-to-the-point, no-BS approach to dealing with anxiety (that’s actually evidence-based, not just a “get over it” dismissal), then this is the book for you.

Click here to check out Hardcore Self Help: F**k Anxiety, and indeed do just that!

Don’t Forget…

Did you arrive here from our newsletter? Don’t forget to return to the email to continue learning!

Recommended

Learn to Age Gracefully

Join the 98k+ American women taking control of their health & aging with our 100% free (and fun!) daily emails:

-

Mental illness, psychiatric disorder or psychological problem. What should we call mental distress?

10almonds is reader-supported. We may, at no cost to you, receive a portion of sales if you purchase a product through a link in this article.

We talk about mental health more than ever, but the language we should use remains a vexed issue.

Should we call people who seek help patients, clients or consumers? Should we use “person-first” expressions such as person with autism or “identity-first” expressions like autistic person? Should we apply or avoid diagnostic labels?

These questions often stir up strong feelings. Some people feel that patient implies being passive and subordinate. Others think consumer is too transactional, as if seeking help is like buying a new refrigerator.

Advocates of person-first language argue people shouldn’t be defined by their conditions. Proponents of identity-first language counter that these conditions can be sources of meaning and belonging.

Avid users of diagnostic terms see them as useful descriptors. Critics worry that diagnostic labels can box people in and misrepresent their problems as pathologies.

Underlying many of these disagreements are concerns about stigma and the medicalisation of suffering. Ideally the language we use should not cast people who experience distress as defective or shameful, or frame everyday problems of living in psychiatric terms.

Our new research, published in the journal PLOS Mental Health, examines how the language of distress has evolved over nearly 80 years. Here’s what we found.

Engin Akyurt/Pexels Generic terms for the class of conditions

Generic terms – such as mental illness, psychiatric disorder or psychological problem – have largely escaped attention in debates about the language of mental ill health. These terms refer to mental health conditions as a class.

Many terms are currently in circulation, each an adjective followed by a noun. Popular adjectives include mental, mental health, psychiatric and psychological, and common nouns include condition, disease, disorder, disturbance, illness, and problem. Readers can encounter every combination.

These terms and their components differ in their connotations. Disease and illness sound the most medical, whereas condition, disturbance and problem need not relate to health. Mental implies a direct contrast with physical, whereas psychiatric implicates a medical specialty.

Mental health problem, a recently emerging term, is arguably the least pathologising. It implies that something is to be solved rather than treated, makes no direct reference to medicine, and carries the positive connotations of health rather than the negative connotation of illness or disease.

Is ‘mental health problem’ actually less pathologising? Monkey Business Images/Shutterstock Arguably, this development points to what cognitive scientist Steven Pinker calls the “euphemism treadmill”, the tendency for language to evolve new terms to escape (at least temporarily) the offensive connotations of those they replace.

English linguist Hazel Price argues that mental health has increasingly come to replace mental illness to avoid the stigma associated with that term.

How has usage changed over time?

In the PLOS Mental Health paper, we examine historical changes in the popularity of 24 generic terms: every combination of the nouns and adjectives listed above.

We explore the frequency with which each term appears from 1940 to 2019 in two massive text data sets representing books in English and diverse American English sources, respectively. The findings are very similar in both data sets.

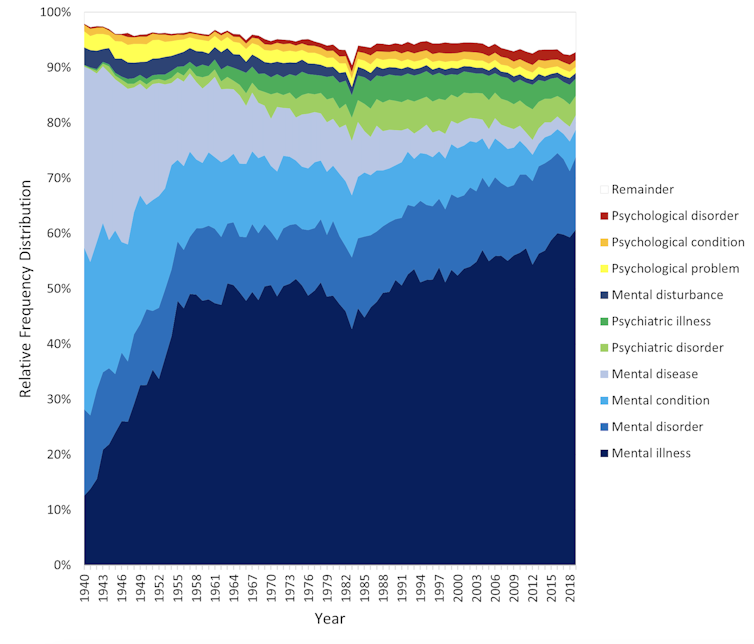

The figure presents the relative popularity of the top ten terms in the larger data set (Google Books). The 14 least popular terms are combined into the remainder.

Relative popularity of alternative generic terms in the Google Books corpus. Haslam et al., 2024, PLOS Mental Health. Several trends appear. Mental has consistently been the most popular adjective component of the generic terms. Mental health has become more popular in recent years but is still rarely used.

Among nouns, disease has become less widely used while illness has become dominant. Although disorder is the official term in psychiatric classifications, it has not been broadly adopted in public discourse.

Since 1940, mental illness has clearly become the preferred generic term. Although an assortment of alternatives have emerged, it has steadily risen in popularity.

Does it matter?

Our study documents striking shifts in the popularity of generic terms, but do these changes matter? The answer may be: not much.

One study found people think mental disorder, mental illness and mental health problem refer to essentially identical phenomena.

Other studies indicate that labelling a person as having a mental disease, mental disorder, mental health problem, mental illness or psychological disorder makes no difference to people’s attitudes toward them.

We don’t yet know if there are other implications of using different generic terms, but the evidence to date suggests they are minimal.

The labels we use may not have a big impact on levels of stigma. Pixabay/Pexels Is ‘distress’ any better?

Recently, some writers have promoted distress as an alternative to traditional generic terms. It lacks medical connotations and emphasises the person’s subjective experience rather than whether they fit an official diagnosis.

Distress appears 65 times in the 2022 Victorian Mental Health and Wellbeing Act, usually in the expression “mental illness or psychological distress”. By implication, distress is a broad concept akin to but not synonymous with mental ill health.

But is distress destigmatising, as it was intended to be? Apparently not. According to one study, it was more stigmatising than its alternatives. The term may turn us away from other people’s suffering by amplifying it.

So what should we call it?

Mental illness is easily the most popular generic term and its popularity has been rising. Research indicates different terms have little or no effect on stigma and some terms intended to destigmatise may backfire.

We suggest that mental illness should be embraced and the proliferation of alternative terms such as mental health problem, which breed confusion, should end.

Critics might argue mental illness imposes a medical frame. Philosopher Zsuzsanna Chappell disagrees. Illness, she argues, refers to subjective first-person experience, not to an objective, third-person pathology, like disease.

Properly understood, the concept of illness centres the individual and their connections. “When I identify my suffering as illness-like,” Chappell writes, “I wish to lay claim to a caring interpersonal relationship.”

As generic terms go, mental illness is a healthy option.

Nick Haslam, Professor of Psychology, The University of Melbourne and Naomi Baes, Researcher – Social Psychology/ Natural Language Processing, The University of Melbourne

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Share This Post

-

To Nap Or Not To Nap; That Is The Question

10almonds is reader-supported. We may, at no cost to you, receive a portion of sales if you purchase a product through a link in this article.

It’s Q&A Day at 10almonds!

Have a question or a request? We love to hear from you!

In cases where we’ve already covered something, we might link to what we wrote before, but will always be happy to revisit any of our topics again in the future too—there’s always more to say!

As ever: if the question/request can be answered briefly, we’ll do it here in our Q&A Thursday edition. If not, we’ll make a main feature of it shortly afterwards!

So, no question/request too big or small

❝Is it good to nap in the afternoon, or better to get the famous 7 to 9 hours at night and leave it at that? I’m worried that daytime napping to make up for a shorter night’s sleep will just perpetuate and worsen it in the long run, is there a categorical answer here?❞

Generally considered best is indeed the 7–9 hours at night (yes, including at older ages):

Why You Probably Need More Sleep

…and sleep efficiency does matter too:

Why 7 Hours Sleep Is Not Enough

…which in turn, is influenced by factors other than just length and depth:

The 6 Dimensions Of Sleep (And Why They Matter)

However! Knowing what is best in theory does not help at all if it’s unattainable in practice. So, if you’re not getting a good night’s sleep (and we’ll assume you’re already practising good sleep hygiene; fresh bedding, lights-off by a certain time, no alcohol or caffeine before bed, that kind of thing), then a first port-of-call may be sleep remedies:

Safe Effective Sleep Aids For Seniors

If even those don’t work, then napping is now likely your best back-up option. But, napping done incorrectly can indeed cause as many problems as it solves. There’s a difference between:

- “I napped and now I have energy again” and you continue with your day

- “Darkness took me, and I strayed out of thought and time. Stars wheeled overhead, and every day was as long as the life age of the earth—but it was not the end.” and now you’re not sure whether it’s day or night, whose house you’re in, or whether you’ve been drugged.

These two very common napping experiences are influenced by factors that we can control:

How To Nap Like A Pro (No More “Sleep Hangovers”!)

If you still prefer to not risk napping but do need at least some kind of refreshment that’s actually a refreshment and not just taking stimulants, then you might consider this practice (from yoga nidra) that gives some of the same benefits of sleep, without actually sleeping:

Non-Sleep Deep Rest: A Neurobiologist’s Insights

Take care!

Share This Post

-

Acid Reflux After Meals? Here’s How To Stop It Naturally

10almonds is reader-supported. We may, at no cost to you, receive a portion of sales if you purchase a product through a link in this article.

Harvard-trained gastroenterologist Dr. Saurabh Sethi advises:

Calming it down

First of all, what it actually is and how it happens: acid reflux occurs when the lower esophageal sphincter (LES) doesn’t close properly, allowing stomach acid to flow back into the esophagus. Chronic acid reflux is known as gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD). Symptoms can include heartburn, an acid taste in the mouth, belching, bloating, sore throat, and a persistent cough—but most people do not get all of the symptoms, usually just some.

Things that help it acutely (as in, you can do them today and they will help today): consider skipping certain foods/substances like peppermint, tomatoes, chocolate, alcohol, and caffeine, which can worsen acid reflux. Eating smaller, more frequent meals instead of large ones and leaving a gap of 3–4 hours before lying down after meals can also help manage symptoms.

Things that can help it chronically (as in, you do them in an ongoing fashion and they will help in an ongoing fashion): lifestyle changes like quitting smoking, reducing alcohol intake, and wearing loose clothing can strengthen the LES. Maintaining a healthy weight and avoiding large meals, especially close to bedtime, can also reduce symptoms. Elevating the upper body while sleeping (using a wedge pillow or raising the bed by 10–20°) can make a big difference.

Medications to avoid, if possible, include: aspirin, ibuprofen, and calcium channel blockers.

Some drinks you can enjoy that will help: drinking water can quickly dilute stomach acid and provide relief. Herbal teas like basil tea, fennel tea, and ginger tea are also effective. But notably: not peppermint tea! Since, as mentioned earlier, peppermint is a known trigger for acid reflux (despite peppermint’s usual digestion-improving properties).

For more on all of this, enjoy:

Click Here If The Embedded Video Doesn’t Load Automatically!

Want to learn more?

You might also like to read:

Coughing/Wheezing After Dinner? Here’s How To Fix It ← this is about acid reflux and more

Take care!

Share This Post

Related Posts

-

How to Be Your Own Therapist – by Owen O’Kane

10almonds is reader-supported. We may, at no cost to you, receive a portion of sales if you purchase a product through a link in this article.

Finding the right therapist can be hard. Sometimes, even just accessing a therapist, any therapist, can be hard, if circumstances are adverse. Sometimes we’d like therapy, but want to feel “better prepared for it” before we do.

Owen O’Kane, a highly qualified and well-respected psychotherapist, wants to put some tools in our hands. The premise of this book is that “in 10 minutes a day” one can give oneself an amount of therapy that will be beneficial.

Naturally, in 10 minutes a day, this isn’t going to be the kind of therapy that will work through major traumas, so what can it do?

Those 10 minutes are spread into three sessions:

- 4 minutes in the morning

- 3 minutes in the afternoon

- 3 minutes in the evening

The idea is:

- To do a quick mental health “check-in” before the day gets started, ascertain what one needs in that context, and make a simple plan to get/have it.

- To keep one’s mental health on track by taking a little pause to reassess and adjust if necessary

- To reflect on the day, amplify the positive, and let go of the negative to what extent is practical, in order to rest well ready for the next day

Where O’Kane excels is in explaining how to do those things in a way that is neither overly simplistic and wishy-washy, nor so arcane and convoluted as to create more work and render the day more difficult.

In short, this book is a great prelude to (or adjunct to) formal therapy, and for those for whom therapy isn’t accessible and/or desired, a great way to keep oneself on a mentally healthy track.

Don’t Forget…

Did you arrive here from our newsletter? Don’t forget to return to the email to continue learning!

Learn to Age Gracefully

Join the 98k+ American women taking control of their health & aging with our 100% free (and fun!) daily emails:

-

A new government inquiry will examine women’s pain and treatment. How and why is it different?

10almonds is reader-supported. We may, at no cost to you, receive a portion of sales if you purchase a product through a link in this article.

The Victorian government has announced an inquiry into women’s pain. Given women are disproportionately affected by pain, such a thorough investigation is long overdue.

The inquiry, the first of its kind in Australia and the first we’re aware of internationally, is expected to take a year. It aims to improve care and services for Victorian girls and women experiencing pain in the future.

The gender pain gap

Globally, more women report chronic pain than men do. A survey of over 1,750 Victorian women found 40% are living with chronic pain.

Approximately half of chronic pain conditions have a higher prevalence in women compared to men, including low back pain and osteoarthritis. And female-specific pain conditions, such as endometriosis, are much more common than male-specific pain conditions such as chronic prostatitis/chronic pelvic pain syndrome.

These statistics are seen across the lifespan, with higher rates of chronic pain being reported in females as young as two years old. This discrepancy increases with age, with 28% of Australian women aged over 85 experiencing chronic pain compared to 18% of men.

It feels worse

Women also experience pain differently to men. There is some evidence to suggest that when diagnosed with the same condition, women are more likely to report higher pain scores than men.

Similarly, there is some evidence to suggest women are also more likely to report higher pain scores during experimental trials where the same painful pressure stimulus is applied to both women and men.

Pain is also more burdensome for women. Depression is twice as prevalent in women with chronic pain than men with chronic pain. Women are also more likely to report more health care use and be hospitalised due to their pain than men.

Women seem to feel pain more acutely and often feel ignored by doctors.

ShutterstockMedical misogyny

Women in pain are viewed and treated differently to men. Women are more likely to be told their pain is psychological and dismissed as not being real or “all in their head”.

Hollywood actor Selma Blair recently shared her experience of having her symptoms repeatedly dismissed by doctors and put down to “menstrual issues”, before being diagnosed with multiple sclerosis in 2018.

It’s an experience familiar to many women in Australia, where medical misogyny still runs deep. Our research has repeatedly shown Australian women with pelvic pain are similarly dismissed, leading to lengthy diagnostic delays and serious impacts on their quality of life.

Misogyny exists in research too

Historically, misogyny has also run deep in medical research, including pain research. Women have been viewed as smaller bodied men with different reproductive functions. As a result, most pre-clinical pain research has used male rodents as the default research subject. Some researchers say the menstrual cycle in female rodents adds additional variability and therefore uncertainty to experiments. And while variability due to the menstrual cycle may be true, it may be no greater than male-specific sources of variability (such as within-cage aggression and dominance) that can also influence research findings.

The exclusion of female subjects in pre-clinical studies has hindered our understanding of sex differences in pain and of response to treatment. Only recently have we begun to understand various genetic, neurochemical, and neuroimmune factors contribute to sex differences in pain prevalence and sensitivity. And sex differences exist in pain processing itself. For instance, in the spinal cord, male and female rodents process potentially painful stimuli through entirely different immune cells.

These differences have relevance for how pain should be treated in women, yet many of the existing pharmacological treatments for pain, including opioids, are largely or solely based upon research completed on male rodents.

When women seek care, their pain is also treated differently. Studies show women receive less pain medication after surgery compared to men. In fact, one study found while men were prescribed opioids after joint surgery, women were more likely to be prescribed antidepressants. In another study, women were more likely to receive sedatives for pain relief following surgery, while men were more likely to receive pain medication.

So, women are disproportionately affected by pain in terms of how common it is and sensitivity, but also in how their pain is viewed, treated, and even researched. Women continue to be excluded, dismissed, and receive sub-optimal care, and the recently announced inquiry aims to improve this.

What will the inquiry involve?

Consumers, health-care professionals and health-care organisations will be invited to share their experiences of treatment services for women’s pain in Victoria as part of the year-long inquiry. These experiences will be used to describe the current service delivery system available to Victorian women with pain, and to plan more appropriate services to be delivered in the future.

Inquiry submissions are now open until March 12 2024. If you are a Victorian woman living with pain, or provide care to Victorian women with pain, we encourage you to submit.

The state has an excellent track record of improving women’s health in many areas, including heart, sexual, and reproductive health, but clearly, we have a way to go with women’s pain. We wait with bated breath to see the results of this much-needed investigation, and encourage other states and territories to take note of the findings.

Jane Chalmers, Senior Lecturer in Pain Sciences, University of South Australia and Amelia Mardon, PhD Candidate, University of South Australia

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Don’t Forget…

Did you arrive here from our newsletter? Don’t forget to return to the email to continue learning!

Learn to Age Gracefully

Join the 98k+ American women taking control of their health & aging with our 100% free (and fun!) daily emails:

-

What Flexible Dieting Really Means

10almonds is reader-supported. We may, at no cost to you, receive a portion of sales if you purchase a product through a link in this article.

When Flexibility Is The Dish Of The Day

This is Alan Aragon. Notwithstanding not being a “Dr. Alan Aragon”, he’s a research scientist with dozens of peer-reviewed nutrition science papers to his name, as well as being a personal trainer and fitness educator. Most importantly, he’s an ardent champion of making people’s pursuit of health and fitness more evidence-based.

We’ll be sharing some insights from a book of his that we haven’t reviewed yet, but we will link it at the bottom of today’s article in any case.

What does he want us to know?

First, get out of the 80s and into the 90s

In the world of popular dieting, the 80s were all about calorie-counting and low-fat diets. They did not particularly help.

In the 90s, it was discovered that not only was low-fat not the way to go, but also, regardless of the diet in question, rigid dieting leads to “disinhibition”, that is to say, there comes a point (usually not far into a diet) whereby one breaks the diet, at which point, the floodgates open and the dieter binges unhealthily.

Aragon would like to bring our attention to a number of studies that found this in various ways over the course of the 90s measuring various different metrics including rigid vs flexible dieting’s impacts on BMI, weight gain, weight loss, lean muscle mass changes, binge-eating, anxiety, depression, and so forth), but we only have so much room here, so here’s a 1999 study that’s pretty much the culmination of those:

Flexible vs. Rigid Dieting Strategies: Relationship with Adverse Behavioral Outcomes

So in short: trying to be very puritan about any aspect of dieting will not only not work, it will backfire.

Next, get out of the 90s into the 00s

…which is not only fun if you read “00s” out loud as “naughties”, but also actually appropriate in this case, because it is indeed important to be comfortable being a little bit naughty:

In 2000, Dr. Marika Tiggemann found that dichotomous perceptions of food (e.g. good/bad, clean/dirty, etc) were implicated as a dysfunctional cognitive style, and predicted not only eating disorders and mood disorders, but also adverse physical health outcomes:

Dieting and Cognitive Style: The Role of Current and Past Dieting Behaviour and Cognitions

This was rendered clearer, in terms of physical health outcomes, by Dr. Susan Byrne & Dr. Emma Dove, in 2009:

❝Weight loss was negatively associated with pre-treatment depression and frequency of treatment attendance, but not with dichotomous thinking. Females who regard their weight as unacceptably high and who think dichotomously may experience high levels of depression irrespective of their actual weight, while depression may be proportionate to the degree of obesity among those who do not think dichotomously❞

Aragon’s advice based on all this: while yes, some foods are better than others, it’s more useful to see foods as being part of a spectrum, rather than being absolutist or “black and white” about it.

Next: hit those perfect 10s… Imperfectly

The next decade expanded on this research, as science is wont to do, and for this one, Aragon shines a spotlight on Dr. Alice Berg’s 2018 study with obese women averaging 69 years of age, in which…

In other words (and in fact, to borrow Dr. Berg’s words from that paper),

❝encouraging a flexible approach to eating behavior and discouraging rigid adherence to a diet may lead to better intentional weight loss for overweight and obese older women❞

You may be wondering: what did this add to the studies from the 90s?

And the key here is: rather than being observational, this was interventional. In other words, rather than simply observing what happened to people who thought one way or another, this study took people who had a rigid, dichotomous approach to food, and gave them a 6-month behavioral intervention (in other words, support encouraging them to be more flexible and open in their approach to food), and found that this indeed improved matters for them.

Which means, it’s not a matter of fate or predisposition, as it could have been back in the 90s, per “some people are just like that; who’s to say which factor causes which”. Instead, now we know that this is an approach that can be adopted, and it can be expected to work.

Beyond weight loss

Now, so far we’ve talked mostly about weight loss, and only touched on other health outcomes. This is because:

- weight loss a very common goal for many

- it’s easy to measure so there’s a lot of science for it

Incidentally, if it’s a goal of yours, here’s what 10almonds had to say about that, along with two follow-up articles for other related goals:

Spoiler: we agree with Aragon, and recommend a relaxed and flexible approach to all three of these things

Aragon’s evidence-based approach to nutrition has found that this holds true for other aspects of healthy eating, too. For example…

To count or not to count?

It’s hard to do evidence-based anything without counting, and so Aragon talks a lot about this. Indeed, he does a lot of counting in scientific papers of his own, such as:

and

The effect of protein timing on muscle strength and hypertrophy: a meta-analysis

…as well as non-protein-related but diet-related topics such as:

But! For the at-home health enthusiast, Aragon recommends that the answer to the question “to count or not to count?” is “both”:

- Start off by indeed counting and tracking everything that is important to you (per whatever your current personal health intervention is, so it might be about calories, or grams of protein, or grams of carbs, or a certain fat balance, or something else entirely)

- Switch to a more relaxed counting approach once you get used to the above. By now you probably know the macros for a lot of your common meals, snacks, etc, and can tally them in your head without worrying about weighing portions and knowing the exact figures.

- Alternatively, count moderately standardized portions of relevant foods, such as “three servings of beans or legumes per day” or “no more than one portion of refined carbohydrates per day”

- Eventually, let habit take the wheel. Assuming you have established good dietary habits, this will now do you just fine.

This latter is the point whereby the advice (that Aragon also champions) of “allow yourself an unhealthy indulgence of 10–20% of your daily food”, as a budget of “discretionary calories”, eventually becomes redundant—because chances are, you’re no longer craving that donut, and at a certain point, eating foods far outside the range of healthiness you usually eat is not even something that you would feel inclined to do if offered.

But until that kicks in, allow yourself that budget of whatever unhealthy thing you enjoy, and (this next part is important…) do enjoy it.

Because it is no good whatsoever eating that cream-filled chocolate croissant and then feeling guilty about it; that’s the dichotomous thinking we had back in the 80s. Decide in advance you’re going to eat and enjoy it, then eat and enjoy it, then look back on it with a sense of “that was enjoyable” and move on.

The flipside of this is that the importance of allowing oneself a “little treat” is that doing so actively helps ensure that the “little treat” remains “little”. Without giving oneself permission, then suddenly, “well, since I broke my diet, I might as well throw the whole thing out the window and try again on Monday”.

On enjoying food fully, by the way:

Mindful Eating: How To Get More Nutrition Out Of The Same Food

Want to know more from Alan Aragon?

Today we’ve been working heavily from this book of his; we haven’t reviewed it yet, but we do recommend checking it out:

Enjoy!

Don’t Forget…

Did you arrive here from our newsletter? Don’t forget to return to the email to continue learning!

Learn to Age Gracefully

Join the 98k+ American women taking control of their health & aging with our 100% free (and fun!) daily emails: