We looked at genetic clues to depression in more than 14,000 people. What we found may surprise you

10almonds is reader-supported. We may, at no cost to you, receive a portion of sales if you purchase a product through a link in this article.

The core experiences of depression – changes in energy, activity, thinking and mood – have been described for more than 10,000 years. The word “depression” has been used for about 350 years.

Given this long history, it may surprise you that experts don’t agree about what depression is, how to define it or what causes it.

But many experts do agree that depression is not one thing. It’s a large family of illnesses with different causes and mechanisms. This makes choosing the best treatment for each person challenging.

Reactive vs endogenous depression

One strategy is to search for sub-types of depression and see whether they might do better with different kinds of treatments. One example is contrasting “reactive” depression with “endogenous” depression.

Reactive depression (also thought of as social or psychological depression) is presented as being triggered by exposure to stressful life events. These might be being assaulted or losing a loved one – an understandable reaction to an outside trigger.

Endogenous depression (also thought of as biological or genetic depression) is proposed to be caused by something inside, such as genes or brain chemistry.

Many people working clinically in mental health accept this sub-typing. You might have read about this online.

But we think this approach is way too simple.

While stressful life events and genes may, individually, contribute to causing depression, they also interact to increase the risk of someone developing depression. And evidence shows that there is a genetic component to being exposed to stressors. Some genes affect things such as personality. Some affect how we interact with our environments.

What we did and what we found

Our team set out to look at the role of genes and stressors to see if classifying depression as reactive or endogenous was valid.

In the Australian Genetics of Depression Study, people with depression answered surveys about exposure to stressful life events. We analysed DNA from their saliva samples to calculate their genetic risk for mental disorders.

Our question was simple. Does genetic risk for depression, bipolar disorder, schizophrenia, ADHD, anxiety and neuroticism (a personality trait) influence people’s reported exposure to stressful life events?

You may be wondering why we bothered calculating the genetic risk for mental disorders in people who already have depression. Every person has genetic variants linked to mental disorders. Some people have more, some less. Even people who already have depression might have a low genetic risk for it. These people may have developed their particular depression from some other constellation of causes.

We looked at the genetic risk of conditions other than depression for a couple of reasons. First, genetic variants linked to depression overlap with those linked to other mental disorders. Second, two people with depression may have completely different genetic variants. So we wanted to cast a wide net to look at a wider spectrum of genetic variants linked to mental disorders.

If reactive and endogenous depression sub-types are valid, we’d expect people with a lower genetic component to their depression (the reactive group) would report more stressful life events. And we’d expect those with a higher genetic component (the endogenous group) would report fewer stressful life events.

But after studying more than 14,000 people with depression we found the opposite.

We found people at higher genetic risk for depression, anxiety, ADHD or schizophrenia say they’ve been exposed to more stressors.

Assault with a weapon, sexual assault, accidents, legal and financial troubles, and childhood abuse and neglect, were all more common in people with a higher genetic risk of depression, anxiety, ADHD or schizophrenia.

These associations were not strongly influenced by people’s age, sex or relationships with family. We didn’t look at other factors that may influence these associations, such as socioeconomic status. We also relied on people’s memory of past events, which may not be accurate.

How do genes play a role?

Genetic risk for mental disorders changes people’s sensitivity to the environment.

Imagine two people, one with a high genetic risk for depression, one with a low risk. They both lose their jobs. The genetically vulnerable person experiences the job loss as a threat to their self-worth and social status. There is a sense of shame and despair. They can’t bring themselves to look for another job for fear of losing it too. For the other, the job loss feels less about them and more about the company. These two people internalise the event differently and remember it differently.

Genetic risk for mental disorders also might make it more likely people find themselves in environments where bad things happen. For example, a higher genetic risk for depression might affect self-worth, making people more likely to get into dysfunctional relationships which then go badly.

What does our study mean for depression?

First, it confirms genes and environments are not independent. Genes influence the environments we end up in, and what then happens. Genes also influence how we react to those events.

Second, our study doesn’t support a distinction between reactive and endogenous depression. Genes and environments have a complex interplay. Most cases of depression are a mix of genetics, biology and stressors.

Third, people with depression who appear to have a stronger genetic component to their depression report their lives are punctuated by more serious stressors.

So clinically, people with higher genetic vulnerability might benefit from learning specific techniques to manage their stress. This might help some people reduce their chance of developing depression in the first place. It might also help some people with depression reduce their ongoing exposure to stressors.

If this article has raised issues for you, or if you’re concerned about someone you know, call Lifeline on 13 11 14.

Jacob Crouse, Research Fellow in Youth Mental Health, Brain and Mind Centre, University of Sydney and Ian Hickie, Co-Director, Health and Policy, Brain and Mind Centre, University of Sydney

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Don’t Forget…

Did you arrive here from our newsletter? Don’t forget to return to the email to continue learning!

Recommended

Learn to Age Gracefully

Join the 98k+ American women taking control of their health & aging with our 100% free (and fun!) daily emails:

-

How the stress of playing chess can be fatal

10almonds is reader-supported. We may, at no cost to you, receive a portion of sales if you purchase a product through a link in this article.

The death of a chess player in the middle of a match at the world’s most prestigious competition may have shocked those who view the game as a relaxing pastime. Kurt Meier, 67, collapsed during his final match in the tournament and died in hospital later that day. But chess, like any other game or sport, can lead to an immense amount of stress, which can be bad for a competitor’s physical health too.

We tend to associate playing sport or games with good health and well-being. And there are a countless number of studies showing playing games has an association with feeling happier. While this argument is true for recreational players, the story can be different for the elite, where success and failure are won and lost by the finest margins and where winning can mean funding and a future, and losing can mean poverty and unemployment. If this is the case, can being successful at a sport or game actually be bad for you?

Competitive anxiety

Elite competition can be stressful because the outcome is so important to the competitors. We can measure stress using a whole range of physiological indicators such as heart rate and temperature, and responses such as changes in the intensity of our emotions.

Emotions provide a warning of threat. So if you feel that achieving your goal is going to be difficult, then expect to feel intense emotions. The leading candidate that signals we are experiencing stress is anxiety, characterised by thoughts of worry, fears of dread about performance, along with accompanying physiological responses such as increased heart rate and sweaty palms. If these symptoms are experienced regularly or chronically, then this is clearly detrimental to health.

This stress response is probably not restricted to elite athletes. Intense emotions are linked to trying to achieve important goals and while it isn’t the only situation where it occurs, it is just very noticeable in sport.

The causes of stress

It makes more sense to focus on what the causes of stress are rather than where we experience it. The principle is that the more important the goal is to achieve, then the greater the propensity for the situation to intensify emotions.

Emotions intensify also by the degree of uncertainty and competing, at whatever level of a sport, is uncertain when the opposition is trying its hardest to win the contest and also has a motivation to succeed. The key point is that almost all athletes at any level can suffer bouts of stress, partly due to high levels of motivation.

A stress response is also linked to how performance is judged and reported. Potentially stressful tasks tend to be ones where performance is public and feedback is immediate. In chess – as with most sporting contests – we see who the winner is and can start celebrating success or commiserating failure as soon as the game is over.

There are many tasks which have similar features. Giving a speech in public, taking an academic examination, or taking your driving test are all examples of tasks that can illicit stress. Stress is not restricted to formal tasks but can also include social tasks. Asking a potential partner for a date, hand in marriage, and meeting the in-laws for the first time can be equally stressful.

Winning a contest or going on a date relate to higher-order goals about how we see ourselves. If we define ourselves as “being a good player” or “being attractive or likeable” then contrasting information is likely to associate with unpleasant emotions. You will feel devastated if you are turned down when asking someone out on a date, for instance, and if this was repeated, it could lead to reduced self-esteem and depression.

The key message here is to recognise what your goals are and think about how important they are. If you want to achieve them with a passion and if the act of achieving them leads to intense and sometimes unwanted emotions, then it’s worth thinking about doing some work to manage these emotions.

Andrew Lane, Professor in Sport and Learning, University of Wolverhampton

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Share This Post

-

Anti-Inflammatory Brownies

10almonds is reader-supported. We may, at no cost to you, receive a portion of sales if you purchase a product through a link in this article.

Brownies are usually full of sugar, butter, and flour. These ones aren’t! Instead, they’re full of fiber (good against inflammation), healthy fats, and anti-inflammatory polyphenols:

You will need

- 1 can chickpeas (keep half the chickpea water, also called aquafaba, as we’ll be using it)

- 4 oz of your favorite nut butter (substitute with tahini if you’re allergic to nuts)

- 3 oz rolled oats

- 2 oz dark chocolate chips (or if you want the best quality: dark chocolate, chopped into very small pieces)

- 3 tbsp of your preferred plant milk (this is an anti-inflammatory recipe and unfermented dairy is inflammatory)

- 2 tbsp cocoa powder (pure cacao is best)

- 1 tbsp glycine (if unavailable, use 2 tbsp maple syrup, and skip the aquafaba)

- 2 tsp vanilla extract

- ½ tsp baking powder

- ¼ tsp low-sodium salt

Method

(we suggest you read everything at least once before doing anything)

1) Preheat the oven to 350℉ / 180℃, and line a 7″ cake tin with baking paper.

2) Blend the oats in a food processor, until you have oat flour.

3) Add all the remaining ingredients except the dark chocolate chips, and process until the mixture resembles cookie dough.

3) Transfer to a bowl, and fold in the dark chocolate chips, distributing evenly.

4) Add the mixture to the cake tin, and smooth the surface down so that it’s flat and even. Bake for about 25 minutes, and let them cool in the tin for at least 10 minutes, but longer is better, as they will firm up while they cool. Cut into cubes when ready to serve:

Enjoy!

Want to learn more?

For those interested in some of the science of what we have going on today:

- Level-Up Your Fiber Intake! (Without Difficulty Or Discomfort)

- Cacao vs Carob – Which is Healthier?

- Keep Inflammation At Bay

- The Sweet Truth About Glycine

- The Best Kind Of Fiber For Overall Health?

Take care!

Share This Post

-

Microplastics are in our brains. How worried should I be?

10almonds is reader-supported. We may, at no cost to you, receive a portion of sales if you purchase a product through a link in this article.

Plastic is in our clothes, cars, mobile phones, water bottles and food containers. But recent research adds to growing concerns about the impact of tiny plastic fragments on our health.

A study from the United States has, for the first time, found microplastics in human brains. The study, which has yet to be independently verified by other scientists, has been described in the media as scary, shocking and alarming.

But what exactly are microplastics? What do they mean for our health? Should we be concerned?

Daniel Megias/Shutterstock What are microplastics? Can you see them?

We often consider plastic items to be indestructible. But plastic breaks down into smaller particles. Definitions vary but generally microplastics are smaller than five millimetres.

This makes some too small to be seen with the naked eye. So, many of the images the media uses to illustrate articles about microplastics are misleading, as some show much larger, clearly visible pieces.

Microplastics have been reported in many sources of drinking water and everyday food items. This means we are constantly exposed to them in our diet.

Such widespread, chronic (long-term) exposure makes this a serious concern for human health. While research investigating the potential risk microplastics pose to our health is limited, it is growing.

How about this latest study?

The study looked at concentrations of microplastics in 51 samples from men and women set aside from routine autopsies in Albuquerque, New Mexico. Samples were from the liver, kidney and brain.

These tiny particles are difficult to study due to their size, even with a high-powered microscope. So rather than trying to see them, researchers are beginning to use complex instruments that identify the chemical composition of microplastics in a sample. This is the technique used in this study.

The researchers were surprised to find up to 30 times more microplastics in brain samples than in the liver and kidney.

They hypothesised this could be due to high blood flow to the brain (carrying plastic particles with it). Alternatively, the liver and kidneys might be better suited to dealing with external toxins and particles. We also know the brain does not undergo the same amount of cellular renewal as other organs in the body, which could make the plastics linger here.

The researchers also found the amount of plastics in brain samples increased by about 50% between 2016 and 2024. This may reflect the rise in environmental plastic pollution and increased human exposure.

The microplastics found in this study were mostly composed of polyethylene. This is the most commonly produced plastic in the world and is used for many everyday products, such as bottle caps and plastic bags.

This is the first time microplastics have been found in human brains, which is important. However, this study is a “pre-print”, so other independent microplastics researchers haven’t yet reviewed or validated the study.

The most common plastic found was polyethylene, which is used to make plastic bags and bottle caps. Maciej Bledowski/Shutterstock How do microplastics end up in the brain?

Microplastics typically enter the body through contaminated food and water. This can disrupt the gut microbiome (the community of microbes in your gut) and cause inflammation. This leads to effects in the whole body via the immune system and the complex, two-way communication system between the gut and the brain. This so-called gut-brain axis is implicated in many aspects of health and disease.

We can also breathe in airborne microplastics. Once these particles are in the gut or lungs, they can move into the bloodstream and then travel around the body into various organs.

Studies have found microplastics in human faeces, joints, livers, reproductive organs, blood, vessels and hearts.

Microplastics also migrate to the brains of wild fish. In mouse studies, ingested microplastics are absorbed from the gut into the blood and can enter the brain, becoming lodged in other organs along the way.

To get into brain tissue, microplastics must cross the blood-brain-barrier, an intricate layer of cells that is supposed to keep things in the blood from entering the brain.

Although concerning, this is not surprising, as microplastics must cross similar cell barriers to enter the urine, testes and placenta, where they have already been found in humans.

Is this a health concern?

We don’t yet know the effects of microplastics in the human brain. Some laboratory experiments suggest microplastics increase brain inflammation and cell damage, alter gene expression and change brain structure.

Aside from the effects of the microplastic particles themselves, microplastics might also pose risks if they carry environmental toxins or bacteria into and around the body.

Various plastic chemicals could also leach out of the microplastics into the body. These include the famous hormone-disrupting chemicals known as BPAs.

But microplastics and their effects are difficult to study. In addition to their small size, there are so many different types of plastics in the environment. More than 13,000 different chemicals have been identified in plastic products, with more being developed every year.

Microplastics are also weathered by the environment and digestive processes, and this is hard to reproduce in the lab.

A goal of our research is to understand how these factors change the way microplastics behave in the body. We plan to investigate if improving the integrity of the gut barrier through diet or probiotics can prevent the uptake of microplastics from the gut into the bloodstream. This may effectively stop the particles from circulating around the body and lodging into organs.

How do I minimise my exposure?

Microplastics are widespread in the environment, and it’s difficult to avoid exposure. We are just beginning to understand how microplastics can affect our health.

Until we have more scientific evidence, the best thing we can do is reduce our exposure to plastics where we can and produce less plastic waste, so less ends up in the environment.

An easy place to start is to avoid foods and drinks packaged in single-use plastic or reheated in plastic containers. We can also minimise exposure to synthetic fibres in our home and clothing.

Sarah Hellewell, Senior Research Fellow, The Perron Institute for Neurological and Translational Science, and Research Fellow, Faculty of Health Sciences, Curtin University; Anastazja Gorecki, Teaching & Research Scholar, School of Health Sciences, University of Notre Dame Australia, and Charlotte Sofield, PhD Candidate, studying microplastics and gut/brain health, University of Notre Dame Australia

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Share This Post

Related Posts

-

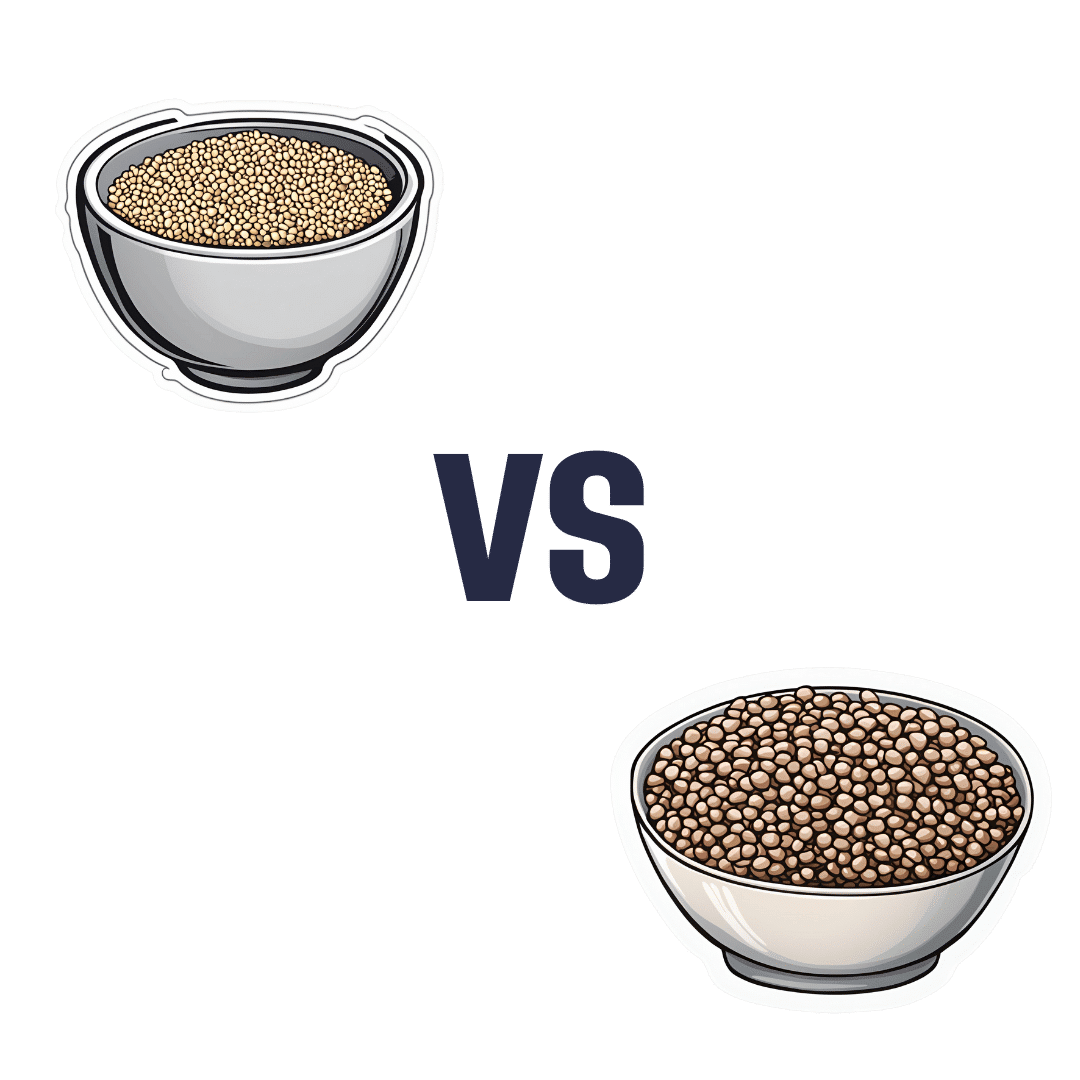

Millet vs Buckwheat – Which is Healthier?

10almonds is reader-supported. We may, at no cost to you, receive a portion of sales if you purchase a product through a link in this article.

Our Verdict

When comparing millet to buckwheat, we picked the buckwheat.

Why?

Both of these naturally gluten-free grains* have their merits, but we say buckwheat comes out on top for most people (we’ll discuss the exception later).

*actually buckwheat is a flowering pseudocereal, but in culinary terms, we’ll call it a grain, much like we call tomato a vegetable.

Considering the macros first of all, millet has slightly more carbs while buckwheat has more than 2x the fiber. An easy win for buckwheat (they’re about equal on protein, by the way).

In the category of vitamins, millet has more of vitamins B1, B2, B3, B6, and B9, while buckwheat has more of vitamins B5, E, K, and choline. Superficially that’s a 5:4 win for millet, though buckwheat’s margins of difference are notably greater, so the overall vitamin coverage could arguably be considered a tie.

When it comes to minerals, millet has more phosphorus and zinc, while buckwheat has more calcium, copper, iron, magnesium, manganese, potassium, and selenium. For most of them, buckwheat’s margins of difference are again greater. An easy win for buckwheat, in any case.

This all adds up to a clear win for buckwheat, but as promised, there is an exception: if you have issues with your kidneys that mean you are avoiding oxalates, then millet becomes the healthier choice, as buckwheat is rather high in oxalates while millet is low in same.

For everyone else: enjoy both! Diversity is good. But if you’re going to pick one, buckwheat’s the winner.

Want to learn more?

You might like to read:

Grains: Bread Of Life, Or Cereal Killer?

Take care!

Don’t Forget…

Did you arrive here from our newsletter? Don’t forget to return to the email to continue learning!

Learn to Age Gracefully

Join the 98k+ American women taking control of their health & aging with our 100% free (and fun!) daily emails:

-

Rethinking Diabetes – by Gary Taubes

10almonds is reader-supported. We may, at no cost to you, receive a portion of sales if you purchase a product through a link in this article.

We’ve previously reviewed this author’s “The Case Against Sugar” and “Why We Get Fat And What To Do About It“. There’s an obvious theme, and this book caps it off nicely:

By looking at the history of diabetes treatment (types 1 and 2) in the past hundred years, and analysing the patterns over time, we can see how:

- diabetics have been misled a lot over time by healthcare providers

- we can learn from those mistakes going forwards

Happily, he does this without crystal-balling the future or expecting diet to fix, for example, a pancreas that can’t produce insulin. But what he does do is focus on the “can” items rather than the “can’t” items.

In the category of criticism, one of the strategies he argues for is basically the keto diet, which is indeed just fine for diabetes but often not great for the heart in the long-term (it depends on various factors, including genes). However, even if you choose not to implement that, there is plenty more to try out in this book.

Bottom line: whether you have diabetes, love someone who does, or just plain like to be on top of your glycemic health, this book is full of important insights and opportunities to improve things progressively along the way.

Click here to check out Rethinking Diabetes, and rethink diabetes!

Don’t Forget…

Did you arrive here from our newsletter? Don’t forget to return to the email to continue learning!

Learn to Age Gracefully

Join the 98k+ American women taking control of their health & aging with our 100% free (and fun!) daily emails:

-

Daily, Weekly, Monthly: Habits Against Aging

10almonds is reader-supported. We may, at no cost to you, receive a portion of sales if you purchase a product through a link in this article.

Dr. Anil Rajani has advice on restoring/retaining youthfulness. Two out of three of the sections are on skincare specifically, which may seem a vanity, but it’s also worth remembering that our skin is a very large and significant organ, and makes a big difference for the rest of our physical health, as well as our mental health. So, it’s worthwhile to look after it:

The recommendations

Daily: meditation practice

Meditation reduces stress, which reduction in turn protects telomere length, slowing the overall aging process in every living cell of the body.

Weekly: skincare basics

Dr. Rajani recommends a combination of retinol and glycolic acid. The former to accelerate cell turnover, stimulate collagen production, and reduce wrinkles; the latter, to exfoliate dead cells, allowing the retinol to do its job more effectively.

We at 10almonds would like to add: wearing sunscreen with SPF50 is a very good thing to do on any day that your phone’s weather app says the UV index is “moderate” or higher.

Monthly: skincare extras

Here are the real luxuries; spa visits, microneedling (stimulates collagen production), and non-ablative laser therapy. He recommends creating a home spa if possible for monthly skincare treatments, investing in high-quality devices for long-term benefits.

For more on all of these things, enjoy:

Click Here If The Embedded Video Doesn’t Load Automatically!

Want to learn more?

You might also like to read:

- Age & Aging: What Can (And Can’t) We Do About It?

- No-Frills, Evidence-Based Mindfulness

- The Evidence-Based Skincare That Beats Product-Specific Hype

Take care!

Don’t Forget…

Did you arrive here from our newsletter? Don’t forget to return to the email to continue learning!

Learn to Age Gracefully

Join the 98k+ American women taking control of their health & aging with our 100% free (and fun!) daily emails: