The “Five Tibetan Rites” & Why To Do Them!

10almonds is reader-supported. We may, at no cost to you, receive a portion of sales if you purchase a product through a link in this article.

Spinning Around

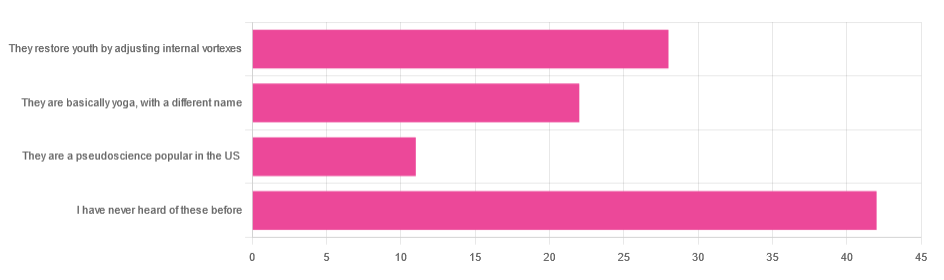

In Tuesday’s newsletter, we asked you for your opinion of the “Five Tibetan Rites”, and got the above-depicted, below-described, set of responses:

- About 41% said “I have never heard of these before”

- About 27% said “they restore youth by adjusting internal vortexes”

- About 22% said “they are basically yoga, by a different name”

- About 11% said “they are a pseudoscience popular in the US”

So what does the science say?

The Five Tibetan Rites are five Tibetan rites: True or False?

False, though this is more question of social science than of health science, so we’ll not count it against them for having a misleading name.

The first known mentioning of the “Five Tibetan Rites” is by an American named Peter Kelder, who in 1939 published, through a small LA occult-specialized publishing house, a booklet called “The Eye of Revelation”. This work was then varyingly republished, repackaged, and occasionally expanded upon by Kelder or other American authors, including Chris Kilham’s popular 1994 book “The Five Tibetans”.

The “Five Tibetan Rites” are unknown as such in Tibet, except for what awareness of them has been raised by people asking about them in the context of the American phenomenon.

Here’s a good history book, for those interested:

The author didn’t originally set out to “debunk” anything, and is himself a keen spiritualist (and practitioner of the five rites), but he was curious about the origins of the rites, and ultimately found them—as a collection of five rites, and the other assorted advices given by Kelder—to be an American synthesis in the whole, each part inspired by various different physical practices (some of them hatha yoga, some from the then-popular German gymnastics movement, some purely American spiritualism, all available in books that were popular in California in the early 1900s).

You may be wondering: why didn’t Kelder just say that, then, instead of telling stories of an ancient Tibetan tradition that empirically does not exist? The answer to this lies again in social science not health science, but it’s been argued that it’s common for Westerners to “pick ‘n’ mix” ideas from the East, champion them as inscrutably mystical, and (since they are inscrutable) then simply decide how to interpret and represent them. Here’s an excellent book on this, if you’re interested:

(in Kelder’s case, this meant that “there’s a Tibetan tradition, trust me” was thus more marketable in the West than “I read these books in LA”)

They are at least five rites: True or False?

True! If we use the broad definition of “rite” as “something done repeatedly in a solemn fashion”. And there are indeed five of them:

- Spinning around (good for balance)

- Leg raises (this one’s from German gymnastics)

- Kneeling back bend (various possible sources)

- Tabletop (hatha yoga, amongst others)

- Pendulum (hatha yoga, amongst others) ← you may recognize this one from the Sun Salutation

You can see them demonstrated here:

Click Here If The Embedded Video Doesn’t Load Automatically

Kelder also advocated for what was basically the Hay Diet (named not for the substance but for William Hay; it involved separating foods into acid and alkali, not necessarily according to the actual pH of the foods, and combining only “acid” foods or only “alkali” foods at a time), which was popular at the time, but has since been rejected as without scientific merit. Kelder referred to this as “the sixth rite”.

The Five Rites restore youth by adjusting internal vortexes: True or False?

False, in any scientific sense of that statement. Scientifically speaking, the body does not have vortexes to adjust, therefore that is not the mechanism of action.

Spiritually speaking, who knows? Not us, a humble health science publication.

The Five Rites are a pseudoscience popular in the US: True or False?

True, if 27% of those who responded of our mostly North American readership can be considered as representative of what is popular.

However…

“Pseudoscience” gets thrown around a lot as a bad word; it’s often used as a criticism, but it doesn’t have to be. Consider:

A small child who hears about “eating the rainbow” and mistakenly understands that we are all fuelled by internal rainbows that need powering-up by eating fruits and vegetables of different colors, and then does so…

…does not hold a remotely scientific view of how things are happening, but is nevertheless doing the correct thing as recommended by our best current science.

It’s thus a little similar with the five rites. Because…

The Five Rites are at least good for our health: True or False?

True! They are great for the health.

The first one (spinning around) is good for balance. Science would recommend doing it both ways rather than just one way, but one is not bad. It trains balance, trains our stabilizing muscles, and confuses our heart a bit (in a good way).

See also: Fall Special (How To Not Fall, And Not Get Injured If You Do)

The second one (leg raises) is excellent for core strength, which in turn helps keep our organs where they are supposed to be (this is a bigger health issue than most people realise, because “out of sight, out of mind”), which is beneficial for many aspects of our health!

See also: Visceral Belly Fat & How To Lose It ← visceral fat is the fat that surrounds your internal organs; too much there becomes a problem!

The third, fourth, and fifth ones stretch our spine (healthily), strengthen our back, and in the cases of the fourth and fifth ones, are good full-body exercises for building strength, and maintaining muscle mass and mobility.

See also: Building & Maintaining Mobility

So in short…

If you’ve been enjoying the Five Rites, by all means keep on doing them; they might not be Tibetan (or an ancient practice, as presented), and any mystical aspect is beyond the scope of our health science publication, but they are great for the health in science-based ways!

Take care!

Don’t Forget…

Did you arrive here from our newsletter? Don’t forget to return to the email to continue learning!

Recommended

Learn to Age Gracefully

Join the 98k+ American women taking control of their health & aging with our 100% free (and fun!) daily emails:

-

52 Weeks to Better Mental Health – by Dr. Tina Tessina

10almonds is reader-supported. We may, at no cost to you, receive a portion of sales if you purchase a product through a link in this article.

We’ve written before about the health benefits of journaling, but how to get started, and how to make it a habit, and what even to write about?

Dr. Tessina presents a year’s worth of journaling prompts with explanations and exercises, and no, they’re not your standard CBT flowchart things, either. Rather, they not only prompt genuine introspection, but also are crafted to be consistently uplifting—yes, even if you are usually the most disinclined to such positivity, and approach such exercises with cynicism.

There’s an element of guidance beyond that, too, and as such, this book is as much a therapist-in-a-book as you might find. Of course, no book can ever replace a competent and compatible therapist, but then, competent and compatible therapists are often harder to find and can’t usually be ordered for a few dollars with next-day shipping.

Bottom line: if undertaken with seriousness, this book will be an excellent investment in your mental health and general wellbeing.

Click here to check out 52 Weeks to Better Mental Health, and get on the best path for you!

Share This Post

-

When Age Is A Flexible Number

10almonds is reader-supported. We may, at no cost to you, receive a portion of sales if you purchase a product through a link in this article.

Aging, Counterclockwise!

In the late 1970s, Dr. Ellen Langer hypothesized that physical markers of aging could be affected by psychosomatic means.

Note: psychosomatic does not mean “it’s all in your head”.

Psychosomatic means “your body does what your brain tells it to do, for better or for worse”

She set about testing that, in what has been referred to since as…

The Counterclockwise Study

A small (n=16) sample of men in their late 70s and early 80s were recruited in what they were told was a study about reminiscing.

Back in the 1970s, it was still standard practice in the field of psychology to outright lie to participants (who in those days were called “subjects”), so this slight obfuscation was a much smaller ethical aberration than in some famous studies of the same era and earlier (cough cough Zimbardo cough Milgram cough).

Anyway, the participants were treated to a week in a 1950s-themed retreat, specifically 1959, a date twenty years prior to the experiment’s date in 1979. The environment was decorated and furnished authentically to the date, down to the food and the available magazines and TV/radio shows; period-typical clothing was also provided, and so forth.

- The control group were told to spend the time reminiscing about 1959

- The experimental group were told to pretend (and maintain the pretense, for the duration) that it really was 1959

The results? On many measures of aging, the experimental group participants became quantifiably younger:

❝The experimental group showed greater improvement in joint flexibility, finger length (their arthritis diminished and they were able to straighten their fingers more), and manual dexterity.

On intelligence tests, 63 percent of the experimental group improved their scores, compared with only 44 percent of the control group. There were also improvements in height, weight, gait, and posture.

Finally, we asked people unaware of the study’s purpose to compare photos taken of the participants at the end of the week with those submitted at the beginning of the study. These objective observers judged that all of the experimental participants looked noticeably younger at the end of the study.❞

Remember, this was after one week.

Her famous study was completed in 1979, and/but not published until eleven years later in 1990, with the innocuous title:

Higher stages of human development: Perspectives on adult growth

You can read about it much more accessibly, and in much more detail, in her book:

Counterclockwise: A Proven Way to Think Yourself Younger and Healthier – by Dr. Ellen Langer

We haven’t reviewed that particular book yet, so here’s Linda Graham’s review, that noted:

❝Langer cites other research that has made similar findings.

In one study, for instance, 650 people were surveyed about their attitudes on aging. Twenty years later, those with a positive attitude with regard to aging had lived seven years longer on average than those with a negative attitude to aging.

(By comparison, researchers estimate that we extend our lives by four years if we lower our blood pressure and reduce our cholesterol.)

In another study, participants read a list of negative words about aging; within 15 minutes, they were walking more slowly than they had before.❞

Read the review in full:

Aging in Reverse: A Review of Counterclockwise

The Counterclockwise study has been repeated since, and/but we are still waiting for the latest (exciting, much larger sample, 90 participants this time) study to be published. The research proposal describes the method in great detail, and you can read that with one click over on PubMed:

It was approved, and has now been completed (as of 2020), but the results have not been published yet; you can see the timeline of how that’s progressing over on ClinicalTrials.gov:

Clinical Trials | Ageing as a Mindset: A Counterclockwise Experiment to Rejuvenate Older Adults

Hopefully it’ll take less time than the eleven years it took for the original study, but in the meantime, there seems to be nothing to lose in doing a little “Citizen Science” for ourselves.

Maybe a week in a 20 years-ago themed resort (writer’s note: wow, that would only be 2004; that doesn’t feel right; it should surely be at least the 90s!) isn’t a viable option for you, but we’re willing to bet it’s possible to “microdose” on this method. Given that the original study lasted only a week, even just a themed date-night on a regular recurring basis seems like a great option to explore (if you’re not partnered then well, indulge yourself how best you see fit, in accord with the same premise; a date-night can be with yourself too!).

Just remember the most important take-away though:

Don’t accidentally put yourself in your own control group!

In other words, it’s critically important that for the duration of the exercise, you act and even think as though it is the appropriate date.

If you instead spend your time thinking “wow, I miss the [decade that does it for you]”, you will dodge the benefits, and potentially even make yourself feel (and thus, potentially, if the inverse hypothesis holds true, become) older.

This latter is not just our hypothesis by the way, there is an established potential for nocebo effect.

For example, the following study looked at how instructions given in clinical tests can be worded in a way that make people feel differently about their age, and impact the results of the mental and/or physical tests then administered:

❝Our results seem to suggest how manipulations by instructions appeared to be more largely used and capable of producing more clear performance variations on cognitive, memory, and physical tasks.

Age-related stereotypes showed potentially stronger effects when they are negative, implicit, and temporally closer to the test of performance. ❞

(and yes, that’s the same Dr. Francesco Pagnini whose name you saw atop the other study we cited above, with the 90 participants recreating the Counterclockwise study)

Want to know more about [the hard science of] psychosomatic health?

Check out Dr. Langer’s other book, which we reviewed recently:

The Mindful Body: Thinking Our Way to Chronic Health – by Dr. Ellen Langer

Enjoy!

Share This Post

-

My dance school is closed for the summer, how can I keep up my fitness?

10almonds is reader-supported. We may, at no cost to you, receive a portion of sales if you purchase a product through a link in this article.

Once the end-of-year dance concert and term wrap up for the year it is important to take a break. Both physical and mental rest are important and taking a few weeks off can help your body repair and have a mental break from dance.

If your mind and body are in need of an extended break (such as more than a few weeks), then it’s more than OK to take longer off, especially if you are training at a competitive or pre-professional level.

There is benefit in enjoying other aspects of your life outside of dance such as spending time with family, friends and enjoying hobbies.

Tatyana Vyc/Shutterstock A safe, fulfilling dancing life

Creating meaning and value in life outside of dance and expanding sense of self can make it easier to lean into other aspects when experiencing change or difficult times during dance training such as being injured.

Taking an extended break from dance training will, however, mean losing some fitness and physical capacity. When you return to dance your body will take time to return to full capacity again.

Approaches such as being “whipped back into shape” can promote sudden spikes in training load (hours and intensity of training) which can increase the risk of injury. It is advised to gradually and progressively increase training load over time to allow the body to adapt and return to full capacity safely.

A four-to-six week period of gradually progressing training load and introducing jumping has been suggested in dance settings.

For dancers wanting to maintain fitness over the summer holidays, a great place to start is focusing on building a physical foundation.

Exercise like running can help build a physical foundation. Jacek Chabraszewski/Shutterstock Building a physical foundation means focusing on targeted areas of fitness such as full body strength, cardiovascular fitness or stamina (such as skipping, cycling walking, running, swimming), flexibility, and some dance-specific conditioning (for example, calf rises for ballet).

A good physical foundation will mean an improved capacity and fitness level so your body is ready to take on more challenging dance movements and routines once you return to the studio.

Building full body strength at home or at the park

A great place to start is by choosing movements that require your muscles to work to support your own body weight.

Fundamental movements such as crawling (moving on the floor on hands and feet) and locomotion (travelling movements such as lunging, hopping, sliding) are great for developing body control, arm and leg stability and coordinated movement patterns.

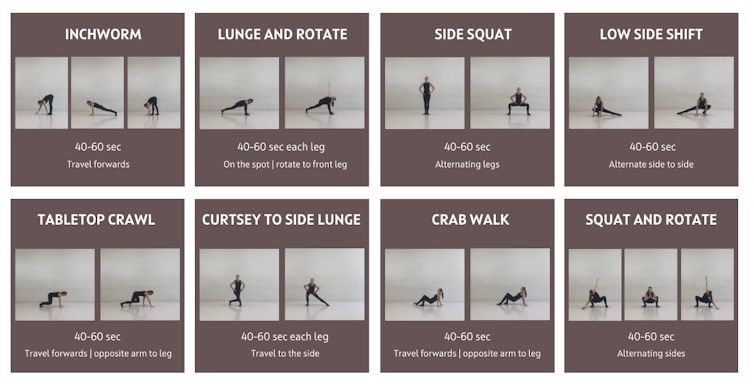

Below is a sequence that can be used as a warm up and even as a workout itself. The ten minute sequence is based on gross motor and fundamental movement patterns. It includes exercises that work through a range of joint movements and in multiple planes (forwards, sideways, rotating).

This fundamental movement sequence can be used as a warm-up or a workout. Joanna Nicholas, CC BY Once feeling comfortable with the above fundamental movements, it is time to introduce body weight resistance exercises.

Body weight resistance exercises can be beneficial for developing a strong foundation for dance movements such as jumping, landing, floorwork, partnering and aerial work.

Exercises from the above sequence can be used to form a safe and effective neuromuscular warm up.

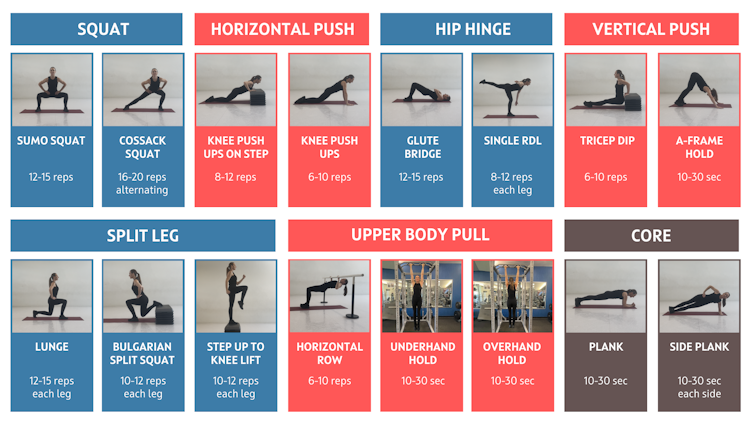

Aim to include one exercise from each of the below movement categories (squat, horizontal push etc) to build your own workout.

Aim to complete two to three sets (or rounds) of each exercise with about one minute rest between sets. An alternative is to complete one set of each exercise with minimal rest between, then complete a second or third time.

If training with friends, you could set a timer and do each exercise for up to 50 seconds (instead of counting reps) and take ten seconds to transition to the next exercise.

Depending on your level of strength you may need to do fewer repetitions and build up sets and repetitions overtime. After you have completed the body weight exercises complete a cool down including stretches for the upper and lower body muscles. Be sure to use a sturdy bar (such as an outdoor fitness station) for horizontal row and overhead hold.

Exercises may need to be modified depending on fitness level and physical limitations such as injury.

You can build your own full body strength workout using these movements. Joanna Nicholas, CC BY How often should I train?

A common misconception in dance is that “more is better”. This belief can lead to dancers training long hours on most or all days of the week which can lead to overtraining, plateauing and increased risk of injury.

Our bodies require sufficient time between training sessions to adapt and get stronger and fitter. The time between sessions is when our muscles and tissues repair and training gains are made.

By incorporating adequate recovery (including sleep and downtime) and including rest days throughout the week, our bodies can gain the most benefits from training.

Rest days are important, too. Manop Boonpeng/Shutterstock Muscles can take up to 48–72 hours to recover from most types of strength-based exercises (the more intense the longer they’ll need to recover).

Aerobic activity at low intensity, such as a brisk walk, can be done most days (24-hour recovery) while high stress anaerobic exercise such as high intensity intervals or sprints can take three days or more to recover from.

Aim to spread training sessions out over the week and allow time to recover between sessions.

Below is an example weekly schedule based on incorporating adequate recovery between sessions, and incorporating polarised training where some days are harder and others are easier.

Seek guidance from your healthcare provider and/or an exercise professional prior to undertaking a new exercise program.

Joanna Nicholas, Lecturer in Dance and Performance Science, Edith Cowan University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Share This Post

Related Posts

-

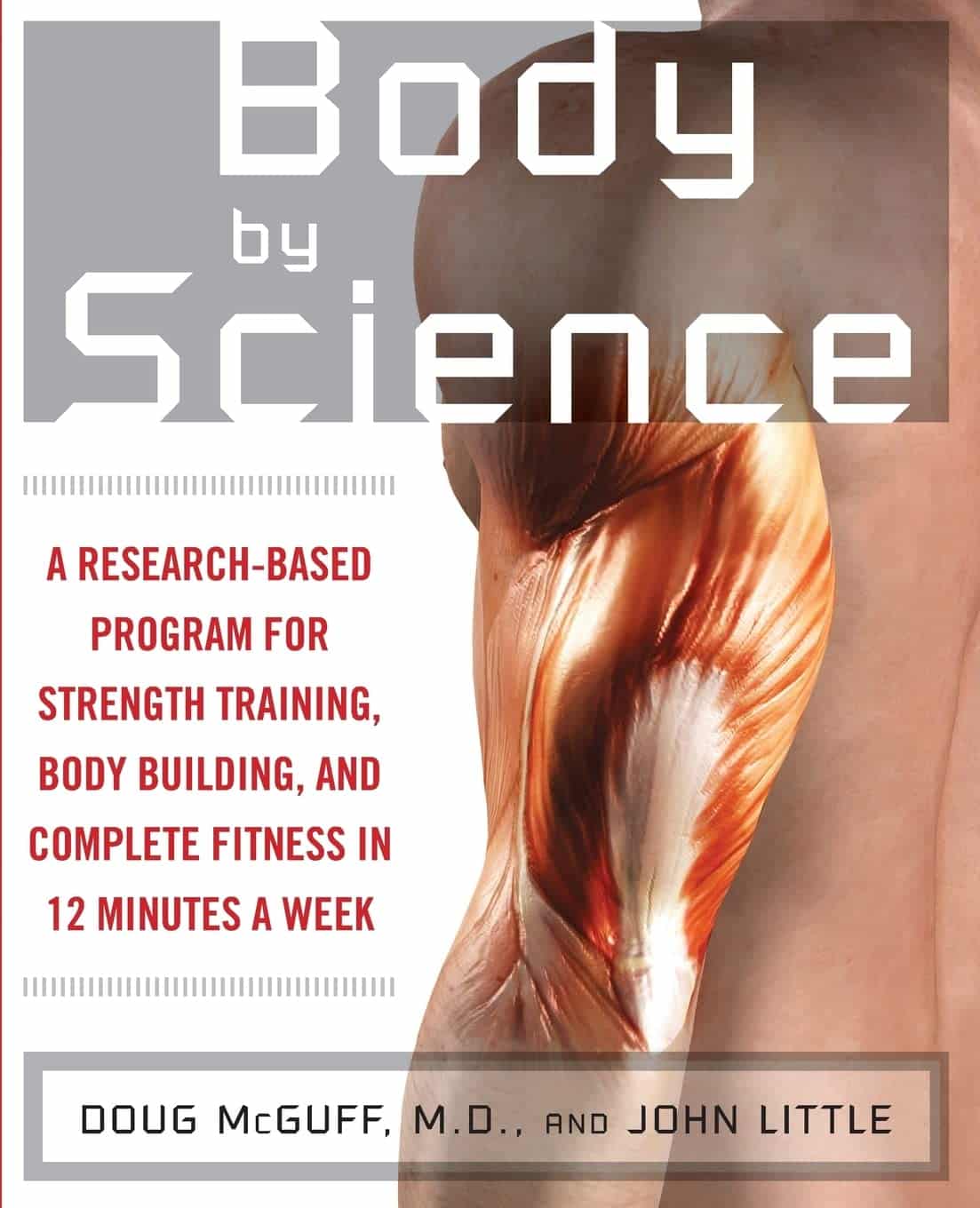

Body by Science – by Dr. Doug McGuff & John Little

10almonds is reader-supported. We may, at no cost to you, receive a portion of sales if you purchase a product through a link in this article.

The idea that you’ll get a re-sculpted body at 12 minutes per week is a bold claim, isn’t it? Medical Doctor Doug McGuff and bodybuilder John Little team up to lay out their case. So, how does it stand up to scrutiny?

First, is it “backed by rigorous research” as claimed? Yes… with caveats.

The book uses a large body of scientific literature as its foundation, and that weight of evidence does support this general approach:

- Endurance cardio isn’t very good at burning fat

- Muscle, even just having it without using it much, burns fat to maintain it

- To that end, muscle can be viewed as a fat-burning asset

- Muscle can be grown quickly with short bursts of intense exercise once per week

Why once per week? The most relevant muscle fibers take about that long to recover, so doing it more often will undercut gains.

So, what are the caveats?

The authors argue for slow reps of maximally heavy resistance work sufficient to cause failure in about 90 seconds. However, most of the studies cited for the benefits of “brief intense exercise” are for High Intensity Interval Training (HIIT). HIIT involves “sprints” of exercise. It doesn’t have to be literally running, but for example maxing out on an exercise bike for 30 seconds, slowing for 60, maxing out for 30, etc. Or in the case of resistance work, explosive (fast!) concentric movements and slow eccentric movements, to work fast- and slow-twitch muscle fibers, respectively.

What does this mean for the usefulness of the book?

- Will it sculpt your body as described in the blurb? Yes, this will indeed grow your muscles with a minimal expenditure of time

- Will it improve your body’s fat-burning metabolism? Yes, this will indeed turn your body into a fat-burning machine

- Will it improve your “complete fitness”? No, if you want to be an all-rounder athlete, you will still need HIIT, as otherwise anything taxing your under-worked fast-twitch muscle fibers will exhaust you quickly.

Bottom line: read this book if you want to build muscle efficiently, and make your body more efficient at burning fat. Best supplemented with at least some cardio, though!

Click here to check out Body by Science, and get re-sculpting yours!

Don’t Forget…

Did you arrive here from our newsletter? Don’t forget to return to the email to continue learning!

Learn to Age Gracefully

Join the 98k+ American women taking control of their health & aging with our 100% free (and fun!) daily emails:

-

Want to sleep longer? Adding mini-bursts of exercise to your evening routine can help – new study

10almonds is reader-supported. We may, at no cost to you, receive a portion of sales if you purchase a product through a link in this article.

Exercising before bed has long been discouraged as the body doesn’t have time to wind down before the lights go out.

But new research has found breaking up a quiet, sedentary evening of watching television with short bursts of resistance exercise can lead to longer periods of sleep.

Adults spend almost one third of the 24-hour day sleeping. But the quality and length of sleep can affect long-term health. Sleeping too little or waking often in the night is associated with an increased risk of heart disease and diabetes.

Physical activity during the day can help improve sleep. However, current recommendations discourage intense exercise before going to bed as it can increase a person’s heart rate and core temperature, which can ultimately disrupt sleep.

Nighttime habits

For many, the longest period of uninterrupted sitting happens at home in the evening. People also usually consume their largest meal during this time (or snack throughout the evening).

Insulin (the hormone that helps to remove sugar from the blood stream) tends to be at a lower level in the evening than in the morning.

Together these factors promote elevated blood sugar levels, which over the long term can be bad for a person’s health.

Our previous research found interrupting evening sitting every 30 minutes with three minutes of resistance exercise reduces the amount of sugar in the bloodstream after eating a meal.

But because sleep guidelines currently discourage exercising in the hours before going to sleep, we wanted to know if frequently performing these short bursts of light activity in the evening would affect sleep.

Activity breaks for better sleep

In our latest research, we asked 30 adults to complete two sessions based in a laboratory.

During one session the adults sat continuously for a four-hour period while watching streaming services. During the other session, they interrupted sitting by performing three minutes of body-weight resistance exercises (squats, calf raises and hip extensions) every 30 minutes.

After these sessions, participants went home to their normal life routines. Their sleep that evening was measured using a wrist monitor.

Our research found the quality of sleep (measured by how many times they woke in the night and the length of these awakenings) was the same after the two sessions. But the night after the participants did the exercise “activity breaks” they slept for almost 30 minutes longer.

Identifying the biological reasons for the extended sleep in our study requires further research.

But regardless of the reason, if activity breaks can extend sleep duration, then getting up and moving at regular intervals in the evening is likely to have clear health benefits.

Time to revisit guidelines

These results add to earlier work suggesting current sleep guidelines, which discourage evening exercise before bed, may need to be reviewed.

As the activity breaks were performed in a highly controlled laboratory environment, future research should explore how activity breaks performed in real life affect peoples sleep.

We selected simple, body-weight exercises to use in this study as they don’t require people to interrupt the show they may be watching, and don’t require a large space or equipment.

If people wanted to incorporate activity breaks in their own evening routines, they could probably get the same benefit from other types of exercise. For example, marching on the spot, walking up and down stairs, or even dancing in the living room.

The key is to frequently interrupt evening sitting time, with a little bit of whole-body movement at regular intervals.

In the long run, performing activity breaks may improve health by improving sleep and post-meal blood sugar levels. The most important thing is to get up frequently and move the body, in a way the works best for a person’s individual household.

Jennifer Gale, PhD candidate, Department of Human Nutrition, University of Otago and Meredith Peddie, Senior Lecturer, Department of Human Nutrition, University of Otago

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Don’t Forget…

Did you arrive here from our newsletter? Don’t forget to return to the email to continue learning!

Learn to Age Gracefully

Join the 98k+ American women taking control of their health & aging with our 100% free (and fun!) daily emails:

-

Sweet Dreams Are Made of THC (Or Are They?)

10almonds is reader-supported. We may, at no cost to you, receive a portion of sales if you purchase a product through a link in this article.

It’s Q&A Day at 10almonds!

Have a question or a request? We love to hear from you!

In cases where we’ve already covered something, we might link to what we wrote before, but will always be happy to revisit any of our topics again in the future too—there’s always more to say!

As ever: if the question/request can be answered briefly, we’ll do it here in our Q&A Thursday edition. If not, we’ll make a main feature of it shortly afterwards!

So, no question/request too big or small 😎

❝I’m one of those older folks that have a hard time getting 7 hrs. I know a lot of it my fault…like a few beers at nite…🥰am now trying THC gummies for anxiety, instead of alcohol……less calories 😁how does THC affect our sleep,? Safer than alcohol…..I know your next article 😊😊😊😊❣️😊alot of us older kids do take gummies 😲😲😲thank you❞

Great question! We wrote a little about CBD gummies (not THC) before:

…and went on to explore THC’s health benefits and risks here:

For starters, let’s go ahead and say: you’re right that it’s safer (for most people) than alcohol—but that’s not a strong claim, because alcohol is very bad for pretty much everything, including sleep.

So how does THC measure up when it comes to sleep quality?

Good news: it affects the architecture of sleep in such a way that you will spend longer in deep sleep (delta wave activity), which means you get more restorative and restful sleep!

See also: Alpha, beta, theta: what are brain states and brain waves? And can we control them?

Bad news: it does so at the cost of reducing your REM sleep, which is also necessary for good brain health, and will cause cognitive impairment if you skip too much. Normally, if you are sleep-deprived, the brain will prioritize REM sleep at the cost of other kinds of sleep; it’s that important. However, if you are chemically impaired from getting healthy REM sleep, there’s not much your brain can do to save you from the effects of REM sleep loss.

See: Cannabis, Cannabinoids, and Sleep: a Review of the Literature

This is, by the way, a reason that THC gets prescribed for some sleep disorders, in cases where the initial sleep disruption was because of nightmares, as it will reduce those (along with any other dreams, as collateral damage):

One thing to be careful of if using THC as a sleep aid is that withdrawal may make your symptoms worse than they were to start with:

Updates in the use of cannabis for insomnia

With all that in mind, you might consider (if you haven’t already tried it) seeing whether CBD alone improves your sleep, as while it does also extend time in deep sleep, it doesn’t reduce REM nearly as much as THC does:

👆 this study was paid for by the brand being tested, so do be aware of potential publication bias. That’s not to say the study is necessarily corrupt, and indeed it probably wasn’t, but rather, the publication of the results was dependent on the company paying for them (so hypothetically they could have pulled funding from any number of other research groups that didn’t get the results they wanted, leaving this one to be the only one published). That being said, the study is interesting, which is why we’ve linked it, and it’s a good jumping-off-point for finding a lot of related papers, which you can see listed beneath it.

CBD also has other benefits of its own, even without THC:

CBD Oil: What Does The Science Say?

Take care!

Don’t Forget…

Did you arrive here from our newsletter? Don’t forget to return to the email to continue learning!

Learn to Age Gracefully

Join the 98k+ American women taking control of their health & aging with our 100% free (and fun!) daily emails: