Stickers and wristbands aren’t a reliable way to prevent mosquito bites. Here’s why

10almonds is reader-supported. We may, at no cost to you, receive a portion of sales if you purchase a product through a link in this article.

Protecting yourself and family from mosquito bites can be challenging, especially in this hot and humid weather. Protests from young children and fears about topical insect repellents drive some to try alternatives such as wristbands, patches and stickers.

These products are sold online as well as in supermarkets, pharmacies and camping stores. They’re often marketed as providing “natural” protection from mosquitoes.

But unfortunately, they aren’t a reliable way to prevent mosquito bites. Here’s why – and what you can try instead.

Why is preventing mosquito bites important?

Mosquitoes can spread pathogens that make us sick. Japanese encephalitis and Murray Valley encephalitis viruses can have potentially fatal outcomes. While Ross River virus won’t kill you, it can cause potentially debilitating illnesses.

Health authorities recommend preventing mosquito bites by: avoiding areas and times of the day when mosquitoes are most active; covering up with long sleeved shirts, long pants, and covered shoes; and applying a topical insect repellent (a cream, lotion, or spray).

I don’t want to put sticky and smelly repellents on my skin!

While for many people, the “sting” of a biting mosquitoes is enough to prompt a dose of repellent, others are reluctant. Some are deterred by the unpleasant feel or smell of insect repellents. Others believe topical repellents contain chemicals that are dangerous to our health.

However, many studies have shown that, when used as recommended, these products are safe to use. All products marketed as mosquito repellents in Australia must be registered by the Australian Pesticides and Veterinary Medicines Authority; a process that provides recommendations for safe use.

How do topical repellents work?

While there remains some uncertainty about how the chemicals in topical insect repellents actually work, they appear to either block the sensory organs of mosquitoes that drive them to bite, or overpower the smells of our skin that helps mosquitoes find us.

Diethytolumide (DEET) is a widely recommended ingredient in topical repellents. Picaridin and oil of lemon eucalyptus are also used and have been shown to be effective and safe.

How do other products work?

“Physical” insect-repelling products, such as wristbands, coils and candles, often contain a botanically derived chemical and are often marketed as being an alternative to DEET.

However, studies have shown that devices such as candles containing citronella oil provide lower mosquito-bite prevention than topical repellents.

A laboratory study in 2011 found wristbands infused with peppermint oil failed to provide full protection from mosquito bites.

Even as topical repellent formulations applied to the skin, these botanically derived products have lower mosquito bite protection than recommended products such as those containing DEET, picaridin and oil of lemon eucalyptus.

Wristbands infused with DEET have shown mixed results but may provide some bite protection or bite reduction. DEET-based wristbands or patches are not currently available in Australia.

There is also a range of mosquito repellent coils, sticks, and other devices that release insecticides (for example, pyrethroids). These chemicals are primarily designed to kill or “knock down” mosquitoes rather than to simply keep them from biting us.

What about stickers and patches?

Although insect repellent patches and stickers have been available for many years, there has been a sudden surge in their marketing through social media. But there are very few scientific studies testing their efficacy.

Our current understanding of the way insect repellents work would suggest these small stickers and patches offer little protection from mosquito bites.

At best, they may reduce some bites in the way mosquito coils containing botanical products work. However, the passive release of chemicals from the patches and stickers is likely to be substantially lower than those from mosquito coils and other devices actively releasing chemicals.

One study in 2013 found a sticker infused with oil of lemon eucalyptus “did not provide significant protection to volunteers”.

Clothing impregnated with insecticides, such as permethrin, will assist in reducing mosquito bites but topical insect repellents are still recommended for exposed areas of skin.

Take care when using these products

The idea you can apply a sticker or patch to your clothing to protect you from mosquito bites may sound appealing, but these devices provide a false sense of security. There is no evidence they are an equally effective alternative to the topical repellents recommended by health authorities around the world. It only takes one bite from a mosquito to transmit the pathogens that result in serious disease.

It is also worth noting that there are some health warnings and recommendations for their use required by Australian Pesticides and Veterinary Medicines Authority. Some of these products warn against application to the skin (recommending application to clothing only) and to keep products “out of reach of children”. This is a challenge if attached to young children’s clothing.

Similar warnings are associated with most other topical and non-topical mosquito repellents. Always check the labels of these products for safe use recommendations.

Are there any other practical alternatives?

Topical insect repellents are safe and effective. Most can be used on children from 12 months of age and pose no health risks. Make sure you apply the repellent as a thin even coat on all exposed areas of skin.

But you don’t need “tropical strength” repellents for short periods of time outdoors; a range of formulations with lower concentrations of repellent will work well for shorter trips outdoors. There are some repellents that don’t smell as strong (for example, children’s formulations, odourless formulations) or formulations that may be more pleasant to use (for example, pump pack sprays).

Finally, you can always cover up. Loose-fitting long-sleeved shirts, long pants, and covered shoes will provide a physical barrier between you and mosquitoes on the hunt for your or your family’s blood this summer.

Cameron Webb, Clinical Associate Professor and Principal Hospital Scientist, University of Sydney

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Don’t Forget…

Did you arrive here from our newsletter? Don’t forget to return to the email to continue learning!

Recommended

Learn to Age Gracefully

Join the 98k+ American women taking control of their health & aging with our 100% free (and fun!) daily emails:

-

Grains: Bread Of Life, Or Cereal Killer?

10almonds is reader-supported. We may, at no cost to you, receive a portion of sales if you purchase a product through a link in this article.

Going Against The Grain?

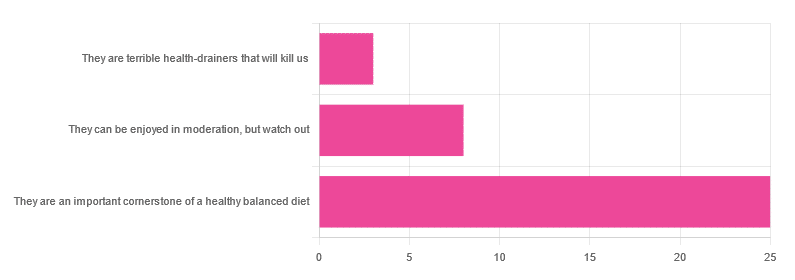

In Wednesday’s newsletter, we asked you for your health-related opinion of grains (aside from any gluten-specific concerns), and got the above-depicted, below-described, set of responses:

- About 69% said “They are an important cornerstone of a healthy balanced diet”

- About 22% said “They can be enjoyed in moderation, but watch out”

- About 8% said “They are terrible health-drainers that will kill us”

So, what does the science say?

They are terrible health-drainers that will kill us: True or False?

True or False depending on the manner of their consumption!

There is a big difference between the average pizza base and a bowl of oats, for instance. Or rather, there are a lot of differences, but what’s most critical here?

The key is: refined and ultraprocessed grains are so inferior to whole grains as to be actively negative for health in most cases for most people most of the time.

But! It’s not because processing is ontologically evil (in reality: some processed foods are healthy, and some unprocessed foods are poisonous). although it is a very good general rule of thumb.

So, we need to understand the “why” behind the “key” that we just gave above, and that’s mostly about the resultant glycemic index and associated metrics (glycemic load, insulin index, etc).

In the case of refined and ultraprocessed grains, our body gains sugar faster than it can process it, and stores it wherever and however it can, like someone who has just realised that they will be entertaining a houseguest in 10 minutes and must tidy up super-rapidly by hiding things wherever they’ll fit.

And when the body tries to do this with sugar from refined grains, the result is very bad for multiple organs (most notably the liver, but the pancreas takes quite a hit too) which in turn causes damage elsewhere in the body, not to mention that we now have urgently-produced fat stored in unfortunate places like our liver and abdominal cavity when it should have gone to subcutaneous fat stores instead.

In contrast, whole grains come with fiber that slows down the absorption of the sugars, such that the body can deal with them in an ideal fashion, which usually means:

- using them immediately, or

- storing them as muscle glycogen, or

- storing them as subcutaneous fat

👆 that’s an oversimplification, but we only have so much room here.

For more on this, see:

Glycemic Index vs Glycemic Load vs Insulin Index

And for why this matters, see:

Which Sugars Are Healthier, And Which Are Just The Same?

And for fixing it, see:

They can be enjoyed in moderation, but watch out: True or False?

Technically True but functionally False:

- Technically true: “in moderation” is doing a lot of heavy lifting here. One person’s “moderation” may be another person’s “abstemiousness” or “gluttony”.

- Functionally false: while of course extreme consumption of pretty much anything is going to be bad, unless you are Cereals Georg eating 10,000 cereals each day and being a statistical outlier, the issue is not the quantity so much as the quality.

Quality, we discussed above—and that is, as we say, paramount. As for quantity however, you might want to know a baseline for “getting enough”, so…

They are an important cornerstone of a healthy balanced diet: True or False?

True! This one’s quite straightforward.

3 servings (each being 90g, or about ½ cup) of whole grains per day is associated with a 22% reduction in risk of heart disease, 5% reduction in all-cause mortality, and a lot of benefits across a lot of disease risks:

❝This meta-analysis provides further evidence that whole grain intake is associated with a reduced risk of coronary heart disease, cardiovascular disease, and total cancer, and mortality from all causes, respiratory diseases, infectious diseases, diabetes, and all non-cardiovascular, non-cancer causes.

These findings support dietary guidelines that recommend increased intake of whole grain to reduce the risk of chronic diseases and premature mortality.❞

~ Dr. Dagfinn Aune et al.

We’d like to give a lot more sources for the same findings, as well as papers for all the individual claims, but frankly, there are so many that there isn’t room. Suffice it to say, this is neither controversial nor uncertain; these benefits are well-established.

Here’s a very informative pop-science article, that also covers some of the things we discussed earlier (it shows what happens during refinement of grains) before getting on to recommendations and more citations for claims than we can fit here:

Harvard School Of Public Health | Whole Grains

“That’s all great, but what if I am concerned about gluten?”

There certainly are reasons you might be, be it because of a sensitivity, allergy, or just because perhaps you’d like to know more.

Let’s first mention: not all grains contain gluten, so it’s perfectly possible to enjoy naturally gluten-free grains (such as oats and rice) as well as gluten-free pseudocereals, which are not actually grains but do the same job in culinary and nutritional terms (such as quinoa and buckwheat, despite the latter’s name).

Finally, if you’d like to know more about gluten’s health considerations, then check out our previous mythbusting special:

Enjoy!

Share This Post

-

Policosanol: A Rival To Statins, Without The Side Effects?

10almonds is reader-supported. We may, at no cost to you, receive a portion of sales if you purchase a product through a link in this article.

Policosanol (which can be extracted from various sources, but is mostly made from sugar cane extract) is marketed as lipid-lowering agent for improving cholesterol levels, but its research history has not been without controversy:

2001: it works!

After a lot of research in the 1990s, it came out of the gate strong in 2001, with:

❝Policosanol (5 and 10 mg/day) significantly decreased LDL-cholesterol (17.3% and 26.7%, respectively), total cholesterol (12.9% and 19.5%), as well as the ratios of LDL-cholesterol to high-density lipoprotein (HDL)-cholesterol (17.2% and 26.5%) and total cholesterol to HDL-cholesterol (16.3% and 21.0%) compared with baseline and placebo❞

This, by the way, is comparable in efficacy to the most powerful statins, but without the adverse side effects.

Source: Efficacy and tolerability of policosanol in hypercholesterolemic postmenopausal women

Furthermore, its effects were not limited to postmenopausal women, and additionally, it was found that 20mg/day was sufficient for optimal effects; 40mg worked exactly the same as 20mg:

2006–2010: we do not trust the Cubans!

After it had been marketed and used in much of the world for some years, extra scrutiny was brought upon it, because the initial studies had been performed by the same lab in Cuba, a commercial lab that had tested them for a private interest (i.e., a company selling the supplement):

Heart Beat: Policosanol: A sweet nothing for high cholesterol

And furthermore, US-based labs were unable to replicate the results:

Policosanols as Nutraceuticals: Fact or Fiction

The Cuban researchers countered that the composition of policosanol as produced in their lab was different than the composition of the policosanol as produced in the US labs, because of the purity of the ingredients used in the Cuban lab.

Which, on the face of it, could be true or could just be the claim of a commercial lab with an association with a company selling a product.

Of course, importing Cuban ingredients to test them in the US was not a reasonably accessible option for the US-based labs, because of the US’s embargo of Cuba. In principle it could be done, but unless there is already a huge clear profit incentive, research scientists are usually on their hands and knees begging for grants already, so getting extra funding for specially-important Cuban ingredients was not going to be likely.

2012: never mind, it does work after all!

An American meta-analysis of 4596 patients from 52 eligible studies (from around the world, so many of them not affected by the US’s embargo; some were from within the US using non-Cuban ingredients, though), found:

❝policosanol is more effective than plant sterols and stanols for LDL level reduction and more favorably alters the lipid profile, approaching antilipemic drug efficacy❞

Those last words there, to be clear, mean “yes, the original claim of being on a par with statins is at least more or less true”.

Source: Meta-Analysis of Natural Therapies for Hyperlipidemia: Plant Sterols and Stanols versus Policosanol

2018: also yes, the Cuban kind does get those extra-effective results, even when tested outside of Cuba

A Korean research team verified this; it’s quite straightforward so for brevity we’ll just drop links:

- Consumption of Cuban Policosanol Improves Blood Pressure and Lipid Profile via Enhancement of HDL Functionality in Healthy Women Subjects: Randomized, Double-Blinded, and Placebo-Controlled Study

- Long-Term Consumption of Cuban Policosanol Lowers Central and Brachial Blood Pressure and Improves Lipid Profile With Enhancement of Lipoprotein Properties in Healthy Korean Participants

Mystery resolved!

Want to try some?

We don’t sell it, but here for your convenience is an example product on Amazon—it’s not the Cuban kind, because the US’s trade embargo makes it difficult for the US to import even things that are theoretically now exempt from the embargo such as food and medicines. In principle they can now be imported, but in practice, the extra regulations added to Cuban imports make it nearly impossible, especially for small sellers.

Still, it’s 40mg/tablet policosanol from sugar cane extract, and 3rd party lab tested, so it’s the next best thing 😎

Enjoy!

Share This Post

-

Feel Great, Lose Weight – by Dr. Rangan Chatterjee

10almonds is reader-supported. We may, at no cost to you, receive a portion of sales if you purchase a product through a link in this article.

We all know that losing weight sustainably tends to be harder than simply losing weight. We know that weight loss needs to come with lifestyle change. But how to get there?

One of the biggest problems that we might face while trying to lose weight is that our “metabolic thermostat” has got stuck at the wrong place. Trying to move it just makes our bodies think we are starving, and everything gets even worse. We can’t even “mind over matter” our way through it with willpower, because our bodies will do impressive things on a cellular level in an attempt to save us… Things that are as extraordinary as they are extraordinarily unhelpful.

Dr. Rangan Chatterjee is here to help us cut through that.

In this book, he covers how our metabolic thermostat got stuck in the wrong place, and how to gently tease it back into a better position.

Some advices won’t be big surprises—go for a whole foods diet, avoiding processed food, for example. Probably not a shocker.

Others are counterintuitive, but he explains how they work—exercising less while moving more, for instance. Sounds crazy, but we assure you there’s a metabolic explanation for it that’s beyond the scope of this review. And there’s plenty more where that came from, too.

Bottom line: if your weight has been either slowly rising, or else very stable but at a higher point than you’d like, Dr. Chatterjee can help you move the bar back to where you want it—and keep it there.

Share This Post

Related Posts

-

Here’s how to help protect your family from norovirus

10almonds is reader-supported. We may, at no cost to you, receive a portion of sales if you purchase a product through a link in this article.

What you need to know

- Norovirus is a very contagious infection that causes vomiting and diarrhea.

- The best way to help protect against norovirus is to wash your hands often with soap and warm water, since hand sanitizer may not be effective at killing the virus.

- If someone in your household has symptoms of norovirus, isolate them away from others, watch for signs of dehydration, and take steps to help prevent it from spreading.

If you feel like everyone is sick right now, you’re not alone. Levels of respiratory illnesses like COVID-19, flu, and RSV remain remain high in many states, and the U.S. is also battling a wave of norovirus, one of several viruses that cause a very contagious infection of the stomach and intestines.

Although norovirus infections are more common during the colder months—it’s also called the “winter vomiting disease”—the virus can spread at any time. Right now, however, cases have more than doubled since last year’s peak.

Read on to learn about the symptoms of norovirus, how it spreads, and what to do if someone in your household gets sick.

What are the symptoms of norovirus?

Norovirus is a very contagious infection that causes vomiting and diarrhea, which typically begins 12 to 48 hours after exposure to the virus. Additional symptoms may include stomach pain, body aches, headaches, and a fever. Norovirus typically resolves within three days, but people who are infected may still be contagious for up to two days after symptoms resolve.

Norovirus may cause dehydration, or a dangerous loss of fluids, especially in young children and older adults. See a health care provider if you or someone in your household shows signs of dehydration, which may include decreased urination, dizziness, a dry mouth and throat, sleepiness, and crying without tears.

How can you help protect against norovirus?

You can get norovirus if you have close contact with someone who is infected, touch a contaminated surface and then touch your mouth or nose, or consume contaminated food or beverages.

The best way to help protect yourself and others against norovirus is to wash your hands often with soap and warm water, since hand sanitizer may not be effective at killing the virus. Other ways to help protect yourself may include cooking food thoroughly and washing fruits and vegetables before eating them.

You can get sick with norovirus even if you’ve had it before, since there are many different strains.

How can families help protect against the spread of norovirus at home?

If someone in your household has symptoms of norovirus, isolate them away from others and watch for signs of dehydration. If you are sick with norovirus, do not prepare food for others in your household and use a separate bathroom, if possible.

When cleaning up after someone who has norovirus, wear rubber, latex, or nitrile gloves. Then wash your hands thoroughly.

Clean surfaces using a solution containing five to 25 tablespoons of bleach (that’s 12.5 fluid ounces, or just over ¾ cup), per gallon of water. Leave the bleach-water mix on surfaces for at least five minutes before wiping it off.

For more information, talk to your health care provider.

This article first appeared on Public Good News and is republished here under a Creative Commons license.

Don’t Forget…

Did you arrive here from our newsletter? Don’t forget to return to the email to continue learning!

Learn to Age Gracefully

Join the 98k+ American women taking control of their health & aging with our 100% free (and fun!) daily emails:

-

Encyclopedia Of Herbal Medicine – by Andrew Chevallier

10almonds is reader-supported. We may, at no cost to you, receive a portion of sales if you purchase a product through a link in this article.

A common problem with a lot of herbal medicine is it’s “based on traditional use only”, while on the other hand, learning about the actual science of it can mean poring through stacks of Randomized Clinical Trials, half of which are paywalled.

This beautifully and clearly-illustrated book bridges that gap. It gives not just the history, but also the science, of the use of many medicinal herbs (spotlight on 100 key ones; details on 450 more).

It gives advice on growing, harvesting, processing, and using the herbs, as well as what not to do (with regard to safety). And in case you don’t fancy yourself a gardener, you’ll also find advice on places one can buy herbs, and what you’ll need to know to choose them well (controlling for quality etc).

You can read it cover-to-cover, or look up what you need by plant in its general index, or by ailment (200 common ailments listed). As for its bibliography, it does list many textbooks, but not individual papers—though it does cite 12 popular scientific journals too.

Bottom line: if you want a good, science-based, one-stop book for herbal medicine, this is a top-tier choice.

Click here to check out the Encyclopedia of Herbal Medicine, and expand your home remedy repertoire!

Don’t Forget…

Did you arrive here from our newsletter? Don’t forget to return to the email to continue learning!

Learn to Age Gracefully

Join the 98k+ American women taking control of their health & aging with our 100% free (and fun!) daily emails:

-

Protein: How Much Do We Need, Really?

10almonds is reader-supported. We may, at no cost to you, receive a portion of sales if you purchase a product through a link in this article.

Mythbusting Protein!

Yesterday, we asked you for your policy on protein consumption. The distribution of responses was as follows:

- A marginal majority (about 55%) voted for “Protein is very important, but we can eat too much of it”

- A large minority (about 35%) voted for “We need lots of protein; the more, the better!”

- A handful (about 4%) voted for “We should go as light on protein as possible”

- A handful (6%) voted for “If we don’t eat protein, our body will create it from other foods”

So, what does the science say?

If we don’t eat protein, our body will create it from other foods: True or False?

Contingently True on an absurd technicality, but for all practical purposes False.

Our body requires 20 amino acids (the building blocks of protein), 9 of which it can’t synthesize and absolutely must get from food. Normally, we get those amino acids from protein in our diet, and we can also supplement them by buying amino acid supplements.

Specifically, we require (per kg of bodyweight) a daily average of:

- Histidine: 10 mg

- Isoleucine: 20 mg

- Leucine: 39 mg

- Lysine: 30 mg

- Methionine: 10.4 mg

- Phenylalanine*: 25 mg

- Threonine: 15 mg

- Tryptophan: 4 mg

- Valine: 26 mg

*combined with the non-essential amino acid tyrosine

Source: Protein and Amino Acid Requirements In Human Nutrition: WHO Technical Report

However, to get the requisite amino acid amounts, without consuming actual protein, would require gargantuan amounts of supplementation (bearing in mind bioavailability will never be 100%, so you’ll always need to take more than it seems), using supplements that will have been made by breaking down proteins anyway.

So unless you live in a laboratory and have access to endless amounts of all of the required amino acids (you can’t miss even one; you will die), and are willing to do that for the sake of proving a point, then you do really need to eat protein.

Your body cannot, for example, simply break down sugar and use it to make the protein you need.

On another technical note… Do bear in mind that many foods that we don’t necessarily think of as being sources of protein, are sources of protein.

Grains and grain products, for example, all contain protein; we just don’t think of them as that because their macronutritional profile is heavily weighted towards carbohydrates.

For that matter, even celery contains protein. How much, you may ask? Almost none! But if something has DNA, it has protein. Which means all plants and animals (at least in their unrefined forms).

So again, to even try to live without protein would very much require living in a laboratory.

We can eat too much protein: True or False?

True. First on an easy technicality; anything in excess is toxic. Even water, or oxygen. But also, in practical terms, there is such a thing as too much protein. The bar is quite high, though:

❝Based on short-term nitrogen balance studies, the Recommended Dietary Allowance of protein for a healthy adult with minimal physical activity is currently 0.8 g protein per kg bodyweight per day❞

❝To meet the functional needs such as promoting skeletal-muscle protein accretion and physical strength, dietary intake of 1.0, 1.3, and 1.6 g protein per kg bodyweight per day is recommended for individuals with minimal, moderate, and intense physical activity, respectively❞

❝Long-term consumption of protein at 2 g per kg bodyweight per day is safe for healthy adults, and the tolerable upper limit is 3.5 g per kg bodyweight per day for well-adapted subjects❞

❝Chronic high protein intake (>2 g per kg bodyweight per day for adults) may result in digestive, renal, and vascular abnormalities and should be avoided❞

Source: Dietary protein intake and human health

To put this into perspective, if you weigh about 160lbs (about 72kg), this would mean eating more than 144g protein per day, which grabbing a calculator means about 560g of lean beef, or 20oz, or 1¼lb.

If you’re eating quarter-pounder burgers though, that’s not usually so lean, so you’d need to eat more than nine quarter-pounder burgers per day to get too much protein.

High protein intake damages the kidneys: True or False?

True if you have kidney damage already; False if you are healthy. See for example:

- Effects of dietary protein restriction on the progression of advanced renal disease in the modification of diet in renal disease study

- A high protein diet has no harmful effects: a one-year crossover study in healthy male athletes

High protein intake increases cancer risk: True or False?

True or False depending on the source of the protein, so functionally false:

- Eating protein from red meat sources has been associated with higher risk for many cancers

- Eating protein from other sources has been associated with lower risk for many cancers

Source: Red Meat Consumption and Mortality Results From 2 Prospective Cohort Studies

High protein intake increase risk of heart disease: True or False?

True or False depending on the source of the protein, so, functionally false:

- Eating protein from red meat sources has been associated with higher risk of heart disease

- Eating protein from other sources has been associated with lower risk of heart disease

Source: Major Dietary Protein Sources and Risk of Coronary Heart Disease in Women

In summary…

Getting a good amount of good quality protein is important to health.

One can get too much, but one would have to go to extremes to do so.

The source of protein matters:

- Red meat is associated with many health risks, but that’s not necessarily the protein’s fault.

- Getting plenty of protein from (ideally: unprocessed) sources such as poultry, fish, and/or plants, is critical to good health.

- Consuming “whole proteins” (that contain all 9 amino acids that we can’t synthesize) are best.

Learn more: Complete proteins vs. incomplete proteins (explanation and examples)

Don’t Forget…

Did you arrive here from our newsletter? Don’t forget to return to the email to continue learning!

Learn to Age Gracefully

Join the 98k+ American women taking control of their health & aging with our 100% free (and fun!) daily emails: