Why You Can’t Just “Get Over” Trauma

10almonds is reader-supported. We may, at no cost to you, receive a portion of sales if you purchase a product through a link in this article.

Time does not, in fact, heal all wounds. Sometimes they even compound themselves over time. Dr. Tracey Marks explains the damage that trauma does—the physiological presentation of “the axe forgets but the tree remembers”—and how to heal from that actual damage.

The science of healing

Trauma affects the mind and body (largely because the brain is, of course, both—and affects pretty much everything else), which can ripple out into all areas of life.

On the physical level, brain areas affected by trauma include:

- Amygdalae: becomes hyperactive, keeping a person in a heightened state of vigilance.

- Hippocampi: can shrink, causing fragmented or missing memories.

- Prefrontal cortex: reduces in activity, impairing decision-making and emotional regulation.

Trauma also activates the body’s fight or flight response, releasing stress hormones like cortisol and adrenaline. These are great things to have a pinch, but having them elevated all the time is equivalent to only ever driving your car at top speed—the only question becomes whether you’ll crash and burn before you break down.

However, there is hope! Neuroplasticity (the brain’s ability to rewire itself) can make trauma recovery possible through various interventions.

Evidence-based therapies for trauma include:

- Eye Movement Desensitization and Reprocessing (EMDR): this can help reprocess traumatic memories and reduce emotional intensity.

- Trauma-focused Cognitive Behavioral Therapy (CBT): this can help change unhelpful thought patterns and includes exposure therapy.

- Somatic therapies: these focus on the body and nervous system to release stored tension.

In this latter category, embodiment is key to trauma recovery—this may sound “wishy-washy”, but the evidence shows that reconnecting with the body does help manage emotional stress responses. Mind-body practices like mindfulness, yoga, and breathwork help cultivate embodiment and reduce trauma-related stress.

In short: you can’t just “get over” it, but with the right support and interventions, it’s possible to rewire the brain and body toward resilience and healing.

For more on all of this from Dr. Marks, enjoy:

Click Here If The Embedded Video Doesn’t Load Automatically!

Want to learn more?

You might also like to read:

- PTSD, But, Well…. Complex.

- Undoing The Damage Of Life’s Hard Knocks

- A Surprisingly Powerful Tool: Eye Movement Desensitization & Reprocessing

Take care!

Don’t Forget…

Did you arrive here from our newsletter? Don’t forget to return to the email to continue learning!

Recommended

Learn to Age Gracefully

Join the 98k+ American women taking control of their health & aging with our 100% free (and fun!) daily emails:

-

A short history of sunscreen, from basting like a chook to preventing skin cancer

10almonds is reader-supported. We may, at no cost to you, receive a portion of sales if you purchase a product through a link in this article.

Australians have used commercial creams, lotions or gels to manage our skin’s sun exposure for nearly a century.

But why we do it, the preparations themselves, and whether they work, has changed over time.

In this short history of sunscreen in Australia, we look at how we’ve slathered, slopped and spritzed our skin for sometimes surprising reasons.

At first, suncreams helped you ‘tan with ease’

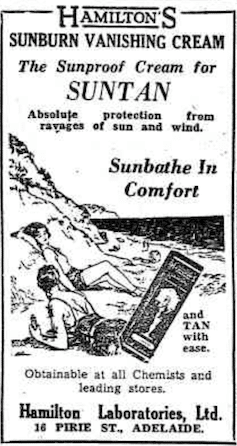

This early sunscreen claimed you could ‘tan with ease’.

Trove/NLASunscreens have been available in Australia since the 30s. Chemist Milton Blake made one of the first.

He used a kerosene heater to cook batches of “sunburn vanishing cream”, scented with French perfume.

His backyard business became H.A. Milton (Hamilton) Laboratories, which still makes sunscreens today.

Hamilton’s first cream claimed you could “

Sunbathe in Comfort and TAN with ease”. According to modern standards, it would have had an SPF (or sun protection factor) of 2.The mirage of ‘safe tanning’

A tan was considered a “modern complexion” and for most of the 20th century, you might put something on your skin to help gain one. That’s when “safe tanning” (without burning) was thought possible.

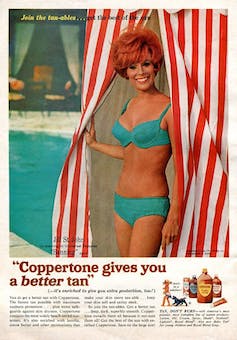

This 1967 Coppertone advertisement urged you to ‘tan, not burn’.

SenseiAlan/Flickr, CC BY-SASunburn was known to be caused by the UVB component of ultraviolet (UV) light. UVA, however, was thought not to be involved in burning; it was just thought to darken the skin pigment melanin. So, medical authorities advised that by using a sunscreen that filtered out UVB, you could “safely tan” without burning.

But that was wrong.

From the 70s, medical research suggested UVA penetrated damagingly deep into the skin, causing ageing effects such as sunspots and wrinkles. And both UVA and UVB could cause skin cancer.

Sunscreens from the 80s sought to be “broad spectrum” – they filtered both UVB and UVA.

Researchers consequently recommended sunscreens for all skin tones, including for preventing sun damage in people with dark skin.

Delaying burning … or encouraging it?

Up to the 80s, sun preparations ranged from something that claimed to delay burning, to preparations that actively encouraged it to get that desirable tan – think, baby oil or coconut oil. Sun-worshippers even raided the kitchen cabinet, slicking olive oil on their skin.

One manufacturer’s “sun lotion” might effectively filter UVB; another’s merely basted you like a roast chicken.

Since labelling laws before the 80s didn’t require manufacturers to list the ingredients, it was often hard for consumers to tell which was which.

At last, SPF arrives to guide consumers

In the 70s, two Queensland researchers, Gordon Groves and Don Robertson, developed tests for sunscreens – sometimes experimenting on students or colleagues. They printed their ranking in the newspaper, which the public could use to choose a product.

An Australian sunscreen manufacturer then asked the federal health department to regulate the industry. The company wanted standard definitions to market their products, backed up by consistent lab testing methods.

In 1986, after years of consultation with manufacturers, researchers and consumers, Australian Standard AS2604 gave a specified a testing method, based on the Queensland researchers’ work. We also had a way of expressing how well sunscreens worked – the sun protection factor or SPF.

This is the ratio of how long it takes a fair-skinned person to burn using the product compared with how long it takes to burn without it. So a cream that protects the skin sufficiently so it takes 40 minutes to burn instead of 20 minutes has an SPF of 2.

Manufacturers liked SPF because businesses that invested in clever chemistry could distinguish themselves in marketing. Consumers liked SPF because it was easy to understand – the higher the number, the better the protection.

Australians, encouraged from 1981 by the Slip! Slop! Slap! nationwide skin cancer campaign, could now “slop” on a sunscreen knowing the degree of protection it offered.

How about skin cancer?

It wasn’t until 1999 that research proved that using sunscreen prevents skin cancer. Again, we have Queensland to thank, specifically the residents of Nambour. They took part in a trial for nearly five years, carried out by a research team led by Adele Green of the Queensland Institute of Medical Research. Using sunscreen daily over that time reduced rates of squamous cell carcinoma (a common form of skin cancer) by about 60%.

Follow-up studies in 2011 and 2013 showed regular sunscreen use almost halved the rate of melanoma and slowed skin ageing. But there was no impact on rates of basal cell carcinoma, another common skin cancer.

By then, researchers had shown sunscreen stopped sunburn, and stopping sunburn would prevent at least some types of skin cancer.

What’s in sunscreen today?

An effective sunscreen uses one or more active ingredients in a cream, lotion or gel. The active ingredient either works:

-

“chemically” by absorbing UV and converting it to heat. Examples include PABA (para-aminobenzoic acid) and benzyl salicylate, or

-

“physically” by blocking the UV, such as zinc oxide or titanium dioxide.

Physical blockers at first had limited cosmetic appeal because they were opaque pastes. (Think cricketers with zinc smeared on their noses.)

With microfine particle technology from the 90s, sunscreen manufacturers could then use a combination of chemical absorbers and physical blockers to achieve high degrees of sun protection in a cosmetically acceptable formulation.

Where now?

Australians have embraced sunscreen, but they still don’t apply enough or reapply often enough.

Although some people are concerned sunscreen will block the skin’s ability to make vitamin D this is unlikely. That’s because even SPF50 sunscreen doesn’t filter out all UVB.

There’s also concern about the active ingredients in sunscreen getting into the environment and whether their absorption by our bodies is a problem.

Sunscreens have evolved from something that at best offered mild protection to effective, easy-to-use products that stave off the harmful effects of UV. They’ve evolved from something only people with fair skin used to a product for anyone.

Remember, slopping on sunscreen is just one part of sun protection. Don’t forget to also slip (protective clothing), slap (hat), seek (shade) and slide (sunglasses).

Laura Dawes, Research Fellow in Medico-Legal History, Australian National University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Share This Post

-

-

Acid Reflux Diet Cookbook – by Dr. Harmony Reynolds

10almonds is reader-supported. We may, at no cost to you, receive a portion of sales if you purchase a product through a link in this article.

Notwithstanding the title, this is far more than just a recipe book. Of course, it is common for health-focused recipe books to begin with a preamble about the science that’s going to be applied, but in this case, the science makes up a larger portion of the book than usual, along with practical tips about how to best implement certain things, at home and when out and about.

Dr. Reynolds also gives a lot of information about such things as medications that could be having an effect one way or the other, and even other lifestyle factors such as exercise and so forth, and yes, even stress management. Because for many people, what starts as acid reflux can soon become ulcers, and that’s not good.

The recipes themselves are diverse and fairly simple; they’re written solely with acid reflux in mind and not other health considerations, but they are mostly heathy in the generalized sense too.

The style is straight to the point with zero padding sensationalism, or chit-chat. It can make for a slightly dry read, but let’s face it, nobody is buying this book for its entertainment value.

Bottom line: if you have been troubled by acid reflux, this book will help you to eat your way safely out of it.

Click here to check out the Acid Reflux Diet Cookbook, and enjoy!

Share This Post

-

Honeydew vs Cantaloupe – Which is Healthier?

10almonds is reader-supported. We may, at no cost to you, receive a portion of sales if you purchase a product through a link in this article.

Our Verdict

When comparing honeydew to cantaloupe, we picked the cantaloupe.

Why?

In terms of macros, there’s not a lot between them—they’re both mostly water. Nominally, honeydew has more carbs while cantaloupe has more fiber and protein, but the differences are very small. So, a very slight win for cantaloupe.

Looking at vitamins: honeydew has slightly more of vitamins B5 and B6 (so, the vitamins that are in pretty much everything), while cantaloupe has a more of vitamins A, B1, B2, B3, C, and E (especially notably 67x more vitamin A, whence its color). A more convincing win for cantaloupe.

The minerals category is even more polarized: honeydew has more selenium (and for what it’s worth, more sodium too, though that’s not usually a plus for most of us in the industrialized world), while cantaloupe has more calcium, copper, iron, magnesium, manganese, phosphorus, potassium, and zinc. An overwhelming win for cantaloupe.

No surprises: adding up the slight win for cantaloupe, the convincing win for cantaloupe, and the overwhelming win for cantaloupe, makes cantaloupe the overall best pick here.

Enjoy!

Want to learn more?

You might like to read:

From Apples to Bees, and High-Fructose Cs: Which Sugars Are Healthier, And Which Are Just The Same?

Take care!

Share This Post

Related Posts

-

The Food For Life Cookbook – by Dr. Tim Spector

10almonds is reader-supported. We may, at no cost to you, receive a portion of sales if you purchase a product through a link in this article.

We’ve previously reviewed Dr. Spector’s “Food For Life”, and while that was more of an “explanatory science” book, this one takes that science (reiterating it more briefly this time, by way of introduction) and makes a cookbook of it.

The nutritional emphasis in these recipes is on two things: maximizing fiber, and maximizing plant diversity. The recipes are not all vegan or even vegetarian, but they are plant-centric, and if the reader is vegetarian/vegan, then substitutions are easy to make.

The recipes themselves are simple without being boring, and are easy to follow, with full-page photos to accompany them. The science parts are very clear, accessible, and pop-science in style.

Bottom line: if you’d like to incorporate more fiber and more plants into your diet without it being a burden, this book is great for that.

Click here to check out the Food For Life Cookbook, and get cooking for life!

Don’t Forget…

Did you arrive here from our newsletter? Don’t forget to return to the email to continue learning!

Learn to Age Gracefully

Join the 98k+ American women taking control of their health & aging with our 100% free (and fun!) daily emails:

-

Ruminating vs Processing

10almonds is reader-supported. We may, at no cost to you, receive a portion of sales if you purchase a product through a link in this article.

When it comes to traumatic experiences, there are two common pieces of advice for being able to move forwards functionally:

- Process whatever thoughts and feelings you need to process

- Do not ruminate

The latter can seem, at first glance, a lot like the former. So, how to tell them apart, and how to do one without the other?

Getting tense

One major difference between the two is the tense in which our mental activity takes place:

- processing starts with the traumatic event (or perhaps even the events leading up to the traumatic event), analyses what happened and if possible why, and then asks the question “ok, what now?” and begins work on laying out a path for the future.

- rumination starts with the traumatic event (or perhaps even the events leading up to the traumatic event), analyses what happened and if why, oh why oh why, “I was such an idiot, if only I had…” and gets trapped in a fairly tight (and destructive*) cycle of blame and shame/anger, never straying far from the events in question.

*this may be directly self-destructive, but it can also sometimes be only indirectly self-destructive, for example if the blame and anger is consciously placed with someone else.

This idea fits in, by the way, with Dr. Elisabeth Kübler-Ross’s “five stages of grief” model; rumination here represents the stages “bargaining”, “despair”, and “anger”, while emotional processing here represents the stage “acceptance”. Thus, it may be that rumination does have a place in the overall process—just don’t get stuck there!

For more on healthily processing grief specifically:

What Grief Does To The Body (And How To Manage It)

Grief, by the way, can be about more than the loss of a loved one; a very similar process can play out with many other kinds of unwanted life changes too.

What are the results?

Another way to tell them apart is to look at the results of each. If you come out of a long rumination session feeling worse than when you started, it’s highly unlikely that you just stopped too soon and were on the verge of some great breakthrough. It’s possible! But not likely.

- Processing may be uncomfortable at first, and if it’s something you’ve ignored for a long time, that could be very uncomfortable at first, but there should quite soon be some “light at the end of the tunnel”. Perhaps not even because a solution seems near, but because your mind and body recognize “aha, we are doing something about it now, and thus may find a better way forward”.

- Rumination tends to intensify and prolong uncomfortable emotions, increases stress and anxiety, and likely disrupts sleep. At best, it may serve as a tipping point to seek therapy or even just recognize “I should figure out a way to deal with this, because this isn’t doing me any good”. At worst, it may serve as a tipping point to depression, and/or substance abuse, and/or suicidality.

See also: How To Stay Alive (When You Really Don’t Want To) ← which also has a link back to our article on managing depression, by the way!

Did you choose it, really?

A third way to tell them apart is the level of conscious decision that went into doing it.

- Processing is almost always something that one decides “ok, let’s figure this out”, and sits down to figure it out.

- Rumination tends to be about as voluntary as social media doomscrolling. Technically we may have decided to begin it (we also might not have made any conscious decision, and just acted on impulse), but let’s face it, our hands weren’t at the wheel for long, at all.

A good way to make sure that it is a conscious process, is to schedule time for it in advance, and then do it only during that time. If thoughts about it come up at other times, tell yourself “no, leave that for later”, and then deal with it when (and only when) the planned timeslot arrives.

It’s up to you and your schedule what time you pick, but if you’re unsure, consider an hour in the early evening. That means that the business of the day is behind you, but it’s also not right before bed, so you should have some decompression time as a buffer. So for example, perhaps after dinner you might set a timer* for an hour, and sit down to journal, brainstorm, or just plain think, about the matter that needs processing.

*electronic timers can be quite jarring, and may distract you while waiting for the beeps. So, consider investing in a relaxing sand timer like this one instead.

Is there any way to make rumination less bad?

As we mentioned up top, there’s a case to be made for “rumination is an early part of the process that gets us where we need to go, and may not be skippable, or may not be advisable to skip”.

So, if you are going to ruminate, then firstly, we recommend again bordering it timewise (with a timer as above) and having a plan to pull yourself out when you’re done rather than getting stuck there (such as: The Off-Button For Your Brain: How To Stop Negative Thought Spirals).

And secondly, you might want to consider the following technique, which allows one to let one’s brain know that the thing we’re thinking about / imagining is now to be filed away safely; not lost or erased, but sent to the same place that nightmares go after we wake up:

A Surprisingly Powerful Tool: Eye Movement Desensitization & Reprocessing (EMDR)

What if I actually do want to forget?

That’s not usually recommendable; consider talking it through with a therapist first. However, for your interest, there is a way:

The Dark Side Of Memory (And How To Forget)

Take care!

Don’t Forget…

Did you arrive here from our newsletter? Don’t forget to return to the email to continue learning!

Learn to Age Gracefully

Join the 98k+ American women taking control of their health & aging with our 100% free (and fun!) daily emails:

-

Shrimp vs Caviar – Which is Healthier?

10almonds is reader-supported. We may, at no cost to you, receive a portion of sales if you purchase a product through a link in this article.

Our Verdict

When comparing shrimp to caviar, we picked the caviar.

Why?

Both of these seafoods share a common history (also shared with lobster, by the way) of “nutrient-dense peasant-food that got gentrified and now it’s more expensive despite being easier to source”. But, cost and social quirks aside, what are their strengths and weaknesses?

In terms of macros, both are high in protein, but caviar is much higher in fat. You may be wondering: are the fats healthy? And the answer is that it’s a fairly even mix between monounsaturated (healthy), polyunsaturated (healthy), and saturated (unhealthy). The fact that caviar is generally enjoyed in very small portions is its saving grace here, but quantity for quantity, shrimp is the natural winner on macros.

…unless we take into account the omega-3 and omega-6 balance, in which case, it’s worthy of note that caviar has more omega-3 (which most people could do with consuming more of) while shrimp has more omega-6 (which most people could do with consuming less of).

When it comes to vitamins, caviar has more of vitamins A, B1, B2, B5, B6, B9, B12, D, K, and choline; nor are the margins small in most cases, being multiples (or sometimes, tens of multiples) higher. Shrimp, meanwhile, boasts only more vitamin B3.

In the category of minerals, caviar leads with more calcium, iron, magnesium, manganese, phosphorus, potassium, and selenium, while shrimp has more copper and zinc.

All in all, while shrimp has its benefits for being lower in fat (and thus also, for those whom that may interest, lower in calories), caviar wins the day by virtue of its overwhelming nutritional density.

Want to learn more?

You might like to read:

What Omega-3 Fatty Acids Really Do For Us

Take care!

Don’t Forget…

Did you arrive here from our newsletter? Don’t forget to return to the email to continue learning!

Learn to Age Gracefully

Join the 98k+ American women taking control of their health & aging with our 100% free (and fun!) daily emails: