Tight Hamstrings? Here’s A Test To Know If It’s Actually Your Sciatic Nerve

10almonds is reader-supported. We may, at no cost to you, receive a portion of sales if you purchase a product through a link in this article.

Tight hamstrings are often not actually due to hamstring issues, but rather, are often being limited by the sciatic nerve. This video offers a home test to determine if the sciatic nerve is causing mobility problems (and how to improve it, if so):

The Connection

Try this test:

- Sit down with a slumped posture.

- Extend one leg with the ankle flexed.

- Note any stretching or pulling sensation behind the knee or in the calf.

- Bring your head down to your chest

If this increases the sensation, it likely indicates sciatic nerve involvement.

If only the hamstrings are tight, head movement won’t change the stretch sensation.

This is because the nervous system is a continuous structure, so head movement can affect nerve tension throughout the body. While this can cause problems, it can also be integral in the solution. Here are two ways:

- Flossing method: sit with “poor” slumped posture, extend the knee, keep the ankle flexed, and lift the head to relieve nerve tension. This movement helps the sciatic nerve slide without stretching it.

- Even easier method: lie on your back, grab behind the knee, and extend the leg while extending the neck. This position avoids compression in the gluteal area, making it suitable for severely compromised nerves. Perform the movement without significant stretching or pain.

In both cases: move gently to avoid straining the nerve, which can worsen muscle tension. Do 10 repetitions per leg, multiple times a day; after a week, increase to 20 reps.

A word of caution: speak with your doctor before trying these exercises if you have underlying neurological diseases, cut or infected nerves, or other severe conditions.

For more on all of this, plus visual demonstrations, enjoy:

Click Here If The Embedded Video Doesn’t Load Automatically!

Want to learn more?

You might also like to read:

Exercises for Sciatica Pain Relief

Take care!

Don’t Forget…

Did you arrive here from our newsletter? Don’t forget to return to the email to continue learning!

Recommended

Learn to Age Gracefully

Join the 98k+ American women taking control of their health & aging with our 100% free (and fun!) daily emails:

-

Foods For Managing Hypothyroidism (incl. Hashimoto’s)

10almonds is reader-supported. We may, at no cost to you, receive a portion of sales if you purchase a product through a link in this article.

Foods for Managing Hypothyroidism

For any unfamiliar, hypothyroidism is the condition of having an underactive thyroid gland. The thyroid gland lives at the base of the front of your neck, and, as the name suggests, it makes and stores thyroid hormones. Those are important for many systems in the body, and a shortage typically causes fatigue, weight gain, and other symptoms.

What causes it?

This makes a difference in some cases to how it can be treated/managed. Causes include:

- Hashimoto’s thyroiditis, an autoimmune condition

- Severe inflammation (end result is similar to the above, but more treatable)

- Dietary deficiencies, especially iodine deficiency

- Secondary endocrine issues, e.g. pituitary gland didn’t make enough TSH for the thyroid gland to do its thing

- Some medications (ask your pharmacist)

We can’t do a lot about those last two by leveraging diet alone, but we can make a big difference to the others.

What to eat (and what to avoid)

There is nuance here, which we’ll go into a bit, but let’s start by giving the

one-linetwo-line summary that tends to be the dietary advice for most things:- Eat a nutrient-dense whole-foods diet (shocking, we know)

- Avoid sugar, alcohol, flour, processed foods (ditto)

What’s the deal with meat and dairy?

- Meat: avoid red and processed meats; poultry and fish are fine or even good (unless fried; don’t do that)

- Dairy: limit/avoid milk; but unsweetened yogurt and cheese are fine or even good

What’s the deal with plants?

First, get plenty of fiber, because that’s important to ease almost any inflammation-related condition, and for general good health for most people (an exception is if you have Crohn’s Disease, for example).

If you have Hashimoto’s, then gluten (as found in wheat, barley, and rye) may be an issue, but the jury is still out, science-wise. Here’s an example study for “avoid gluten” and “don’t worry about gluten”, respectively:

- The Effect of Gluten-Free Diet on Thyroid Autoimmunity in Women with Hashimoto’s Thyroiditis

- Doubtful Justification of the Gluten-Free Diet in the Course of Hashimoto’s Disease

So, you might want to skip it, to be on the safe side, but that’s up to you (and the advice of your nutritionist/doctor, as applicable).

A word on goitrogens…

Goitrogens are found in cruciferous vegetables and soy, both of which are very healthy foods for most people, but need some extra awareness in the case of hypothyroidism. This means there’s no need to abstain completely, but:

- Keep serving sizes small, for example a 100g serving only

- Cook goitrogenic foods before eating them, to greatly reduce goitrogenic activity

For more details, reading even just the abstract (intro summary) of this paper will help you get healthy cruciferous veg content without having a goitrogenic effect.

(as for soy, consider just skipping that if you suffer from hypothyroidism)

What nutrients to focus on getting?

- Top tier nutrients: iodine, selenium, zinc

- Also important: vitamin B12, vitamin D, magnesium, iron

Enjoy!

Share This Post

-

Paving The Way To Good Health

10almonds is reader-supported. We may, at no cost to you, receive a portion of sales if you purchase a product through a link in this article.

This is Dr. Michelle Tollefson. She’s a gynecologist, and a menopause and lifestyle medicine expert. She’s also a breast cancer survivor, and, indeed, thriver.

So, what does she want us to know?

A Multivector Approach To Health

There’s a joke that goes: a man is trapped in a flooding area, and as the floodwaters rise, he gets worried and begins to pray, but he is interrupted when some people come by on a raft and offer him to go with them. He looks at the rickety raft and says “No, you go on, God will spare me”. He returns to his prayer, and is further interrupted by a boat and finally a helicopter, and each time he gives the same response. He drowns, and in the afterlife he asks God “why didn’t you spare me from the flood?”, and God replies “I sent a raft, a boat, and a helicopter; what more did you want?!”

People can be a bit the same when it comes to different approaches to cancer and other serious illness. They are offered chemotherapy and say “No, thank you, eating fruit will spare me”.

Now, this is not to trivialize those who decline aggressive cancer treatments for other reasons such as “I am old and would rather not go through that; I’d rather have a shorter life without chemo than a longer life with it”—for many people that’s a valid choice.

But it is to say: lifestyle medicine is, mostly, complementary medicine.

It can be very powerful! It can make the difference between life and death! Especially when it comes to things like cancer, diabetes, heart disease, etc.

But it’s not a reason to decline powerful medical treatments if/when those are appropriate. For example, in Dr. Tollefson’s case…

Synergistic health

Dr. Tollefson, herself a lifestyle medicine practitioner and gynecologist (and having thus done thousands of clinical breast exams for other people, screening for breast cancer), says she owes her breast cancer survival to two things, or rather two categories of things:

- a whole-food, plant predominant diet, daily physical activity, prioritizing sleep, minimizing stress, and a strong social network

- a bilateral mastectomy, 16 rounds of chemotherapy, removal of her ovaries, and several reconstructive surgeries

Now, one may wonder: if the first thing is so good, why need the second?

Or on the flipside: if the second thing was necessary, what was the point of the first?

And the answer she gives is: the first thing was the reason she was able to make it through the second thing.

And on the next level: the second thing was the reason she’s still around to talk about the first thing.

In other words: she couldn’t have done it with just one or the other.

A lot of medicine in general, and lifestyle medicine in particular, is like this. If we note that such-and-such a thing decreases our risk of cancer mortality by 4%, that’s a small decrease, but it can add up (and compound!) if it’s surrounded by other things that also each decrease the risk by 12%, 8%, 15%, and so on.

Nor is this only confined to cancer, nor only to the positives.

Let’s take cardiovascular disease: if a person smokes, drinks, eats red meat, stresses, and has a wild sleep schedule, you can imagine those risk factors add up and compound.

If this person and another with a heart-healthy lifestyle both have a stroke (it can happen to anyone, even if it’s less likely in this case), and both need treatment, then two things are true:

- They are both still going to need treatment (medicines, and possibly a thrombectomy)

- The second person is most likely to recover, and most likely to recover more quickly and easily

The second person can be said to have paved the way to their recovery, with their lifestyle.

Which is really important, because a lot of people think “what’s the point in living so healthily if [disease] strikes anyway?” and the answer is:

A very large portion of your recovery is predicated on how you lived your life before The Bad Thing™ happened, and that can be the difference between bouncing back quickly and a long struggle back to health.

Or the difference between a long struggle back to health, or a short struggle followed by rapid decline and death.

In short:

Play the odds, improve your chances with lifestyle medicine. Enjoy those cancer-fighting fruits:

Top 8 Fruits That Prevent & Kill Cancer

…but also, get your various bits checked when appropriate; we know, mammograms and prostate checks etc are not usually the highlight of most people’s days, but they save lives. And if it turns out you need serious medical interventions, consider them seriously.

And, by all means, enjoy mood-boosting nutraceuticals such as:

12 Foods That Fight Depression & Anxiety

…but also recognize that sometimes, your brain might have an ongoing biochemical problem that a tablespoon of pumpkin seeds isn’t going to fix.

And absolutely, you can make lifestyle adjustments to reduce the risks associated with menopause, for example:

Menopause, & How Lifestyle Continues To Matter “Postmenopause”

…but also be aware that if the problem is “not enough estrogen”, sometimes to solution is “take estrogen”.

And so on.

Want to know Dr. Tollefson’s lifestyle recommendations?

Most of them will not be a surprise to you, and we mentioned some of them above (a whole-food, plant predominant diet, daily physical activity, prioritizing sleep, minimizing stress, and a strong social network), but for more specific recommendations, including numbers etc, enjoy:

Click Here If The Embedded Video Doesn’t Load Automatically!

Take care!

Share This Post

-

Never Too Old?

10almonds is reader-supported. We may, at no cost to you, receive a portion of sales if you purchase a product through a link in this article.

Age Limits On Exercise?

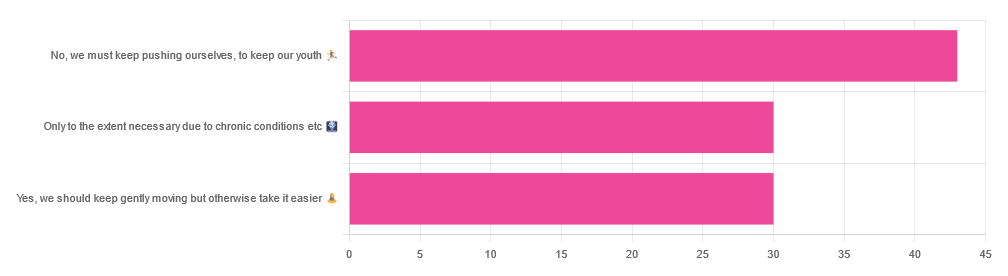

In Tuesday’s newsletter, we asked you your opinion on whether we should exercise less as we get older, and got the above-depicted, below-described, set of responses:

- About 42% said “No, we must keep pushing ourselves, to keep our youth“

- About 29% said “Only to the extent necessary due to chronic conditions etc”

- About 29% said “Yes, we should keep gently moving but otherwise take it easier”

One subscriber who voted for “No, we must keep pushing ourselves, to keep our youth“ wrote to add:

❝I’m 71 and I push myself. I’m not as fast or strong as I used to be but, I feel great when I push myself instead of going through the motions. I listen to my body!❞

~ 10almonds subscriber

One subscriber who voted for “Only to the extent necessary due to chronic conditions etc” wrote to add:

❝It’s never too late to get stronger. Important to keep your strength and balance. I am a Silver Sneakers instructor and I see first hand how helpful regular exercise is for seniors.❞

~ 10almonds subscriber

One subscriber who voted to say “Yes, we should keep gently moving but otherwise take it easier” wrote to add:

❝Keep moving but be considerate and respectful of your aging body. It’s a time to find balance in life and not put yourself into a positon to damage youself by competing with decades younger folks (unless you want to) – it will take much longer to bounce back.❞

~ 10almonds subscriber

These will be important, because we’ll come back to them at the end.

So what does the science say?

Endurance exercise is for young people only: True or False?

False! With proper training, age is no barrier to serious endurance exercise.

Here’s a study that looked at marathon-runners of various ages, and found that…

- the majority of middle-aged and elderly athletes have training histories of less than seven years of running

- there are virtually no relevant running time differences (p<0.01) per age in marathon finishers from 20 to 55 years

- after 55 years, running times did increase on average, but not consistently (i.e. there were still older runners with comparable times to the younger age bracket)

The researchers took this as evidence of aging being indeed a biological process that can be sped up or slowed down by various lifestyle factors.

See also:

Age & Aging: What Can (And Can’t) We Do About It?

this covers the many aspects of biological aging (it’s not one number, but many!) and how our various different biological ages are often not in sync with each other, and how we can optimize each of them that can be optimized

Resistance training is for young people only: True or False?

False! In fact, it’s not only possible for older people, but is also associated with a reduction in all-cause mortality.

Specifically, those who reported strength-training at least once per week enjoyed longer lives than those who did not.

You may be thinking “is this just the horse-riding thing again, where correlation is not causation and it’s just that healthier people (for other reasons) were able to do strength-training more, rather than the other way around?“

…which is a good think to think of, so well-spotted if you were thinking that!

But in this case no; the benefits remained when other things were controlled for:

❝Adjusted for demographic variables, health behaviors and health conditions, a statistically significant effect on mortality remained.

Although the effects on cardiac and cancer mortality were no longer statistically significant, the data still pointed to a benefit.

Importantly, after the physical activity level was controlled for, people who reported strength exercises appeared to see a greater mortality benefit than those who reported physical activity alone.❞

See the study: Is strength training associated with mortality benefits? A 15 year cohort study of US older adults

And a pop-sci article about it: Strength training helps older adults live longer

Closing thoughts

As it happens… All three of the subscribers we quoted all had excellent points!

Because in this case it’s less a matter of “should”, and more a selection of options:

- We (most of us, at least) can gain/regain/maintain the kind of strength and fitness associated with much younger people, and we need not be afraid of exercising accordingly (assuming having worked up to such, not just going straight from couch to marathon, say).

- We must nevertheless be mindful of chronic conditions or even passing illnesses/injuries, but that goes for people of any age

- We also can’t argue against a “safety first” cautious approach to exercise. After all, sure, maybe we can run marathons at any age, but that doesn’t mean we have to. And sure, maybe we can train to lift heavy weights, but if we’re content to be able to carry the groceries or perhaps take our partner’s weight in the dance hall (or the bedroom!), then (if we’re also at least maintaining our bones and muscles at a healthy level) that’s good enough already.

Which prompts the question, what do you want to be able to do, now and years from now? What’s important to you?

For inspiration, check out: Train For The Event Of Your Life!

Take care!

Share This Post

Related Posts

-

What should I do if I can’t see a psychiatrist?

10almonds is reader-supported. We may, at no cost to you, receive a portion of sales if you purchase a product through a link in this article.

People presenting at emergency with mental health concerns are experiencing the longest wait times in Australia for admission to a ward, according to a new report from the Australasian College of Emergency Medicine.

But with half of New South Wales’ public psychiatrists set to resign next week after ongoing pay disputes – and amid national shortages in the mental health workforce – Australians who rely on psychiatry support may be wondering where else to go.

If you can’t get in to see a psychiatrist and you need help, there are some other options. However in an emergency, you should call 000.

Why do people see a psychiatrist?

Psychiatrists are doctors who specialise in mental health and can prescribe medication.

People seek or require psychiatry support for many reasons. These may include:

- severe depression, including suicidal thoughts or behaviours

- severe anxiety, panic attacks or phobias

- post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD)

- eating disorders, such as anorexia or bulimia

- attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD).

Psychiatrists complement other mental health clinicians by prescribing certain medications and making decisions about hospital admission. But when psychiatry support is not available a range of team members can contribute to a person’s mental health care.

Can my GP help?

Depending on your mental health concerns, your GP may be able to offer alternatives while you await formal psychiatry care.

GPs provide support for a range of mental health concerns, regardless of formal diagnosis. They can help address the causes and impact of issues including mental distress, changes in sleep, thinking, mood or behaviour.

The GP Psychiatry Support Line also provides doctors advice on care, prescription medication and how support can work.

It’s a good idea to book a long consult and consider taking a trusted person. Be explicit about how you’ve been feeling and what previous supports or medication you’ve accessed.

What about psychologists, counsellors or community services?

Your GP should also be aware of supports available locally and online.

For example, Head to Health is a government initiative, including information, a nationwide phone line, and in-person clinics in Victoria. It aims to improve mental health advice, assessment and access to treatment.

Medicare Mental Health Centres provide in-person care and are expanding across Australia.

There are also virtual care services in some areas. This includes advice on individualised assessment including whether to go to hospital.

Some community groups are led by peers rather than clinicians, such as Alternatives to Suicide.

How about if I’m rural or regional?

Accessing support in rural or regional areas is particularly tough.

Beyond helplines and formal supports, other options include local Suicide Prevention Networks and community initiatives such as ifarmwell and Men’s sheds.

Should I go to emergency?

As the new report shows, people who present at hospital emergency departments for mental health should expect long wait times before being admitted to a ward.

But going to a hospital emergency department will be essential for some who are experiencing a physical or mental health crisis.

Managing suicide-related distress

With the mass resignation of NSW psychiatrists looming, and amid shortages and blown-out emergency waiting times, people in suicide-related distress must receive the best available care and support.

Roughly nine Australians die by suicide each day. One in six have had thoughts of suicide at some point in their lives.

Suicidal thoughts can pass. There are evidence-based strategies people can immediately turn to when distressed and in need of ongoing care.

Safety planning is a popular suicide prevention strategy to help you stay safe.

What is a safety plan?

This is a personalised, step-by-step plan to remain safe during the onset or worsening of suicidal urges.

You can develop a safety plan collaboratively with a clinician and/or peer worker, or with loved ones. You can also make one on your own – many people like to use the Beyond Now app.

Safety plans usually include:

- recognising personal warning signs of a crisis (for example, feeling like a burden)

- identifying and using internal coping strategies (such as distracting yourself by listening to favourite music)

- seeking social supports for distraction (for example, visiting your local library)

- letting trusted family or friends know how you’re feeling – ideally, they should know they’re in your safety plan

- knowing contact details of specific mental health services (your GP, mental health supports, local hospital)

- making the environment safer by removing or limiting access to lethal means

- identifying specific and personalised reasons for living.

Our research shows safety planning is linked to reduced suicidal thoughts and behaviour, as well as feelings of depression and hopelessness, among adults.

Evidence from people with lived experience shows safety planning helps people to understand their warning signs and practice coping strategies.

Sharing your safety plan with loved ones may help understand warning signs of a crisis. Dragana Gordic/Shutterstock Are there helplines I can call?

There are people ready to listen, by phone or online chat, Australia-wide. You can try any of the following (most are available 24 hours a day, seven days a week):

Suicide helplines:

- Lifeline 13 11 14

- Suicide Call Back Service 1300 659 467

There is also specialised support:

- for men: MensLine Australia 1300 78 99 78

- children and young people: Kids’ Helpline 1800 55 1800

- Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people: 13YARN 13 92 76

- veterans and their families: Open Arms 1800 011 046

- LGBTQIA+ community: QLife 1300 184 527

- new and expecting parents: PANDA 1300 726 306

- people experiencing eating disorders: Butterfly Foundation 1800 33 4673.

Additionally, each state and territory will have its own list of mental health resources.

With uncertain access to services, it’s helpful to remember that there are people who care. You don’t have to go it alone.

Monika Ferguson, Senior Lecturer in Mental Health, University of South Australia and Nicholas Procter, Professor and Chair: Mental Health Nursing, University of South Australia

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Don’t Forget…

Did you arrive here from our newsletter? Don’t forget to return to the email to continue learning!

Learn to Age Gracefully

Join the 98k+ American women taking control of their health & aging with our 100% free (and fun!) daily emails:

-

What is PMDD?

10almonds is reader-supported. We may, at no cost to you, receive a portion of sales if you purchase a product through a link in this article.

Premenstrual dysphoric disorder (PMDD) is a mood disorder that causes significant mental health changes and physical symptoms leading up to each menstrual period.

Unlike premenstrual syndrome (PMS), which affects approximately three out of four menstruating people, only 3 percent to 8 percent of menstruating people have PMDD. However, some researchers believe the condition is underdiagnosed, as it was only recently recognized as a medical diagnosis by the World Health Organization.

Read on to learn more about its symptoms, the difference between PMS and PMDD, treatment options, and more.

What are the symptoms of PMDD?

People with PMDD typically experience both mood changes and physical symptoms during each menstrual cycle’s luteal phase—the time between ovulation and menstruation. These symptoms typically last seven to 14 days and resolve when menstruation begins.

Mood symptoms may include:

- Irritability

- Anxiety and panic attacks

- Extreme or sudden mood shifts

- Difficulty concentrating

- Depression and suicidal ideation

Physical symptoms may include:

- Fatigue

- Insomnia

- Headaches

- Changes in appetite

- Body aches

- Bloating

- Abdominal cramps

- Breast swelling or tenderness

What is the difference between PMS and PMDD?

Both PMS and PMDD cause emotional and physical symptoms before menstruation. Unlike PMS, PMDD causes extreme mood changes that disrupt daily life and may lead to conflict with friends, family, partners, and coworkers. Additionally, symptoms may last longer than PMS symptoms.

In severe cases, PMDD may lead to depression or suicide. More than 70 percent of people with the condition have actively thought about suicide, and 34 percent have attempted it.

What is the history of PMDD?

PMDD wasn’t added to the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders until 2013. In 2019, the World Health Organization officially recognized it as a medical diagnosis.

References to PMDD in medical literature date back to the 1960s, but defining it as a mental health and medical condition initially faced pushback from women’s rights groups. These groups were concerned that recognizing the condition could perpetuate stereotypes about women’s mental health and capabilities before and during menstruation.

Today, many women-led organizations are supportive of PMDD being an official diagnosis, as this has helped those living with the condition access care.

What causes PMDD?

Researchers don’t know exactly what causes PMDD. Many speculate that people with the condition have an abnormal response to fluctuations in hormones and serotonin—a brain chemical impacting mood— that occur throughout the menstrual cycle. Symptoms fully resolve after menopause.

People who have a family history of premenstrual symptoms and mood disorders or have a personal history of traumatic life events may be at higher risk of PMDD.

How is PMDD diagnosed?

Health care providers of many types, including mental health providers, can diagnose PMDD. Providers typically ask patients about their premenstrual symptoms and the amount of stress those symptoms are causing. Some providers may ask patients to track their periods and symptoms for one month or longer to determine whether those symptoms are linked to their menstrual cycle.

Some patients may struggle to receive a PMDD diagnosis, as some providers may lack knowledge about the condition. If your provider is unfamiliar with the condition and unwilling to explore treatment options, find a provider who can offer adequate support. The International Association for Premenstrual Disorders offers a directory of providers who treat the condition.

How is PMDD treated?

There is no cure for PMDD, but health care providers can prescribe medication to help manage symptoms. Some medication options include:

- Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs), a class of antidepressants that regulate serotonin in the brain and may improve mood when taken daily or during the luteal phase of each menstrual cycle.

- Hormonal birth control to prevent ovulation-related hormonal changes.

- Over-the-counter pain medication like Tylenol, which can ease headaches, breast tenderness, abdominal cramping, and other physical symptoms.

Providers may also encourage patients to make lifestyle changes to improve symptoms. Those lifestyle changes may include:

- Limiting caffeine intake

- Eating meals regularly to balance blood sugar

- Exercising regularly

- Practicing stress management using breathing exercises and meditation

- Having regular therapy sessions and attending peer support groups

For more information, talk to your health care provider.

If you or anyone you know is considering suicide or self-harm or is anxious, depressed, upset, or needs to talk, call the Suicide & Crisis Lifeline at 988 or text the Crisis Text Line at 741-741. For international resources, here is a good place to begin.

This article first appeared on Public Good News and is republished here under a Creative Commons license.

Don’t Forget…

Did you arrive here from our newsletter? Don’t forget to return to the email to continue learning!

Learn to Age Gracefully

Join the 98k+ American women taking control of their health & aging with our 100% free (and fun!) daily emails:

-

What are plyometric exercises? How all that hopping and jumping builds strength, speed and power

10almonds is reader-supported. We may, at no cost to you, receive a portion of sales if you purchase a product through a link in this article.

If you’ve ever seen people at the gym or the park jumping, hopping or hurling weighted balls to the ground, chances are they were doing plyometric exercises.

Examples include:

- box jumps, where you repeatedly leap quickly on and off a box

- lateral skater hops, where you bound from side to side like a speeding ice skater

- rapidly throwing a heavy medicine ball against a wall, or to the ground

- single leg hops, which may involve hopping on the spot or through an obstacle course

- squat jumps, where you repeatedly squat and then launch yourself into the air.

Photo by cottonbro studio/Pexels There are many more examples of plyometric exercises.

What ties all these moves together is that they use what’s known as the “stretch shortening cycle”. This is where your muscles rapidly stretch and then contract.

Runners routinely practise plyometric exercises to improve explosive leg strength. WoodysPhotos/Shutterstock Potential benefits

Research shows incorporating plyometric exercise into your routine can help you:

- jump higher

- sprint faster

- reduce the chances of getting a serious sporting injuries such as anterior cruciate ligament (ACL) tears

- build muscle strength

- improve bone mineral density (especially when combined with resistance training such as weight lifting), which is particularly important for women and older people at risk of falls.

Studies have found plyometric exercises can help:

- older people who want to retain and build muscle strength, boost bone health, improve posture and reduce the risk of falls

- adolescent athletes who want to build the explosive strength needed to excel in sports such as athletics, tennis, soccer, basketball and football

- female athletes who want to jump higher or change direction quickly (a useful skill in many sports)

- endurance runners who want to boost physical fitness, run time and athletic performance.

And when it comes to plyometric exercises, you get out what you put in.

Research has found the benefits of plyometrics are significantly greater when every jump was performed with maximum effort.

Jumping can help boost bone strength. WoodysPhotos/Shutterstock Potential risks

All exercise comes with risk (as does not doing enough exercise!)

Plyometrics are high-intensity activities that require the body to absorb a lot of impact when landing on the ground or catching medicine balls.

That means there is some risk of musculoskeletal injury, particularly if the combination of intensity, frequency and volume is too high.

You might miss a landing and fall, land in a weird way and crunch your ankle, or get a muscle tear if you’re overdoing it.

The National Strength and Conditioning Association, a US educational nonprofit that uses research to support coaches and athletes, recommends:

- a maximum of one to three plyometric sessions per week

- five to ten repetitions per set and

- rest periods of one to three minutes between sets to ensure complete muscle recovery.

With the right guidance, jumps can be safe for older people and may help reduce the risk of falls as you age. Realstock/Shutterstock One meta-analysis, where researchers looked at many studies, found plyometric training was feasible and safe, and could improve older people’s performance, function and health.

Overall, with appropriate programming and supervision, plyometric exercise can be a safe and effective way to boost your health and athletic performance.

Justin Keogh, Associate Dean of Research, Faculty of Health Sciences and Medicine, Bond University and Mandy Hagstrom, Senior Lecturer, Exercise Physiology. School of Health Sciences, UNSW Sydney

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Don’t Forget…

Did you arrive here from our newsletter? Don’t forget to return to the email to continue learning!

Learn to Age Gracefully

Join the 98k+ American women taking control of their health & aging with our 100% free (and fun!) daily emails: