The Comfort Book – by Matt Haig

10almonds is reader-supported. We may, at no cost to you, receive a portion of sales if you purchase a product through a link in this article.

This book “is what it says on the tin”. Matt Haig, bestselling author of “Reasons to Stay Alive” (amongst other works) is here with “a hug in a book”.

The format of the book is an “open it at any page and you’ll find something of value” book. Its small chapters are sometimes a few pages long, but often just a page. Sometimes just a line. Always deep.

All of us, who live long enough, will ponder our mortality sometimes. The feelings we may have might vary on a range from “afraid of dying” to “despairing of living”… but Haig’s single biggest message is that life is full of wonder; each moment precious.

- That hope is an incredible (and renewable!) resource.

- That we are more than a bad week, or month, or year, or decade.

- That when things are taken from us, the things that remain have more value.

Bottom line: you might cry (this reviewer did!), but it’ll make your life the richer for it, and remind you—if ever you need it—the value of your amazing life.

Don’t Forget…

Did you arrive here from our newsletter? Don’t forget to return to the email to continue learning!

Recommended

Learn to Age Gracefully

Join the 98k+ American women taking control of their health & aging with our 100% free (and fun!) daily emails:

-

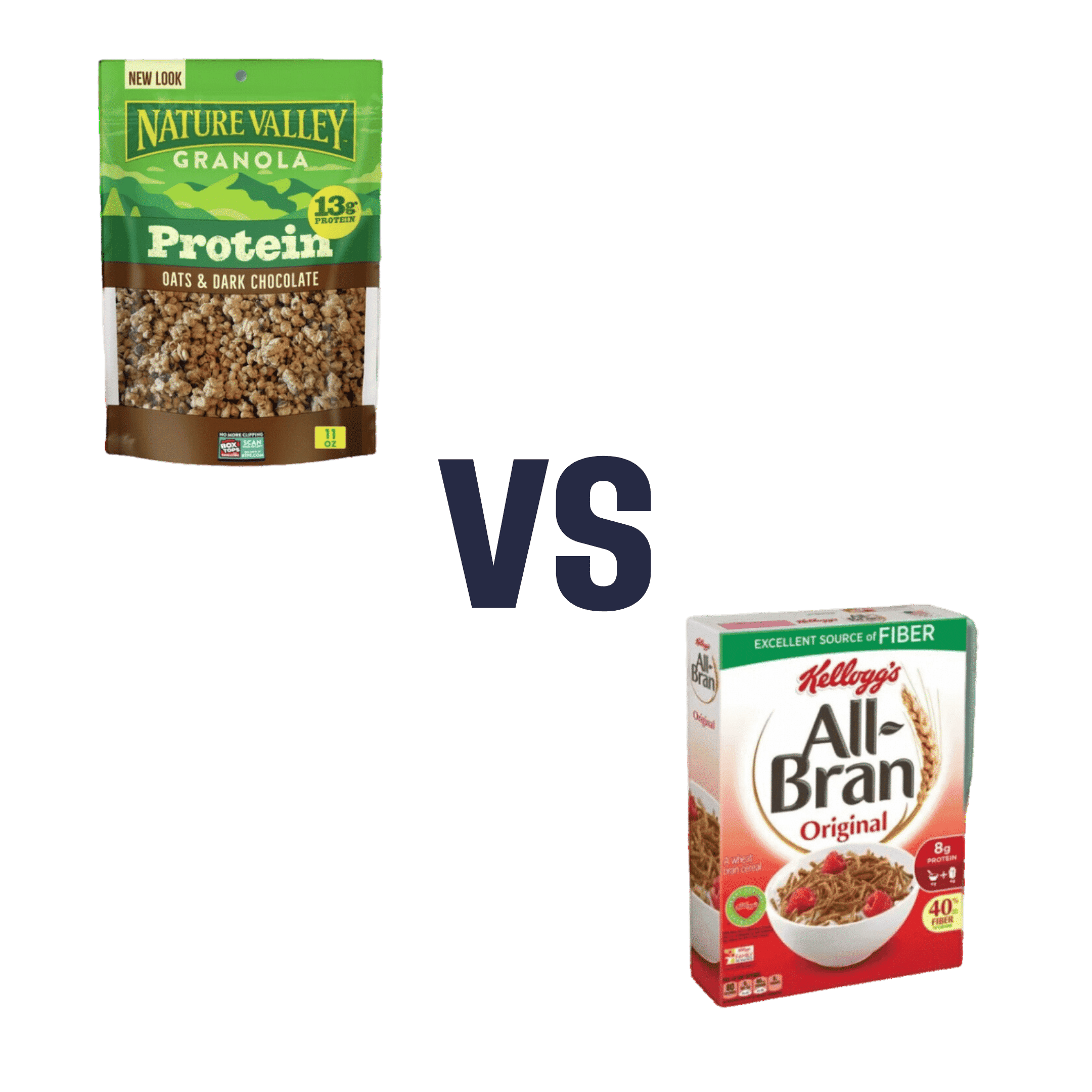

Nature Valley Protein Granola vs Kellog’s All-Bran – Which is Healthier?

10almonds is reader-supported. We may, at no cost to you, receive a portion of sales if you purchase a product through a link in this article.

Our Verdict

When comparing Nature Valley Protein Granola to Kellog’s All-Bran, we picked the All-Bran.

Why?

While the Protein Granola indeed contains more protein (13g/cup, compared to 5g/cup), it also contains three times as much sugar (18g/cup, compared to 9g/cup) and only ⅓ as much fiber (4g/cup, compared to 12g/cup)

Given that fiber is what helps our bodies to absorb sugar more gently (resulting in fewer spikes), this is extremely important, especially since 18g of sugar in one cup of Protein Granola is already most of the recommended daily allowance, all at once!

For reference: the AHA recommends no more than 25g added sugar for women, or 32g for men

Hence, we went for the option with 3x as much fiber and ⅓ of the sugar, the All-Bran.

For more about keeping blood sugars stable, see:

10 Ways To Balance Blood Sugars

Enjoy!

Share This Post

-

Blood-Brain Barrier Breach Blamed For Brain-Fog

10almonds is reader-supported. We may, at no cost to you, receive a portion of sales if you purchase a product through a link in this article.

Move Over, Leaky Gut. Now It’s A Leaky Brain.

…which is not a headline that promises good news, and indeed, the only good news about this currently is “now we know another thing that’s happening, and thus can work towards a treatment for it”.

Back in February (most popular media outlets did not rush to publish this, as it rather goes against the narrative of “remember when COVID was a thing?” as though the numbers haven’t risen since the state of emergency was declared over), a team of Irish researchers made a discovery:

❝For the first time, we have been able to show that leaky blood vessels in the human brain, in tandem with a hyperactive immune system may be the key drivers of brain fog associated with long covid❞

~ Dr. Matthew Campbell (one of the researchers)

Let’s break that down a little, borrowing some context from the paper itself:

- the leaky blood vessels are breaching the blood-brain-barrier

- that’s a big deal, because that barrier is our only filter between our brain and Things That Definitely Should Not Go In The Brain™

- a hyperactive immune system can also be described as chronic inflammation

- in this case, that includes chronic neuroinflammation which, yes, is also a major driver of dementia

You may be wondering what COVID has to do with this, and well:

- these blood-brain-barrier breaches were very significantly associated (in lay terms: correlated, but correlated is only really used as an absolute in write-ups) with either acute COVID infection, or Long Covid.

- checking this in vitro, exposure of brain endothelial cells to serum from patients with Long Covid induced the same expression of inflammatory markers.

How important is this?

As another researcher (not to mention: professor of neurology and head of the school of medicine at Trinity) put it:

❝The findings will now likely change the landscape of how we understand and treat post-viral neurological conditions.

It also confirms that the neurological symptoms of long covid are measurable with real and demonstrable metabolic and vascular changes in the brain.❞

~ Dr. Colin Doherty (see mini-bio above)

You can read a pop-science article about this here:

Irish researchers discover underlying cause of “brain fog” linked with long covid

…and you can read the paper in full here:

Want to stay safe?

Beyond the obvious “get protected when offered boosters/updates” (see also: The Truth About Vaccines), other good practices include the same things most people were doing when the pandemic was big news, especially avoiding enclosed densely-populated places, washing hands frequently, and looking after your immune system. For that latter, see also:

Beyond Supplements: The Real Immune-Boosters!

Take care!

Share This Post

- the leaky blood vessels are breaching the blood-brain-barrier

-

The Best Foods For Collagen Production

10almonds is reader-supported. We may, at no cost to you, receive a portion of sales if you purchase a product through a link in this article.

Dr. Andrea Suarez gives us the low-down on collagen synthesis and maintenance. Collagen is the most abundant protein in our body, and it can be fairly described as “the stuff that holds us together”. It’s particularly important for joints and bones too, though many people’s focus on it is for the skin. Whatever your priorities, collagen levels are something it pays to be mindful of, as they usually drop quite sharply after a certain age. What certain age? Well, that depends a lot on you, and your diet and lifestyle. But it can start to decline from the age of 30 with often noticeable drop-offs in one’s mid-40s and again in one’s mid-60s.

Showing us what we’re made of

There’s a lot more to having good collagen levels than just how much collagen we consume (which for vegetarians/vegans, will be “none”, unless using the “except if for medical reasons” exemption, which is probably a little tenuous in the case of collagen but nevertheless it’s a possibility; this exemption is usually one that people use for, say, a nasal spray vaccine that contains gelatine, or a medicinal tablet that contains lactose, etc).

Rather, having good collagen levels is also a matter of what we eat that allows us to synthesize our own collagen (which includes: its ingredients, and various “helper” nutrients), as well as what dietary adjustments we make to avoid our extant collagen getting broken down, degraded, and generally lost.

Here’s what Dr. Suarez recommends:

Protein-rich foods (but watch out)

- Protein is essential for collagen production.

- Sources: fish, soy, lean meats (but not red meats, which—counterintuitively—degrade collagen), eggs, lentils.

- Egg whites are high in lysine, vital for collagen synthesis.

- Bone broth is a natural source of collagen.

Omega-3 fatty acids

- Omega-3s are anti-inflammatory and protect skin collagen.

- Sources: walnuts, chia seeds, flax seeds, fatty fish (e.g. mackerel, sardines).

Leafy greens

- Leafy dark green vegetables (e.g. kale, spinach) are rich in vitamins C and B9.

- Vitamin C is crucial for collagen synthesis and acts as an antioxidant.

- Vitamin B9 supports skin cell division and DNA repair.

Red fruits & vegetables

- Red fruits/vegetables (e.g. tomatoes, red bell peppers) contain lycopene, an antioxidant that protects collagen from UV damage (so, that aspect is mostly relevant for skin, but antioxidants are good things to have in all of the body in any case).

Orange-colored vegetables

- Carrots and sweet potatoes are rich in vitamin A, which helps in collagen repair and synthesis.

- Vitamin A is best from food, not supplements, to avoid potential toxicity.

Fruits rich in vitamin C

- Citrus fruits, kiwi, and berries are loaded with vitamin C and antioxidants, essential for collagen synthesis and skin health.

Soy

- Soy products (e.g. tofu, soybeans) contain isoflavones, which reduce inflammation and inhibit enzymes that degrade collagen.

- Soy is associated with lower risks of chronic diseases.

Garlic

- Garlic contains sulfur, taurine, and lipoic acid, important for collagen production and repair.

What to avoid:

- Reduce foods high in advanced glycation end products (AGEs), which damage collagen and promote inflammation.

- AGEs are found in fried, roasted, or grilled fatty proteinous foods (e.g. meat, including synthetic meat, and yes, including grass-fed nicely marketed meat—although processed meat such as bacon and sausages are even worse than steaks etc).

- Switch to cooking methods like boiling or steaming to reduce AGE levels.

- Processed foods, sugary pastries, and red meats contribute to collagen degradation.

General diet tips:

- Incorporate more plant-based, antioxidant-rich foods.

- Opt for slow cooking to reduce AGEs.

- Since sustainability is key, choose foods you enjoy for a collagen-boosting diet that you won’t seem like a chore a month later.

For more on all of this, enjoy:

Click Here If The Embedded Video Doesn’t Load Automatically!

Want to learn more?

You might also like to read:

We Are Such Stuff As Fish Are Made Of ← our main feature research review about collagen

Take care!

Share This Post

Related Posts

-

Safe Effective Sleep Aids For Seniors

10almonds is reader-supported. We may, at no cost to you, receive a portion of sales if you purchase a product through a link in this article.

Safe Efective Sleep Aids For Seniors

Choosing a safe, effective sleep aid can be difficult, especially as we get older. Take for example this research review, which practically says, when it comes to drugs, “Nope nope nope nope nope, definitely not, we don’t know, wow no, useful in one (1) circumstance only, definitely not, fine if you must”:

Review of Safety and Efficacy of Sleep Medicines in Older Adults

Let’s break it down…

What’s not so great

Tranquilizers aren’t very healthy ways to get to sleep, and are generally only well-used as a last resort. The most common of these are benzodiazepines, which is the general family of drugs with names usually ending in –azepam and –azolam.

Their downsides are many, but perhaps their biggest is their tendency to induce tolerance, dependence, and addiction.

Non-benzo hypnotics aren’t fabulous either. Z-drugs such as zolpidem tartrate (popularly known by the brand name Ambien, amongst others), comes with warnings that it shouldn’t be prescribed if you have sleep apnea (i.e., one of the most common causes of insomnia), and should be used only with caution in patients who have depression or are elderly, as it may cause protracted daytime sedation and/or ataxia.

See also: Benzodiazepine and z-drug withdrawal

(and here’s a user-friendly US-based resource for benzodiazepine addiction specifically)

Antihistamines are commonly sold as over-the-counter sleep aids, because they can cause drowsiness, but a) they often don’t b) they may reduce your immune response that you may actually need for something. They’re still a lot safer than tranquilizers, though.

What about cannabis products?

We wrote about some of the myths and realities of cannabis use yesterday, but it does have some medical uses beyond pain relief, and use as a sleep aid is one of them—but there’s another caveat.

How it works: CBD, and especially THC, reduces REM sleep, causing you to spend longer in deep sleep. Deep sleep is more restorative and restful. And, if part of your sleep problem was nightmares, they can only occur during REM sleep, so you’ll be skipping those, too. However, REM sleep is also necessary for good brain health, and missing too much of it will result in cognitive impairment.

Opting for a CBD product that doesn’t contain THC may improve sleep with less (in fact, no known) risk of long-term impairment.

See: Cannabis, Cannabinoids, and Sleep: a Review of the Literature

Melatonin: a powerful helper with a good safety profile

We did a main feature on this recently, so we won’t take up too much space here, but suffice it to say: melatonin is our body’s own natural sleep hormone, and our body is good at scrubbing it when we see white/blue light (so, look at such if you feel groggy upon awakening, and it should clear up quickly), so that and its very short elimination half-life again make it quite safe.

Unlike tranquilizers, we don’t develop a tolerance to it, let alone dependence or addiction, and unlike cannabis, it doesn’t produce long-term adverse effects (after all, our brains are supposed to have melatonin in them every night). You can read our previous main feature (including a link to get melatonin, if you want) here:

Melatonin: A Safe Natural Sleep Supplement

Herbal options: which really work?

Valerian? Probably not, but it seems safe to try. Data on this is very inconsistent, and many studies supporting it had poor methodology. Shinjyo et al. also hypothesized that the inconsistency may be due to the highly variable quality of the supplements, and lack of regulation, as they are provided “based on traditional use only”.

Chamomile? Given the fame of chamomile tea as a soothing, relaxing bedtime drink, there’s surprisingly little research out there for this specifically (as opposed to other medicinal features of chamomile, of which there are plenty).

But here’s one study that found it helped significantly:

The effects of chamomile extract on sleep quality among elderly people: A clinical trial

Unlike valerian, which is often sold as tablets, chamomile is most often sold as a herbal preparation for making chamomile tea, so the quality is probably quite consistent. You can also easily grow your own in most places!

Technological interventions

We may not have sci-fi style regeneration alcoves just yet, but white noise machines, or better yet, pink noise machines, help:

White Noise Is Good; Pink Noise Is Better

Note: the noise machine can be a literal physical device purchased to do that (most often sold as for babies, but babies aren’t the only ones who need to sleep!), but it can also just be your phone playing an appropriate audio file (there are apps available) or YouTube video.

We reviewed some sleep apps; you might like those too:

The Head-To-Head Of Google and Apple’s Top Apps For Getting Your Head Down

Enjoy, and rest well!

Don’t Forget…

Did you arrive here from our newsletter? Don’t forget to return to the email to continue learning!

Learn to Age Gracefully

Join the 98k+ American women taking control of their health & aging with our 100% free (and fun!) daily emails:

-

Simple, 10-Minute Hip Opening Routine

10almonds is reader-supported. We may, at no cost to you, receive a portion of sales if you purchase a product through a link in this article.

Hips Feeling Stiff?

If so, Flow with Adee’s video (below) has just the solution with a quick 10-minute hip-opening routine. Designed for intermediates but open to all, we love Adee’s work and recommend that you reach out to her to tell her what you’d like to see next.

Other Methods

If you’re a book lover, we’ve reviewed a fantastic book on reducing hip pain. Alternatively, learn stretching from a ballerina with Jasmine McDonald’s ballet stretching routine.

Otherwise, enjoy today’s video:

How was the video? If you’ve discovered any great videos yourself that you’d like to share with fellow 10almonds readers, then please do email them to us!

Don’t Forget…

Did you arrive here from our newsletter? Don’t forget to return to the email to continue learning!

Learn to Age Gracefully

Join the 98k+ American women taking control of their health & aging with our 100% free (and fun!) daily emails:

-

The Simple Six – by Clinton Dobbins

10almonds is reader-supported. We may, at no cost to you, receive a portion of sales if you purchase a product through a link in this article.

We at 10almonds don’t believe in keeping things a mystery, so…

“The Simple Six” are:

- the squat

- the goblet squat

- the hinge

- the kettlebell swing

- the push

- the push-up

- the kettle-bell press

- the pull

- the chin-up

- the gait, and

- walking.

Ok, we’re being a little glib here because to be fair, those are chunked into six groups, but the point is: don’t let the title fool you into thinking the book could have been an article; there’s plenty of valuable content here.

That said, it is a short book (64 pages), but with an average of 10 pages per exercise type, it’s a lot more than for example we could ever put into our newsletter.

Bottom line: we know that 10almonds readers like simple, clear, evidence-based, to-the-point health information, and that’s what this book is, so we do recommend it.

Click here to check out The Simple Six, and streamline your workouts!

Don’t Forget…

Did you arrive here from our newsletter? Don’t forget to return to the email to continue learning!

Learn to Age Gracefully

Join the 98k+ American women taking control of their health & aging with our 100% free (and fun!) daily emails: