Surgery is the default treatment for ACL injuries in Australia. But it’s not the only way

10almonds is reader-supported. We may, at no cost to you, receive a portion of sales if you purchase a product through a link in this article.

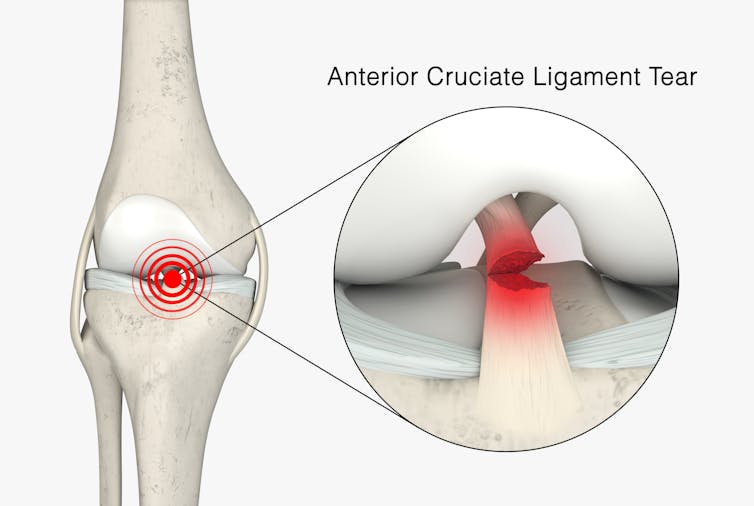

The anterior cruciate ligament (ACL) is an important ligament in the knee. It runs from the thigh bone (femur) to the shin bone (tibia) and helps stabilise the knee joint.

Injuries to the ACL, often called a “tear” or a “rupture”, are common in sport. While a ruptured ACL has just sidelined another Matildas star, people who play sport recreationally are also at risk of this injury.

For decades, surgical repair of an ACL injury, called a reconstruction, has been the primary treatment in Australia. In fact, Australia has among the highest rates of ACL surgery in the world. Reports indicate 90% of people who rupture their ACL go under the knife.

Although surgery is common – around one million are performed worldwide each year – and seems to be the default treatment for ACL injuries in Australia, it may not be required for everyone.

What does the research say?

We know ACL ruptures can be treated using reconstructive surgery, but research continues to suggest they can also be treated with rehabilitation alone for many people.

Almost 15 years ago a randomised clinical trial published in the New England Journal of Medicine compared early surgery to rehabilitation with the option of delayed surgery in young active adults with an ACL injury. Over half of people in the rehabilitation group did not end up having surgery. After five years, knee function did not differ between treatment groups.

The findings of this initial trial have been supported by more research since. A review of three trials published in 2022 found delaying surgery and trialling rehabilitation leads to similar outcomes to early surgery.

A 2023 study followed up patients who received rehabilitation without surgery. It showed one in three had evidence of ACL healing on an MRI after two years. There was also evidence of improved knee-related quality of life in those with signs of ACL healing compared to those whose ACL did not show signs of healing.

Regardless of treatment choice the rehabilitation process following ACL rupture is lengthy. It usually involves a minimum of nine months of progressive rehabilitation performed a few days per week. The length of time for rehabilitation may be slightly shorter in those not undergoing surgery, but more research is needed in this area.

Rehabilitation starts with a physiotherapist overseeing simple exercises right through to resistance exercises and dynamic movements such as jumping, hopping and agility drills.

A person can start rehabilitation with the option of having surgery later if the knee remains unstable. A common sign of instability is the knee giving way when changing direction while running or playing sports.

To rehab and wait, or to go straight under the knife?

There are a number of reasons patients and clinicians may opt for early surgical reconstruction.

For elite athletes, a key consideration is returning to sport as soon as possible. As surgery is a well established method, athletes (such as Matilda Sam Kerr) often opt for early surgical reconstruction as this gives them a more predictable timeline for recovery.

At the same time, there are risks to consider when rushing back to sport after ACL reconstruction. Re-injury of the ACL is very common. For every month return to sport is delayed until nine months after ACL reconstruction, the rate of knee re-injury is reduced by 51%.

Historically, another reason for having early surgical reconstruction was to reduce the risk of future knee osteoarthritis, which increases following an ACL injury. But a review showed ACL reconstruction doesn’t reduce the risk of knee osteoarthritis in the long term compared with non-surgical treatment.

That said, there’s a need for more high-quality, long-term studies to give us a better understanding of how knee osteoarthritis risk is influenced by different treatments.

Rehab may not be the only non-surgical option

Last year, a study looking at 80 people fitted with a specialised knee brace for 12 weeks found 90% had evidence of ACL healing on their follow-up MRI.

People with more ACL healing on the three-month MRI reported better outcomes at 12 months, including higher rates of returning to their pre-injury level of sport and better knee function. Although promising, we now need comparative research to evaluate whether this method can achieve similar results to surgery.

What to do if you rupture your ACL

First, it’s important to seek a comprehensive medical assessment from either a sports physiotherapist, sports physician or orthopaedic surgeon. ACL injuries can also have associated injuries to surrounding ligaments and cartilage which may influence treatment decisions.

In terms of treatment, discuss with your clinician the pros and cons of management options and whether surgery is necessary. Often, patients don’t know not having surgery is an option.

Surgery appears to be necessary for some people to achieve a stable knee. But it may not be necessary in every case, so many patients may wish to try rehabilitation in the first instance where appropriate.

As always, prevention is key. Research has shown more than half of ACL injuries can be prevented by incorporating prevention strategies. This involves performing specific exercises to strengthen muscles in the legs, and improve movement control and landing technique.

Anthony Nasser, Senior Lecturer in Physiotherapy, University of Technology Sydney; Joshua Pate, Senior Lecturer in Physiotherapy, University of Technology Sydney, and Peter Stubbs, Senior Lecturer in Physiotherapy, University of Technology Sydney

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Don’t Forget…

Did you arrive here from our newsletter? Don’t forget to return to the email to continue learning!

Recommended

Learn to Age Gracefully

Join the 98k+ American women taking control of their health & aging with our 100% free (and fun!) daily emails:

-

How Jumping Rope Changes The Human Body

10almonds is reader-supported. We may, at no cost to you, receive a portion of sales if you purchase a product through a link in this article.

Most popularly enjoyed by professional boxers and six-year-old girls, jumping rope is one of the most metabolism-boosting exercises around:

Just a hop, skip, and a jump away from good health

Maybe you haven’t tried it since your age was in single digits, so, if you do…

What benefits can you expect?

- Improves cardiovascular fitness, equivalent to 30 minutes of running with just 10 minutes of jumping.

- Increases bone density and boosts immunity by aiding the lymphatic system.

- Enhances explosiveness in the lower body, agility, and stamina.

- Improves shoulder endurance, coordination, and spatial awareness.

What kind of rope is best for you?

- Beginner ropes: licorice ropes (nylon/vinyl), beaded ropes for rhythm and durability.

- Advanced ropes: speed ropes (denser, faster materials) for higher speeds and more difficult skills.

- Weighted ropes: build upper body muscles (forearms, shoulders, chest, back).

What length should you get?

- Recommended rope length varies by height (8 ft for 5’0″–5’4″, 9 ft for 5’5″–5’11”, 10 ft for 6’0″ and above).

- Beginners should start with longer ropes for clearance.

What should you learn?

- Initial jump rope skills: start with manageable daily jump totals, gradually increasing as ankles, calves, and feet adapt.

- Further skills: learn the two-foot jump and then the boxer’s skip for efficient, longer sessions and advanced skills. Keep arms close and hands at waist level for a smooth swing.

For more on all of this, enjoy:

Click Here If The Embedded Video Doesn’t Load Automatically!

Want to learn more?

You might also like to read:

How To Do High Intensity Interval Training (Without Wrecking Your Body)

Take care!

Share This Post

-

Women’s Strength Training Anatomy – by Frédéric Delavier

10almonds is reader-supported. We may, at no cost to you, receive a portion of sales if you purchase a product through a link in this article.

Fitness guides for women tend to differ from fitness guides for men, in the wrong ways:

“Do some squats and jumping jacks, and here’s a exercise for your abs; you too can look like our model here”

In those other books we are left wonder: where’s the underlying information? Where are the explanations that aren’t condescending? Where, dare we ask, is the understanding that a woman might ever lift something heavier than a baby?

Delavier, in contrast, delivers. With 130 pages of detailed anatomical diagrams for all kinds of exercises to genuinely craft your body the way you want it for you. Bigger here, smaller there, functional strength, you decide.

And rest assured: no, you won’t end up looking like Arnold Schwarzenegger unless you not only eat like him, but also have his genes (and possibly his, uh, “supplement” regime).

What you will get though, is a deep understanding of how to tailor your exercise routine to actually deliver the personalized and specific results that you want.

Pick Up Today’s Book on Amazon!

Not looking for a feminine figure? You may like the same author’s book for men:

Share This Post

-

The Path to a Better Tuberculosis Vaccine Runs Through Montana

10almonds is reader-supported. We may, at no cost to you, receive a portion of sales if you purchase a product through a link in this article.

A team of Montana researchers is playing a key role in the development of a more effective vaccine against tuberculosis, an infectious disease that has killed more people than any other.

The BCG (Bacille Calmette-Guérin) vaccine, created in 1921, remains the sole TB vaccine. While it is 40% to 80% effective in young children, its efficacy is very low in adolescents and adults, leading to a worldwide push to create a more powerful vaccine.

One effort is underway at the University of Montana Center for Translational Medicine. The center specializes in improving and creating vaccines by adding what are called novel adjuvants. An adjuvant is a substance included in the vaccine, such as fat molecules or aluminum salts, that enhances the immune response, and novel adjuvants are those that have not yet been used in humans. Scientists are finding that adjuvants make for stronger, more precise, and more durable immunity than antigens, which create antibodies, would alone.

Eliciting specific responses from the immune system and deepening and broadening the response with adjuvants is known as precision vaccination. “It’s not one-size-fits-all,” said Ofer Levy, a professor of pediatrics at Harvard University and the head of the Precision Vaccines Program at Boston Children’s Hospital. “A vaccine might work differently in a newborn versus an older adult and a middle-aged person.”

The ultimate precision vaccine, said Levy, would be lifelong protection from a disease with one jab. “A single-shot protection against influenza or a single-shot protection against covid, that would be the holy grail,” Levy said.

Jay Evans, the director of the University of Montana center and the chief scientific and strategy officer and a co-founder of Inimmune, a privately held biotechnology company in Missoula, said his team has been working on a TB vaccine for 15 years. The private-public partnership is developing vaccines and trying to improve existing vaccines, and he said it’s still five years off before the TB vaccine might be distributed widely.

It has not gone unnoticed at the center that this state-of-the-art vaccine research and production is located in a state that passed one of the nation’s most extreme anti-vaccination laws during the pandemic in 2021. The law prohibits businesses and governments from discriminating against people who aren’t vaccinated against covid-19 or other diseases, effectively banning both public and private employers from requiring workers to get vaccinated against covid or any other disease. A federal judge later ruled that the law cannot be enforced in health care settings, such as hospitals and doctors’ offices.

In mid-March, the Bill & Melinda Gates Medical Research Institute announced it had begun the third and final phase of clinical trials for the new vaccine in seven countries. The trials should take about five years to complete. Research and production are being done in several places, including at a manufacturing facility in Hamilton owned by GSK, a giant pharmaceutical company.

Known as the forgotten pandemic, TB kills up to 1.6 million people a year, mostly in impoverished areas in Asia and Africa, despite its being both preventable and treatable. The U.S. has seen an increase in tuberculosis over the past decade, especially with the influx of migrants, and the number of cases rose by 16% from 2022 to 2023. Tuberculosis is the leading cause of death among people living with HIV, whose risk of contracting a TB infection is 20 times as great as people without HIV.

“TB is a complex pathogen that has been with human beings for ages,” said Alemnew Dagnew, who heads the program for the new vaccine for the Gates Medical Research Institute. “Because it has been with human beings for many years, it has evolved and has a mechanism to escape the immune system. And the immunology of TB is not fully understood.”

The University of Montana Center for Translational Medicine and Inimmune together have 80 employees who specialize in researching a range of adjuvants to understand the specifics of immune responses to different substances. “You have to tailor it like tools in a toolbox towards the pathogen you are vaccinating against,” Evans said. “We have a whole library of adjuvant molecules and formulations.”

Vaccines are made more precise largely by using adjuvants. There are three basic types of natural adjuvants: aluminum salts; squalene, which is made from shark liver; and some kinds of saponins, which are fat molecules. It’s not fully understood how they stimulate the immune system. The center in Missoula has also created and patented a synthetic adjuvant, UM-1098, that drives a specific type of immune response and will be added to new vaccines.

One of the most promising molecules being used to juice up the immune system response to vaccines is a saponin molecule from the bark of the quillay tree, gathered in Chile from trees at least 10 years old. Such molecules were used by Novavax in its covid vaccine and by GSK in its widely used shingles vaccine, Shingrix. These molecules are also a key component in the new tuberculosis vaccine, known as the M72 vaccine.

But there is room for improvement.

“The vaccine shows 50% efficacy, which doesn’t sound like much, but basically there is no effective vaccine currently, so 50% is better than what’s out there,” Evans said. “We’re looking to take what we learned from that vaccine development with additional adjuvants to try and make it even better and move 50% to 80% or more.”

By contrast, measles vaccines are 95% effective.

According to Medscape, around 15 vaccine candidates are being developed to replace the BCG vaccine, and three of them are in phase 3 clinical trials.

One approach Evans’ center is researching to improve the new vaccine’s efficacy is taking a piece of the bacterium that causes TB, synthesizing it, and combining it with the adjuvant QS-21, made from the quillay tree. “It stimulates the immune system in a way that is specific to TB and it drives an immune response that is even closer to what we get from natural infections,” Evans said.

The University of Montana center is researching the treatment of several problems not commonly thought of as treatable with vaccines. They are entering the first phase of clinical trials for a vaccine for allergies, for instance, and first-phase trials for a cancer vaccine. And later this year, clinical trials will begin for vaccines to block the effects of opioids like heroin and fentanyl. The University of Montana received the largest grant in its history, $33 million, for anti-opioid vaccine research. It works by creating an antibody that binds with the drug in the bloodstream, which keeps it from entering the brain and creating the high.

For now, though, the eyes of health care experts around the world are on the trials for the new TB vaccines, which, if they are successful, could help save countless lives in the world’s poorest places.

KFF Health News is a national newsroom that produces in-depth journalism about health issues and is one of the core operating programs at KFF—an independent source of health policy research, polling, and journalism. Learn more about KFF.

Subscribe to KFF Health News’ free Morning Briefing.

Share This Post

Related Posts

-

What causes food cravings? And what can we do about them?

10almonds is reader-supported. We may, at no cost to you, receive a portion of sales if you purchase a product through a link in this article.

Many of us try to eat more fruits and vegetables and less ultra-processed food. But why is sticking to your goals so hard?

High-fat, sugar-rich and salty foods are simply so enjoyable to eat. And it’s not just you – we’ve evolved that way. These foods activate the brain’s reward system because in the past they were rare.

Now, they’re all around us. In wealthy modern societies we are bombarded by advertising which intentionally reminds us about the sight, smell and taste of calorie-dense foods. And in response to these powerful cues, our brains respond just as they’re designed to, triggering an intense urge to eat them.

Here’s how food cravings work and what you can do if you find yourself hunting for sweet or salty foods.

Fascinadora/Shutterstock What causes cravings?

A food craving is an intense desire or urge to eat something, often focused on a particular food.

We are programmed to learn how good a food tastes and smells and where we can find it again, especially if it’s high in fat, sugar or salt.

Something that reminds us of enjoying a certain food, such as an eye-catching ad or delicious smell, can cause us to crave it.

Our brains learn to crave foods based on what we’ve enjoyed before. fon thachakul/Shutterstock The cue triggers a physical response, increasing saliva production and gastric activity. These responses are relatively automatic and difficult to control.

What else influences our choices?

While the effect of cues on our physical response is relatively automatic, what we do next is influenced by complex factors.

Whether or not you eat the food might depend on things like cost, whether it’s easily available, and if eating it would align with your health goals.But it’s usually hard to keep healthy eating in mind. This is because we tend to prioritise a more immediate reward, like the pleasure of eating, over one that’s delayed or abstract – including health goals that will make us feel good in the long term.

Stress can also make us eat more. When hungry, we choose larger portions, underestimate calories and find eating more rewarding.

Looking for something salty or sweet

So what if a cue prompts us to look for a certain food, but it’s not available?

Previous research suggested you would then look for anything that makes you feel good. So if you saw someone eating a doughnut but there were none around, you might eat chips or even drink alcohol.

But our new research has confirmed something you probably knew: it’s more specific than that.

If an ad for chips makes you look for food, it’s likely a slice of cake won’t cut it – you’ll be looking for something salty. Cues in our environment don’t just make us crave food generally, they prompt us to look for certain food “categories”, such as salty, sweet or creamy.

Food cues and mindless eating

Your eating history and genetics can also make it harder to suppress food cravings. But don’t beat yourself up – relying on willpower alone is hard for almost everyone.

Food cues are so powerful they can prompt us to seek out a certain food, even if we’re not overcome by a particularly strong urge to eat it. The effect is more intense if the food is easily available.

This helps explain why we can eat an entire large bag of chips that’s in front of us, even though our pleasure decreases as we eat. Sometimes we use finishing the packet as the signal to stop eating rather than hunger or desire.

Is there anything I can do to resist cravings?

We largely don’t have control over cues in our environment and the cravings they trigger. But there are some ways you can try and control the situations you make food choices in.

- Acknowledge your craving and think about a healthier way to satisfy it. For example, if you’re craving chips, could you have lightly-salted nuts instead? If you want something sweet, you could try fruit.

- Avoid shopping when you’re hungry, and make a list beforehand. Making the most of supermarket “click and collect” or delivery options can also help avoid ads and impulse buys in the aisle.

- At home, have fruit and vegetables easily available – and easy to see. Also have other nutrient dense, fibre-rich and unprocessed foods on hand such as nuts or plain yoghurt. If you can, remove high-fat, sugar-rich and salty foods from your environment.

- Make sure your goals for eating are SMART. This means they are specific, measurable, achievable, relevant and time-bound.

- Be kind to yourself. Don’t beat yourself up if you eat something that doesn’t meet your health goals. Just keep on trying.

Gabrielle Weidemann, Associate Professor in Psychological Science, Western Sydney University and Justin Mahlberg, Research Fellow, Pyschology, Monash University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Don’t Forget…

Did you arrive here from our newsletter? Don’t forget to return to the email to continue learning!

Learn to Age Gracefully

Join the 98k+ American women taking control of their health & aging with our 100% free (and fun!) daily emails:

-

It’s Not A Bloody Trend – by Kat Brown

10almonds is reader-supported. We may, at no cost to you, receive a portion of sales if you purchase a product through a link in this article.

This one’s not a clinical book, and the author is not a clinician. However, it’s not just a personal account, either. Kat Brown is an award-winning journalist (with ADHD) and has approached this journalistically.

Not just in terms of investigative journalism, either. Rather, also with her knowledge and understanding of the industry, doing for us some meta-journalism and explaining why the press have gone for many misleading headlines.

Which in this case means for example it’s not newsworthy to say that people have gone undiagnosed and untreated for years and that many continue to go unseen; we know this also about such things as endometriosis, adenomyosis, and PCOS. But some more reactionary headlines will always get attention, e.g. “look at these malingering attention-seekers”.

She also digs into the common comorbidities of various conditions, the differences it makes to friendships, families, relationships, work, self-esteem, parenting, and more.

This isn’t a “how to” book, but there’s a lot of value here if a) you have ADHD, and/or b) you spend any amount of time with someone who does.

Bottom line: if you’d like to understand “what all the fuss is about” in one book, this is the one for ADHD.

Don’t Forget…

Did you arrive here from our newsletter? Don’t forget to return to the email to continue learning!

Learn to Age Gracefully

Join the 98k+ American women taking control of their health & aging with our 100% free (and fun!) daily emails:

-

Great Sex Never Gets Old – by Kimberly Cunningham – by Kimberly Cunningham

10almonds is reader-supported. We may, at no cost to you, receive a portion of sales if you purchase a product through a link in this article.

Here some readers may be thinking “after 40? But I am 70 already” or such, so be assured, there’s no upper limit on the applicability of this book’s writings. The number of 40 was chosen more as the start point of things, because it is an age after which the majority of hormonal declines happen (and with them, often, sex drive and/or physical ability). But, as she explains, this is by no means necessarily an end, and can instead be an exciting new beginning.

She kicks things off with a “wellness check”, before diving into the science of the menopause—and yes, the andropause too.

She doesn’t stop there though, and discusses other hormones besides the obvious ones, and other non-hormonal factors that can affect sex in what for most people is the later half of life.

Nurse Cunningham, much like most of modern science, is strongly pro-HRT, and/but doesn’t claim it to be a magic bullet (though honestly, it can feel like it is! But here we’re reviewing the book, not HRT, so let’s continue), or else this book could have been a leaflet. Instead, she talks about the side-effects to expect (mostly good or neutral, but still, things you don’t want to be taken by surprise by), and what things will just be “a little different” now if you’re running on exogenous bioidentical hormones rather than ones your own body made. A lot of this comes down to how and when one takes them, by the way, since this can be different to your body making its own natural peaks and troughs.

But it’s not all about hormones; there are also plenty of chapters on social and psychological issues, as well as medical issues other than hormones.

The style is very light and conversational, while also casually dropping about 30 pages of scientific references. Like many nurses, the author knows at least as much as doctors when it comes to her area of expertise, and it shows.

Bottom line: if your sex has ever hit a slump, and/or you simply recognize that it could, this book could make a very important difference.

Click here to check out Great Sex Never Gets Old, and enjoy the best of life in the bedroom too!

Don’t Forget…

Did you arrive here from our newsletter? Don’t forget to return to the email to continue learning!

Learn to Age Gracefully

Join the 98k+ American women taking control of their health & aging with our 100% free (and fun!) daily emails: