Zuranolone: What to know about the pill for postpartum depression

10almonds is reader-supported. We may, at no cost to you, receive a portion of sales if you purchase a product through a link in this article.

In the year after giving birth, about one in eight people who give birth in the U.S. experience the debilitating symptoms of postpartum depression (PPD), including lack of energy and feeling sad, anxious, hopeless, and overwhelmed.

Postpartum depression is a serious, potentially life-threatening condition that can affect a person’s bond with their baby. Although it’s frequently confused with the so-called “baby blues,” it’s not the same.

The baby blues include similar, temporary symptoms that affect up to 80 percent of people who have recently given birth and usually go away within the first few weeks. PPD usually begins within the first month after giving birth and can last for months and interfere with a person’s daily life if left untreated. Thankfully, PPD is treatable and there is help available.

On August 4, the FDA approved zuranolone, branded as Zurzuvae, the first-ever oral medication to treat PPD. Until now, besides other common antidepressants, the only medication available to treat PPD specifically was the IV injection brexanolone, which is difficult to access and expensive and can only be administered in a hospital or health care setting.

Read on to find out more about zuranolone: what it is, how it works, how much it costs, and more.

What is zuranolone?

Zurzuvae is the brand name for zuranolone, an oral medication to treat postpartum depression. Developed by Sage Therapeutics in partnership with Biogen, it’s now available in the U.S. Zurzuvae is typically prescribed as two 25 mg capsules a day for 14 days. In clinical trials, the medication showed to be fast-acting, improving PPD symptoms in just three days.

How does zuranolone work?

Zuranolone is a neuroactive steroid, a type of medication that helps the neurotransmitter GABA’s receptors, which affect how the body reacts to anxiety, stress, and fear, function better.

“Zuranolone can be thought of as a synthetic version of [the neuroactive steroid] allopregnanolone,” says Dr. Katrina Furey, a reproductive psychiatrist, clinical instructor at Yale University, and co-host of the Analyze Scripts podcast. “Women with PPD have lower levels of allopregnenolone compared to women without PPD.”

How is it different from other antidepressants?

“What differentiates zuranolone from other previously available oral antidepressants is that it has a much more rapid response and a shorter course of treatment,” says Dr. Asima Ahmad, an OB-GYN, reproductive endocrinologist, and founder of Carrot Fertility.

“It can take effect as early as on day three of treatment, versus other oral antidepressants that can take up to six to 12 weeks to take full effect.”

What are Zurzuvae’s side effects?

According to the FDA, the most common side effects of Zurzuvae include dizziness, drowsiness, diarrhea, fatigue, the common cold, and urinary tract infection. Similar to other antidepressants, the medication may increase the risk of suicidal thoughts and actions in people 24 and younger. However, NPR noted that this type of labeling is required for all antidepressants, and researchers didn’t see any reports of suicidal thoughts in their trials.

“Drug trials also noted that the side effects for zuranolone were not as severe,” says Ahmad. “[There was] no sudden loss of consciousness as seen with brexanolone or weight gain and sexual dysfunction, which can be seen with other oral antidepressants.”

She adds: “Given the lower incidence of side effects and more rapid-acting onset, zuranolone could be a viable option for many,” including those looking for a treatment that offers faster symptom relief.

Can someone breastfeed while taking zuranolone?

It’s complicated. In clinical trials, participants were asked to stop breastfeeding (which, according to Furey, is common in early clinical trials).

A small study of people who were nursing while taking zuranolone found that 0.3 percent of the medication dose was passed on to breast milk, which, Furey says, is a pretty low amount of exposure for the baby. Ahmad says that “though some data suggests that the risk of harm to the baby may be low, there is still overall limited data.”

Overall, people should talk to their health care provider about the risks and benefits of breastfeeding while on the medication.

“A lot of factors will need to be weighed, such as overall health of the infant, age of the infant, etc., when making this decision,” Furey says.

How much does Zurzuvae cost?

Zurzuvae’s price before insurance coverage is $15,900 for the 14-day treatment. However, the Policy Center for Maternal Mental Health says insurance companies and Medicaid are expected to cover it because it’s the only drug of its kind.

Less than 1 percent of U.S. insurers have issued coverage guidelines so far, so it’s still unknown how much it will cost patients after insurance. Some insurers require patients to try another antidepressant first (like the more common SSRIs) before covering Zurzuvae. For uninsured and underinsured people, Sage Therapeutics said it will offer copay assistance.

The hefty price tag and potential issues with coverage may widen existing health disparities, says Ahmad. “We need to ensure that we are seeking out solutions to enable wide-scale access to all PPD treatments so that people have access to whatever treatment may work best for them.”

If you or anyone you know is considering suicide or self-harm or is anxious, depressed, upset, or needs to talk, call the Suicide & Crisis Lifeline at 988 or text the Crisis Text Line at 741-741. For international resources, here is a good place to begin.

For more information, talk to your health care provider.

This article first appeared on Public Good News and is republished here under a Creative Commons license.

Don’t Forget…

Did you arrive here from our newsletter? Don’t forget to return to the email to continue learning!

Recommended

Learn to Age Gracefully

Join the 98k+ American women taking control of their health & aging with our 100% free (and fun!) daily emails:

-

Learning to Love Midlife – by Chip Conley

10almonds is reader-supported. We may, at no cost to you, receive a portion of sales if you purchase a product through a link in this article.

While the book is titled about midlife, it could have said: midlife and beyond.

Some of the benefits discussed in this book really only kick in during one’s 50s, 60s, or 70s, usually. Which, for all but the most optimistic, is generally considered to be stretching beyond what is usually called “midlife”.

However! Chip Conley makes the argument for midlife being anywhere from one’s early 30s to mid-70s, depending on what (and how) we’re doing in life.

He talks about (as the subtitle promises) 12 reasons life gets better with age, and those reasons are grouped into 5 categories, thus:

- Physical life

- Emotional life

- Mental life

- Vocational life

- Spiritual life

It may surprise some readers that there are physical benefits that come with aging, but we do get two chapters in that category.

The writing style is very casual, yet with references to science throughout, and a bibliography for such.

Bottom line: if you’d like to make sure you’re making the most of your midlife and beyond, this a book that offers a lot of guidance on doing so!

Click here to check out Learning to Love Midlife, and age in style!

Share This Post

-

Blood, urine and other bodily fluids: how your leftover pathology samples can be used for medical research

10almonds is reader-supported. We may, at no cost to you, receive a portion of sales if you purchase a product through a link in this article.

A doctor’s visit often ends with you leaving with a pathology request form in hand. The request form soon has you filling a sample pot, having blood drawn, or perhaps even a tissue biopsy taken.

After that, your sample goes to a clinical pathology lab to be analysed, in whichever manner the doctor requested. All this is done with the goal of getting to the bottom of the health issue you’re experiencing.

But after all the tests are done, what happens with the leftover sample? In most cases, leftover samples go in the waste bin, destined for incineration. Sometimes though, they may be used again for other purposes, including research.

Kaboompics.com/Pexels Who can use my leftover samples?

The samples we’re talking about here cover the range of samples clinical labs receive in the normal course of their testing work. These include blood and its various components (including plasma and serum), urine, faeces, joint and spinal fluids, swabs (such as from the nose or a wound), and tissue samples from biopsies, among others.

Clinical pathology labs often use leftover samples to practise or check their testing methods and help ensure test accuracy. This type of use is a vital part of the quality assurance processes labs need to perform, and is not considered research.

Leftover samples can also be used by researchers from a range of agencies such as universities, research institutes or private companies.

They may use leftover samples for research activities such as trying out new ideas or conducting small-scale studies (more on this later). Companies that develop new or improved medical diagnostic tests can also use leftover samples to assess the efficacy of their test, generating data needed for regulatory approval.

What about informed consent?

If you’ve ever participated in a medical research project such as a clinical trial, you may be familiar with the concept of informed consent. In this process, you have the opportunity to learn about the study and what your participation involves, before you decide whether or not to participate.

So you may be surprised to learn using leftover samples for research purposes without your consent is permitted in most parts of Australia, and elsewhere. However, it’s only allowed under certain conditions.

In Australia, the National Health and Medical Research Council (NHMRC) offers guidance around the use of leftover pathology samples.

One of the conditions for using leftover samples without consent for research is that they were received and retained by an accredited pathology service. This helps ensure the samples were collected safely and properly, for a legitimate clinical reason, and that no additional burdens or risk of harm to the person who provided the sample will be created with their further use.

Another condition is anonymity: the leftover samples must be deidentified, and not easily able to be reidentified. This means they can only be used in research if the identity of the donor is not needed.

Leftover pathology samples are sometimes used in medical research. hedgehog94/Shutterstock The decision to allow a particular research project to use leftover pathology samples is made by an independent human research ethics committee which includes consumers and independent experts. The committee evaluates the project and weighs up the risks and potential benefits before permitting an exemption to the need for informed consent.

Similar frameworks exist in the United States, the United Kingdom, India and elsewhere.

What research might be done on my leftover samples?

You might wonder how useful leftover samples are, particularly when they’re not linked to a person and their medical history. But these samples can still be a valuable resource, particularly for early-stage “discovery” research.

Research using leftover samples has helped our understanding of antibiotic resistance in a bacterium that causes stomach ulcers, Helicobacter pylori. It has helped us understand how malaria parasites, Plasmodium falciparum, damage red blood cells.

Leftover samples are also helping researchers identify better, less invasive ways to detect chronic diseases such as pulmonary fibrosis. And they’re allowing scientists to assess the prevalence of a variant in haemoglobin that can interfere with widely used diagnostic blood tests.

All of this can be done without your permission. The kinds of tests researchers do on leftover samples will not harm the person they were taken from in any way. However, using what would otherwise be discarded allows researchers to test a new method or treatment and avoid burdening people with providing fresh samples specifically for the research.

When considering questions of ethics, it could be argued not using these samples to derive maximum benefit is in fact unethical, because their potential is wasted. Using leftover samples also minimises the cost of preliminary studies, which are often funded by taxpayers.

The use of leftover pathology samples in research has been subject to some debate. Andrey_Popov/Shutterstock Inconsistencies in policy

Despite NHMRC guidance, certain states and territories have their own legislation and guidelines which differ in important ways. For instance, in New South Wales, only pathology services may use leftover specimens for certain types of internal work. In all other cases consent must be obtained.

Ethical standards and their application in research are not static, and they evolve over time. As medical research continues to advance, so too will the frameworks that govern the use of leftover samples. Nonetheless, developing a nationally consistent approach on this issue would be ideal.

Striking a balance between ensuring ethical integrity and fostering scientific discovery is essential. With ongoing dialogue and oversight, leftover pathology samples will continue to play a crucial role in driving innovation and advances in health care, while respecting the privacy and rights of individuals.

Christine Carson, Senior Research Fellow, School of Medicine, The University of Western Australia and Nikolajs Zeps, Professor, School of Public Health and Preventive Medicine, Monash University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Share This Post

-

Is Unnoticed Environmental Mold Harming Your Health?

10almonds is reader-supported. We may, at no cost to you, receive a portion of sales if you purchase a product through a link in this article.

Environmental mold can be a lot more than just the famously toxic black mold that sometimes makes the headlines, and many kinds you might not notice, but it can colonizes your sinuses and gut just the same:

Breaking the mold

Around 25% of homes in North America are estimated to have mold, though the actual number is likely to be higher, affecting both older and new homes. For that matter, mold can grow in unexpected areas, like inside air conditioning units, even in dry regions.

If mold just sat where it is minding its own business, it might not be so bad, but instead they release their spores, which are de facto airborne mycotoxins, which can colonize places like the sinuses or gut, causing significant health issues.

Not everyone in the same household is affected the same way by mold due to genetic differences and varying pre-existing health conditions. But as a general rule of thumb, mold inflames the brain, nerves, gut, and skin, and can negatively impact the vagal nerve, which is linked to the gut-brain connection. Mycotoxins also damage mitochondria, leading to symptoms like fatigue, brain fog, and cognitive issues. To complicate matters further, mold illness can mimic other conditions like anxiety, chronic fatigue, fibromyalgia, IBS, and more, making it difficult to diagnose.

Testing is possible, though they all have limitations, e.g:

- Home testing: testing the home for mold spores and mycotoxins is crucial for effective treatment; professional mold remediation companies are a good idea (to do a thorough job of cleaning, without also breathing in half the mold while cleaning it).

- Mold allergy testing: mold allergy testing (IgE testing or skin tests) is often used, but it doesn’t diagnose mold-related illnesses linked to severe symptoms like fatigue or neurodegeneration.

- Serum antibody testing: tests for immune reactions (IgG) to mycotoxins may not always show positive results if the immune system is weakened by long-term exposure.

- Urine mycotoxin testing: urine tests can detect mycotoxins in the body, though are likely to be more expensive, being probably not covered by public health in Canada or insurance in the US.

- Organic acid testing: this urine test can indicate mold colonization in areas like the sinuses or gut. Again, cost/availability may vary, though.

For more information on all of this, enjoy:

Click Here If The Embedded Video Doesn’t Load Automatically!

Want to learn more?

You might also like to read:

Take care!

Share This Post

Related Posts

-

How Does One Test Acupuncture Against Placebo Anyway?

10almonds is reader-supported. We may, at no cost to you, receive a portion of sales if you purchase a product through a link in this article.

Pinpointing The Usefulness Of Acupuncture

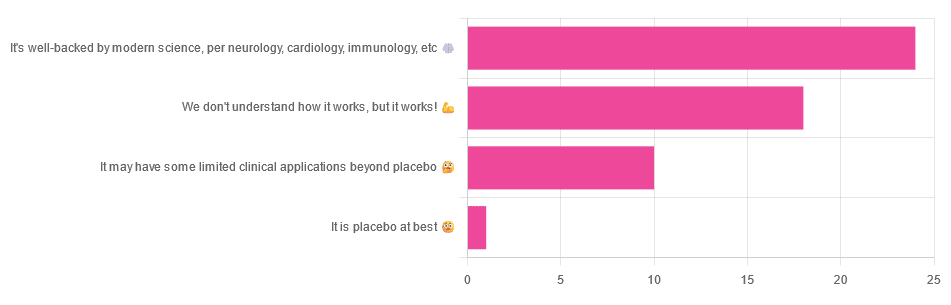

We asked you for your opinions on acupuncture, and got the above-depicted, below-described, set of answers:

- A little under half of all respondents voted for “It’s well-backed by modern science, per neurology, cardiology, immunology, etc”

- Slightly fewer respondents voted for “We don’t understand how it works, but it works!”

- A little under a fifth of respondents voted for “It may have some limited clinical applications beyond placebo”

- One (1) respondent voted for for “It’s placebo at best”

When we did a main feature about homeopathy, a couple of subscribers wrote to say that they were confused as to what homeopathy was, so this time, we’ll start with a quick definition first.

First, what is acupuncture? For the convenience of a quick definition so that we can move on to the science, let’s borrow from Wikipedia:

❝Acupuncture is a form of alternative medicine and a component of traditional Chinese medicine in which thin needles are inserted into the body.

Acupuncture is a pseudoscience; the theories and practices of TCM are not based on scientific knowledge, and it has been characterized as quackery.❞

Now, that’s not a promising start, but we will not be deterred! We will instead examine the science itself, rather than relying on tertiary sources like Wikipedia.

It’s worth noting before we move on, however, that there is vigorous debate behind the scenes of that article. The gist of the argument is:

- On one side: “Acupuncture is not pseudoscience/quackery! This has long been disproved and there are peer-reviewed research papers on the subject.”

- On the other: “Yes, but only in disreputable quack journals created specifically for that purpose”

The latter counterclaim is a) potentially a “no true Scotsman” rhetorical ploy b) potentially true regardless

Some counterclaims exhibit specific sinophobia, per “if the source is Chinese, don’t believe it”. That’s not helpful either.

Well, the waters sure are muddy. Where to begin? Let’s start with a relatively easy one:

It may have some clinical applications beyond placebo: True or False?

True! Admittedly, “may” is doing some of the heavy lifting here, but we’ll take what we can get to get us going.

One of the least controversial uses of acupuncture is to alleviate chronic pain. Dr. Vickers et al, in a study published under the auspices of JAMA (a very respectable journal, and based in the US, not China), found:

❝Acupuncture is effective for the treatment of chronic pain and is therefore a reasonable referral option. Significant differences between true and sham acupuncture indicate that acupuncture is more than a placebo.

However, these differences are relatively modest, suggesting that factors in addition to the specific effects of needling are important contributors to the therapeutic effects of acupuncture❞

Source: Acupuncture for Chronic Pain: Individual Patient Data Meta-analysis

If you’re feeling sharp today, you may be wondering how the differences are described as “significant” and “relatively modest” in the same text. That’s because these words have different meanings in academic literature:

- Significant = p<0.05, where p is the probability of the achieved results occurring randomly

- Modest = the differences between the test group and the control group were small

In other words, “significant modest differences” means “the sample sizes were large, and the test group reliably got slightly better results than placebo”

We don’t understand how it works, but it works: True or False

Broadly False. When it works, we generally have an idea how.

Placebo is, of course, the main explanation. And even in examples such as the above, how is placebo acupuncture given?

By inserting acupuncture needles off-target rather than in accord with established meridians and points (the lines and dots that, per Traditional Chinese Medicine, indicate the flow of qi, our body’s vital energy, and welling-points of such).

So, if a patient feels that needles are being inserted randomly, they may no longer have the same confidence that they aren’t in the control group receiving placebo, which could explain the “modest” difference, without there being anything “to” acupuncture beyond placebo. After all, placebo works less well if you believe you are only receiving placebo!

Indeed, a (Korean, for the record) group of researchers wrote about this—and how this confounding factor cuts both ways:

❝Given the current research evidence that sham acupuncture can exert not only the originally expected non-specific effects but also sham acupuncture-specific effects, it would be misleading to simply regard sham acupuncture as the same as placebo.

Therefore, researchers should be cautious when using the term sham acupuncture in clinical investigations.❞

Source: Sham Acupuncture Is Not Just a Placebo

It’s well-backed by modern science, per neurology, cardiology, immunology, etc: True or False?

False, for the most part.

While yes, the meridians and points of acupuncture charts broadly correspond to nerves and vasculature, there is no evidence that inserting needles into those points does anything for one’s qi, itself a concept that has not made it into Western science—as a unified concept, anyway…

Note that our bodies are indeed full of energy. Electrical energy in our nerves, chemical energy in every living cell, kinetic energy in all our moving parts. Even, to stretch the point a bit, gravitational potential energy based on our mass.

All of these things could broadly be described as qi, if we so wish. Indeed, the ki in the Japanese martial art of aikido is the latter kinds; kinetic energy and gravitational potential energy based on our mass. Same goes, therefore for the ki in kiatsu, a kind of Japanese massage, while the ki in reiki, a Japanese spiritual healing practice, is rather more mystical.

The qi in Chinese qigong is mostly about oxygen, thus indirectly chemical energy, and the electrical energy of the nerves that are receiving oxygenated blood at higher or lower levels.

On the other hand, the efficacy of the use of acupuncture for various kinds of pain is well-enough evidenced. Indeed, even the UK’s famously thrifty NHS (that certainly would not spend money on something it did not find to work) offers it as a complementary therapy for some kinds of pain:

❝Western medical acupuncture (dry needling) is the use of acupuncture following a medical diagnosis. It involves stimulating sensory nerves under the skin and in the muscles.

This results in the body producing natural substances, such as pain-relieving endorphins. It’s likely that these naturally released substances are responsible for the beneficial effects experienced with acupuncture.❞

Source: NHS | Acupuncture

Meanwhile, the NIH’s National Cancer Institute recommends it… But not as a cancer treatment.

Rather, they recommend it as a complementary therapy for pain management, and also against nausea, for which there is also evidence that it can help.

Frustratingly, while they mention that there is lots of evidence for this, they don’t actually link the studies they’re citing, or give enough information to find them. Instead, they say things like “seven randomized clinical trials found that…” and provide links that look reassuring until one finds, upon clicking on them, that it’s just a link to the definition of “randomized clinical trial”:

Source: NIH | Nactional Cancer Institute | Acupuncture (PDQ®)–Patient Version

However, doing our own searches finds many studies (mostly in specialized, potentially biased, journals such as the Journal of Acupuncture and Meridian Studies) finding significant modest outperformance of [what passes for] placebo.

Sometimes, the existence of papers with promising titles, and statements of how acupuncture might work for things other than relief of pain and nausea, hides the fact that the papers themselves do not, in fact, contain any evidence to support the hypothesis. Here’s an example:

❝The underlying mechanisms behind the benefits of acupuncture may be linked with the regulation of the hypothalamic-pituitary-gonadal (adrenal) axis and activation of the Wnt/β-catenin and OPG/RANKL/RANK signaling pathways.

In summary, strong evidence may still come from prospective and well-designed clinical trials to shed light on the potential role of acupuncture in preserving bone loss❞

Source: Acupuncture for Osteoporosis: a Review of Its Clinical and Preclinical Studies

So, here they offered a very sciencey hypothesis, and to support that hypothesis, “strong evidence may still come”.

“We must keep faith” is not usually considered evidence worthy of inclusion in a paper!

PS: the above link is just to the abstract, because the “Full Text” link offered in that abstract leads to a completely unrelated article about HIV/AIDS-related cryptococcosis, in a completely different journal, nothing to do with acupuncture or osteoporosis).

Again, this is not the kind of professionalism we expect from peer-reviewed academic journals.

Bottom line:

Acupuncture reliably performs slightly better than sham acupuncture for the management of pain, and may also help against nausea.

Beyond placebo and the stimulation of endorphin release, there is no consistently reliable evidence that is has any other discernible medical effect by any mechanism known to Western science—though there are plenty of hypotheses.

That said, absence of evidence is not evidence of absence, and the logistical difficulty of testing acupuncture against placebo makes for slow research. Maybe one day we’ll know more.

For now:

- If you find it helps you: great! Enjoy

- If you think it might help you: try it! By a licensed professional with a good reputation, please.

- If you are not inclined to having needles put in you unnecessarily: skip it! Extant science suggests that at worst, you’ll be missing out on slight relief of pain/nausea.

Take care!

Don’t Forget…

Did you arrive here from our newsletter? Don’t forget to return to the email to continue learning!

Learn to Age Gracefully

Join the 98k+ American women taking control of their health & aging with our 100% free (and fun!) daily emails:

-

You can train your nose – and 4 other surprising facts about your sense of smell

10almonds is reader-supported. We may, at no cost to you, receive a portion of sales if you purchase a product through a link in this article.

Would you give up your sense of smell to keep your hair? What about your phone?

A 2022 US study compared smell to other senses (sight and hearing) and personally prized commodities (including money, a pet or hair) to see what people valued more.

The researchers found smell was viewed as much less important than sight and hearing, and valued less than many commodities. For example, half the women surveyed said they’d choose to keep their hair over sense of smell.

Smell often goes under the radar as one of the least valued senses. But it is one of the first sensory systems vertebrates developed and is linked to your mental health, memory and more.

Here are five fascinating facts about your olfactory system.

DimaBerlin/Shutterstock 1. Smell is linked to memory and emotion

Why can the waft of fresh baking trigger joyful childhood memories? And why might a certain perfume jolt you back to a painful breakup?

Smell is directly linked to both your memory and emotions. This connection was first established by American psychologist Donald Laird in 1935 (although French novelist Marcel Proust had already made it famous in his reverie about the scent of madeleines baking.)

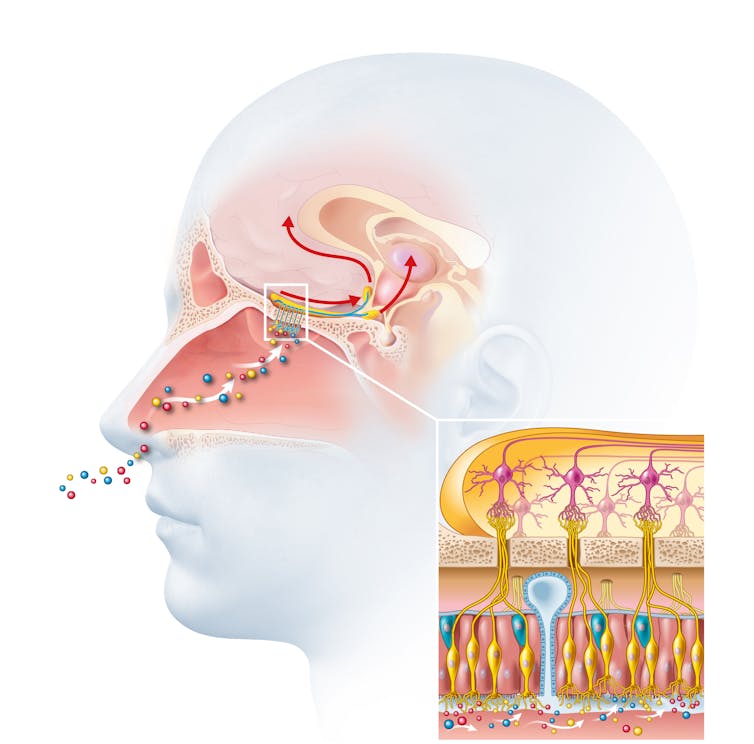

Odours are first captured by special olfactory nerve cells inside your nose. These cells extend upwards from the roof of your nose towards the smell-processing centre of your brain, called the olfactory bulb.

Smells are first detected by nerve cells in the nose. Axel_Kock/Shutterstock From the olfactory bulb they form direct connection with the brain’s limbic system. This includes the amygdala, where emotions are generated, and the hippocampus, where memories are created.

Other senses – such as sight and hearing – aren’t directly connected to the lymbic system.

One 2004 study used functional magnetic resonance imaging to demonstrate odours trigger a much stronger emotional and memory response in the brain than a visual cue.

2. Your sense of smell constantly regenerates

You can lose your ability to smell due to injury or infection – for example during and after a COVID infection. This is known as olfactory dysfunction. In most cases it’s temporary, returning to normal within a few weeks.

This is because every few months your olfactory nerve cells die and are replaced by new cells.

We’re not entirely sure how this occurs, but it likely involves your nose’s stem cells, the olfactory bulb and other cells in the olfactory nerves.

Other areas of your nervous system – including your brain and spinal cord – cannot regenerate and repair after an injury.

Constant regeneration may be a protective mechanism, as the olfactory nerves are vulnerable to damage caused by the external environment, including toxins (such as cigarette smoke), chemicals and pathogens (such as the flu virus).

But following a COVID infection some people might continue to experience a loss of smell. Studies suggest the virus and a long-term immune response damages the cells that allow the olfactory system to regenerate.

3. Smell is linked to mental health

Around 5% of the global population suffer from anosmia – total loss of smell. An estimated 15-20% suffer partial loss, known as hyposmia.

Given smell loss is often a primary and long-term symptom of COVID, these numbers are likely to be higher since the pandemic.

Yet in Australia, the prevalence of olfactory dysfunction remains surprisingly understudied.

Losing your sense of smell is shown to impact your personal and social relationships. For example, it can mean you miss out on shared eating experiences, or cause changes in sexual desire and behaviour.

In older people, declining ability to smell is associated with a higher risk of depression and even death, although we still don’t know why.

Losing your sense of smell can have a major impact on mental health. Halfpoint/Shutterstock 4. Loss of smell can help identify neurodegenerative diseases

Partial or full loss of smell is often an early indicator for a range of neurodegenerative diseases, including Alzheimer’s and Parkinson’s diseases.

Patients frequently report losing their sense of smell years before any symptoms show in body or brain function. However many people are not aware they are losing their sense of smell.

There are ways you can determine if you have smell loss and to what extent. You may be able to visit a formal smell testing centre or do a self-test at home, which assesses your ability to identify household items like coffee, wine or soap.

5. You can train your nose back into smelling

“Smell training” is emerging as a promising experimental treatment option for olfactory dysfunction. For people experiencing smell loss after COVID, it’s been show to improve the ability to detect and differentiate odours.

Smell training (or “olfactory training”) was first tested in 2009 in a German psychology study. It involves sniffing robust odours — such as floral, citrus, aromatic or fruity scents — at least twice a day for 10—20 seconds at a time, usually over a 3—6 month period.

Participants are asked to focus on the memory of the smell while sniffing and recall information about the odour and its intensity. This is believed to help reorganise the nerve connections in the brain, although the exact mechanism behind it is unclear.

Some studies recommend using a single set of scents, while others recommend switching to a new set of odours after a certain amount of time. However both methods show significant improvement in smelling.

This training has also been shown to alleviate depressive symptoms and improve cognitive decline both in older adults and those suffering from dementia.

Just like physiotherapy after a physical injury, olfactory training is thought to act like rehabilitation for your sense of smell. It retrains the nerves in your nose and the connections it forms within the brain, allowing you to correctly detect, process and interpret odours.

Lynn Nazareth, Research Scientist in Olfactory Biology, CSIRO

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Don’t Forget…

Did you arrive here from our newsletter? Don’t forget to return to the email to continue learning!

Learn to Age Gracefully

Join the 98k+ American women taking control of their health & aging with our 100% free (and fun!) daily emails:

-

Peas vs Green Beans – Which is Healthier?

10almonds is reader-supported. We may, at no cost to you, receive a portion of sales if you purchase a product through a link in this article.

Our Verdict

When comparing peas to green beans, we picked the peas.

Why?

Looking at macros first, peas have nearly 6x the protein, nearly 2x the fiber, and nearly 2x the carbs, making them the “more food per food” choice.

In terms of vitamins, peas have more of vitamins A, B1, B2, B3, B5, B6, B7, B9, C, and choline, while green beans have more of vitamins E and K. An easy win for peas.

In the category of minerals, peas have more copper, iron, magnesium, manganese, phosphorus, potassium, selenium, and zinc, while green beans have more calcium. Another overwhelming win for peas.

In short, enjoy both (diversity is good), but there’s a clear winner here and it’s peas.

Want to learn more?

You might like to read:

Peas vs Broad Beans – Which is Healthier?

Take care!

Don’t Forget…

Did you arrive here from our newsletter? Don’t forget to return to the email to continue learning!

Learn to Age Gracefully

Join the 98k+ American women taking control of their health & aging with our 100% free (and fun!) daily emails: