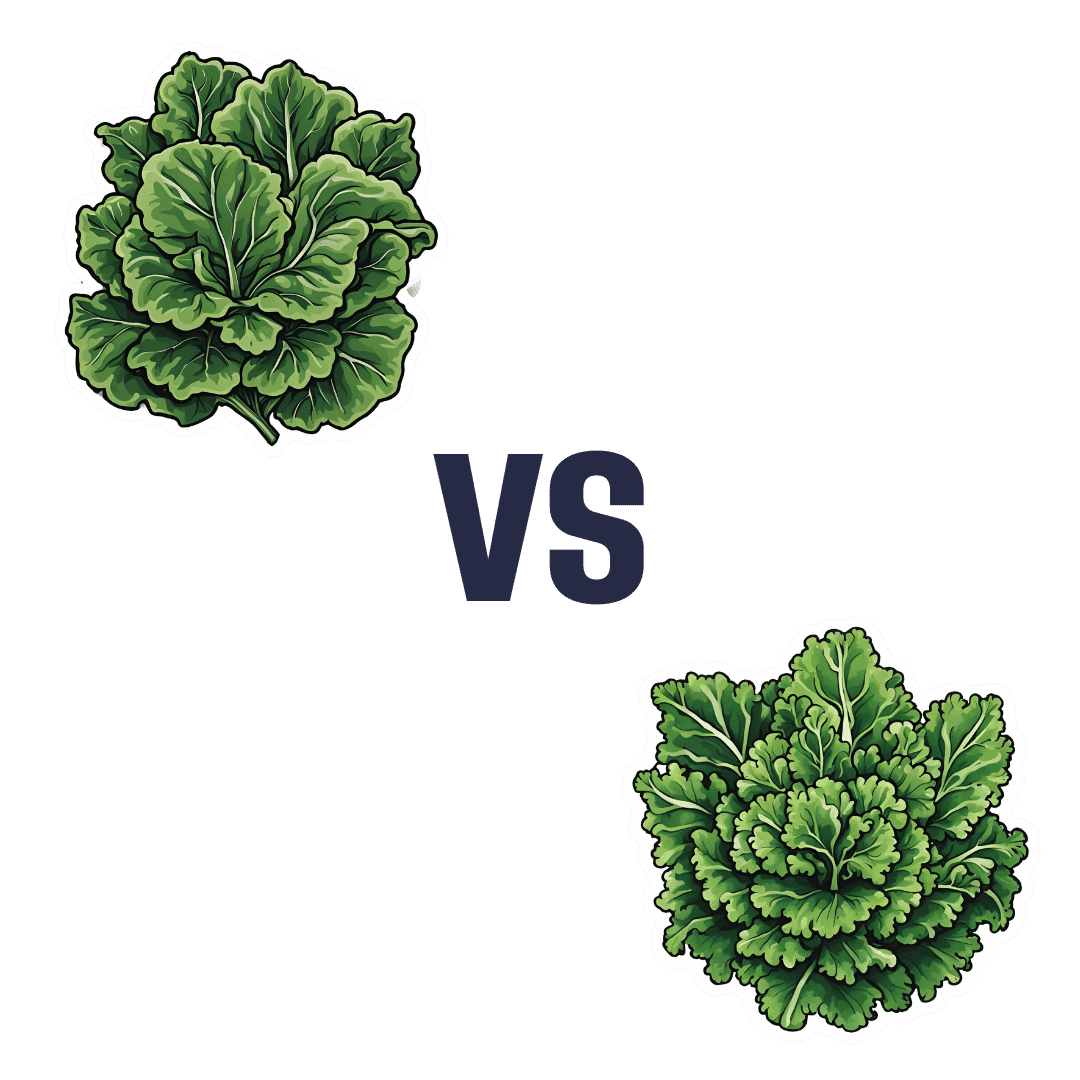

Collard Greens vs Kale – Which is Healthier?

10almonds is reader-supported. We may, at no cost to you, receive a portion of sales if you purchase a product through a link in this article.

Our Verdict

When comparing collard greens to kale, we picked the collard greens.

Why?

Once again we have Brassica oleracea vs Brassica oleracea, (the same species that is also broccoli, cauliflower, Brussels sprouts, various kinds of cabbage, and more) and once again there are nutritional differences between the two cultivars:

In terms of macros, collard greens have more protein, equal carbs, and 2x the fiber. So that’s a win for collard greens.

In the category of vitamins, collard greens have more of vitamins B2, B3, B5, B9, E, and choline, while kale has more of vitamins A, B1, B6, C, and K. Nominally a 6:5 win for collard greens, though it’s worth noting that while most of the margins of difference are about the same, collard greens have more than 10x the choline, too.

When it comes to minerals, collard greens have more calcium, iron, magnesium, manganese, and phosphorus, while kale has more copper, potassium, selenium, and zinc. A genuinely marginal 5:4 win for collard greens this time.

All in all, a clear win for collard greens over the (otherwise rightly) established superfood kale. Collard greens just don’t get enough appreciation in comparison!

Want to learn more?

You might like to read:

What’s Your Plant Diversity Score? ← another reason it’s good to mix things up rather than just using the same ingredients out of habit!

Take care!

Don’t Forget…

Did you arrive here from our newsletter? Don’t forget to return to the email to continue learning!

Recommended

Learn to Age Gracefully

Join the 98k+ American women taking control of their health & aging with our 100% free (and fun!) daily emails:

-

Why is toddler milk so popular? Follow the money

10almonds is reader-supported. We may, at no cost to you, receive a portion of sales if you purchase a product through a link in this article.

Toddler milk is popular and becoming more so. Just over a third of Australian toddlers drink it. Parents spend hundreds of millions of dollars on it globally. Around the world, toddler milk makes up nearly half of total formula milk sales, with a 200% growth since 2005. Growth is expected to continue.

We’re concerned about the growing popularity of toddler milk – about its nutritional content, cost, how it’s marketed, and about the impact on the health and feeding of young children. Some of us voiced our concerns on the ABC’s 7.30 program recently.

But what’s in toddler milk? How does it compare to cow’s milk? How did it become so popular?

What is toddler milk? Is it healthy?

Toddler milk is marketed as appropriate for children aged one to three years. This ultra-processed food contains:

- skim milk powder (cow, soy or goat)

- vegetable oil

- sugars (including added sugars)

- emulsifiers (to help bind the ingredients and improve the texture)

added vitamins and minerals.

Toddler milk is usually lower in calcium and protein, and higher in sugar and calories than regular cow’s milk. Depending on the brand, a serve of toddler milk can contain as much sugar as a soft drink.

Even though toddler milks have added vitamins and minerals, these are found in and better absorbed from regular foods and breastmilk. Toddlers do not need the level of nutrients found in these products if they are eating a varied diet.

Global health authorities, including the World Health Organization (WHO), and Australia’s National Health and Medical Research Council, do not recommend toddler milk for healthy toddlers.

Some children with specific metabolic or dietary medical problems might need tailored alternatives to cow’s milk. However, these products generally are not toddler milks and would be a specific product prescribed by a health-care provider.

Toddler milk is also up to four to five times more expensive than regular cow’s milk. “Premium” toddler milk (the same product, with higher levels of vitamins and minerals) is more expensive.

With the cost-of-living crisis, this means families might choose to go without other essentials to afford toddler milk.

Toddler milk is more expensive than cow’s milk and contains more sugar.

Dragana Gordic/ShutterstockHow toddler milk was invented

Toddler milk was created so infant formula companies could get around rules preventing them from advertising their infant formula.

When manufacturers claim benefits of their toddler milk, many parents assume these claimed benefits apply to infant formula (known as cross-promotion). In other words, marketing toddler milks also boosts interest in their infant formula.

Manufacturers also create brand loyalty and recognition by making the labels of their toddler milk look similar to their infant formula. For parents who used infant formula, toddler milk is positioned as the next stage in feeding.

How toddler milk became so popular

Toddler milk is heavily marketed. Parents are told toddler milk is healthy and provides extra nutrition. Marketing tells parents it will benefit their child’s growth and development, their brain function and their immune system.

Toddler milk is also presented as a solution to fussy eating, which is common in toddlers.

However, regularly drinking toddler milk could increase the risk of fussiness as it reduces opportunities for toddlers to try new foods. It’s also sweet, needs no chewing, and essentially displaces energy and nutrients that whole foods provide.

Toddler milk is said to help fussy eating, but it may make things worse.

zlikovec/ShutterstockGrowing concern

The WHO, along with public health academics, has been raising concerns about the marketing of toddler milk for years.

In Australia, moves to curb how toddler milk is promoted have gone nowhere. Toddler milk is in a category of foods that are allowed to be fortified (to have vitamins and minerals added), with no marketing restrictions. The Australian Competition & Consumer Commission also has concerns about the rise of toddler milk marketing. Despite this, there is no change in how it’s regulated.

This is in contrast to voluntary marketing restrictions in Australia for infant formula.

What needs to happen?

There is enough evidence to show the marketing of commercial milk formula, including toddler milk, influences parents and undermines child health.

So governments need to act to protect parents from this marketing, and to put child health over profits.

Public health authorities and advocates, including us, are calling for the restriction of marketing (not selling) of all formula products for infants and toddlers from birth through to age three years.

Ideally, this would be mandatory, government-enforced marketing restrictions as opposed to industry self-regulation in place currently for infant formulas.

We musn’t blame parents

Toddlers are eating more processed foods (including toddler milk) than ever because time-poor parents are seeking a convenient option to ensure their child is getting adequate nutrition.

Formula manufacturers have used this information, and created a demand for an unnecessary product.

Parents want to do the best for their toddlers, but they need to know the marketing behind toddler milks is misleading.

Toddler milk is an unnecessary, unhealthy, expensive product. Toddlers just need whole foods and breastmilk, and/or cow’s milk or a non-dairy, milk alternative.

If parents are worried about their child’s eating, they should see a health-care professional.

Anthea Rhodes, a paediatrician from Royal Children’s Hospital Melbourne and a lecturer at the University of Melbourne, co-authored this article.

Jennifer McCann, Lecturer Nutrition Sciences, Institute for Physical Activity and Nutrition, Deakin University; Karleen Gribble, Adjunct Associate Professor, School of Nursing and Midwifery, Western Sydney University, and Naomi Hull, PhD candidate, University of Sydney

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Share This Post

-

Cranberries vs Goji Berries – Which is Healthier?

10almonds is reader-supported. We may, at no cost to you, receive a portion of sales if you purchase a product through a link in this article.

Our Verdict

When comparing cranberries to goji berries, we picked the cranberries.

Why?

Both are great! And your priorities may differ. Here’s how they stack up:

In terms of macros, goji berries have more protein, carbs, and fiber. This is consistent with them generally being eaten very dried, whereas cranberries are more often eaten fresh or from frozen, or partially rehydrated. In any case, goji berries are the “more food per food” option, so it wins this category. The glycemic indices are both low, by the way, though goji berries are the lower.

When it comes to vitamins, cranberries have more of vitamins B1, B2, B3, B5, B6, B9, E, K, and choline, while goji berries have more of vitamins A and C. Admittedly it’s a lot more, but still, on strength of overall vitamin coverage, the clear winner here is cranberries.

We see a similar story when it comes to minerals: cranberries have more copper, magnesium, manganese, phosphorus, potassium, selenium, and zinc, while goji berries have (a lot) more calcium and iron. Again, by strength of overall mineral coverage, the clear winner here is cranberries.

Cranberries do also have some extra phytochemical benefits, including their prevention/cure status when it comes to UTIs—see our link below for more on that.

At any rate, enjoy either or both, but those are the strengths and weaknesses of these two berries!

Want to learn more?

You might like to read:

- Health Benefits Of Cranberries (But: You’d Better Watch Out)

- Goji Berries: Which Benefits Do They Really Have?

- The Sugary Food That Lowers Blood Sugars ← this is also about goji berries

Take care!

Share This Post

-

The Fruit That Can Specifically Reduce Belly Fat

10almonds is reader-supported. We may, at no cost to you, receive a portion of sales if you purchase a product through a link in this article.

Gambooge: Game-Changer Or Gamble?

The gambooge, also called the gummi-gutta, whence its botanical name Garcinia gummi-gutta (formerly Gardinia cambogia), is also known as the Malabar tamarind, and it even got an English name, the brindle berry.

It’s a fruit that looks like a small pale yellow pumpkin in shape, but it grows on trees and has a taste so sour, that it’s usually used only in cooking, and not eaten raw

which makes this writer really want to try it raw now.Its active phytochemical compound hydroxycitric acid (HCA) rose to popularity as a supplement in the US based on a paid recommendation from Dr. Oz, and then became a controversy as supplements associated with it, were in turn associated with hepatotoxicity (more on this in the “Is it safe?” section below).

What do people use it for?

Simply put: it’s a weight loss supplement.

Less simply put: least interestingly, it’s a mild appetite suppressant:

Safety and mechanism of appetite suppression by a novel hydroxycitric acid extract (HCA-SX) ← this talks more about the biochemistry, but isn’t a human study. Human studies have been small and with mixed results. It seems likely that (as in the rat studies discussed above) the mechanism of action is largely about increasing serotonin, which itself is a well-established appetite suppressant. Therefore, the results will depend somewhat on a person’s brain’s serotonergic system.

We’ll revisit that later, but first let’s look at…

Even less simply put: its other mechanism of action is much more interesting; it actually blocks the production of fat (especially: visceral fat) in the body, by inhibiting citrate lyase, which enzyme plays a significant role in fat production:

Effects of (−)-hydroxycitrate on net fat synthesis as de novo lipogenesis

More illustratively, here’s another study, which found:

❝G cambogia reduced abdominal fat accumulation in subjects, regardless of sex, who had the visceral fat accumulation type of obesity. No rebound effect was observed.

It is therefore expected that G cambogia may be useful for the prevention and reduction of accumulation of visceral fat. ❞

~ Dr. Norihiro Shigematsu et al.

As to why this is particularly important, and far more important than mere fat loss in general, see our previous main feature:

Visceral Belly Fat (And How To Lose It)

Is it safe?

It has shown a good safety profile up to large doses (2.8g/day):

Evaluation of the safety and efficacy of hydroxycitric acid or Garcinia cambogia extracts in humans

There have been some fears about hepatotoxicity, but they appear to be unfounded, and based on products that did not, in fact, contain HCA (and were merely sold by a company that used a similar name in their marketing):

No evidence demonstrating hepatotoxicity associated with hydroxycitric acid

However, as it has a serotoninergic effect, it could cause problems for anyone at risk of serotonin syndrome, which means caution is advisable if you are taking SSRIs (which reduce the rate at which the brain can scrub serotonin, with the usually laudable goal of having more serotonin in the brain—but it is possible to have too much of a good thing, and serotonin syndrome isn’t fun).

As ever, do check with your pharmacist and/or doctor, to be sure, since they can advise with regard to your specific situation and any medications you may be taking.

Want to try some?

We don’t sell it, but here for your convenience is an example product on Amazon

Enjoy!

Share This Post

Related Posts

-

Omega-3 Mushroom Spaghetti

10almonds is reader-supported. We may, at no cost to you, receive a portion of sales if you purchase a product through a link in this article.

The omega-3 is not the only healthy fat in here; we’re also going to have medium-chain triglycerides, as well as monounsaturates. Add in the ergothioneine from the mushrooms and a stack of polyphenols from, well, most of the ingredients, not to mention the fiber, and this comes together as a very healthy dish. There’s also about 64g protein in the entire recipe, so you do the math for how much that is per serving, depending on how big you want the servings to be.

You will need

- 1lb wholewheat spaghetti (or gluten-free equivalent, such as a legume-based pasta, if avoiding gluten/wheat)

- 12oz mushrooms, sliced (any non-poisonous edible variety)

- ½ cup coconut milk

- ½ onion, finely chopped

- ¼ cup chia seeds

- ¼ bulb garlic, minced (or more, if you like)

- 2 tbsp extra virgin olive oil

- 1 tbsp black pepper, coarse ground

- 1 tbsp lime juice

Method

(we suggest you read everything at least once before doing anything)

1) Cook the spaghetti according to packet instructions, or your own good sense, aiming for al dente. When it’s done, drain it, and lastly rinse it (with cold water), and set it aside.

2) Heat the olive oil in a skillet and add the onion, cooking for 5 minutes

3) Add the garlic, mushrooms, and black pepper, cooking for another 8 minutes.

4) Add the coconut milk, lime juice, and chia seeds, stirring well and cooking for a further two minutes

5) Reheat the spaghetti by passing boiling water through it in a colander (the time it spent cold was good for it; it lowered the glycemic index)

6) Serve, adding the mushroom sauce to the spaghetti:

Enjoy!

Want to learn more?

For those interested in some of the science of what we have going on today:

- The Magic of Mushrooms: “The Longevity Vitamin” (That’s Not A Vitamin)

- The Many Health Benefits of Garlic

- Black Pepper’s Impressive Anti-Cancer Arsenal (And More)

- If You’re Not Taking Chia, You’re Missing Out

Take care!

Don’t Forget…

Did you arrive here from our newsletter? Don’t forget to return to the email to continue learning!

Learn to Age Gracefully

Join the 98k+ American women taking control of their health & aging with our 100% free (and fun!) daily emails:

-

Stretching to Stay Young – by Jessica Matthews

10almonds is reader-supported. We may, at no cost to you, receive a portion of sales if you purchase a product through a link in this article.

A lot of stretching gurus (especially the Instagrammable kind) offer advices like “if you can’t do the splits balanced between two chairs to start with, that’s fine… just practise by doing the splits against a wall first!”

Jessica Matthews, meanwhile, takes a more grounded approach. A lot of this is less like yoga and more like physiotherapy—it’s uncomplicated and functional. There’s nothing flashy here… just the promise of being able to thrive in your body; supple and comfortable, doing the activities that matter to you.

On which note: the book gives advices about stretches for before and after common activities, for example:

- a bedtime routine set

- a pre-gardening set

- a post-phonecall set

- a level-up-your golf set

- a get ready for dancing set

…and many more. Whether “your thing” is cross-country skiing or knitting, she’s got you covered.

The book covers the whole body from head to toe. Whether you want to be sure to stretch everything, or just work on a particular part of your body that needs special attention, it’s there… with beautifully clear illustrations (the front cover illustration is indicative of the style—note how the muscle being stretched is highlighted in orange, too) and simple, easy-to-understand instructions.

All in all, we’re none of us getting any younger, but we sure can take some of our youth into whatever years come next. This is the stuff that life is made of!

Get your copy of “Stretching To Stay Young” from Amazon today!

Don’t Forget…

Did you arrive here from our newsletter? Don’t forget to return to the email to continue learning!

Learn to Age Gracefully

Join the 98k+ American women taking control of their health & aging with our 100% free (and fun!) daily emails:

-

The Dirt Cure – by Dr. Maya Shetreat-Klein

10almonds is reader-supported. We may, at no cost to you, receive a portion of sales if you purchase a product through a link in this article.

As we discussed in our article “Stop Sabotaging Your Gut”, there is indeed merit to living a little dirty, in particular when it comes to what we put in our mouths. Having the space of an entire book rather than a small article, Dr. Shetreat-Klein expands on this in great detail.

The subtitle mentions “growing healthy kids with food straight from the soil”; it’s worth noting that all the information here (with the exception of concerning breastfeeding etc) is equally applicable to adults too—so if it’s your own health you’re focused on rather than that of kids or grandkids, then that’s fine too.

You may be wondering: what more is there to say than “don’t scrub your vegetables as though you’re about to perform surgery with them”?

There’s a lot of background information on what things help or harm our bodies in the first place, most notably via our gut, and as an important extra consideration, the gut-brain axis. Incidentally, the author is a neurologist by professional background.

Then she gets more specific, into “include and exclude” recommendations. In this matter we have one criticism: she does recommend raw milk over pasteurized, and that is, by overwhelming scientific consensus, a terrible idea. Raw milk is an abundant source of pathogens and a breeding ground for even more. There is “living dirty” and there is “living dangerously”, and drinking raw milk is the latter. See also: Pasteurization: What It Does And Doesn’t Do

However, for the most part, the rest of her advice is sound, and there’s even a recipes section too.

The style is something of a polemic throughout, but the extensive venting does not take away from there being a lot of genuine information in here too.

Bottom line: please skip the raw milk, but aside from that, if you’d like to improve your diet to improve your gut and immune health, then this book can help with that.

Don’t Forget…

Did you arrive here from our newsletter? Don’t forget to return to the email to continue learning!

Learn to Age Gracefully

Join the 98k+ American women taking control of their health & aging with our 100% free (and fun!) daily emails: