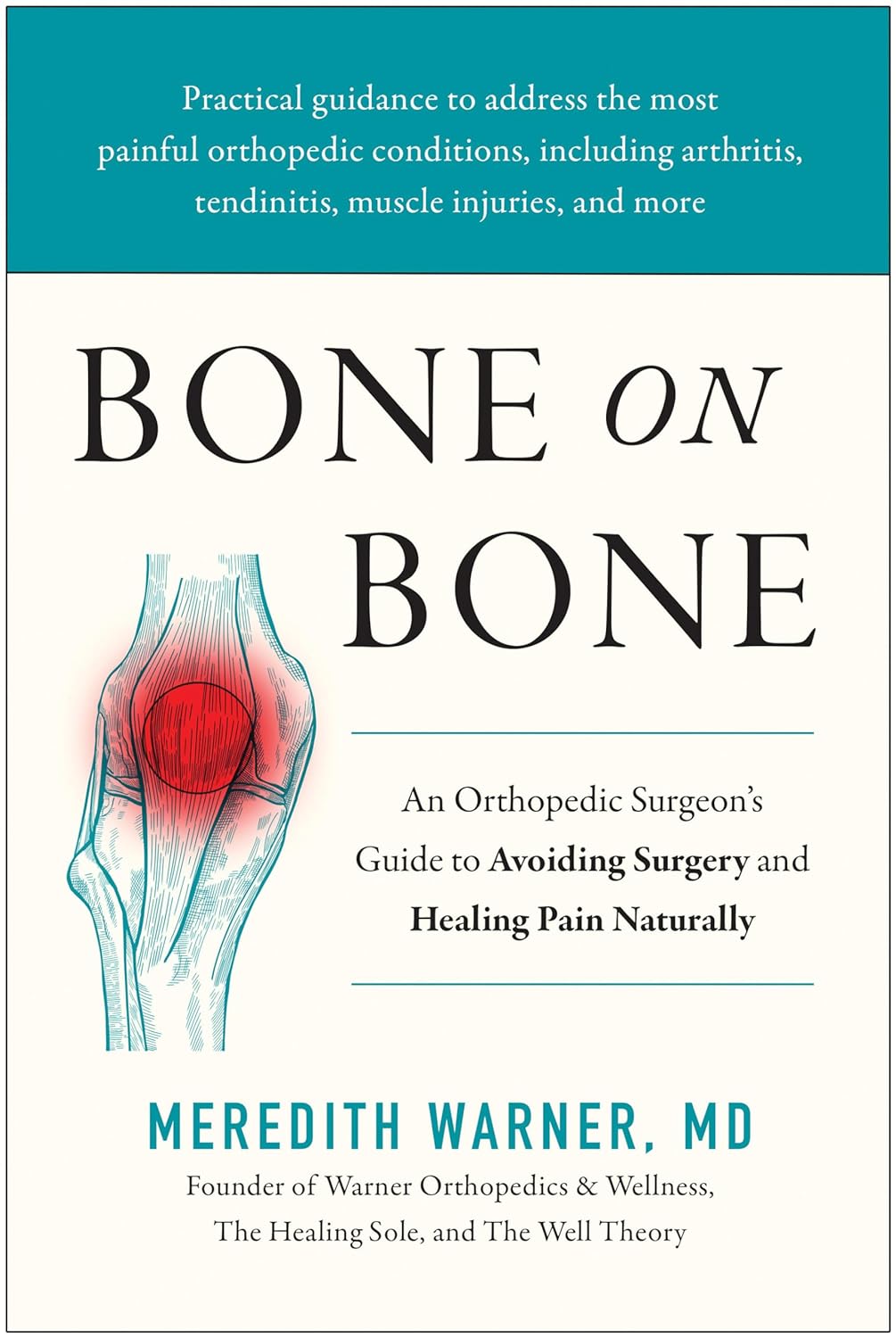

Bone on Bone – by Dr. Meredith Warner

10almonds is reader-supported. We may, at no cost to you, receive a portion of sales if you purchase a product through a link in this article.

What this is not: a book about one specific condition, injury, or surgery.

What this is: a guide to dealing with the common factors of many musculoskeletal conditions, inflammatory diseases, and their consequences.

Dr. Warner takes the opportunity to address the whole patient—presumably: the reader, though it could equally be a reader’s loved one, or even a reader’s patient, insofar as this book will probably be read by doctors also.

She takes an “inside-out and outside-in” approach; that is to say, addressing the problem from as many vectors as reasonably possible—including supplements, diet, dietary habits (things like intermittent fasting etc), exercise, and even sleep. And yes, she knows how difficult those latter items can be, and addresses them not merely with a “but it’s important” but also with practical advice.

As an orthopedic surgeon, she’s not a fan of surgery, and counsels the reader to avoid that if reasonably possible. She also talks about how many people in the US are encouraged to have MRI scans for financial reasons (as in, they can be profitable for the doctor/institution), and then any abnormality is used as justification for surgery, to backwards-justify the use of the MRI, even if the abnormality is not actually the cause of the pain.

Noteworthily, humans in general are a typically a pile of abnormalities in a trenchcoat. Our propensity to mutation has made us one of the most adaptable species on the planet, yet many would have us pretend that the insides of people look like they do in textbooks, or else are wrong. The reality is not so, and Dr. Warner rightly shows this for what it is.

Bottom line: if you or a loved one are suffering from, or at risk of, musculoskeletal and/or inflammatory conditions, this is a top-tier book for having a much easier time of it.

Don’t Forget…

Did you arrive here from our newsletter? Don’t forget to return to the email to continue learning!

Recommended

Learn to Age Gracefully

Join the 98k+ American women taking control of their health & aging with our 100% free (and fun!) daily emails:

-

If I’m diagnosed with one cancer, am I likely to get another?

10almonds is reader-supported. We may, at no cost to you, receive a portion of sales if you purchase a product through a link in this article.

Receiving a cancer diagnosis is life-changing and can cause a range of concerns about ongoing health.

Fear of cancer returning is one of the top health concerns. And managing this fear is an important part of cancer treatment.

But how likely is it to get cancer for a second time?

Why can cancer return?

While initial cancer treatment may seem successful, sometimes a few cancer cells remain dormant. Over time, these cancer cells can grow again and may start to cause symptoms.

This is known as cancer recurrence: when a cancer returns after a period of remission. This period could be days, months or even years. The new cancer is the same type as the original cancer, but can sometimes grow in a new location through a process called metastasis.

Actor Hugh Jackman has gone public about his multiple diagnoses of basal cell carcinoma (a type of skin cancer) over the past decade.

The exact reason why cancer returns differs depending on the cancer type and the treatment received. Research is ongoing to identify genes associated with cancers returning. This may eventually allow doctors to tailor treatments for high-risk people.

What are the chances of cancer returning?

The risk of cancer returning differs between cancers, and between sub-types of the same cancer.

New screening and treatment options have seen reductions in recurrence rates for many types of cancer. For example, between 2004 and 2019, the risk of colon cancer recurring dropped by 31-68%. It is important to remember that only someone’s treatment team can assess an individual’s personal risk of cancer returning.

For most types of cancer, the highest risk of cancer returning is within the first three years after entering remission. This is because any leftover cancer cells not killed by treatment are likely to start growing again sooner rather than later. Three years after entering remission, recurrence rates for most cancers decrease, meaning that every day that passes lowers the risk of the cancer returning.

Every day that passes also increases the numbers of new discoveries, and cancer drugs being developed.

What about second, unrelated cancers?

Earlier this year, we learned Sarah Ferguson, Duchess of York, had been diagnosed with malignant melanoma (a type of skin cancer) shortly after being treated for breast cancer.

Although details have not been confirmed, this is likely a new cancer that isn’t a recurrence or metastasis of the first one.

Australian research from Queensland and Tasmania shows adults who have had cancer have around a 6-36% higher risk of developing a second primary cancer compared to the risk of cancer in the general population.

Who’s at risk of another, unrelated cancer?

With improvements in cancer diagnosis and treatment, people diagnosed with cancer are living longer than ever. This means they need to consider their long-term health, including their risk of developing another unrelated cancer.

Reasons for such cancers include different types of cancers sharing the same kind of lifestyle, environmental and genetic risk factors.

The increased risk is also likely partly due to the effects that some cancer treatments and imaging procedures have on the body. However, this increased risk is relatively small when compared with the (sometimes lifesaving) benefits of these treatment and procedures.

While a 6-36% greater chance of getting a second, unrelated cancer may seem large, only around 10-12% of participants developed a second cancer in the Australian studies we mentioned. Both had a median follow-up time of around five years.

Similarly, in a large US study only about one in 12 adult cancer patients developed a second type of cancer in the follow-up period (an average of seven years).

The kind of first cancer you had also affects your risk of a second, unrelated cancer, as well as the type of second cancer you are at risk of. For example, in the two Australian studies we mentioned, the risk of a second cancer was greater for people with an initial diagnosis of head and neck cancer, or a haematological (blood) cancer.

People diagnosed with cancer as a child, adolescent or young adult also have a greater risk of a second, unrelated cancer.

What can I do to lower my risk?

Regular follow-up examinations can give peace of mind, and ensure any subsequent cancer is caught early, when there’s the best chance of successful treatment.

Maintenance therapy may be used to reduce the risk of some types of cancer returning. However, despite ongoing research, there are no specific treatments against cancer recurrence or developing a second, unrelated cancer.

But there are things you can do to help lower your general risk of cancer – not smoking, being physically active, eating well, maintaining a healthy body weight, limiting alcohol intake and being sun safe. These all reduce the chance of cancer returning and getting a second cancer.

Sarah Diepstraten, Senior Research Officer, Blood Cells and Blood Cancer Division, Walter and Eliza Hall Institute and Terry Boyle, Senior Lecturer in Cancer Epidemiology, University of South Australia

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Share This Post

-

Falling: Is It Due To Age Or Health Issues?

10almonds is reader-supported. We may, at no cost to you, receive a portion of sales if you purchase a product through a link in this article.

It’s Q&A Day at 10almonds!

Have a question or a request? We love to hear from you!

In cases where we’ve already covered something, we might link to what we wrote before, but will always be happy to revisit any of our topics again in the future too—there’s always more to say!

As ever: if the question/request can be answered briefly, we’ll do it here in our Q&A Thursday edition. If not, we’ll make a main feature of it shortly afterwards!

So, no question/request too big or small 😎

❝What are the signs that a senior is falling due to health issues rather than just aging?❞

Superficial answer: having an ear infection can result in a loss of balance, and is not particularly tied to age as a risk factor

More useful answer: first, let’s consider these two true statements:

- The risks of falling (both the probability and the severity of consequences) increase with age

- Health issues (in general) tend to increase with age

With this in mind, it’s difficult to disconnect the two, as neither exist in a vacuum, and each is strongly associated with the other.

So the question is easier to answer by first flipping it, to ask:

❝What are the health issues that typically increase with age, that increase the chances of falling?❞

A non-exhaustive list includes:

- Loss of strength due to sarcopenia (reduced muscle mass)

- Loss of mobility due to increased stiffness (many causes, most of which worsen with age)

- Loss of risk-awareness due to diminished senses (for example, not seeing an obstacle until too late)

- Loss of risk-awareness due to reduced mental focus (cognitive decline producing absent-mindedness)

Note that in the last example there, and to a lesser extent the third one, reminds us that falls also often do not happen in a vacuum. There is (despite how it may sometimes feel!) no actual change in our physical relationship with gravity as we get older; most falls are about falling over things, even if it’s just one’s own feet:

The 4 Bad Habits That Cause The Most Falls While Walking

Disclaimer: sometimes a person may just fall down for no external reason. An example of why this may happen is if a person’s joint (for example an ankle or a knee) has a particular weakness that means it’ll occasionally just buckle and collapse under one’s own weight. This doesn’t even have to be a lot of weight! The weakness could be due to an old injury, or Ehlers-Danlos Syndrome (with its characteristic joint hypermobility symptoms), or something else entirely.

Now, notice how:

- all of these things can happen at any age

- all of these things are more likely to happen the older we get

- none of these things have to happen at any age

That last one’s important to remember! Aging is often viewed as an implacable Behemoth, but the truth is that it is many-faceted and every single one of those facets can be countered, to a greater or lesser degree.

Think of a room full of 80-year-olds, and now imagine that…

- One has the hearing of a 20-year-old

- One has the eyesight of a 20-year-old

- One has the sharp quick mind of a 20-year-old

- One has the cardiovascular fitness of a 20-year-old

…etc. Now, none of those things in isolation is unthinkable, so remember, there is no magic law of the universe saying we can’t have each of them:

Age & Aging: What Can (And Can’t) We Do About It?

Which means: that goes for the things that increase the risk of falling, too. In other words, we can combat sarcopenia with protein and resistance training, maintain our mobility, look after our sensory organs as best we can, nourish our brain and keep it sharp, etc etc etc:

Train For The Event Of Your Life! (Mobility As A Long-Term “Athletic” Goal For Personal Safety)

Which doesn’t mean: that we will necessarily succeed in all areas. Your writer here, broadly in excellent health, and whose lower body is still a veritable powerhouse in athletic terms, has a right ankle and left knee that will sometimes just buckle (yay, the aforementioned hypermobility).

So, it becomes a priority to pre-empt the consequences of that, for example:

- being able to fall with minimal impact (this is a matter of knowing how, and can be learned from “soft” martial arts such as aikido), and

- ensuring the skeleton can take a knock if necessary (keeping a good balance of vitamins, minerals, protein, etc; keeping an eye on bone density).

See also:

Fall Special ← appropriate for the coming season, but it’s about avoiding falling, and reducing the damage of falling if one does fall, including some exercises to try at home.

Take care!

Share This Post

-

Biohack Your Brain – by Dr. Kristen Willeumier

10almonds is reader-supported. We may, at no cost to you, receive a portion of sales if you purchase a product through a link in this article.

The title of this book is a little misleading, as it’s not really about biohacking; it’s more like a care and maintenance manual for the brain.

This distinction is relevant, because to hack a thing is to use it in a way it’s not supposed to be used, and/or get it to do something it’s not supposed to do.

Intead, what neurobiologist Dr. Kristen Willeumier offers us is much more important: how to keep our brain in good condition.

She takes us through the various things that our brain needs, and what will happen if it doesn’t get them. Some are dietary, some are behavioral, some are even cognitive.

A strength of this book is not just explaining what things are good for the brain, but also: why. Understanding the “why” can be the motivational factor that makes a difference between us doing the thing or not!

For example, if we know that exercise is good for the brain, we think “sounds reasonable” and carry on with what we were doing. If, however, we also understand how increased bloodflow helps with the timely removal of beta-amyloids that are associated with Alzheimer’s, we’re more likely to make time for getting that movement going.

Bottom line: there are key things we can do to keep our brain healthy, and you probably wouldn’t want to miss any. This book is a great care manual for such!

Click here to check out Biohack Your Brain and keep your brain young and fit!

Share This Post

Related Posts

-

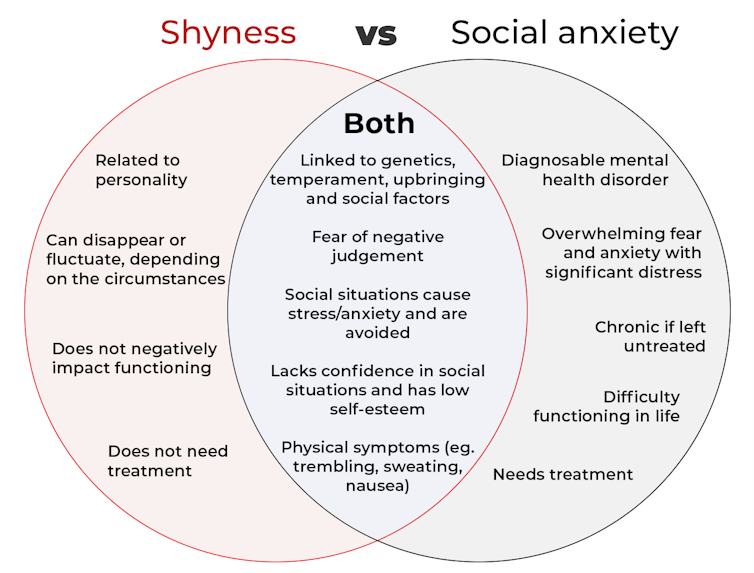

What’s the difference between shyness and social anxiety?

10almonds is reader-supported. We may, at no cost to you, receive a portion of sales if you purchase a product through a link in this article.

What’s the difference? is a new editorial product that explains the similarities and differences between commonly confused health and medical terms, and why they matter.

The terms “shyness” and “social anxiety” are often used interchangeably because they both involve feeling uncomfortable in social situations.

However, feeling shy, or having a shy personality, is not the same as experiencing social anxiety (short for “social anxiety disorder”).

Here are some of the similarities and differences, and what the distinction means.

pathdoc/Shutterstock How are they similar?

It can be normal to feel nervous or even stressed in new social situations or when interacting with new people. And everyone differs in how comfortable they feel when interacting with others.

For people who are shy or socially anxious, social situations can be very uncomfortable, stressful or even threatening. There can be a strong desire to avoid these situations.

People who are shy or socially anxious may respond with “flight” (by withdrawing from the situation or avoiding it entirely), “freeze” (by detaching themselves or feeling disconnected from their body), or “fawn” (by trying to appease or placate others).

A complex interaction of biological and environmental factors is also thought to influence the development of shyness and social anxiety.

For example, both shy children and adults with social anxiety have neural circuits that respond strongly to stressful social situations, such as being excluded or left out.

People who are shy or socially anxious commonly report physical symptoms of stress in certain situations, or even when anticipating them. These include sweating, blushing, trembling, an increased heart rate or hyperventilation.

How are they different?

Social anxiety is a diagnosable mental health condition and is an example of an anxiety disorder.

For people who struggle with social anxiety, social situations – including social interactions, being observed and performing in front of others – trigger intense fear or anxiety about being judged, criticised or rejected.

To be diagnosed with social anxiety disorder, social anxiety needs to be persistent (lasting more than six months) and have a significant negative impact on important areas of life such as work, school, relationships, and identity or sense of self.

Many adults with social anxiety report feeling shy, timid and lacking in confidence when they were a child. However, not all shy children go on to develop social anxiety. Also, feeling shy does not necessarily mean a person meets the criteria for social anxiety disorder.

People vary in how shy or outgoing they are, depending on where they are, who they are with and how comfortable they feel in the situation. This is particularly true for children, who sometimes appear reserved and shy with strangers and peers, and outgoing with known and trusted adults.

Individual differences in temperament, personality traits, early childhood experiences, family upbringing and environment, and parenting style, can also influence the extent to which people feel shy across social situations.

Not all shy children go on to develop social anxiety. 249 Anurak/Shutterstock However, people with social anxiety have overwhelming fears about embarrassing themselves or being negatively judged by others; they experience these fears consistently and across multiple social situations.

The intensity of this fear or anxiety often leads people to avoid situations. If avoiding a situation is not possible, they may engage in safety behaviours, such as looking at their phone, wearing sunglasses or rehearsing conversation topics.

The effect social anxiety can have on a person’s life can be far-reaching. It may include low self-esteem, breakdown of friendships or romantic relationships, difficulties pursuing and progressing in a career, and dropping out of study.

The impact this has on a person’s ability to lead a meaningful and fulfilling life, and the distress this causes, differentiates social anxiety from shyness.

Children can show similar signs or symptoms of social anxiety to adults. But they may also feel upset and teary, irritable, have temper tantrums, cling to their parents, or refuse to speak in certain situations.

If left untreated, social anxiety can set children and young people up for a future of missed opportunities, so early intervention is key. With professional and parental support, patience and guidance, children can be taught strategies to overcome social anxiety.

Why does the distinction matter?

Social anxiety disorder is a mental health condition that persists for people who do not receive adequate support or treatment.

Without treatment, it can lead to difficulties in education and at work, and in developing meaningful relationships.

Receiving a diagnosis of social anxiety disorder can be validating for some people as it recognises the level of distress and that its impact is more intense than shyness.

A diagnosis can also be an important first step in accessing appropriate, evidence-based treatment.

Different people have different support needs. However, clinical practice guidelines recommend cognitive-behavioural therapy (a kind of psychological therapy that teaches people practical coping skills). This is often used with exposure therapy (a kind of psychological therapy that helps people face their fears by breaking them down into a series of step-by-step activities). This combination is effective in-person, online and in brief treatments.

Treatment is available online as well as in-person. ImYanis/Shutterstock For more support or further reading

Online resources about social anxiety include:

- This Way Up’s online program for managing excessive shyness and fear of social situations

- Beyond Blue’s resources on social anxiety

- a guide to looking after yourself if you have social anxiety, from the Western Australian health department

- social anxiety online program for children and teens from the University of Queensland

- inroads, a self-guided online program for young adults who drink alcohol to manage their anxiety.

We thank the Black Dog Institute Lived Experience Advisory Network members for providing feedback and input for this article and our research.

Kayla Steele, Postdoctoral research fellow and clinical psychologist, UNSW Sydney and Jill Newby, Professor, NHMRC Emerging Leader & Clinical Psychologist, UNSW Sydney

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Don’t Forget…

Did you arrive here from our newsletter? Don’t forget to return to the email to continue learning!

Learn to Age Gracefully

Join the 98k+ American women taking control of their health & aging with our 100% free (and fun!) daily emails:

-

Terminal lucidity: why do loved ones with dementia sometimes ‘come back’ before death?

10almonds is reader-supported. We may, at no cost to you, receive a portion of sales if you purchase a product through a link in this article.

Dementia is often described as “the long goodbye”. Although the person is still alive, dementia slowly and irreversibly chips away at their memories and the qualities that make someone “them”.

Dementia eventually takes away the person’s ability to communicate, eat and drink on their own, understand where they are, and recognise family members.

Since as early as the 19th century, stories from loved ones, caregivers and health-care workers have described some people with dementia suddenly becoming lucid. They have described the person engaging in meaningful conversation, sharing memories that were assumed to have been lost, making jokes, and even requesting meals.

It is estimated 43% of people who experience this brief lucidity die within 24 hours, and 84% within a week.

Why does this happen?

Terminal lucidity or paradoxical lucidity?

In 2009, researchers Michael Nahm and Bruce Greyson coined the term “terminal lucidity”, since these lucid episodes often occurred shortly before death.

But not all lucid episodes indicate death is imminent. One study found many people with advanced dementia will show brief glimmers of their old selves more than six months before death.

Lucidity has also been reported in other conditions that affect the brain or thinking skills, such as meningitis, schizophrenia, and in people with brain tumours or who have sustained a brain injury.

Moments of lucidity that do not necessarily indicate death are sometimes called paradoxical lucidity. It is considered paradoxical as it defies the expected course of neurodegenerative diseases such as dementia.

But it’s important to note these episodes of lucidity are temporary and sadly do not represent a reversal of neurodegenerative disease.

Sadly, these episodes of lucidity are only temporary. Pexels/Kampus Production Why does terminal lucidity happen?

Scientists have struggled to explain why terminal lucidity happens. Some episodes of lucidity have been reported to occur in the presence of loved ones. Others have reported that music can sometimes improve lucidity. But many episodes of lucidity do not have a distinct trigger.

A research team from New York University speculated that changes in brain activity before death may cause terminal lucidity. But this doesn’t fully explain why people suddenly recover abilities that were assumed to be lost.

Paradoxical and terminal lucidity are also very difficult to study. Not everyone with advanced dementia will experience episodes of lucidity before death. Lucid episodes are also unpredictable and typically occur without a particular trigger.

And as terminal lucidity can be a joyous time for those who witness the episode, it would be unethical for scientists to use that time to conduct their research. At the time of death, it’s also difficult for scientists to interview caregivers about any lucid moments that may have occurred.

Explanations for terminal lucidity extend beyond science. These moments of mental clarity may be a way for the dying person to say final goodbyes, gain closure before death, and reconnect with family and friends. Some believe episodes of terminal lucidity are representative of the person connecting with an afterlife.

Why is it important to know about terminal lucidity?

People can have a variety of reactions to seeing terminal lucidity in a person with advanced dementia. While some will experience it as being peaceful and bittersweet, others may find it deeply confusing and upsetting. There may also be an urge to modify care plans and request lifesaving measures for the dying person.

Being aware of terminal lucidity can help loved ones understand it is part of the dying process, acknowledge the person with dementia will not recover, and allow them to make the most of the time they have with the lucid person.

For those who witness it, terminal lucidity can be a final, precious opportunity to reconnect with the person that existed before dementia took hold and the “long goodbye” began.

Yen Ying Lim, Associate Professor, Turner Institute for Brain and Mental Health, Monash University and Diny Thomson, PhD (Clinical Neuropsychology) Candidate and Provisional Psychologist, Monash University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Don’t Forget…

Did you arrive here from our newsletter? Don’t forget to return to the email to continue learning!

Learn to Age Gracefully

Join the 98k+ American women taking control of their health & aging with our 100% free (and fun!) daily emails:

-

Caramelized Caraway Cabbage

10almonds is reader-supported. We may, at no cost to you, receive a portion of sales if you purchase a product through a link in this article.

Cabbage is an underrated vegetable for its many nutrients and its culinary potential—here’s a great way to make it a delectable starter or respectable side.

You will need

- 1 medium white cabbage, sliced into 1″ thick slabs

- 1 tbsp extra-virgin olive oil

- 1 tbsp caraway seeds

- 1 tsp black pepper

- ½ tsp turmeric

- ¼ tsp MSG or ½ tsp low-sodium salt

Method

(we suggest you read everything at least once before doing anything)

1) Preheat the oven to 400℉ / 200℃.

2) Combine the non-cabbage ingredients in a small bowl, whisking to mix thoroughly—with a tiny whisk if you have one, but a fork will work if necessary.

3) Arrange the cabbage slices on a lined baking tray and brush the seasoning-and-oil mixture over both sides of each slice.

4) Roast for 20–25 minutes until the cabbage is tender and beginning to caramelize.

5) Serve warm.

Enjoy!

Want to learn more?

For those interested in some of the science of what we have going on today:

- Curcumin (Turmeric) is worth its weight in gold

- Black Pepper’s Impressive Anti-Cancer Arsenal (And More)

- Avocado Oil vs Olive Oil – Which is Healthier?

Take care!

Don’t Forget…

Did you arrive here from our newsletter? Don’t forget to return to the email to continue learning!

Learn to Age Gracefully

Join the 98k+ American women taking control of their health & aging with our 100% free (and fun!) daily emails: