Holistic Approach To Resculpting A Face Affected By Hypothyroidism, PCOS, Or Menopause

10almonds is reader-supported. We may, at no cost to you, receive a portion of sales if you purchase a product through a link in this article.

Mila Magnani has PCOS and hypothyroidism, but the principles are the same for menopause because both menopause and PCOS are a case of a hormone imbalance resulting in androgenic effects, so there’s a large amount of overlap.

Obviously, a portion of the difference in the thumbnail is a matter of angle and make-up, but as you can see in the video itself, there’s also a lot of genuine change underneath, too:

Stress-free method

Firstly, she bids us get lab tests and work with a knowledgeable doctor to address potential thyroid, hormonal, or nutrient imbalances. Perhaps we already know at least part of what is causing our problems, but even if so, it doesn’t hurt to take steps to rule the others out. Imagine spending ages unsuccessfully battling PCOS or menopause, only to discover it was a thyroid issue, and you were fighting the wrong battle!

Magnani used a natural route to manage her PCOS and hypothyroidism, while acknowledging that medication is fine too; it’s usually cheaper and more convenient—and there’s a lot more standardization for medications than there is for supplements, which makes it a lot easier to navigate, find what works, and keep getting the exact same thing once it does work.

Other things she recommends include:

- Lymphatic drainage: addressing the lymphatic system to reduce puffiness. Techniques include lymphatic drainage massage, stretching, rebounding (trampoline), and dry brushing. She emphasizes that for facial de-puffing, it’s important to treat the whole upper body, not just the face.

- Low-impact exercise: she switched from high-intensity workouts to low-impact exercises like nature walking and gentle stretching to reduce stress and improve health.

- Nervous system regulation: she worked on nervous system regulation by means of journaling, breathwork, and stimulating the vagus nerve, which improved sleep and reduced stress and anxiety. These things, of course, have knock-on benefits for almost every part of health.

- Diet: she adopted a low-glycemic diet, reduced salt intake, and cooked at home to avoid water retention caused by high sodium in restaurant meals.

- Natural diuretics: she uses teas like hibiscus and chamomile to reduce puffiness after consuming high-sodium foods.

- Sauna and sweating: consider a sauna mat or hot baths to detox and reduce swelling; that’s what she uses in lieu of a convenient sauna.

You may be wondering how quickly you can expect results: it took 3–6 months of daily effort to see significant changes, and she now maintains the routine less frequently (every 2–3 days, instead of daily).

For more on all this, enjoy:

Click Here If The Embedded Video Doesn’t Load Automatically!

Want to learn more?

You might also like to read:

- What Does “Balance Your Hormones” Even Mean?

- 7-Minute Face Fitness For Lymphatic Drainage & Youthful Jawline

- Saunas: Health Benefits (& Caveats)

Take care!

Don’t Forget…

Did you arrive here from our newsletter? Don’t forget to return to the email to continue learning!

Recommended

Learn to Age Gracefully

Join the 98k+ American women taking control of their health & aging with our 100% free (and fun!) daily emails:

-

Imposter Syndrome (and why almost everyone has it)

10almonds is reader-supported. We may, at no cost to you, receive a portion of sales if you purchase a product through a link in this article.

Imposter Syndrome (and why almost everyone has it)

Imposter syndrome is the pervasive idea that we’re not actually good enough, people think we are better than we are, and at any moment we’re going to get found out and disappoint everyone.

Beyond the workplace

Imposter syndrome is most associated with professionals. It can range from a medical professional who feels like they’ve been projecting an image of confidence too much, to a writer or musician who is sure that their next piece will never live up to the acclaim of previous pieces and everyone will suddenly realize they don’t know what they’re doing, to a middle-manager who feels like nobody above or below them realizes how little they know how to do.

But! Less talked-about (but no less prevalent) is imposter syndrome in other areas of life. New parents tend to feel this strongly, as can the “elders” of a family that everyone looks to for advice and strength and support. Perhaps worst is when the person most responsible for the finances of a household feels like everyone just trusts them to keep everything running smoothly, and maybe they shouldn’t because it could all come crashing down at any moment and everyone will see them for the hopeless shambles of a human being that they really are.

Feelings are not facts

And yet (while everyone makes mistakes sometimes) the reality is that we’re all doing our best. Given that imposter syndrome affects up to 82% of people, let’s remember to have some perspective. Everyone feels like they’re winging it sometimes. Everyone feels the pressure.

Well, perhaps not everyone. There’s that other 18%. Some people are sure they’re the best thing ever. Then again, there’s probably some in that 18% that actually feel worse than the 82%—they just couldn’t admit it, even in an anonymized study.

But one thing’s for sure: it’s very, very common. Especially in high-performing women, by the way, and people of color. In other words, people who typically “have to do twice as much to get recognized as half as good”.

That said, the flipside of this is that people who are not in any of those categories may feel “everything is in my favor, so I really have no excuse to not achieve the most”, and can sometimes take very extreme actions to try to avoid perceived failure, and it can be their family that pays the price.

Things to remember

If you find imposter syndrome nagging at you, remember these things:

- There are people far less competent than you, doing the same thing

- Nobody knows how to do everything themselves, especially at first

- If you don’t know how to do something, you can usually find out

- There is always someone to ask for help, or at least advice, or at least support

At the end of the day, we evolved to eat fruit and enjoy the sun. None of us are fully equipped for all the challenges of the modern world, but if we do our reasonable best, and look after each other (and that means that you too, dear reader, deserve looking after as well), we can all do ok.

Share This Post

-

Can You Reverse Gray Hair? A Dermatologist Explains

10almonds is reader-supported. We may, at no cost to you, receive a portion of sales if you purchase a product through a link in this article.

Betteridge’s Law of Headlines states “any headline that ends in a question mark can be answered by the word no“—it’s not really a universal truth, but it’s true surprisingly often, and, as board certified dermatologist “The Beauty MD” Dr. Sam Ellis explains, it’s true in this case.

But, all is not lost.

Physiological Factors

Hair color is initially determined by genes and gene expression, instructing the body to color it with melanin (brown and black) and/or pheomelanin (blonde and red). If and when the body produces less of those pigments, our hair will go gray.

Factors that affect if/when our hair will go gray include:

- Genetics: primary determinant, essentially a programmed change

- Age: related to the above, but critically, the probability of going gray in any given year increases with age

- Ethnicity: the level of melanin in our skin is an indicator of how long we are likely to maintain melanin in our hair. Black people with the darkest skintones will thus generally go gray last, whereas white people with the lightest skintones will generally go gray first, and so on for a spectrum between the two.

- Medical conditions: immune conditions such as vitiligo, thyroid disease, and pernicious anemia promote an earlier loss of pigmentation

- Stress: oxidative stress, mainly, so factors like smoking will cause earlier graying. But yes, also chronic emotional stress does lead to oxidative stress too. Interestingly, this seems to be more about norepinephrine than cortisol, though.

- Nutrient deficiencies: the body can make a lot of things, but it needs the raw ingredients. Not having the right amounts of important vitamins and minerals will result in a loss of pigmentation (amongst other more serious problems). Vitamins B6, B9, and B12 are talked about in the video, as are iron and zinc. Copper is also needed for some hair colors. Selenium is needed for good hair health in general (but not too much, as an excess of selenium paradoxically causes hair loss), and many related things will stop working properly without adequate magnesium. Hair health will also benefit a lot from plenty of vitamin B7.

So, managing the above factors (where possible; obviously some of the above aren’t things we can influence) will result in maintaining one’s hair pigment for longer. As for texture, by the way, the reason gray hair tends to have a rougher texture is not for the lack of pigment itself, but is due to decreased sebum production. Judicious use of exogenous hair oils (e.g. argan oil, coconut oil, or whatever your preference may be) is a fine way to keep your grays conditioned.

However, once your hair has gone gray, there is no definitive treatment with good evidence for reversing that, at present. Dye it if you want to, or don’t. Many people (including this writer, who has just a couple of streaks of gray herself) find gray hair gives a distinguished look, and such harmless signs of age are a privilege not everyone gets to reach, and thus may be reasonably considered a cause for celebration

For more on all of the above, enjoy:

Click Here If The Embedded Video Doesn’t Load Automatically!

Want to learn more?

You might also like to read:

Take care!

Share This Post

-

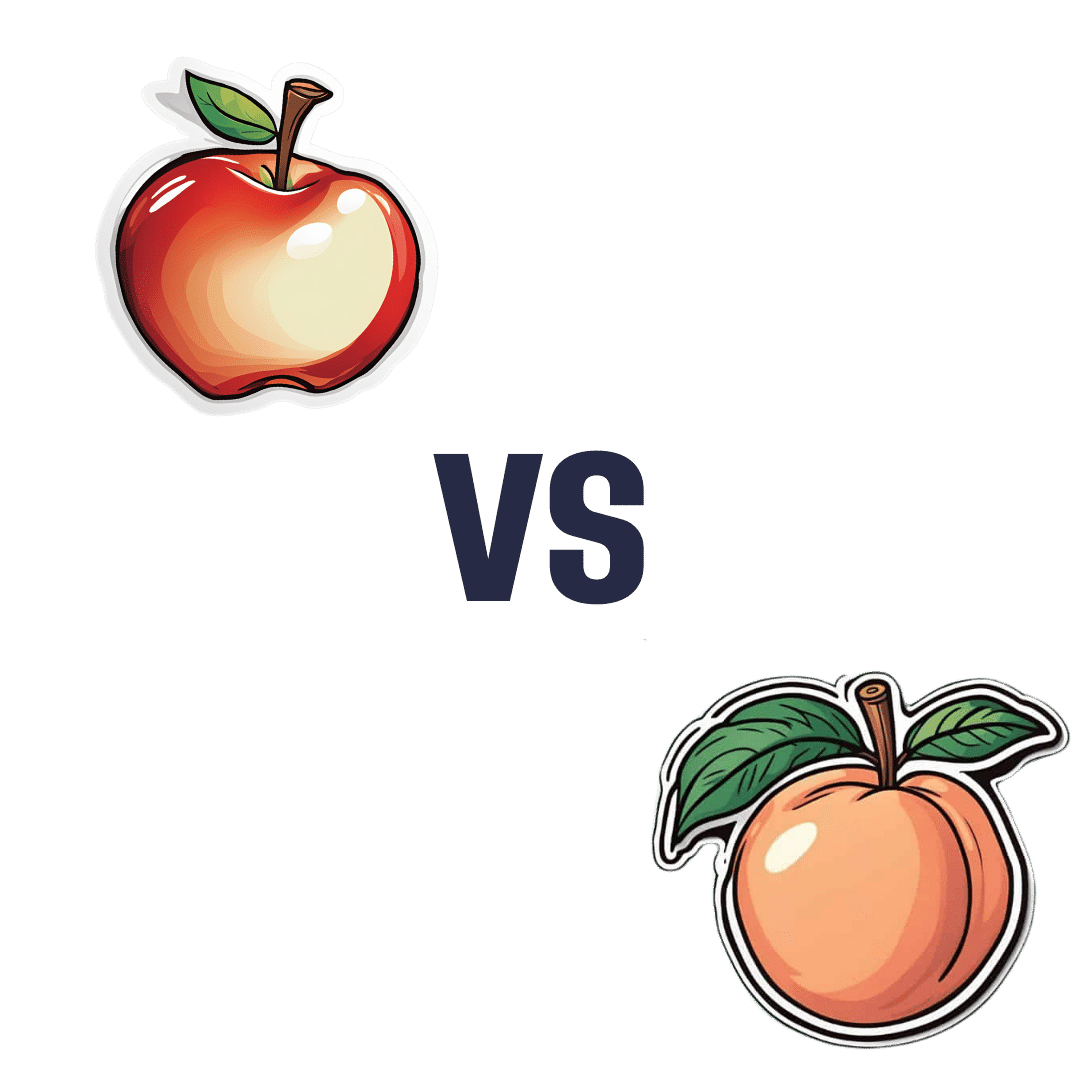

Apple vs Peach – Which is Healthier?

10almonds is reader-supported. We may, at no cost to you, receive a portion of sales if you purchase a product through a link in this article.

Our Verdict

When comparing apples to peaches, we picked the peaches.

Why?

Both have their merits, but apples can’t compete with peaches’ micronutrient profile!

In terms of macros, apples have more carbs and fiber, for a comparable glycemic index, so we give apples a marginal win in the macros category to start with.

In the category of vitamins, apples have more vitamin B6, while peaches have more of vitamins A, B1, B2, B3, B5, B7, B9, C, E, K, and choline—an easy win for peaches.

When it comes to minerals, apples are not higher in any minerals, while peaches have more calcium, copper, iron, magnesium, manganese, phosphorus, potassium, selenium, and zinc. Another clear win for peaches!

Looking at polyphenols, peaches have a higher total amount (in mg/100g) of polyphenols, as well as more variety thereof. One more win for peaches.

Adding up the sections makes for a clear win for peaches, but by all means enjoy either or both; diversity is good!

Want to learn more?

You might like:

Top 8 Fruits That Prevent & Kill Cancer ← peaches are number 2 on the list! They contain phytochemicals that induce cell death in cancer cells while sparing healthy ones 😎

Enjoy!

Share This Post

Related Posts

-

‘Active recovery’ after exercise is supposed to improve performance – but does it really work?

10almonds is reader-supported. We may, at no cost to you, receive a portion of sales if you purchase a product through a link in this article.

Imagine you have just finished a workout. Your legs are like jelly, your lungs are burning and you just want to collapse on the couch.

But instead, you pick yourself up and go for a brisk walk.

While this might seem counterintuitive, doing some light activity after an intense workout – known as “active recovery” – has been suggested to reduce soreness and speed up recovery after exercise.

But does it work or is it just another fitness myth?

gpointstudio/Shutterstock What is active recovery?

Active recovery simply describes doing some low-intensity physical activity after a strenuous bout of exercise.

This is commonly achieved through low-intensity cardio, such as walking or cycling, but can also consist of low-intensity stretching, or even bodyweight exercises such as squats and lunges.

The key thing is making sure the intensity is light or moderate, without moving into the “vigorous” range.

As a general rule, if you can maintain a conversation while you’re exercising, you are working at a light-to-moderate intensity.

Some people consider doing an easy training session on their “rest days” as a form of active recovery. However, this has not really been researched. So we will be focusing on the more traditional form of active recovery in this article, where it is performed straight after exercise.

What does active recovery do?

Active recovery helps speed up the removal of waste products, such as lactate and hydrogen, after exercise. These waste products are moved from the muscles into the blood, before being broken down and used for energy, or simply excreted.

This is thought to be one of the ways it promotes recovery.

In some instances active recovery has been shown to reduce muscle soreness in the days following exercise. This may lead to a faster return to peak performance in some physical capabilities such as jump height.

Active recovery can involve stretching. fatir29/Shutterstock But, active recovery does not appear to reduce post-exercise inflammation. While this may sound like a bad thing, it’s not.

Post-exercise inflammation can promote increases in strength and fitness after exercise. And so when it’s reduced (say, by using ice baths after exercise) this can lead to smaller training improvements than would be seen otherwise.

This means active recovery can be used regularly after exercise without the risk of affecting the benefits of the main exercise session.

There’s evidence to the contrary too

Not all research on active recovery is positive.

Several studies indicate it’s no better than simply lying on the couch when it comes to reducing muscle soreness and improving performance after exercise.

In fact, there’s more research suggesting active recovery doesn’t have an effect than research showing it does have an effect.

While there could be several reasons for this, two stand out.

First, the way in which active recovery is applied in the research varies as lot. It’s likely there is a sweet spot in terms of how long active recovery should last to maximise its benefits (more on this later).

Second, it’s likely the benefits of active recovery are trivial to small. As such, they won’t always be considered “significant” in the scientific literature, despite offering potentially meaningful benefits at an individual level. In sport science, studies often have small sample sizes, which can make it hard to see small effects.

But there doesn’t seem to be any research suggesting active recovery is less effective than doing nothing, so at worst it certainly won’t cause any harm.

When is active recovery useful?

Active recovery appears useful if you need to perform multiple bouts of exercise within a short time frame. For example, if you were in a tournament and had 10–20 minutes between games, then a quick active recovery would be better than doing nothing.

Active recovery might also be a useful strategy if you have to perform exercise again within 24 hours after intense activity.

For example, if you are someone who plays sport and you need to play games on back-to-back days, doing some low-intensity active recovery after each game might help reduce soreness and improve performance on subsequent days.

Similarly, if you are training for an event like a marathon and you have a training session the day after a particularly long or intense run, then active recovery might get you better prepared for your next training session.

Conversely, if you have just completed a low-to-moderate intensity bout of exercise, it’s unlikely active recovery will offer the same benefits. And if you will get more than 24 hours of rest between exercise sessions, active recovery is unlikely to do much because this will probably be long enough for your body to recover naturally anyway.

Active recovery may be useful for people with back-to-back sporting commitments. Monkey Business Images/Shutterstock How to get the most out of active recovery

The good news is you don’t have to do a lot of active recovery to see a benefit.

A systematic review looking at the effectiveness of active recovery across 26 studies found 6–10 minutes of exercise was the sweet spot when it came to enhancing recovery.

Interestingly, the intensity of exercise didn’t seem to matter. If it was within this time frame, it had a positive effect.

So it makes sense to make your active recovery easy (because why would you make it hard if you don’t have to?) by keeping it in the light-to-moderate intensity range.

However, don’t expect active recovery to be a complete game changer. The research would suggest the benefits are likely to be small at best.

Hunter Bennett, Lecturer in Exercise Science, University of South Australia and Lewis Ingram, Lecturer in Physiotherapy, University of South Australia

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Don’t Forget…

Did you arrive here from our newsletter? Don’t forget to return to the email to continue learning!

Learn to Age Gracefully

Join the 98k+ American women taking control of their health & aging with our 100% free (and fun!) daily emails:

-

Nutrivore – by Dr. Sarah Ballantyne

10almonds is reader-supported. We may, at no cost to you, receive a portion of sales if you purchase a product through a link in this article.

The core idea of this book is that foods can be assigned a numerical value according to their total nutritional value, and that this number can be used to guide a person’s diet such that we will eat, in aggregate, a diet that is more nutritious. So far, so simple.

What Dr. Ballantyne also does, besides explaining and illustrating this system (there are chapters explaining the calculation system, and appendices with values), is also going over what to consider important and what we can let slide, and what things we might need more of to address a wide assortment of potential health concerns. And yes, this is definitely a “positive diet” approach, i.e. it focuses on what to add in, not what to cut out.

The premise of the “positive diet” approach is simple, by the way: if we get a full set of good nutrients, we will be satisfied and not crave unhealthy food.

She also offers a lot of helpful “rules of thumb”, and provides a variety of cheat-sheets and suchlike to make things as easy as possible.

There’s also a recipes section! Though, it’s not huge and it’s probably not necessary, but it’s just one more “she’s thinking of everything” element.

Bottom line: if you’d like a single-volume “Bible of” nutrition-made-easy, this is a very usable tome.

Click here to check out Nutrivore, and start filling up your diet!

Don’t Forget…

Did you arrive here from our newsletter? Don’t forget to return to the email to continue learning!

Learn to Age Gracefully

Join the 98k+ American women taking control of their health & aging with our 100% free (and fun!) daily emails:

-

Gluten: What’s The Truth?

10almonds is reader-supported. We may, at no cost to you, receive a portion of sales if you purchase a product through a link in this article.

Gluten: What’s The Truth?

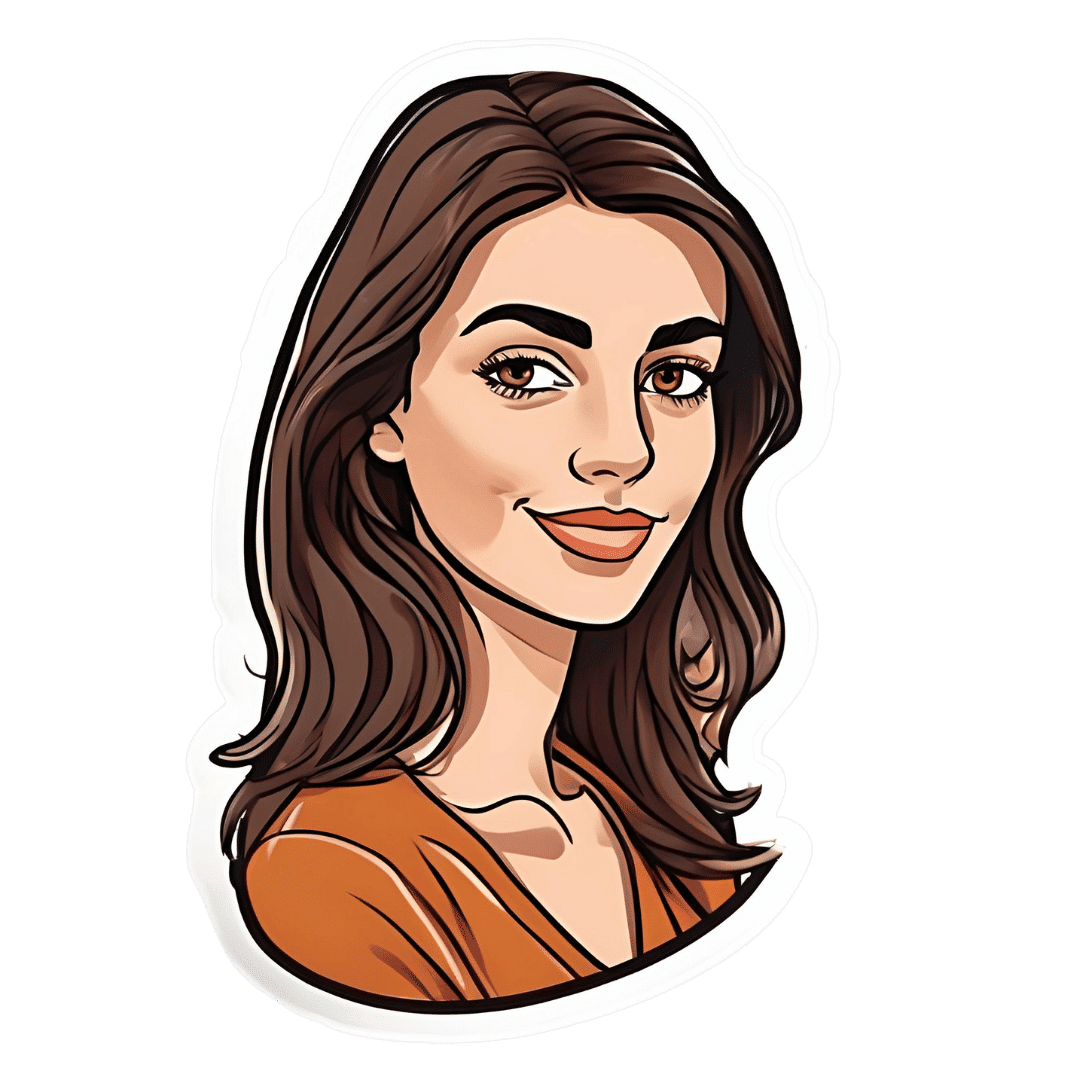

We asked you for your health-related view of gluten, and got the above spread of results. To put it simply:

Around 60% of voters voted for “Gluten is bad if you have an allergy/sensitivity; otherwise fine”

The rest of the votes were split fairly evenly between the other three options:

- Gluten is bad for everyone and we should avoid it

- Gluten is bad if (and only if) you have Celiac disease

- Gluten is fine for all, and going gluten-free is a modern fad

First, let’s define some terms so that we’re all on the same page:

What is gluten?

Gluten is a category of protein found in wheat, barley, rye, and triticale. As such, it’s not one single compound, but a little umbrella of similar compounds. However, for the sake of not making this article many times longer, we’re going to refer to “gluten” without further specification.

What is Celiac disease?

Celiac disease is an autoimmune disease. Like many autoimmune diseases, we don’t know for sure how/why it occurs, but a combination of genetic and environmental factors have been strongly implicated, with the latter putatively including overexposure to gluten.

It affects about 1% of the world’s population, and people with Celiac disease will tend to respond adversely to gluten, notably by inflammation of the small intestine and destruction of enterocytes (the cells that line the wall of the small intestine). This in turn causes all sorts of other problems, beyond the scope of today’s main feature, but suffice it to say, it’s not pleasant.

What is an allergy/intolerance/sensitivity?

This may seem basic, but a lot of people conflate allergy/intolerance/sensitivity, so:

- An allergy is when the body mistakes a harmless substance for something harmful, and responds inappropriately. This can be mild (e.g. allergic rhinitis, hayfever) or severe (e.g. peanut allergy), and as such, responses can vary from “sniffly nose” to “anaphylactic shock and death”.

- In the case of a wheat allergy (for example), this is usually somewhere between the two, and can for example cause breathing problems after ingesting wheat or inhaling wheat flour.

- An intolerance is when the body fails to correctly process something it should be able to process, and just ejects it half-processed instead.

- A common and easily demonstrable example is lactose intolerance. There isn’t a well-defined analog for gluten, but gluten intolerance is nonetheless a well-reported thing.

- A sensitivity is when none of the above apply, but the body nevertheless experiences unpleasant symptoms after exposure to a substance that should normally be safe.

- In the case of gluten, this is referred to as non-Celiac gluten sensitivity

A word on scientific objectivity: at 10almonds we try to report science as objectively as possible. Sometimes people have strong feelings on a topic, especially if it is polarizing.

Sometimes people with a certain condition feel constantly disbelieved and mocked; sometimes people without a certain condition think others are imagining problems for themselves where there are none.

We can’t diagnose anyone or validate either side of that, but what we can do is report the facts as objectively as science can lay them out.

Gluten is fine for all, and going gluten-free is a modern fad: True or False?

Definitely False, Celiac disease is a real autoimmune disease that cannot be faked, and allergies are also a real thing that people can have, and again can be validated in studies. Even intolerances have scientifically measurable symptoms and can be tested against nocebo.

See for example:

- Epidemiology and clinical presentations of Celiac disease

- Severe forms of food allergy that can precipitate allergic emergencies

- Properties of gluten intolerance: gluten structure, evolution, and pathogenicity

However! It may not be a modern fad, so much as a modern genuine increase in incidence.

Widespread varieties of wheat today contain a lot more gluten than wheat of ages past, and many other molecular changes mean there are other compounds in modern grains that never even existed before.

However, the health-related impact of these (novel proteins and carbohydrates) is currently still speculative, and we are not in the business of speculating, so we’ll leave that as a “this hasn’t been studied enough to comment yet but we recognize it could potentially be a thing” factor.

Gluten is bad if (and only if) you have Celiac disease: True or False?

Definitely False; allergies for example are well-evidenced as real; same facts as we discussed/linked just above.

Gluten is bad for everyone and we should avoid it: True or False?

False, tentatively and contingently.

First, as established, there are people with clinically-evidenced Celiac disease, wheat allergy, or similar. Obviously, they should avoid triggering those diseases.

What about the rest of us, and what about those who have non-Celiac gluten sensitivity?

Clinical testing has found that of those reporting non-Celiac gluten sensitivity, nocebo-controlled studies validate that diagnosis in only a minority of cases.

In the following study, for example, only 16% of those reporting symptoms showed them in the trials, and 40% of those also showed a nocebo response (i.e., like placebo, but a bad rather than good effect):

This one, on the other hand, found that positive validations of diagnoses were found to be between 7% and 77%, depending on the trial, with an average of 30%:

Re-challenge Studies in Non-celiac Gluten Sensitivity: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis

In other words: non-Celiac gluten sensitivity is a thing, and/but may be over-reported, and/but may be in some part exacerbated by psychosomatic effect.

Note: psychosomatic effect does not mean “imagining it” or “all in your head”. Indeed, the “soma” part of the word “psychosomatic” has to do with its measurable effect on the rest of the body.

For example, while pain can’t be easily objectively measured, other things, like inflammation, definitely can.

As for everyone else? If you’re enjoying your wheat (or similar) products, it’s well-established that they should be wholegrain for the best health impact (fiber, a positive for your health, rather than white flour’s super-fast metabolites padding the liver and causing metabolic problems).

Wheat itself may have other problems, for example FODMAPs, amylase trypsin inhibitors, and wheat germ agglutinins, but that’s “a wheat thing” rather than “a gluten thing”.

That’s beyond the scope of today’s main feature, but you might want to check out today’s featured book!

For a final scientific opinion on this last one, though, here’s what a respected academic journal of gastroenterology has to say:

From coeliac disease to noncoeliac gluten sensitivity; should everyone be gluten-free?

Don’t Forget…

Did you arrive here from our newsletter? Don’t forget to return to the email to continue learning!

Learn to Age Gracefully

Join the 98k+ American women taking control of their health & aging with our 100% free (and fun!) daily emails: