South Indian-Style Chickpea & Mango Salad

10almonds is reader-supported. We may, at no cost to you, receive a portion of sales if you purchase a product through a link in this article.

We have a double-dose of chickpeas today, but with all the other ingredients, this dish is anything but boring. Fun fact about chickpeas though: they’re rich in sitosterol, a plant sterol that, true to its name, sits on cholesterol absorption sites, reducing the amount of dietary cholesterol absorbed. If you are vegan, this will make no difference to you because your diet does not contain cholesterol, but for everyone else, this is a nice extra bonus!

You will need

- 1 can white chickpeas, drained and rinsed

- 1 can black chickpeas (kala chana), drained and rinsed

- 9 oz fresh mango, diced (or canned is fine if that’s what’s available)

- 1½ oz ginger, peeled and grated

- 2 green chilis, finely chopped (adjust per heat preferences)

- 2 tbsp desiccated coconut (or 3 oz grated coconut, if you have it fresh)

- 8 curry leaves (dried is fine if that’s what’s available)

- 1 tsp mustard seeds

- 1 tsp cumin seeds

- 1 tsp black pepper, coarse ground

- ½ tsp MSG or 1 tsp low-sodium salt

- Juice of 1 lime

- Extra virgin olive oil

Method

(we suggest you read everything at least once before doing anything)

1) Heat some oil in a skillet over a medium heat. When it’s hot but not smoking, add the ginger, chilis, curry leaves, mustard seeds, and cumin seeds, stirring well to combine, keep going until the mustard seeds start popping.

2) Add the chickpeas (both kinds), as well as the black pepper and the MSG/salt. Once they’re warm through, take it off the heat.

3) Add the mango, coconut, and lime juice, mixing thoroughly.

4) Serve warm, at room temperature, or cold:

Enjoy!

Want to learn more?

For those interested in some of the science of what we have going on today:

- What Matters Most For Your Heart?

- Can Saturated Fats Be Healthy?

- Our Top 5 Spices: How Much Is Enough For Benefits?

Take care!

Don’t Forget…

Did you arrive here from our newsletter? Don’t forget to return to the email to continue learning!

Recommended

Learn to Age Gracefully

Join the 98k+ American women taking control of their health & aging with our 100% free (and fun!) daily emails:

-

Chaga Mushrooms’ Immune & Anticancer Potential

10almonds is reader-supported. We may, at no cost to you, receive a portion of sales if you purchase a product through a link in this article.

What Do Chaga Mushrooms Do?

Chaga mushrooms, which also go by other delightful names including “sterile conk trunk rot” and “black mass”, are a type of fungus that grow on birch trees in cold climates such as Alaska, Northern Canada, Northern Europe, and Siberia.

They’ve enjoyed a long use as a folk remedy in Northern Europe and Siberia, mostly to boost immunity, mostly in the form of a herbal tea.

Let’s see what the science says…

Does it boost the immune system?

It definitely does if you’re a mouse! We couldn’t find any studies on humans yet. But for example:

- Immunomodulatory Activity of the Water Extract from Medicinal Mushroom Inonotus obliquus

- Inonotus obliquus extracts suppress antigen-specific IgE production through the modulation of Th1/Th2 cytokines in ovalbumin-sensitized mice

(cytokines are special proteins that regulate the immune system, and Chaga tells them to tell the body to produce more white blood cells)

Wait, does that mean it increases inflammation?

Definitely not if you’re a mouse! We couldn’t find any studies on humans yet. But for example:

- Anti-inflammatory effects of orally administered Inonotus obliquus in ulcerative colitis

- Orally administered aqueous extract of Inonotus obliquus ameliorates acute inflammation

Anti-inflammatory things often fight cancer. Does chaga?

Definitely if you’re a mouse! We couldn’t find any studies in human cancer patients yet. But for example:

While in vivo human studies are conspicuous by their absence, there have been in vitro human studies, i.e., studies performed on cancerous human cell samples in petri dishes. They are promising:

- Anticancer activities of extracts and compounds from the mushroom Inonotus obliquus

- Extract of Innotus obliquus induces G1 cell cycle arrest in human colon cancer cells

- Anticancer activity of Inonotus obliquus extract in human cancer cells

I heard it fights diabetes; does it?

You’ll never see this coming, but: definitely if you’re a mouse! We couldn’t find any human studies yet. But for example:

- Anti-diabetic effects of Inonotus obliquus in type 2 diabetic mice

- Anti-diabetic effects of Inonotus obliquus in type 2 diabetic mice and potential mechanism

Is it safe?

Honestly, there simply have been no human safety studies to know for sure, or even to establish an appropriate dosage.

Its only-partly-understood effects on blood sugar levels and the immune system may make it more complicated for people with diabetes and/or autoimmune disorders, and such people should definitely seek medical advice before taking chaga.

Additionally, chaga contains a protein that can prevent blood clotting. That might be great by default if you are at risk of blood clots, but not so great if you are already on blood-thinning medication, or otherwise have a bleeding disorder, or are going to have surgery soon.

As with anything, we’re not doctors, let alone your doctors, so please consult yours before trying chaga.

Where can we get it?

We don’t sell it (or anything else), but for your convenience, here’s an example product on Amazon.

Enjoy!

Share This Post

-

AI: The Doctor That Never Tires?

10almonds is reader-supported. We may, at no cost to you, receive a portion of sales if you purchase a product through a link in this article.

AI: The Doctor That Never Tires?

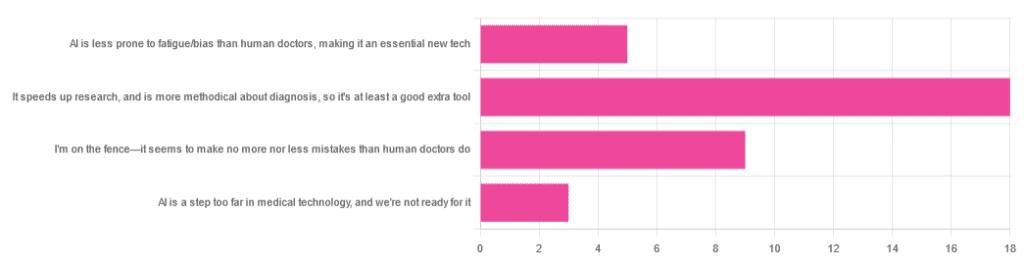

We asked you for your opinion on the use of Artificial Intelligence (AI) in healthcare, and got the above-depicted, below-described set of results:

- A little over half of respondents to the poll voted for “It speeds up research, and is more methodical about diagnosis, so it’s at least a good extra tool”

- A quarter of respondents voted for “I’m on the fence—it seems to make no more nor less mistakes than human doctors do”

- A little under a fifth of respondents voted for “AI is less prone to fatigue/bias than human doctors, making it an essential new tech”

- Three respondents voted for “AI is a step too far in medical technology, and we’re not ready for it”

Writer’s note: I’m a professional writer (you’d never have guessed, right?) and, apparently, I really did write “no more nor less mistakes”, despite the correct grammar being “no more nor fewer mistakes”. Now, I know this, and in fact, people getting less/fewer wrong is a pet hate of mine. Nevertheless, I erred.

Yet, now that I’m writing this out in my usual software, and not directly into the poll-generation software, my (AI!) grammar/style-checker is highlighting the error for me.

Now, an AI could not do my job. ChatGPT would try, and fail miserably. But can technology help me do mine better? Absolutely!

And still, I dismiss a lot of the AI’s suggestions, because I know my field and can make informed choices. I don’t follow it blindly, and I think that’s key.

AI is less prone to fatigue/bias than human doctors, making it an essential new tech: True or False?

True—with one caveat.

First, a quick anecdote from a subscriber who selected this option in the poll:

❝As long as it receives the same data inputs as my doctor (ie my entire medical history), I can see it providing a much more personalised service than my human doctor who is always forgetting what I have told him. I’m also concerned that my doctor may be depressed – not an ailment that ought to affect AI! I recently asked my newly qualified doctor goddaughter whether she would prefer to be treated by a human or AI doctor. No contest, she said – she’d go with AI. Her argument was that human doctors leap to conclusions, rather than properly weighing all the evidence – meaning AI, as long as it receives the same inputs, will be much more reliable❞

Now, an anecdote is not data, so what does the science say?

Well… It says the same:

❝Of 6695 responding physicians in active practice, 6586 provided information on the areas of interest: 3574 (54.3%) reported symptoms of burnout, 2163 (32.8%) reported excessive fatigue, and 427 (6.5%) reported recent suicidal ideation, with 255 of 6563 (3.9%) reporting a poor or failing patient safety grade in their primary work area and 691 of 6586 (10.5%) reporting a major medical error in the prior 3 months. Physicians reporting errors were more likely to have symptoms of burnout (77.6% vs 51.5%; P<.001), fatigue (46.6% vs 31.2%; P<.001), and recent suicidal ideation (12.7% vs 5.8%; P<.001).❞

See the damning report for yourself: Physician Burnout, Well-being, and Work Unit Safety Grades in Relationship to Reported Medical Errors

AI, of course, does not suffer from burnout, fatigue, or suicidal ideation.

So, what was the caveat?

The caveat is about bias. Humans are biased, and that goes for medical practitioners just the same. AI’s machine learning is based on source data, and the source data comes from humans, who are biased.

See: Bias and Discrimination in AI: A Cross-Disciplinary Perspective

So, AI can perpetuate human biases and doesn’t have a special extra strength in this regard.

The lack of burnout, fatigue, and suicidal ideation, however, make a big difference.

AI speeds up research, and is more methodical about diagnosis: True or False?

True! AI is getting more and more efficient at this, and as has been pointed out, doesn’t make errors due to fatigue, and often comes to accurate conclusions near-instantaneously. To give just one example:

❝Deep learning algorithms achieved better diagnostic performance than a panel of 11 pathologists participating in a simulation exercise designed to mimic routine pathology workflow; algorithm performance was comparable with an expert pathologist interpreting whole-slide images without time constraints. The area under the curve was 0.994 (best algorithm) vs 0.884 (best pathologist).❞

About that “getting more and more efficient at this”; it’s in the nature of machine learning that every new piece of data improves the neural net being used. So long as it is getting fed new data, which it can process at rate far exceeding humans’ abilities, it will always be constantly improving.

AI makes no more nor

lessfewer mistakes than humans do: True or False?False! AI makes fewer, now. This study is from 2021, and it’s only improved since then:

❝Professionals only came to the same conclusions [as each other] approximately 75 per cent of the time. More importantly, machine learning produced fewer decision-making errors than did all the professionals❞

See: AI can make better clinical decisions than humans: study

All that said, we’re not quite at Star Trek levels of “AI can do a human’s job entirely” just yet:

BMJ | Artificial intelligence versus clinicians: pros and cons

To summarize: medical AI is a powerful tool that:

- Makes healthcare more accessible

- Speeds up diagnosis

- Reduces human error

…and yet, for now at least, still requires human oversights, checks and balances.

Essentially: it’s not really about humans vs machines at all. It’s about humans and machines giving each other information, and catching any mistakes made by the other. That way, humans can make more informed decisions, and still keep a “hand on the wheel”.

Share This Post

-

When You “Should” Be In Better Shape

10almonds is reader-supported. We may, at no cost to you, receive a portion of sales if you purchase a product through a link in this article.

It’s easy to think that we “should” be many things that we aren’t. However, it can be counterproductive to implementing real change:

The problem with “should”

The word “should” often sabotages changes in mindset and habit formation. Saying things like “I should be further along” typically leads to frustration, feelings of failure, and ultimately a lack of motivation to take action. Yes, in the first instance, “I should…” can be a motivator, but when your goals are not achieved by the second session, and the “I should…” is still there, the subconscious says “well, clearly this is not working”. Even though the conscious mind can easily see the fallacy in that dysfunctional line of thinking, the subconscious is easily swayed by such things, and in turn easily sways our actual behaviors.

Also, even before that, if goals feel impossible, people often do nothing instead of making small, manageable changes.

So, what should we do instead?

Step 1: assess your current lifestyle and priorities. Your current results are a reflection of past habits and actions, including dieting practices, inconsistent workouts, and lack of planning. Instead of searching for a “perfect plan,” first acknowledge your current lifestyle and priorities. Then, identify which habits are beneficial, which ones hold you back, and what common excuses you make. By understanding where you are now, you can create a sustainable plan that fits your life rather than fighting against it.

Step 2: define your future lifestyle. It’s not enough to just set goals—you need to define what the lifestyle associated with those goals looks like. Recognize that real change requires adjustments in habits and routines. Don’t stress over whether these changes feel overwhelming; simply identify what might be necessary. Writing things down (and then consulting them often, not just putting them away never to be seen again) makes them more tangible and helps create a roadmap for progress.

Step 3: make one small change today. Rather than making vague or overwhelming changes, start with one small, realistic step that aligns with your goals. Building momentum through cumulatively beneficial small actions leads to longer-lasting motivation. Also, instead of focusing on what you need to cut out, look for positive habits to add, as this makes change easier. Track your progress visibly—like using a checklist—and commit to revisiting and adding new changes weekly.

For more on all of this, enjoy:

Click Here If The Embedded Video Doesn’t Load Automatically!

Want to learn more?

You might also like:

How To Plan For The Unplannable And Always Follow Through

Take care!

Share This Post

Related Posts

-

Osteoporosis & Exercises: Which To Do (And Which To Avoid)

10almonds is reader-supported. We may, at no cost to you, receive a portion of sales if you purchase a product through a link in this article.

It’s Q&A Day at 10almonds!

Have a question or a request? You can always hit “reply” to any of our emails, or use the feedback widget at the bottom!

In cases where we’ve already covered something, we might link to what we wrote before, but will always be happy to revisit any of our topics again in the future too—there’s always more to say!

As ever: if the question/request can be answered briefly, we’ll do it here in our Q&A Thursday edition. If not, we’ll make a main feature of it shortly afterwards!

So, no question/request too big or small

❝Any idea about the latest research on the most effective exercises for osteoporosis?❞

While there isn’t much new of late in this regard, there is plenty of research!

First, what you might want to avoid:

- Sit-ups, and other exercises with a lot of repeated spinal flexion

- Running, and other high-impact exercises

- Skiing, horse-riding, and other activities with a high risk of falling

- Golf and tennis (both disproportionately likely to result in injuries to wrists, elbows, and knees)

Next, what you might want to bear in mind:

While in principle resistance training is good for building strong bones, good form becomes all the more important if you have osteoporosis, so consider working with a trainer if you’re not 100% certain you know what you’re doing:

Some of the best exercises for osteoporosis are isometric exercises:

5 Isometric Exercises for Osteoporosis (with textual explanations and illustrative GIFs)

You might also like this bone-strengthening exercise routine from corrective exercise specialist Kendra Fitzgerald:

Enjoy!

Don’t Forget…

Did you arrive here from our newsletter? Don’t forget to return to the email to continue learning!

Learn to Age Gracefully

Join the 98k+ American women taking control of their health & aging with our 100% free (and fun!) daily emails:

-

What happens when I stop taking a drug like Ozempic or Mounjaro?

10almonds is reader-supported. We may, at no cost to you, receive a portion of sales if you purchase a product through a link in this article.

Hundreds of thousands of people worldwide are taking drugs like Ozempic to lose weight. But what do we actually know about them? This month, The Conversation’s experts explore their rise, impact and potential consequences.

Drugs like Ozempic are very effective at helping most people who take them lose weight. Semaglutide (sold as Wegovy and Ozempic) and tirzepatide (sold as Zepbound and Mounjaro) are the most well known in the class of drugs that mimic hormones to reduce feelings of hunger.

But does weight come back when you stop using it?

The short answer is yes. Stopping tirzepatide and semaglutide will result in weight regain in most people.

So are these medications simply another (expensive) form of yo-yo dieting? Let’s look at what the evidence shows so far.

It’s a long-term treatment, not a short course

If you have a bacterial infection, antibiotics will help your body fight off the germs causing your illness. You take the full course of medication, and the infection is gone.

For obesity, taking tirzepatide or semaglutide can help your body get rid of fat. However it doesn’t fix the reasons you gained weight in the first place because obesity is a chronic, complex condition. When you stop the medications, the weight returns.

Perhaps a more useful comparison is with high blood pressure, also known as hypertension. Treatment for hypertension is lifelong. It’s the same with obesity. Medications work, but only while you are taking them. (Though obesity is more complicated than hypertension, as many different factors both cause and perpetuate it.)

Obesity drugs only work while you’re taking them. KK Stock/Shutterstock Therefore, several concurrent approaches are needed; taking medication can be an important part of effective management but on its own, it’s often insufficient. And in an unwanted knock-on effect, stopping medication can undermine other strategies to lose weight, like eating less.

Why do people stop?

Research trials show anywhere from 6% to 13.5% of participants stop taking these drugs, primarily because of side effects.

But these studies don’t account for those forced to stop because of cost or widespread supply issues. We don’t know how many people have needed to stop this medication over the past few years for these reasons.

Understanding what stopping does to the body is therefore important.

So what happens when you stop?

When you stop using tirzepatide or semaglutide, it takes several days (or even a couple of weeks) to move out of your system. As it does, a number of things happen:

- you start feeling hungry again, because both your brain and your gut no longer have the medication working to make you feel full

When you stop taking it, you feel hungry again. Stock-Asso/Shutterstock - blood sugars increase, because the medication is no longer acting on the pancreas to help control this. If you have diabetes as well as obesity you may need to take other medications to keep these in an acceptable range. Whether you have diabetes or not, you may need to eat foods with a low glycemic index to stabilise your blood sugars

- over the longer term, most people experience a return to their previous blood pressure and cholesterol levels, as the weight comes back

- weight regain will mostly be in the form of fat, because it will be gained faster than skeletal muscle.

While you were on the medication, you will have lost proportionally less skeletal muscle than fat, muscle loss is inevitable when you lose weight, no matter whether you use medications or not. The problem is, when you stop the medication, your body preferentially puts on fat.

Is stopping and starting the medications a problem?

People whose weight fluctuates with tirzepatide or semaglutide may experience some of the downsides of yo-yo dieting.

When you keep going on and off diets, it’s like a rollercoaster ride for your body. Each time you regain weight, your body has to deal with spikes in blood pressure, heart rate, and how your body handles sugars and fats. This can stress your heart and overall cardiovascular system, as it has to respond to greater fluctuations than usual.

Interestingly, the risk to the body from weight fluctuations is greater for people who are not obese. This should be a caution to those who are not obese but still using tirzepatide or semaglutide to try to lose unwanted weight.

How can you avoid gaining weight when you stop?

Fear of regaining weight when stopping these medications is valid, and needs to be addressed directly. As obesity has many causes and perpetuating factors, many evidence-based approaches are needed to reduce weight regain. This might include:

- getting quality sleep

- exercising in a way that builds and maintains muscle. While on the medication, you will likely have lost muscle as well as fat, although this is not inevitable, especially if you exercise regularly while taking it

Prioritise building and maintaining muscle. EvMedvedeva/Shutterstock - addressing emotional and cultural aspects of life that contribute to over-eating and/or eating unhealthy foods, and how you view your body. Stigma and shame around body shape and size is not cured by taking this medication. Even if you have a healthy relationship with food, we live in a culture that is fat-phobic and discriminates against people in larger bodies

- eating in a healthy way, hopefully continuing with habits that were formed while on the medication. Eating meals that have high nutrition and fibre, for example, and lower overall portion sizes.

Many people will stop taking tirzepatide or semaglutide at some point, given it is expensive and in short supply. When you do, it is important to understand what will happen and what you can do to help avoid the consequences. Regular reviews with your GP are also important.

Read the other articles in The Conversation’s Ozempic series here.

Natasha Yates, General Practitioner, PhD Candidate, Bond University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Don’t Forget…

Did you arrive here from our newsletter? Don’t forget to return to the email to continue learning!

Learn to Age Gracefully

Join the 98k+ American women taking control of their health & aging with our 100% free (and fun!) daily emails:

-

Qigong: A Breath Of Fresh Air?

10almonds is reader-supported. We may, at no cost to you, receive a portion of sales if you purchase a product through a link in this article.

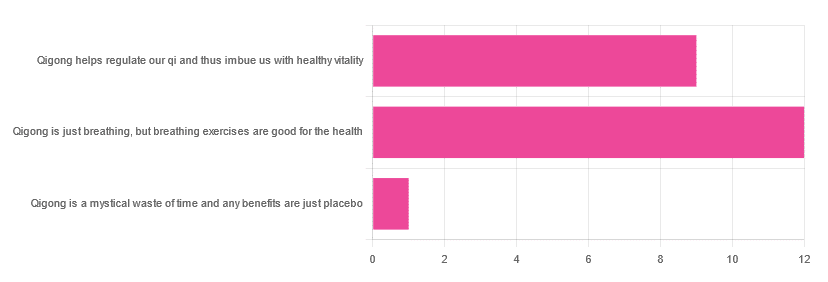

Qigong: Breathing Is Good (Magic Remains Unverified)

In Tuesday’s newsletter, we asked you for your opinions of qigong, and got the above-depicted, below-described, set of responses:

- About 55% said “Qigong is just breathing, but breathing exercises are good for the health”

- About 41% said “Qigong helps regulate our qi and thus imbue us with healthy vitality”

- One (1) person said “Qigong is a mystical waste of time and any benefits are just placebo”

The sample size was a little low for this one, but the results were quite clearly favorable, one way or another.

So what does the science say?

Qigong is just breathing: True or False?

True or False, depending on how we want to define it—because qigong ranges in its presentation from indeed “just breathing exercises”, to “breathing exercises with visualization” to “special breathing exercises with visualization that have to be exactly this way, with these hand and sometimes body movements also, which also must be just right”, to far more complex definitions that involve qi by various mystical definitions, and/or an appeal to a scientific analog of qi; often some kind of bioelectrical field or such.

There is, it must be said, no good quality evidence for the existence of qi.

Writer’s note, lest 41% of you want my head now: I’ve been practicing qigong and related arts for about 30 years and find such to be of great merit. This personal experience and understanding does not, however, change the state of affairs when it comes to the availability (or rather, the lack) of high quality clinical evidence to point to.

Which is not to say there is no clinical evidence, for example:

Acute Physiological and Psychological Effects of Qigong Exercise in Older Practitioners

…found that qigong indeed increased meridian electrical conductance!

Except… Electrical conductance is measured with galvanic skin responses, which increase with sweat. But don’t worry, to control for that, they asked participants to dry themselves with a towel. Unfortunately, this overlooks the fact that a) more sweat can come where that came from, because the body will continue until it is satisfied of adequate homeostasis, and b) drying oneself with a towel will remove the moisture better than it’ll remove the salts from the skin—bearing in mind that it’s mostly the salts, rather than the moisture itself, that improve the conductivity (pure distilled water does conduct electricity, but not very well).

In other words, this was shoddy methodology. How did it pass peer review? Well, here’s an insight into that journal’s peer review process…

❝The peer-review system of EBCAM is farcical: potential authors who send their submissions to EBCAM are invited to suggest their preferred reviewers who subsequently are almost invariably appointed to do the job. It goes without saying that such a system is prone to all sorts of serious failures; in fact, this is not peer-review at all, in my opinion, it is an unethical sham.❞

~ Dr. Edzard Ernst, a founding editor of EBCAM (he since left, and decries what has happened to it since)

One of the other key problems is: how does one test qigong against placebo?

Scientists have looked into this question, and their answers have thus far been unsatisfying, and generally to the tune of the true-but-unhelpful statement that “future research needs to be better”:

Problems of scientific methodology related to placebo control in Qigong studies: A systematic review

Most studies into qigong are interventional studies, that is to say, they measure people’s metrics (for example, blood pressure, heart rate, maybe immune function biomarkers, sleep quality metrics of various kinds, subjective reports of stress levels, physical biomarkers of stress levels, things like that), then do a course of qigong (perhaps 6 weeks, for example), then measure them again, and see if the course of qigong improved things.

This almost always results in an improvement when looking at the before-and-after, but it says nothing for whether the benefits were purely placebo.

We did find one study that claimed to be placebo-controlled:

…but upon reading the paper itself carefully, it turned out that while the experimental group did qigong, the control group did a reading exercise. Which is… Saying how well qigong performs vs reading (qigong did outperform reading, for the record), but nothing for how well it performs vs placebo, because reading isn’t a remotely credible placebo.

See also: Placebo Effect: Making Things Work Since… Well, A Very Long Time Ago ← this one explains a lot about how placebo effect does work

Qigong is a mystical waste of time: True or False?

False! This one we can answer easily. Interventional studies invariably find it does help, and the fact remains that even if placebo is its primary mechanism of action, it is of benefit and therefore not a waste of time.

Which is not to say that placebo is its only, or even necessarily primary, mechanism of action.

Even from a purely empirical evidence-based medicine point of view, qigong is at the very least breathing exercises plus (usually) some low-impact body movement. Those are already two things that can be looked at, mechanistic processes pointed to, and declarations confidently made of “this is an activity that’s beneficial for health”.

See for example:

- Effects of Qigong practice in office workers with chronic non-specific low back pain: A randomized control trial

- Qigong for the Prevention, Treatment, and Rehabilitation of COVID-19 Infection in Older Adults

- Impact of Medical Qigong on quality of life, fatigue, mood and inflammation in cancer patients: a randomized controlled trial

…and those are all from respectable journals with meaningful peer review processes.

None of them are placebo-controlled, because there is no real option of “and group B will only be tricked into believing they are doing deep breathing exercises with low-impact movements”; that’s impossible.

But! They each show how doing qigong reliably outperforms not doing qigong for various measurable metrics of health.

And, we chose examples with physical symptoms and where possible empirically measurable outcomes (such as COVID-19 infection levels, or inflammatory responses); there are reams of studies showings qigong improves purely subjective wellbeing—but the latter could probably be claimed for any enjoyable activity, whereas changes in inflammatory biomarkers, not such much.

In short: for most people, it indeed reliably helps with many things. And importantly, it has no particular risks associated with it, and it’s almost universally framed as a complementary therapy rather than an alternative therapy.

This is critical, because it means that whereas someone may hold off on taking evidence-based medicines while trying out (for example) homeopathy, few people are likely to hold off on other treatments while trying out qigong—since it’s being viewed as a helper rather than a Hail-Mary.

Want to read more about qigong?

Here’s the NIH’s National Center for Complementary and Integrative Health has to say. It cites a lot of poor quality science, but it does mention when the science it’s citing is of poor quality, and over all gives quite a rounded view:

Enjoy!

Don’t Forget…

Did you arrive here from our newsletter? Don’t forget to return to the email to continue learning!

Learn to Age Gracefully

Join the 98k+ American women taking control of their health & aging with our 100% free (and fun!) daily emails: