Viruses aren’t always harmful. 6 ways they’re used in health care and pest control

10almonds is reader-supported. We may, at no cost to you, receive a portion of sales if you purchase a product through a link in this article.

We tend to just think of viruses in terms of their damaging impacts on human health and lives. The 1918 flu pandemic killed around 50 million people. Smallpox claimed 30% of those who caught it, and survivors were often scarred and blinded. More recently, we’re all too familiar with the health and economic impacts of COVID.

But viruses can also be used to benefit human health, agriculture and the environment.

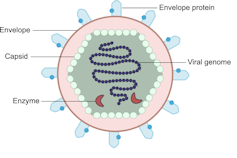

Viruses are comparatively simple in structure, consisting of a piece of genetic material (RNA or DNA) enclosed in a protein coat (the capsid). Some also have an outer envelope.

Viruses get into your cells and use your cell machinery to copy themselves.

Here are six ways we’ve harnessed this for health care and pest control.

1. To correct genes

Viruses are used in some gene therapies to correct malfunctioning genes. Genes are DNA sequences that code for a particular protein required for cell function.

If we remove viral genetic material from the capsid (protein coat) we can use the space to transport a “cargo” into cells. These modified viruses are called “viral vectors”.

DEXi

Viral vectors can deliver a functional gene into someone with a genetic disorder whose own gene is not working properly.

Some genetic diseases treated this way include haemophilia, sickle cell disease and beta thalassaemia.

2. Treat cancer

Viral vectors can be used to treat cancer.

Healthy people have p53, a tumour-suppressor gene. About half of cancers are associated with the loss of p53.

Replacing the damaged p53 gene using a viral vector stops the cancerous cell from replicating and tells it to suicide (apoptosis).

Viral vectors can also be used to deliver an inactive drug to a tumour, where it is then activated to kill the tumour cell.

This targeted therapy reduces the side effects otherwise seen with cytotoxic (cell-killing) drugs.

We can also use oncolytic (cancer cell-destroying) viruses to treat some types of cancer.

Tumour cells have often lost their antiviral defences. In the case of melanoma, a modified herpes simplex virus can kill rapidly dividing melanoma cells while largely leaving non-tumour cells alone.

3. Create immune responses

Viral vectors can create a protective immune response to a particular viral antigen.

One COVID vaccine uses a modified chimp adenovirus (adenoviruses cause the common cold in humans) to transport RNA coding for the SARS-CoV-2 spike protein into human cells.

The RNA is then used to make spike protein copies, which stimulate our immune cells to replicate and “remember” the spike protein.

Then, when you are exposed to SARS-CoV-2 for real, your immune system can churn out lots of antibodies and virus-killing cells very quickly to prevent or reduce the severity of infection.

4. Act as vaccines

Viruses can be modified to act directly as vaccines themselves in several ways.

We can weaken a virus (for an attenuated virus vaccine) so it doesn’t cause infection in a healthy host but can still replicate to stimulate the immune response. The chickenpox vaccine works like this.

The Salk vaccine for polio uses a whole virus that has been inactivated (so it can’t cause disease).

Others use a small part of the virus such as a capsid protein to stimulate an immune response (subunit vaccines).

An mRNA vaccine packages up viral RNA for a specific protein that will stimulate an immune response.

5. Kill bacteria

Viruses can – in limited situations in Australia – be used to treat antibiotic-resistant bacterial infections.

Bacteriophages are viruses that kill bacteria. Each type of phage usually infects a particular species of bacteria.

Unlike antibiotics – which often kill “good” bacteria along with the disease-causing ones – phage therapy leaves your normal flora (useful microbes) intact.

Shutterstock

6. Target plant, fungal or animal pests

Viruses can be species-specific (infecting one species only) and even cell-specific (infecting one type of cell only).

This occurs because the proteins viruses use to attach to cells have a shape that binds to a specific type of cell receptor or molecule, like a specific key fits a lock.

The virus can enter the cells of all species with this receptor/molecule. For example, rabies virus can infect all mammals because we share the right receptor, and mammals have other characteristics that allow infection to occur whereas other non-mammal species don’t.

When the receptor is only found on one cell type, then the virus will infect that cell type, which may only be found in one or a limited number of species. Hepatitis B virus successfully infects liver cells primarily in humans and chimps.

We can use that property of specificity to target invasive plant species (reducing the need for chemical herbicides) and pest insects (reducing the need for chemical insecticides). Baculoviruses, for example, are used to control caterpillars.

Similarly, bacteriophages can be used to control bacterial tomato and grapevine diseases.

Other viruses reduce plant damage from fungal pests.

Myxoma virus and calicivirus reduce rabbit populations and their environmental impacts and improve agricultural production.

Just like humans can be protected against by vaccination, plants can be “immunised” against a disease-causing virus by being exposed to a milder version.

Thea van de Mortel, Professor, Nursing, School of Nursing and Midwifery, Griffith University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Don’t Forget…

Did you arrive here from our newsletter? Don’t forget to return to the email to continue learning!

Recommended

Learn to Age Gracefully

Join the 98k+ American women taking control of their health & aging with our 100% free (and fun!) daily emails:

-

How to Eat to Change How You Drink – by Dr. Brooke Scheller

10almonds is reader-supported. We may, at no cost to you, receive a portion of sales if you purchase a product through a link in this article.

Whether you want to stop drinking or just cut down, this book can help. But what makes it different from the other reduce/stop drinking books we’ve reviewed?

Mostly, it’s about nutrition. This book focuses on the way that alcohol changes our relationship to food, our gut, our blood sugars, and more. The author also explains how reducing/stopping drinking, without bearing these things in mind, can be unnecessarily extra hard.

The remedy? To bear them in mind, of course, but that requires knowing them. So what she does is explain the physiology of what’s going on in terms of each of the above things (and more), and how to adjust your diet to make up for what alcohol has been doing to you, so that you can reduce/quit without feeling constantly terrible.

The style is very pop-science, light in tone, readable. She makes reference to a lot of hard science, but doesn’t discuss it in more depth than is necessary to convey the useful information. So, this is a practical book, aimed at all people who want to reduce/quit drinking.

Bottom line: if you feel like it’s hard to drink less because it feels like something is missing, it’s probably because indeed something is missing, and this book can help you bridge that gap!

Click here to check out How To Eat To Change How You Drink, and do just that!

Share This Post

-

The Age of Scientific Wellness – by Dr. Leroy Hood & Dr. Nathan Price

10almonds is reader-supported. We may, at no cost to you, receive a portion of sales if you purchase a product through a link in this article.

We don’t usually do an author bio beyond mentioning their professional background, but in this case it’s worth mentioning that the first-listed author, Dr. Leroy Hood, is the one who invented the automated gene sequencing technology that made the Human Genome Project possible. In terms of awards, he’s won everything short of a Nobel Prize, and that’s probably less a snub and more a matter of how there isn’t a Nobel Prize for Engineering—his field is molecular biotechnology, but what he solved was an engineering problem.

In this book, the authors set out to make the case that “find it and fix it” medicine has done a respectable job of getting us where we are, but what we need now is P4 medicine:

- Predict

- Prevent

- Personalize

- Participate

The idea is that with adequate data (genomic, phenomic, and digital), we can predict the course of health sufficiently well to interrupt the process of disease at its actual (previously unseen) starting point, instead of waiting for symptoms to show up, thus preventing it proactively. The personalization is because this will not be a “one size fits all” approach, since our physiologies are different, our markers of health and disease will be somewhat too. And the participatory aspect? That’s because the only way to get enough data to do this for an entire population is with—more or less—an entire population’s involvement.

This is what happens when, for example, your fitness tracker asks if it can share anonymized health metrics for research purposes and you allow it—you are becoming part of the science (a noble and worthy act!).

You may be wondering whether this book has health advice, or is more about the big picture. And, the answer is both. It’s mostly about the big picture but it does have a lot of (data-driven!) health advice too, especially towards the end.

The style is largely narrative, talking the reader through the progresses (and setbacks) that have marked the path so far, and projecting the next part of the journey, in the hope that we can avoid being part of a generation born just too late to take advantage of this revolutionary approach to health.

Bottom line: this isn’t a very light read, but it is a worthwhile one, and it’ll surely inspire you to increase the extent to which you are proactive about your health!

Click here to check out The Age Of Scientific Wellness, and be part of it!

Share This Post

-

Wondering how to spot the signs of postpartum depression?

10almonds is reader-supported. We may, at no cost to you, receive a portion of sales if you purchase a product through a link in this article.

Postpartum depression, or PPD, is a debilitating, potentially life-threatening mental health condition that impacts about one in eight people who give birth in the U.S. While it’s normal to feel worried or stressed after becoming a parent, PPD can cause feelings of extreme sadness or anxiety that may lead to suicidal thoughts.

Read on to learn what PPD is, what causes it, how it’s treated, and more.

What is the difference between the baby blues and postpartum depression?

Postpartum blues, or the “baby blues,” impact up to 80 percent of new parents. The baby blues may cause bouts of crying, mood swings, anxiety, sadness, reduced concentration, irritability, changes in appetite, and trouble sleeping, but symptoms are fleeting.

“Baby blues are a transient period—hours to a few days—of emotionality that does not impair one’s functioning or cause severe symptoms like suicidality,” says Dr. Jennifer L. Payne, a professor of psychiatry and neurobehavioral sciences at the University of Virginia. “[Postpartum depression] can cause severe symptoms, including suicidality.”

In addition to causing more debilitating symptoms, PPD can last for months.

Some new parents also experience postpartum psychosis, which can cause hallucinations and delusions. However, unlike PPD, postpartum psychosis is rare.

What are the symptoms of postpartum depression?

PPD symptoms may include:

- Feeling depressed, irritable, angry, or hopeless

- Severe mood swings

- Difficulty bonding with your baby

- Withdrawing from family and friends

- Changes in appetite or sleeping patterns

- Extreme fatigue

- Difficulty concentrating

- Anxiety and panic attacks

- Thoughts of harming yourself or your baby

- Thoughts of death or suicide

If you are experiencing symptoms of PPD, Payne recommends seeking help from a primary care provider or obstetrician right away.

“It’s really important—not just for you, but for your baby,” Payne explains. “Babies exposed to significant PPD have slower language development, lower IQs, and more behavioral problems.”

Your health care provider will ask you a series of screening questions to determine if you are experiencing PPD.

What causes postpartum depression?

Research suggests that the drop in hormones that occurs after birth, genetics, and sleep deprivation may contribute to PPD.

You may be at higher risk of developing PPD if you have a history of mental health conditions like depression or bipolar disorder, have relatives who’ve experienced PPD, or experienced stressful events during or after pregnancy.

How is postpartum depression treated?

“PPD is usually treated with antidepressant medications—typically SSRIs and now with the new FDA-approved medication, zuranolone,” says Payne. Therapy has also been shown to help people manage PPD.

Your health care provider can help determine the best treatment options for you and can outline the risks and benefits of taking certain medications while breastfeeding.

For referrals to care, information about local support groups, and other mental health resources for new parents, call the National Maternal Mental Health Hotline or Postpartum Support International. If you are experiencing a mental health emergency, call or text the 988 Suicide & Crisis Lifeline.

Can non-birthing parents have postpartum depression?

New parents who did not give birth, including cisgender men, may experience anxiety, depression, irritability, fatigue, and changes in appetite or sleeping patterns after a partner gives birth.

“Everyone knows that mothers’ hormones change a lot during and after pregnancy,” psychologist Scott Bea said in a 2019 Cleveland Clinic article. “But there’s evidence that fathers also experience real changes in their hormone levels after a baby is born.”

Adoptive parents may also show similar symptoms.

If you or anyone you know is considering suicide or self-harm or is anxious, depressed, upset, or needs to talk, call the Suicide & Crisis Lifeline at 988 or text the Crisis Text Line at 741-741. For international resources, here is a good place to begin.

This article first appeared on Public Good News and is republished here under a Creative Commons license.

Share This Post

Related Posts

-

Marathons in Mid- and Later-Life

10almonds is reader-supported. We may, at no cost to you, receive a portion of sales if you purchase a product through a link in this article.

It’s Q&A Day at 10almonds!

Have a question or a request? You can always hit “reply” to any of our emails, or use the feedback widget at the bottom!

In cases where we’ve already covered something, we might link to what we wrote before, but will always be happy to revisit any of our topics again in the future too—there’s always more to say!

As ever: if the question/request can be answered briefly, we’ll do it here in our Q&A Thursday edition. If not, we’ll make a main feature of it shortly afterwards!

So, no question/request too big or small

We had several requests pertaining to veganism, meatless mondays, and substitutions in recipes—so we’re going to cover those on a different day!

As for questions we’re answering today…

Q: Is there any data on immediate and long term effects of running marathons in one’s forties?

An interesting and very specific question! We didn’t find an overabundance of studies specifically for the short- and long-term effects of marathon-running in one’s 40s, but we did find a couple of relevant ones:

The first looked at marathon-runners of various ages, and found that…

- there are virtually no relevant running time differences (p<0.01) per age in marathon finishers from 20 to 55 years

- the majority of middle-aged and elderly athletes have training histories of less than seven years of running

From which they concluded:

❝The present findings strengthen the concept that considers aging as a biological process that can be considerably speeded up or slowed down by multiple lifestyle related factors.❞

See the study: Performance, training and lifestyle parameters of marathon runners aged 20–80 years: results of the PACE-study

The other looked specifically at the impact of running on cartilage, controlled for age (45 and under vs 46 and older) and activity level (marathon-runners vs sedentary people).

The study had the people, of various ages and habitual activity levels, run for 30 minutes, and measured their knee cartilage thickness (using MRI) before and after running.

They found that regardless of age or habitual activity level, running compressed the cartilage tissue to a similar extent. From this, it can be concluded that neither age nor marathon-running result in long-term changes to cartilage response to running.

Or in lay terms: there’s no reason that marathon-running at 40 should ruin your knees (unless you are doing something wrong).

That may or may not have been a concern you have, but it’s what the study looked at, so hey, it’s information.

Here’s the study: Functional cartilage MRI T2 mapping: evaluating the effect of age and training on knee cartilage response to running

Q: Information on [e-word] dysfunction for those who have negative reactions to [the most common medications]?

When it comes to that particular issue, one or more of these three factors are often involved:

- Hormones

- Circulation

- Psychology

The most common drugs (that we can’t name here) work on the circulation side of things—specifically, by increasing the localized blood pressure. The exact mechanism of this drug action is interesting, albeit beyond the scope of a quick answer here today. On the other hand, the way that they work can cause adverse blood-pressure-related side effects for some people; perhaps you’re one of them.

To take matters into your own hands, so to speak, you can address each of those three things we just mentioned:

Hormones

Ask your doctor (or a reputable phlebotomy service) for a hormone test. If your free/serum testosterone levels are low (which becomes increasingly common in men over the age of 45), they may prescribe something—such as testosterone shots—specifically for that.

This way, it treats the underlying cause, rather than offering a workaround like those common pills whose names we can’t mention here.

Circulation

Look after your heart health; eat for your heart health, and exercise regularly!

Cold showers/baths also work wonders for vascular tone—which is precisely what you need in this matter. By rapidly changing temperatures (such as by turning off the hot water for the last couple of minutes of your shower, or by plunging into a cold bath), your blood vessels will get practice at constricting and maintaining that constriction as necessary.

Psychology

[E-word] dysfunction can also have a psychological basis. Unfortunately, this can also then be self-reinforcing, if recalling previous difficulties causes you to get distracted/insecure and lose the moment. One of the best things you can do to get out of this catch-22 situation is to not worry about it in the moment. Depending on what you and your partner(s) like to do in bed, there are plenty of other equally respectable options, so just switch track!

Having a conversation about this in advance will probably be helpful, so that everyone’s on the same page of the script in that eventuality, and it becomes “no big deal”. Without that conversation, misunderstandings and insecurities could arise for your partner(s) as well as yourself (“aren’t I desirable enough?” etc).

So, to recap, we recommend:

- Have your hormones checked

- Look after your circulation

- Make the decision to have fun!

Don’t Forget…

Did you arrive here from our newsletter? Don’t forget to return to the email to continue learning!

Learn to Age Gracefully

Join the 98k+ American women taking control of their health & aging with our 100% free (and fun!) daily emails:

-

5 Ways to Beat Menopausal Weight Gain!

10almonds is reader-supported. We may, at no cost to you, receive a portion of sales if you purchase a product through a link in this article.

As it turns out, “common” does not mean “inevitable”!

Health Coach Kait’s advice

Her 5 tips are…

- Understand your metabolism: otherwise you’re working the dark and will get random results. Learn about how different foods affect your metabolism, and note that hormonal changes due to menopause can mean that some food types have different effects now.

- Eat enough protein: one thing doesn’t change—protein helps with satiety, thus helping to avoid overeating.

- Focus on sleep: prioritizing sleep is essential for hormone regulation, and that means not just sex hormones, but also food-related hormones such as insulin, ghrelin, and leptin.

- Be smart about carbs: taking a lot of carbs at once can lead to insulin spikes and thus metabolic disorder, which in turn leads to fat in places you don’t want it (especially your liver and belly). Enjoying a low-carb diet, and/or pairing your carbs with proteins and fats, does a lot to help avoid insulin spikes too. Not mentioned in the video, but we’re going to mention here: don’t underestimate fiber’s role either, especially if you take it before the carbs, which is best for blood sugars, as it gives a buffer to the digestive process, thus slowing down absorption of carbs.

- Build muscle: if trying to avoid/lose fat, it’s tempting to focus on cardio, but we generally can’t exercise our way out of having fat, whereas having more muscle increases the body’s metabolic base rate, burning fat just by existing. So for this reason, enjoy muscle-building resistance exercises at least a few times per week.

For more information on each of these, enjoy:

Click Here If The Embedded Video Doesn’t Load Automatically!

Want to learn more?

You might also like to read:

Visceral Belly Fat & How To Lose It

Take care!

Don’t Forget…

Did you arrive here from our newsletter? Don’t forget to return to the email to continue learning!

Learn to Age Gracefully

Join the 98k+ American women taking control of their health & aging with our 100% free (and fun!) daily emails:

-

Your Simplest Life – by Lisa Turner

10almonds is reader-supported. We may, at no cost to you, receive a portion of sales if you purchase a product through a link in this article.

We probably know how to declutter, and perhaps even do a “unnecessary financial expenditures” audit. So, what does this offer beyond that?

A large portion of this book focuses on keeping our general life in a state of “flow”, and strategies include:

- How to make sure you’re doing the right part of the 80:20 split on a daily basis

- Knowing when to switch tasks, and when not to

- Knowing how to plan time for tasks

- No more reckless optimism, but also without falling foul of Parkinson’s Law (i.e. work expands to fill the time allotted to it)

- Decluttering your head, too!

When it comes to managing life responsibilities in general, Turner is very attuned to generational differences… Including the different challenges faced by each generation, what’s more often expected of us, what we’re used to, and how we probably initially learned to do it (or not).

To this end, a lot of strategies are tailored with variations for each age group. Not often does an author take the time to address each part of their readership like that, and it’s really helpful that she does!

All in all, a great book for simplifying your daily life.

Don’t Forget…

Did you arrive here from our newsletter? Don’t forget to return to the email to continue learning!

Learn to Age Gracefully

Join the 98k+ American women taking control of their health & aging with our 100% free (and fun!) daily emails: