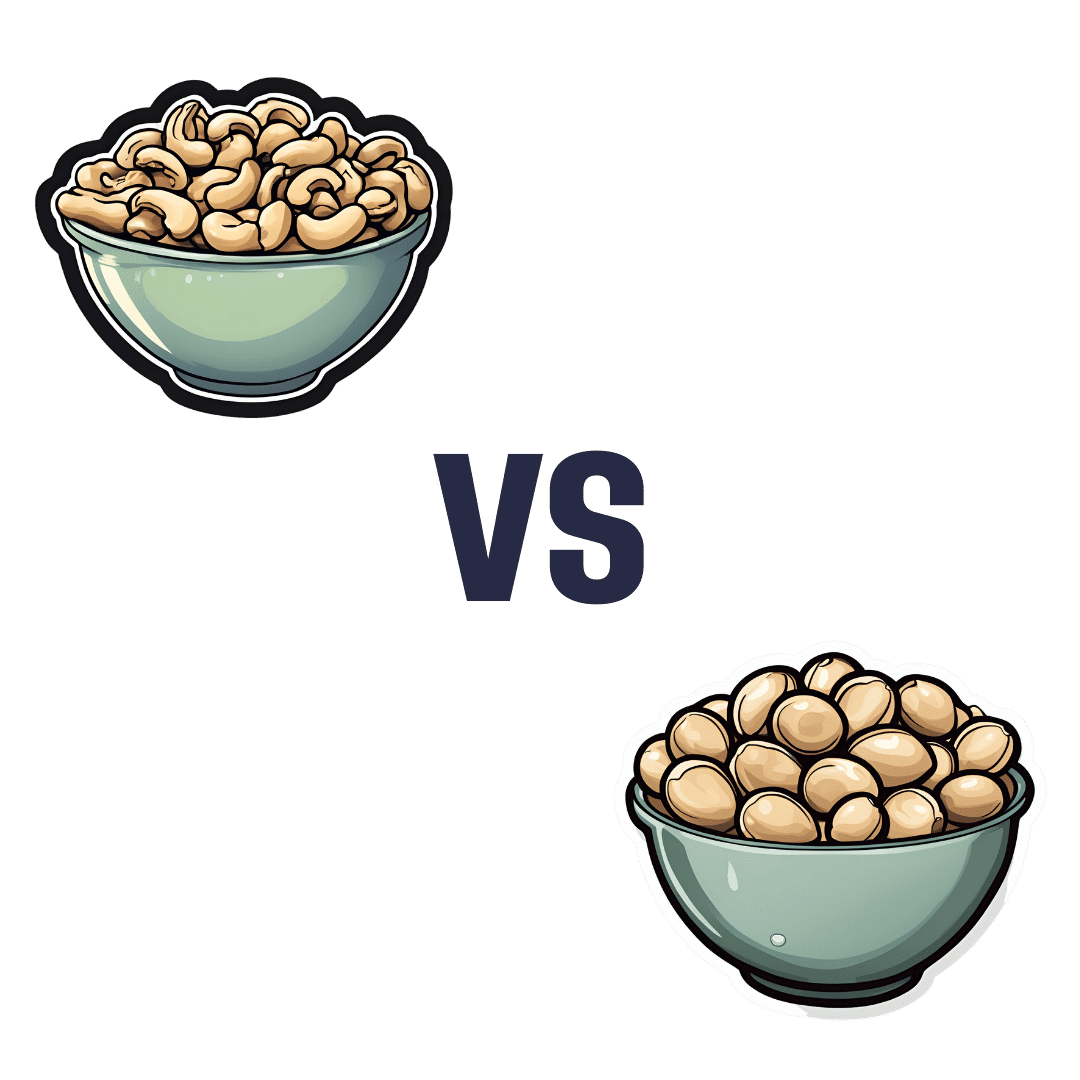

Cashew Nuts vs Macadamia Nuts – Which is Healthier?

10almonds is reader-supported. We may, at no cost to you, receive a portion of sales if you purchase a product through a link in this article.

Our Verdict

When comparing cashews to macadamias, we picked the cashews.

Why?

In terms of macros, cashews have more than 2x the protein, while macadamias have nearly 2x the fat. The fats are mostly monounsaturated, so it’s still healthy in moderation, but still, we’re going to prize the protein over it and call this category a nominal win for cashews.

When it comes to vitamins, things are fairly even; cashews have more of vitamins B5, B6, B9, and E, while macadamias have more of vitamins B1, B2, B3, and C.

In the category of minerals, cashews take the clear lead; cashews have more copper, iron, magnesium, phosphorus, potassium, selenium, and zinc, while macadamias have more calcium and manganese.

In short, enjoy both (as macadamias have their benefits too), but cashews win in total nutrient density.

Want to learn more?

You might like to read:

Why You Should Diversify Your Nuts

Take care!

Don’t Forget…

Did you arrive here from our newsletter? Don’t forget to return to the email to continue learning!

Recommended

Learn to Age Gracefully

Join the 98k+ American women taking control of their health & aging with our 100% free (and fun!) daily emails:

-

Food for Life – by Dr. Tim Spector

10almonds is reader-supported. We may, at no cost to you, receive a portion of sales if you purchase a product through a link in this article.

This book is, as the author puts it, “an eater’s guide to food and nutrition”. Rather than telling us what to eat or not eat, he provides an overview of what the latest science has to say about various foods, and leaves us to make our own informed decisions.

He also stands firmly by the “personalized nutrition” idea that he introduced in his previous book which we reviewed the other day, and gives advice on what tests we might like to perform.

The writing style is accessible, without shying away from reference to hard science. Dr. Spector provides lots of information about key chemicals, genes, gut bacteria, and more—as well as simply providing a very enjoyable read along the way.

Bottom line: if you’d like a much better idea of what food is (and isn’t) doing what, this book is an invaluable resource.

Click here to check out Food for Life, and make the best decisions for you!

Share This Post

-

Super Joints – by Pavel Tsatsouline

10almonds is reader-supported. We may, at no cost to you, receive a portion of sales if you purchase a product through a link in this article.

For those of us for whom mobility and pain-free movement are top priorities, this book has us covered. So what’s different here, compared to your average stretching book?

It’s about functional strength with the stretches. The author’s background as a special forces soldier means that his interest was not in doing arcane yoga positions so much as being able to change direction quickly without losing speed or balance, get thrown down and get back up without injury, twist suddenly without unpleasantly wrenching anything (of one’s own, at least), and generally be able to take knocks without taking damage.

While we are hopefully not having to deal with such violence in our everyday lives, the robustness of body that results from these exercises is one that certainly can go a long way to keep us injury-free.

The exercises themselves are well-described, clearly and succinctly, with equally clear illustrations.

Note: the paperback version is currently expensive, probably due to supply and demand, but if you select the Kindle version, it’s much cheaper with no loss of quality (because the illustrations are black-on-white line-drawings and very clear; perfect for Kindle e-ink)

The style of the book is very casual and conversational, yet somehow doesn’t let that distract it from being incredibly information dense; there is no fluff here, just valuable guidance.

Bottom line: if you would like to be more robust with non-nonsense exercises, then this book is a fine choice.

Click here to check out Super Joints, and make yours flexible and strong!

Share This Post

-

Why You Can’t Skimp On Amino Acids

10almonds is reader-supported. We may, at no cost to you, receive a portion of sales if you purchase a product through a link in this article.

Our body requires 20 amino acids (the building blocks of protein), 9 of which it can’t synthesize (thus called: “essential”) and absolutely must get from food. Normally, we get these amino acids from protein in our diet, and we can also supplement them by taking amino acid supplements if we wish.

Specifically, we require (per kg of bodyweight) a daily average of:

- Histidine: 10 mg

- Isoleucine: 20 mg

- Leucine: 39 mg

- Lysine: 30 mg

- Methionine: 10.4 mg

- Phenylalanine*: 25 mg

- Threonine: 15 mg

- Tryptophan: 4 mg

- Valine: 26 mg

*combined with the non-essential amino acid tyrosine

Source: Protein and Amino Acid Requirements In Human Nutrition: WHO Technical Report

Why this matters

A lot of attention is given to protein, and making sure we get enough of it, especially as we get older, because the risk of sarcopenia (muscle mass loss) increases with age:

However, not every protein comes with a complete set of essential amino acids, and/or have only trace amounts of of some amino acids, meaning that a dietary deficiency can arrive if one’s diet is too restrictive.

And, if we become deficient in even just one amino acid, then bad things start to happen quite soon. We only have so much space, so we’re going to oversimplify here, but:

- Histidine: is needed to produce histamine (vital for immune responses, amongst other things), and is also important for maintaining the myelin sheaths on nerve cells.

- Isoleucine: is very involved in muscle metabolism and makes up the bulk of muscle tissue.

- Leucine: is critical for muscle synthesis and repair, as well as wound healing in general, and blood sugar regulation.

- Lysine: is also critical in muscle synthesis, as well as calcium absorption and hormone production, as well as making collagen.

- Methionine: is very important for energy metabolism, zinc absorption, and detoxification.

- Phenylalanine: is a necessary building block of a lot of neurotransmitters, as well as being a building block of some amino acids not listed here (i.e., the ones your body synthesizes, but can’t without phenylalanine).

- Threonine: is mostly about collagen and elastin production, and is also very important for your joints, as well as fat metabolism.

- Tryptophan: is the body’s primary precursor to serotonin, so good luck making the latter without the former.

- Valine: is mostly about muscle growth and regeneration.

So there you see, the ill effects of deficiency can range from “muscle atrophy” to “brain stops working” and “bones fall apart” and more. In short, any essential amino acid deficiency not remedied will ultimately result in death; we literally become non-viable as organisms without these 9 things.

What to do about it (the “life hack” part)

Firstly, if you eat a lot of animal products, those are “complete” proteins, meaning that they contain all 9 essential amino acids in sensible quantities. The reason that all animal products have these, is because they are just as essential for the other animals as they are for us, so they, just like us, must consume (and thus contain) them.

However, a lot of animal products come with other health risks:

Do We Need Animal Products To Be Healthy? ← this covers which animal products are definitely very health-risky, and which are probably fine according to current best science

…so many people may prefer to get more (or possibly all) dietary protein from plants.

However, plants, unlike us, do not need to consume all 9 essential amino acids, and this may or may not contain them all.

Soy is famously a “complete” protein insofar as it has all the amino acids we need.

But what if you’re allergic to soy?

Good news! Peas are also a “complete” protein and will do the job just fine. They’re also usually cheaper.

Final note

An oft-forgotten thing is that some other amino acids are “conditionally essential”, meaning that while we can technically synthesize them, sometimes we can’t synthesize enough and must get them from our diet.

The conditions that trigger this “conditionally essential” status are usually such things as fighting a serious illness, recovering from a serious injury, or pregnancy—basically, things where your body has to work at 110% efficiency if it wants to get through it in one piece, and that extra 10% has to come from somewhere outside the body.

Examples of commonly conditionally essential amino acids are arginine and glycine.

Arginine is critical for a lot of cell-signalling processes as well as mitochondrial function, as well as being a precursor to other amino acids, including creatine.

As for glycine?

Check out: The Sweet Truth About Glycine

Enjoy!

Share This Post

Related Posts

-

Health Shots − by Toby Amidor

10almonds is reader-supported. We may, at no cost to you, receive a portion of sales if you purchase a product through a link in this article.

First a quick note on qualifications: while not a doctor, she’s a RD, CDN, FAND, and as such, this is a very nutrition-focused book.

As a general rule of thumb, juices are unhealthy because of being largely liquid sugar and no fiber, but in this case:

- even the juice-based tonics are very small portions, so even if some have a high glycemic index, they’ll still have a low glycemic load, which means that having one is unlikely to spike blood glucose and thus insulin

- many of the tonics have fiber in any case, due to how they are made.

The tonics are divided into sections per what one wants to focus on, e.g. anti-inflammatory, brain health, sleep, gut health, skin/nails/hair, etc.

That said, some of the recipes are a little optimistic about how much effect the dosage present will have. For example, we calculate an an average of 0.03mg of resveratrol in her grape-based shot boasting resveratrol benefits. For contrast, resveratrol supplements range from 500mg to 200mg. So, to get the equivalent of the least generous supplement, you’d need to drink 16,667 shots.

Bottom line: some of the the health claims in this book are overstated, but by and large, it’s hard to go wrong consuming more plants, and these “health shots” are not a bad way to get a good dose of phytonutrients without hitting glycemic problems.

Don’t Forget…

Did you arrive here from our newsletter? Don’t forget to return to the email to continue learning!

Learn to Age Gracefully

Join the 98k+ American women taking control of their health & aging with our 100% free (and fun!) daily emails:

-

Cheeky diet soft drink getting you through the work day? Here’s what that may mean for your health

10almonds is reader-supported. We may, at no cost to you, receive a portion of sales if you purchase a product through a link in this article.

Many people are drinking less sugary soft drink than in the past. This is a great win for public health, given the recognised risks of diets high in sugar-sweetened drinks.

But over time, intake of diet soft drinks has grown. In fact, it’s so high that these products are now regularly detected in wastewater.

So what does the research say about how your health is affected in the long term if you drink them often?

Breakingpic/Pexels What makes diet soft drinks sweet?

The World Health Organization (WHO) advises people “reduce their daily intake of free sugars to less than 10% of their total energy intake. A further reduction to below 5% or roughly 25 grams (six teaspoons) per day would provide additional health benefits.”

But most regular soft drinks contain a lot of sugar. A regular 335 millilitre can of original Coca-Cola contains at least seven teaspoons of added sugar.

Diet soft drinks are designed to taste similar to regular soft drinks but without the sugar. Instead of sugar, diet soft drinks contain artificial or natural sweeteners. The artificial sweeteners include aspartame, saccharin and sucralose. The natural sweeteners include stevia and monk fruit extract, which come from plant sources.

Many artificial sweeteners are much sweeter than sugar so less is needed to provide the same burst of sweetness.

Diet soft drinks are marketed as healthier alternatives to regular soft drinks, particularly for people who want to reduce their sugar intake or manage their weight.

But while surveys of Australian adults and adolescents show most people understand the benefits of reducing their sugar intake, they often aren’t as aware about how diet drinks may affect health more broadly.

Diet soft drinks contain artificial or natural sweeteners. Vintage Tone/Shutterstock What does the research say about aspartame?

The artificial sweeteners in soft drinks are considered safe for consumption by food authorities, including in the US and Australia. However, some researchers have raised concern about the long-term risks of consumption.

People who drink diet soft drinks regularly and often are more likely to develop certain metabolic conditions (such as diabetes and heart disease) than those who don’t drink diet soft drinks.

The link was found even after accounting for other dietary and lifestyle factors (such as physical activity).

In 2023, the WHO announced reports had found aspartame – the main sweetener used in diet soft drinks – was “possibly carcinogenic to humans” (carcinogenic means cancer-causing).

Importantly though, the report noted there is not enough current scientific evidence to be truly confident aspartame may increase the risk of cancer and emphasised it’s safe to consume occasionally.

Will diet soft drinks help manage weight?

Despite the word “diet” in the name, diet soft drinks are not strongly linked with weight management.

In 2022, the WHO conducted a systematic review (where researchers look at all available evidence on a topic) on whether the use of artificial sweeteners is beneficial for weight management.

Overall, the randomised controlled trials they looked at suggested slightly more weight loss in people who used artificial sweeteners.

But the observational studies (where no intervention occurs and participants are monitored over time) found people who consume high amounts of artificial sweeteners tended to have an increased risk of higher body mass index and a 76% increased likelihood of having obesity.

In other words, artificial sweeteners may not directly help manage weight over the long term. This resulted in the WHO advising artificial sweeteners should not be used to manage weight.

Studies in animals have suggested consuming high levels of artificial sweeteners can signal to the brain it is being starved of fuel, which can lead to more eating. However, the evidence for this happening in humans is still unproven.

You can’t go wrong with water. hurricanehank/Shutterstock What about inflammation and dental issues?

There is some early evidence artificial sweeteners may irritate the lining of the digestive system, causing inflammation and increasing the likelihood of diarrhoea, constipation, bloating and other symptoms often associated with irritable bowel syndrome. However, this study noted more research is needed.

High amounts of diet soft drinks have also been linked with liver disease, which is based on inflammation.

The consumption of diet soft drinks is also associated with dental erosion.

Many soft drinks contain phosphoric and citric acid, which can damage your tooth enamel and contribute to dental erosion.

Moderation is key

As with many aspects of nutrition, moderation is key with diet soft drinks.

Drinking diet soft drinks occasionally is unlikely to harm your health, but frequent or excessive intake may increase health risks in the longer term.

Plain water, infused water, sparkling water, herbal teas or milks remain the best options for hydration.

Lauren Ball, Professor of Community Health and Wellbeing, The University of Queensland and Emily Burch, Accredited Practising Dietitian and Lecturer, Southern Cross University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Don’t Forget…

Did you arrive here from our newsletter? Don’t forget to return to the email to continue learning!

Learn to Age Gracefully

Join the 98k+ American women taking control of their health & aging with our 100% free (and fun!) daily emails:

-

This Week In Brain News

10almonds is reader-supported. We may, at no cost to you, receive a portion of sales if you purchase a product through a link in this article.

While reading this week’s health news, we’ve singled out three brain-related articles to feature here:

Bad breath now, bad brain later?

Researchers found links between oral microbiome populations, and changes in brain function with aging. The short version is indeed “bad breath now = bad brain later”, but more specifically:

- People who had large numbers of the bacteria groups Neisseria and Haemophilus had better memory, attention and ability to do complex tasks

- People who had higher levels of Porphyromonas had more memory problems later

- People with a lot of Prevotella tended to predict poorer brain health and was more common in people who carry the Alzheimer’s Disease risk gene, APOE4.

If you’ve never heard of half of those, don’t worry: mostly your oral microbiome can take care of itself, provide you consistently do the things that create a “good” oral microbiome. So, see our “related” link below:

Read in full: Mouth bacteria may hold insight into your future brain function

Related: Improve Your Oral Microbiome

Weeding out a major cause of cognitive decline

Cannabis may be great for relaxation, but regular use is not great for mental sharpness, and recent use (even if not regular, and even if currently sober) shows a similar dip in cognitive abilities, especially working memory. In other words, cannabis use for relaxation should be at most an occasional thing, rather than an everyday thing.

While the results of the study are probably not shocking, something that we found interesting was their classification system:

❝Heavy users are considered young adults who’ve used cannabis more than 1000 times over their lifetime. Whereas, using 10 to 999 times was considered a moderate user, and fewer than 10 times was considered a non-user.❞

Which—while being descriptive rather than prescriptive in nature—suggests that, to be on the healthy end of the bell curve, an occasional cannabis-user might want to consider “if you have 999 uses before you hit the “heavy user” category, project those 999 uses against your life expectancy, and moderate your use accordingly”. In other words, a person just now starting use, who expects to live another 40 years, would calculate: 999/40 = 24.9 uses per year, so call it 2 per month. A person who only expects to live another 20 years, would do the same math and arrive at 4 per month.

Disclaimer: the above is intended as an interesting reframe, and a way of looking at long-term cannabis use while being mindful of the risks. It is not intended as advice. This health-conscious writer personally has no intention of using at all, unless perhaps in some bad future scenario in which I have bad chronic pain, I might consider that pain relief effects may be worth the downsides. Or I might not; I hope not to be in the situation to find out!

Read in full: Largest study ever done on cannabis and brain function finds impact on working memory

Related: Cannabis Myths vs Reality

Mind-reading technology improves again

We’ve come quite a way from simple 1/0 reads, and basic cursor control! Now, researchers have created a brain decode that can translate a person’s thoughts into continuous text, without requiring the person to focus on words—in other words, it verbalizes the ideas directly. Most recently, the latest upgrade means that while previously, the device had to be trained on an individual brain for many hours, now the training/calibration process takes only an hour:

Read in full: Improved brain decoder holds promise for communication in people with aphasia

Related: Are Brain Chips Safe?

Take care!

Don’t Forget…

Did you arrive here from our newsletter? Don’t forget to return to the email to continue learning!

Learn to Age Gracefully

Join the 98k+ American women taking control of their health & aging with our 100% free (and fun!) daily emails: