The Conquest of Happiness – by Bertrand Russell

10almonds is reader-supported. We may, at no cost to you, receive a portion of sales if you purchase a product through a link in this article.

When we have all our physical needs taken care of, why are we often still not happy, and what can we do about that?

Mathematician, philosopher, and Nobel prizewinner Bertrand Russell has answers. And, unlike many of “the great philosophers”, his writing style is very clear and accessible.

His ideas are simple and practical, yet practised by few. Rather than taking a “be happy with whatever you have” approach, he does argue that we should strive to find more happiness in some areas and ways—and lays out guidelines for doing so.

Areas to expand, areas to pull back on, areas to walk a “virtuous mean”. Things to be optimistic about; things to not get our hopes up about.

Applying Russell’s model, there’s no more “should I…?” moments of wondering which way to jump.

Bottom line: if you’ve heard enough about “how to be happy” from wishy-washier sources, you might find the work of this famous logician refreshing.

Click here to check out The Conquest of Happiness, and see how much happier you might become!

Don’t Forget…

Did you arrive here from our newsletter? Don’t forget to return to the email to continue learning!

Recommended

Learn to Age Gracefully

Join the 98k+ American women taking control of their health & aging with our 100% free (and fun!) daily emails:

-

Mythbusting Cookware Materials

10almonds is reader-supported. We may, at no cost to you, receive a portion of sales if you purchase a product through a link in this article.

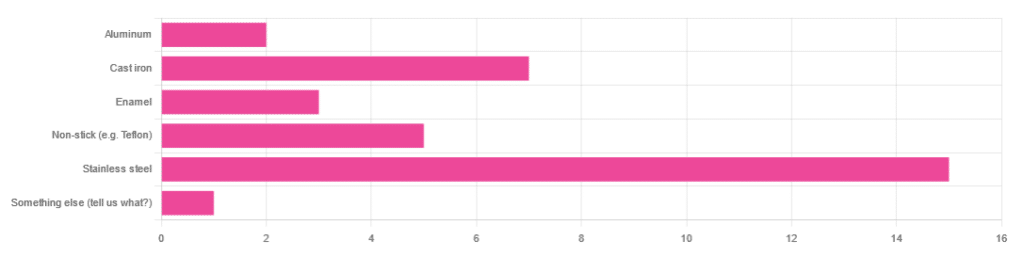

In Wednesday’s newsletter, we asked you what kind of cookware you mostly use, and got the above-depicted, below-described, set of responses:

- About 45% said stainless steel

- About 21% said cast iron

- About 15% said non-stick (e.g. Teflon)

- About 9% said enamel

- About 6% said aluminum

- And 1 person selected “something else”, but then commented to the contrary, writing “I use all of the above”

So, what does the science say about these options?

Stainless steel cookware is safe: True or False?

True! Assuming good quality and normal use, anyway. There really isn’t a lot to say about this, because it’s very unexciting. So long as it is what it is labelled as: there’s nothing coating it, nothing comes out of it unless you go to extremes*, and it’s easy to clean.

*If you cook for long durations at very high temperatures, it can leach nickel and chromium into food. What this means in practical terms: if you are using stainless steel to do deep-frying, then maybe stop that, and also consider going easy on deep-frying in general anyway, because obviously deep-frying is unhealthy for other reasons.

Per normal use, however: pretty much the only way (good quality) stainless steel cookware will harm you is if you touch it while it’s hot, or if it falls off a shelf onto your head.

That said, do watch out for cheap stainless steel cookware that can contain a lot of impurities, including heavy metals. Since you probably don’t have a mass spectrometer and/or chemistry lab at home to check for those impurities, your best guard here is simply to buy from a reputable brand with credible certifications.

Ceramic cookware is safe: True or False?

True… Most of the time! Ceramic pans usually have metal parts and a ceramic cooking surface coated with a very thin layer of silicon. Those metal parts will be as safe as the metals used, so if that’s stainless steel, you’re just as safe as the above. As for the silicon, it is famously inert and body-safe (which is why it’s used in body implants).

However: ceramic cookware that doesn’t have an obvious metal part and is marketed as being pure ceramic, will generally be sealed with some kind of glaze that can leach heavy metals contaminants into the food; here’s an example:

Lead toxicity from glazed ceramic cookware

Copper cookware is safe: True or False?

False! This is one we forgot to mention in the poll, as one doesn’t see a lot of it nowadays. The copper from copper pans can leach into food. Now, of course copper is an important mineral that we must get from our diet, but the amount of copper that that can leach into food from copper pans is far too much, and can induce copper toxicity.

In addition, copper cookware has been found to be, on average, highly contaminated with lead:

Non-stick cookware contaminates the food with microplastics: True or False?

True! If we were to discuss all the common non-stick contaminants here, this email would no longer fit (there’s a size limit before it gets clipped by most email services).

Suffice it to say: the non-stick coating, polytetrafluoroethylene, is itself a PFAS, that is to say, part of the category of chemicals considered environmental pollutants, and associated with a long list of health issues in humans (wherein the level of PFAS in our bloodstream is associated with higher incidence of many illnesses):

You may have noticed, of course, that the “non-stick” coating doesn’t stick very well to the pan, either, and will tend to come off over time, even if used carefully.

Also, any kind of wet cooking (e.g. saucepans, skillets, rice cooker inserts) will leach PFAS into the food. In contrast, a non-stick baking tray lined with baking paper (thus: a barrier between the tray and your food) is really not such an issue.

We wrote about PFAS before, so if you’d like a more readable pop-science article than the scientific paper above, then check out:

PFAS Exposure & Cancer: The Numbers Are High

Aluminum cookware contaminates the food with aluminum: True or False?

True! But not usually in sufficient quantities to induce aluminum toxicity, unless you are aluminum pans Georg who eats half a gram of aluminum per day, who is a statistical outlier and should not be counted.

That’s a silly example, but an actual number; the dose required for aluminum toxicity in blood is 100mg/L, and you have about 5 liters of blood.

Unless you are on kidney dialysis (because 95% of aluminum is excreted by the kidneys, and kidney dialysis solution can itself contain aluminum), you will excrete aluminum a lot faster than you can possibly absorb it from cookware. On the other hand, you can get too much of it from it being a permitted additive in foods and medications, for example if you are taking antacids they often have a lot of aluminum oxide in them—but that is outside the scope of today’s article.

However, aluminum may not be the real problem in aluminum pans:

❝In addition, aluminum (3.2 ± 0.25 to 4.64 ± 0.20 g/kg) and copper cookware (2.90 ± 0.12 g/kg) were highly contaminated with lead.

The time and pH-dependent study revealed that leaching of metals (Al, Pb, Ni, Cr, Cd, Cu, and Fe, etc.) into food was predominantly from anodized and non-anodized aluminum cookware.

More metal leaching was observed from new aluminum cookware compared to old. Acidic food was found to cause more metals to leach during cooking.❞

~ the same paper we cited when talking about copper

Cast iron cookware contaminates the food with iron: True or False?

True, but unlike with the other metals discussed, this is purely a positive, and indeed, it’s even recommended as a good way to fortify one’s diet with iron:

The only notable counterpoint we could find for this is if you have hemochromatosis, a disorder in which the body is too good at absorbing iron and holding onto it.

Thinking of getting some new cookware?

Here are some example products of high-quality safe materials on Amazon, but of course feel free to shop around:

Stainless Steel | Ceramic* | Cast Iron

*it says “non-stick” in the description, but don’t worry, it’s ceramic, not Teflon etc, and is safe

Bonus: rice cooker with stainless steel inner pot

Take care!

Share This Post

-

Horse Sedative Use Among Humans Spreads in Deadly Mixture of ‘Tranq’ and Fentanyl

10almonds is reader-supported. We may, at no cost to you, receive a portion of sales if you purchase a product through a link in this article.

TREASURE ISLAND, Fla. — Andrew McClave Jr. loved to lift weights. The 6-foot-4-inch bartender resembled a bodybuilder and once posed for a photo flexing his muscles with former pro wrestler Hulk Hogan.

“He was extremely dedicated to it,” said his father, Andrew McClave Sr., “to the point where it was almost like he missed his medication if he didn’t go.”

But the hobby took its toll. According to a police report, a friend told the Treasure Island Police Department that McClave, 36, suffered from back problems and took unprescribed pills to reduce the pain.

In late 2022, the friend discovered McClave in bed. He had no pulse. A medical examiner determined he had a fatal amount of fentanyl, cocaine, and xylazine, a veterinary tranquilizer used to sedate horses, in his system, an autopsy report said. Heart disease was listed as a contributing factor.

McClave is among more than 260 people across Florida who died in one year from accidental overdoses involving xylazine, according to a Tampa Bay Times analysis of medical examiner data from 2022, the first year state officials began tracking the substance. Numbers for 2023 haven’t been published.

The death toll reflects xylazine’s spread into the nation’s illicit drug supply. Federal regulators approved the tranquilizer for animals in the early 1970s and it’s used to sedate horses for procedures like oral exams and colic treatment, said Todd Holbrook, an equine medicine specialist at the University of Florida. Reports of people using xylazine emerged in Philadelphia, then the drug spread south and west.

What’s not clear is exactly what role the sedative plays in overdose deaths, because the Florida data shows no one fatally overdosed on xylazine alone. The painkiller fentanyl was partly to blame in all but two cases in which the veterinary drug was included as a cause of death, according to the Times analysis. Cocaine or alcohol played roles in the cases in which fentanyl was not involved.

Fentanyl is generally the “800-pound gorilla,” according to Lewis Nelson, chair of the emergency medicine department at Rutgers New Jersey Medical School, and xylazine may increase the risk of overdose, though not substantially.

But xylazine appears to complicate the response to opioid overdoses when they do happen and makes it harder to save people. Xylazine can slow breathing to dangerous levels, according to federal health officials, and it doesn’t respond to the overdose reversal drug naloxone, often known by the brand name Narcan. Part of the problem is that many people may not know they are taking the horse tranquilizer when they use other drugs, so they aren’t aware of the additional risks.

Lawmakers in Tallahassee made xylazine a Schedule 1 drug like heroin or ecstasy in 2016, and several other states including Pennsylvania, Ohio, and West Virginia have taken action to classify it as a scheduled substance, too. But it’s not prohibited at the federal level. Legislation pending in Congress would criminalize illicit xylazine use nationwide.

The White House in April designated the combination of fentanyl and xylazine, often called “tranq dope,” as an emerging drug threat. A study of 20 states and Washington, D.C., found that overdose deaths attributed to both illicit fentanyl and xylazine exploded from January 2019 to June 2022, jumping from 12 a month to 188.

“We really need to continue to be proactive,” said Amanda Bonham-Lovett, program director of a syringe exchange in St. Petersburg, “and not wait until this is a bigger issue.”

‘A Good Business Model’

There are few definitive answers about why xylazine use has spread — and its impact on people who consume it.

The U.S. Drug Enforcement Administration in September said the tranquilizer is entering the country in several ways, including from China and in fentanyl brought across the southwestern border. The Florida attorney general’s office is prosecuting an Orange County drug trafficking case that involves xylazine from a New Jersey supplier.

Bonham-Lovett, who runs IDEA Exchange Pinellas, the county’s anonymous needle exchange, said some local residents who use drugs are not seeking out xylazine — and don’t know they’re consuming it.

One theory is that dealers are mixing xylazine into fentanyl because it’s cheap and also affects the brain, Nelson said.

“It’s conceivable that if you add a psychoactive agent to the fentanyl, you can put less fentanyl in and still get the same kick,” he said. “It’s a good business model.”

In Florida, men accounted for three-quarters of fatal overdoses involving xylazine, according to the Times analysis. Almost 80% of those who died were white. The median age was 42.

Counties on Florida’s eastern coast saw the highest death tolls. Duval County topped the list with 46 overdoses. Tampa Bay recorded 19 fatalities.

Cocaine was also a cause in more than 80 cases, including McClave’s, the Times found. The DEA in 2018 warned of cocaine laced with fentanyl in Florida.

In McClave’s case, Treasure Island police found what appeared to be marijuana and a small plastic bag with white residue in his room, according to a police report. His family still questions how he took the powerful drugs and is grappling with his death.

He was an avid fisherman, catching snook and grouper in the Gulf of Mexico, said his sister, Ashley McClave. He dreamed of being a charter boat captain.

“I feel like I’ve lost everything,” his sister said. “My son won’t be able to learn how to fish from his uncle.”

Mysterious Wounds

Another vexing challenge for health officials is the link between chronic xylazine use and open wounds.

The wounds are showing up across Tampa Bay, needle exchange leaders said. The telltale sign is blackened, crusty tissue, Bonham-Lovett said. Though the injuries may start small — the size of a dime — they can grow and “take over someone’s whole limb,” she said.

Even those who snort fentanyl, instead of injecting it, can develop them. The phenomenon is unexplained, Nelson said, and is not seen in animals.

IDEA Exchange Pinellas has recorded at least 10 cases since opening last February, Bonham-Lovett said, and has a successful treatment plan. Staffers wash the wounds with soap and water, then dress them.

One person required hospitalization partly due to xylazine’s effects, Bonham-Lovett said. A 31-year-old St. Petersburg woman, who asked not to be named due to concerns over her safety and the stigma of drug use, said she was admitted to St. Anthony’s Hospital in 2023. The woman, who said she uses fentanyl daily, had a years-long staph infection resistant to some antibiotics, and a wound recently spread across half her thigh.

The woman hadn’t heard of xylazine until IDEA Exchange Pinellas told her about the drug. She’s thankful she found out in time to get care.

“I probably would have lost my leg,” she said.

This article was produced in partnership with the Tampa Bay Times.

KFF Health News is a national newsroom that produces in-depth journalism about health issues and is one of the core operating programs at KFF—an independent source of health policy research, polling, and journalism. Learn more about KFF.

Subscribe to KFF Health News’ free Morning Briefing.

Share This Post

-

Mindfulness – by Olivia Telford

10almonds is reader-supported. We may, at no cost to you, receive a portion of sales if you purchase a product through a link in this article.

Olivia Telford takes us on a tour of mindfulness, meditation, mindfulness meditation, and how each of these things impacts stress, anxiety, and depression—as well as less obvious things too, like productivity and relationships.

In the category of how much this is a “how-to-” guide… It’s quite a “how-to” guide. We’re taught how to meditate, we’re taught assorted mindfulness exercises, and we’re taught specific mindfulness interventions such as beating various life traps (e.g. procrastination, executive dysfunction, etc) with mindfulness.

The writing style is simple and to the point, explanatory and very readable. References are made to pop-science and hard science alike, and all in all, is not too far from the kind of writing you might expect to find here at 10almonds.

Bottom line: if you’d like to practice mindfulness meditation and want an easy “in”, or perhaps you’re curious and wonder what mindfulness could tangibly do for you and how, then this book is a great choice for that.

Click here to check out Mindfulness, and enjoy being more present in life!

Share This Post

Related Posts

-

Lower Cholesterol Naturally

10almonds is reader-supported. We may, at no cost to you, receive a portion of sales if you purchase a product through a link in this article.

Lower Cholesterol, Without Statins

We’ll start this off by saying that lowering cholesterol might not, in fact, be critical or even especially helpful for everyone, especially in the case of women. We covered this more in our article about statins:

…which was largely informed by the wealth of data in this book:

The Truth About Statins – by Dr. Barbara H. Roberts

…which in turn, may in fact put a lot of people off statins. We’re not here to tell you don’t use them—they may indeed be useful or even critical for some people, as Dr. Roberts herself also makes makes clear. But rather, we always recommend learning as much as possible about what’s going on, to be able to make the most informed choices when it comes to what often might be literally life-and-death decisions.

On which note, if anyone would like a quick refresher on cholesterol, what it actually is (in its various forms) and what it does, why we need it, the problems it can cause anyway, then here you go:

Now, with all that in mind, we’re going to assume that you, dear reader, would like to know:

- how to lower your LDL cholesterol, and/or

- how to maintain a safe LDL cholesterol level

Because, while the jury’s out on the dangers of high LDL levels for women in particular, it’s clear that for pretty much everyone, maintaining them within well-established safe zones won’t hurt.

Here’s how:

Relax

Or rather, manage your stress. This doesn’t just reduce your acute risk of a heart attack, it also improves your blood metrics along the way, and yes, that includes not just blood pressure and blood sugars, but even triglycerides! Here’s the science for that, complete with numbers:

What are the effects of psychological stress and physical work on blood lipid profiles?

With that in mind, here’s…

How To Manage Chronic Stress (Even While Chronically Stressed)

Not chemically “relaxed”, though

While relaxing is important, drinking alcohol and smoking are unequivocally bad for pretty much everything, and this includes cholesterol levels:

Can We Drink To Good Health? ← this also covers popular beliefs about red wine and heart health, and the answer is no, we cannot

As for smoking, it is good to quit as soon as possible, unless your doctor specifically advises you otherwise (there are occasional situations where something else needs to be dealt with first, but not as many some might like to believe):

Addiction Myths That Are Hard To Quit

If you’re wondering about cannabis (CBD and/or THC), then we’d love to tell you about the effect these things have on heart health in general and cholesterol levels in particular, but the science is far too young (mostly because of the historic, and in some places contemporary, illegality cramping the research), and we could only find small, dubious, mutually contradictory studies so far. So the honest answer is: science doesn’t know this one, yet.

Exercise… But don’t worry, you can still stay relaxed

When it comes to heart health, the most important thing is keeping moving, so getting in those famous 150 minutes per week of moderate exercise is critical, and getting more is ideal.

240 minutes per week is a neat 40 minutes per day, by the way and is very attainable (this writer lives a 20-minute walk away from where she does her daily grocery shopping, thus making for a daily 40-minute round trip, not counting the actual shopping).

See: The Doctor Who Wants Us To Exercise Less, And Move More

If walking is for some reason not practical for you, here’s a whole list of fun options that don’t feel like exercise but are:

Manage your hormones

This one is mostly for menopausal women, though some people with atypical hormonal situations may find it applicable too.

Estrogen protects the heart… Until it doesn’t:

See also: World Menopause Day: Menopause & Cardiovascular Disease Risk

Here’s a great introduction to sorting it out, if necessary:

Dr. Jen Gunter: What You Should Have Been Told About Menopause Beforehand

Eat a heart-healthy diet

Shocking nobody, but it has to be said, for the sake of being methodical. So, what does that look like?

What Matters Most For Your Heart? Eat More (Of This) For Lower Blood Pressure

(it’s fiber in the #1 spot, but there’s a list of most important things there, that’s worth checking out and comparing it to what you habitually eat)

You can also check out the DASH (Dietary Approaches to Stop Hypertension) edition of the Mediterranean diet, here:

Four Ways To Upgrade The Mediterranean Diet

As for saturated fat (and especially trans-fats), the basic answer is to keep them to minimal, but there is room for nuance with saturated fats at least:

Can Saturated Fats Be Healthy?

And lastly, do make sure to get enough omega 3 fatty-acids:

What Omega-3s Really Do For Us

And enjoy plant sterols and stanols! This would need a whole list of their own, so here you go:

Take These To Lower Cholesterol! (Statin Alternatives)

Take care!

Don’t Forget…

Did you arrive here from our newsletter? Don’t forget to return to the email to continue learning!

Learn to Age Gracefully

Join the 98k+ American women taking control of their health & aging with our 100% free (and fun!) daily emails:

-

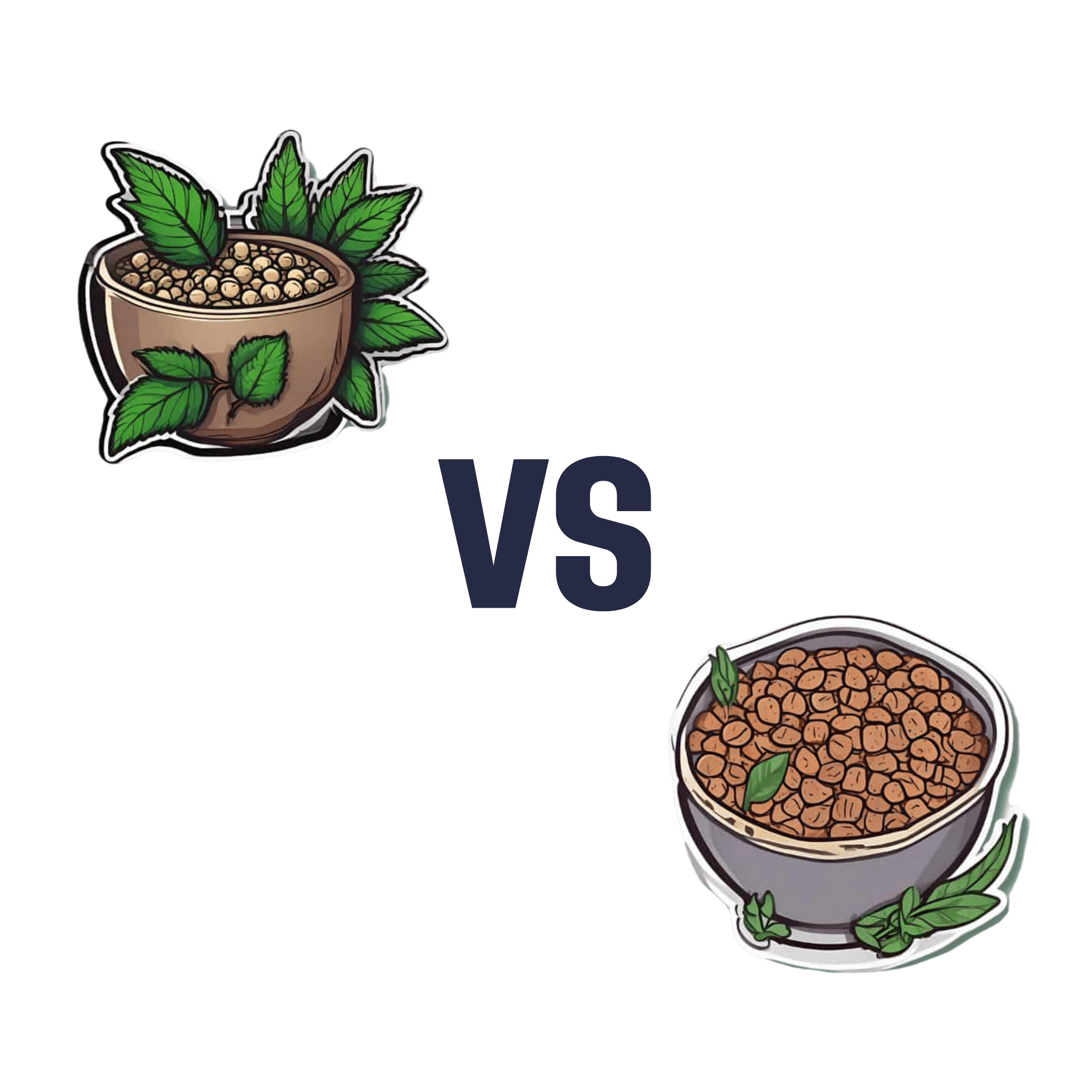

Hemp Seeds vs Flax Seeds – Which is Healthier?

10almonds is reader-supported. We may, at no cost to you, receive a portion of sales if you purchase a product through a link in this article.

Our Verdict

When comparing hemp seeds to flax seeds, we picked the flax.

Why?

Both are great, but quite differently so! In other words, they both have their advantages, but on balance, we prefer the flax’s advantages.

Part of this come from the way in which they are sold/consumed—hemp seeds must be hulled first, which means two things as a result:

- Flax seeds have much more fiber (about 8x more)

- Hemp seeds have more protein (about 2x more), proportionally, at least ← this is partly because they lost a bunch of weight by losing their fiber to the hulling, so the “per 100g” values of everything else go up, even though the amount per seed didn’t change

Since people’s diets are more commonly deficient in fiber than protein, and also since 8x is better than 2x, we consider this a win for flax.

Of course, many people enjoy hemp or flax specifically for the healthy fatty acids, so how do they stack up in that regard?

- Flax seeds have more omega-3s

- Hemp seeds have more omega-6s

This, for us, is a win for flax too, as the omega-3s are generally what we need more likely to be deficient in. Hemp enthusiasts, however, may argue that the internal balance of omega-3s to omega-6s is closer to an ideal ratio in hemp—but nutrition doesn’t exist in a vacuum, so we have to consider things “as part of a balanced diet” (because if one were trying to just live on hemp seeds, one would die), and most people’s diets are skewed far too far in favor or omega-6 compared to omega-3. So for most people, the higher levels of omega-3s are the more useful.

Want to learn more?

Take care!

Don’t Forget…

Did you arrive here from our newsletter? Don’t forget to return to the email to continue learning!

Learn to Age Gracefully

Join the 98k+ American women taking control of their health & aging with our 100% free (and fun!) daily emails:

-

What Is Earwax & Should You Get Rid Of It?

10almonds is reader-supported. We may, at no cost to you, receive a portion of sales if you purchase a product through a link in this article.

Earwax (cerumen) forms in the outer ear canal when dead skin cells mix with oily sweat (a specialty of the apocrine glands) and sebum, a fatty substance mostly associated with facial oiliness. But, does it have a purpose, or is it just a waste product?

Nature is (mostly) best in this case

Earwax plays an important role in ear health, acting as a natural lubricant that prevents dryness and itchiness, trapping debris and microbes, and forming a protective barrier for the ear canal. It even contains proteins that help fight bacterial infections.

As for removal: the body has a natural mechanism for removing excess earwax: as skin cells grow, they migrate outward, carrying earwax with them.

In contrast, manual removal of earwax can do more harm than good. Using swabs or other items often pushes wax deeper, risks damaging the ear canal, and disrupts its protective barrier, potentially leading to infection.

Ear candling, which claims to extract earwax, not only does not work (its main premise has been actively disproven and clinical evidence shows unequivocally that it doesn’t work by any mysterious method either; it just plain doesn’t work), but also can cause injuries and will tend to leave more harmful debris behind than was there originally.

For those prone to earwax buildup, over-the-counter eardrops can help soften wax for natural removal, and medical professionals have safe methods to clear blockages if necessary.

To maintain ear health, it’s best to clean only the outer ear with a damp cloth, limit the use of earplugs or earbuds, and generally leave earwax alone unless it causes discomfort or hearing issues.

For more on all of this, enjoy:

Click Here If The Embedded Video Doesn’t Load Automatically!

Want to learn more?

You might also like to read:

Ear Candling: Is It Safe & Does It Work? ← the answer is “no and no”, but the science may interest you

Take care!

Don’t Forget…

Did you arrive here from our newsletter? Don’t forget to return to the email to continue learning!

Learn to Age Gracefully

Join the 98k+ American women taking control of their health & aging with our 100% free (and fun!) daily emails: