Qigong: A Breath Of Fresh Air?

10almonds is reader-supported. We may, at no cost to you, receive a portion of sales if you purchase a product through a link in this article.

Qigong: Breathing Is Good (Magic Remains Unverified)

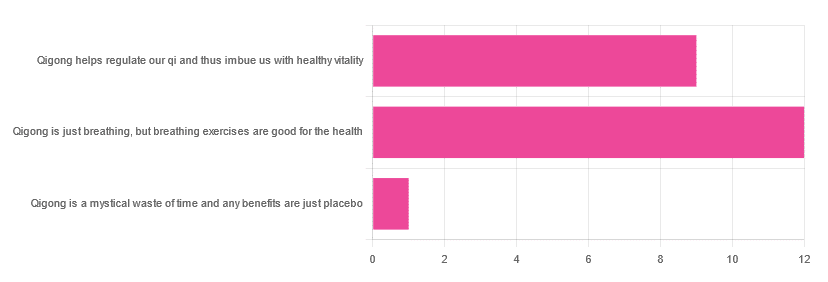

In Tuesday’s newsletter, we asked you for your opinions of qigong, and got the above-depicted, below-described, set of responses:

- About 55% said “Qigong is just breathing, but breathing exercises are good for the health”

- About 41% said “Qigong helps regulate our qi and thus imbue us with healthy vitality”

- One (1) person said “Qigong is a mystical waste of time and any benefits are just placebo”

The sample size was a little low for this one, but the results were quite clearly favorable, one way or another.

So what does the science say?

Qigong is just breathing: True or False?

True or False, depending on how we want to define it—because qigong ranges in its presentation from indeed “just breathing exercises”, to “breathing exercises with visualization” to “special breathing exercises with visualization that have to be exactly this way, with these hand and sometimes body movements also, which also must be just right”, to far more complex definitions that involve qi by various mystical definitions, and/or an appeal to a scientific analog of qi; often some kind of bioelectrical field or such.

There is, it must be said, no good quality evidence for the existence of qi.

Writer’s note, lest 41% of you want my head now: I’ve been practicing qigong and related arts for about 30 years and find such to be of great merit. This personal experience and understanding does not, however, change the state of affairs when it comes to the availability (or rather, the lack) of high quality clinical evidence to point to.

Which is not to say there is no clinical evidence, for example:

Acute Physiological and Psychological Effects of Qigong Exercise in Older Practitioners

…found that qigong indeed increased meridian electrical conductance!

Except… Electrical conductance is measured with galvanic skin responses, which increase with sweat. But don’t worry, to control for that, they asked participants to dry themselves with a towel. Unfortunately, this overlooks the fact that a) more sweat can come where that came from, because the body will continue until it is satisfied of adequate homeostasis, and b) drying oneself with a towel will remove the moisture better than it’ll remove the salts from the skin—bearing in mind that it’s mostly the salts, rather than the moisture itself, that improve the conductivity (pure distilled water does conduct electricity, but not very well).

In other words, this was shoddy methodology. How did it pass peer review? Well, here’s an insight into that journal’s peer review process…

❝The peer-review system of EBCAM is farcical: potential authors who send their submissions to EBCAM are invited to suggest their preferred reviewers who subsequently are almost invariably appointed to do the job. It goes without saying that such a system is prone to all sorts of serious failures; in fact, this is not peer-review at all, in my opinion, it is an unethical sham.❞

~ Dr. Edzard Ernst, a founding editor of EBCAM (he since left, and decries what has happened to it since)

One of the other key problems is: how does one test qigong against placebo?

Scientists have looked into this question, and their answers have thus far been unsatisfying, and generally to the tune of the true-but-unhelpful statement that “future research needs to be better”:

Problems of scientific methodology related to placebo control in Qigong studies: A systematic review

Most studies into qigong are interventional studies, that is to say, they measure people’s metrics (for example, blood pressure, heart rate, maybe immune function biomarkers, sleep quality metrics of various kinds, subjective reports of stress levels, physical biomarkers of stress levels, things like that), then do a course of qigong (perhaps 6 weeks, for example), then measure them again, and see if the course of qigong improved things.

This almost always results in an improvement when looking at the before-and-after, but it says nothing for whether the benefits were purely placebo.

We did find one study that claimed to be placebo-controlled:

…but upon reading the paper itself carefully, it turned out that while the experimental group did qigong, the control group did a reading exercise. Which is… Saying how well qigong performs vs reading (qigong did outperform reading, for the record), but nothing for how well it performs vs placebo, because reading isn’t a remotely credible placebo.

See also: Placebo Effect: Making Things Work Since… Well, A Very Long Time Ago ← this one explains a lot about how placebo effect does work

Qigong is a mystical waste of time: True or False?

False! This one we can answer easily. Interventional studies invariably find it does help, and the fact remains that even if placebo is its primary mechanism of action, it is of benefit and therefore not a waste of time.

Which is not to say that placebo is its only, or even necessarily primary, mechanism of action.

Even from a purely empirical evidence-based medicine point of view, qigong is at the very least breathing exercises plus (usually) some low-impact body movement. Those are already two things that can be looked at, mechanistic processes pointed to, and declarations confidently made of “this is an activity that’s beneficial for health”.

See for example:

- Effects of Qigong practice in office workers with chronic non-specific low back pain: A randomized control trial

- Qigong for the Prevention, Treatment, and Rehabilitation of COVID-19 Infection in Older Adults

- Impact of Medical Qigong on quality of life, fatigue, mood and inflammation in cancer patients: a randomized controlled trial

…and those are all from respectable journals with meaningful peer review processes.

None of them are placebo-controlled, because there is no real option of “and group B will only be tricked into believing they are doing deep breathing exercises with low-impact movements”; that’s impossible.

But! They each show how doing qigong reliably outperforms not doing qigong for various measurable metrics of health.

And, we chose examples with physical symptoms and where possible empirically measurable outcomes (such as COVID-19 infection levels, or inflammatory responses); there are reams of studies showings qigong improves purely subjective wellbeing—but the latter could probably be claimed for any enjoyable activity, whereas changes in inflammatory biomarkers, not such much.

In short: for most people, it indeed reliably helps with many things. And importantly, it has no particular risks associated with it, and it’s almost universally framed as a complementary therapy rather than an alternative therapy.

This is critical, because it means that whereas someone may hold off on taking evidence-based medicines while trying out (for example) homeopathy, few people are likely to hold off on other treatments while trying out qigong—since it’s being viewed as a helper rather than a Hail-Mary.

Want to read more about qigong?

Here’s the NIH’s National Center for Complementary and Integrative Health has to say. It cites a lot of poor quality science, but it does mention when the science it’s citing is of poor quality, and over all gives quite a rounded view:

Enjoy!

Don’t Forget…

Did you arrive here from our newsletter? Don’t forget to return to the email to continue learning!

Recommended

Learn to Age Gracefully

Join the 98k+ American women taking control of their health & aging with our 100% free (and fun!) daily emails:

-

Black Bean & Butternut Balti

10almonds is reader-supported. We may, at no cost to you, receive a portion of sales if you purchase a product through a link in this article.

Protein, fiber, and pungent polyphenols abound in this tasty dish that’s good for your gut, heart, brain, and more:

You will need

- 2 cans (each 14 oz or thereabouts) black beans, drained and rinsed (or: 2 cups black beans, cooked, drained, and rinsed)

- 1 butternut squash, peeled and cut into ½” cubes

- 1 cauliflower, cut into florets

- 1 red onion, finely chopped

- 1 can (14 oz or thereabouts) chopped tomatoes

- 1 cup coconut milk

- ½ bulb garlic, crushed

- 1″ piece of fresh ginger, peeled and finely chopped

- 1 fresh red chili (or multiply per your preference and the strength of your chilis), finely chopped

- 1 tbsp black pepper, coarse ground

- 1 tbsp garam masala

- 2 tsp cumin seeds

- 2 tsp ground coriander

- 1 tsp ground turmeric

- 1 tsp ground paprika

- ½ tsp MSG or 1 tsp low-sodium salt

- Juice of ½ lemon

- Extra virgin olive oil

Method

(we suggest you read everything at least once before doing anything)

1) Preheat the oven to 400℉ / 200℃.

2) Toss the squash and cauliflower in a little olive oil, to coat evenly. No need to worry about seasoning, because these are going into the curry later and will get plenty there.

3) Roast them on a baking tray lined with baking paper for about 25 minutes.

You can enjoy a 10-minute break for the first 10 minutes of that, before continuing, such that the timing will be perfect:

4) Heat a little oil in a sauté pan (or anything that’s suitable for both frying and adding volume; we’re going to be using the space later; everything is going in here!) and fry the onion on medium for about 5 minutes, stirring well.

5) Add the spices/seasonings, including the garlic, ginger, and chili, and stir well to combine.

6) Add the tomatoes, beans, and coconut milk, and simmer for 10 minutes. You can add a little water at any time if it seems to need it.

7) Stir in the roasted vegetables (they should be finished now), and heat through. Add the lemon juice and stir.

8) Serve as-is, or with your preferred carbohydrate (we recommend our Tasty Versatile Rice recipe), or if you have time, keep it warm for a while until you’re ready to use it (the flavors will benefit from this time, if available).

Enjoy!

Want to learn more?

For those interested in some of the science of what we have going on today:

- Chickpeas vs Black Beans – Which is Healthier?

- Butternut Squash vs Pumpkin – Which is Healthier?

- Our Top 5 Spices: How Much Is Enough For Benefits? ← 5/5 today!

Take care!

Share This Post

-

Vibration Plate, Review After 6 Months: Is It Worth It?

10almonds is reader-supported. We may, at no cost to you, receive a portion of sales if you purchase a product through a link in this article.

Is it push-button exercise, or an expensive fad, or something else entirely? Robin, from “The Science of Self-Care”, has insights:

Science & Experience

According to the science (studies cited in the video and linked-to in the video description, underneath it on YouTube), vibration therapy does have some clear benefits, namely:

- Bone health (helps with bone density, particularly beneficial for postmenopausal women)

- Muscle recovery (reduces lactate levels, aiding faster recovery)

- Joint health (reduces pain and improves function in osteoarthritis patients)

- Muscle stimulation (helps older adults maintain muscle mass)

- Cognitive function (due to increased blood flow to the brain)

And from her personal experience, the benefits included:

- Improved recovery after exercise, reducing muscle soreness and stiffness

- Reduced back pain and improved posture (not surprising, given the need for stabilizing muscles when using one of these)

- Better circulation and (likely resulting from same) skin clarity

She did not, however, notice:

- Any reduction in cellulite

- Any change in body composition (fat loss or muscle gain)

For a deeper look into these things and more, plus a demonstration of how the machine actually operates, enjoy:

Click Here If The Embedded Video Doesn’t Load Automatically!

Want to learn more?

You might also like to read:

Take care!

Share This Post

-

Do You Need to Wear Sunscreen Indoors? An Analysis

10almonds is reader-supported. We may, at no cost to you, receive a portion of sales if you purchase a product through a link in this article.

Dr. Michelle Wong—chemist, science educator, and cosmetician—explains the science:

Factors to take into account

UVA and UVB aren’t entirely interchangeable, so it’s important to know what you’re up against.

Sunscreen is rated by SPF, which indicates UVB protection—guarding against burning, skin cancer, and premature aging. Broad spectrum or UVA ratings measure protection against UVA rays, which cause tanning, contribute to melanoma, and can lead to skin aging and hyperpigmentation. However, most UV studies are based on white skin, which may not apply universally.

The need for sunscreen indoors depends on how much UV exposure you receive there:

- Direct exposure occurs when sunlight shines directly on you, such as when sitting by a window.

- Diffuse exposure happens when UV rays are scattered by air molecules or reflected off surfaces, which can still occur in shaded areas.

Indoors, walls and barriers do reduce UV exposure significantly. However, factors like window size, distance from windows, and the type of glass (which blocks UVB but not all UVA) play important roles in determining exposure.

The UV index (your phone’s weather app will probably have this) indicates the level of sunburn-causing UV in a specific area at a particular time. In Sydney, for example (where Dr. Wong is), the UV index can vary from 12 in summer to 2 in winter. Although UVA levels fluctuate less dramatically than UVB, they still peak during midday and in summer. Health guidelines in countries like Australia recommend wearing sunscreen when the UV index is 3 or above, but not necessarily every day.

Personal factors also influence the need for sunscreen indoors. People with darker skin, who have more melanin, may need less protection from incidental UV exposure but might still require UVA protection to prevent pigmentation. Those using skincare products that increase UV sensitivity, like alpha hydroxy acids, or those with specific medical conditions, such as photosensitivity or a family history of skin cancer, may also get particular benefit from wearing sunscreen indoors.

As to the downsides? There are some drawbacks to wearing sunscreen indoors, including cost, the effort required for application, and the risk of clogged pores. Though health concerns related to sunscreen are generally minor, they may tip the balance against wearing it if UV exposure is minimal.

For more on all of this plus visual teaching aids, enjoy:

Click Here If The Embedded Video Doesn’t Load Automatically!

Want to learn more?

You might also like:

Do We Need Sunscreen In Winter, Really? ← we tackle the science behind the answer to this similar* question

*But different, because now we need to take into account such things as axial tilt, the sun’s trajectory through the atmosphere (and thus how much gets reflected, refracted, diffused, etc—or not, as the case may be).

Take care!

Share This Post

Related Posts

-

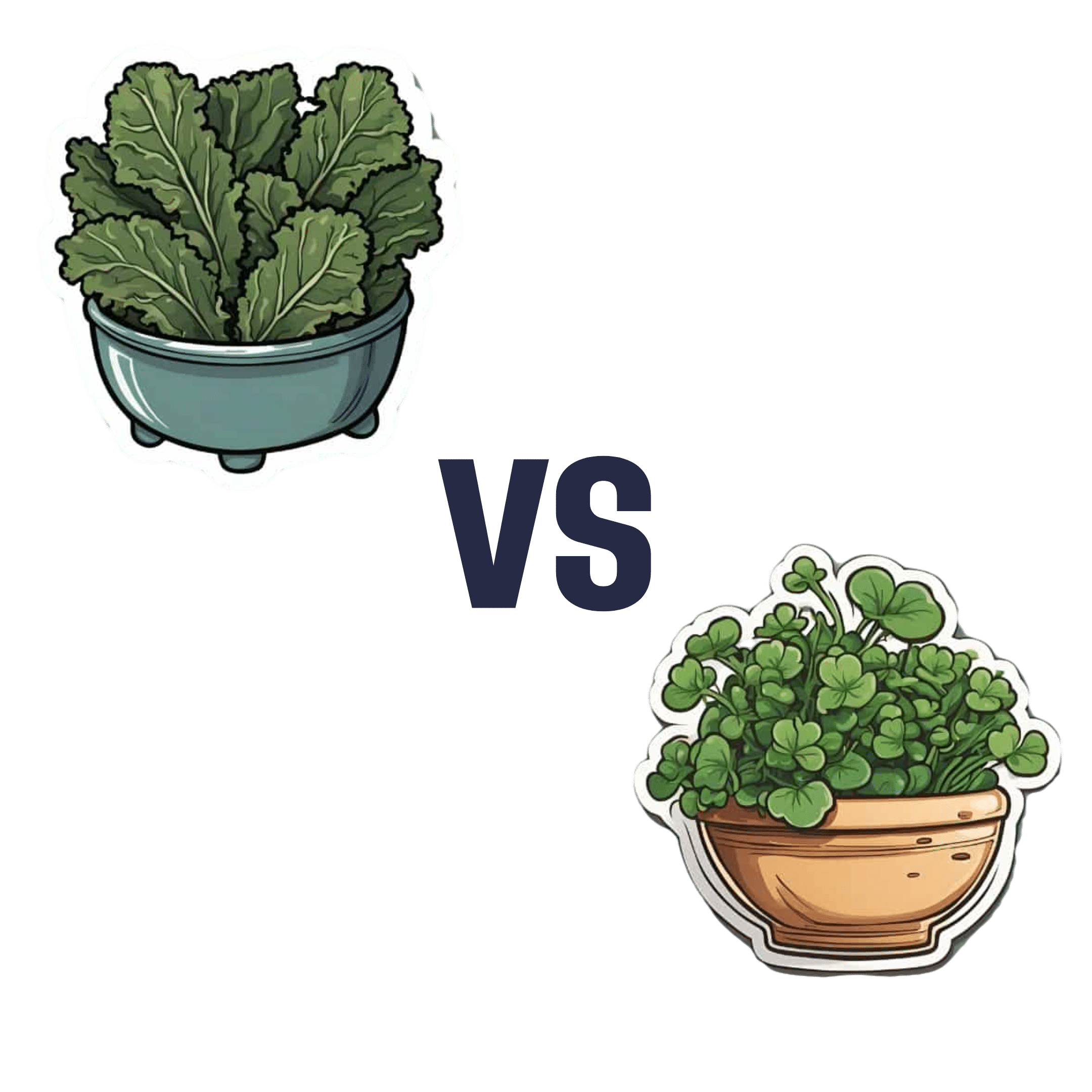

Kale vs Watercress – Which is Healthier?

10almonds is reader-supported. We may, at no cost to you, receive a portion of sales if you purchase a product through a link in this article.

Our Verdict

When comparing kale to watercress, we picked the kale.

Why?

It was very close! If ever we’ve been tempted to call something a tie, this has been the closest so far.

Their macros are close; watercress has a tiny amount more protein and slightly lower carbs, but these numbers are tiny, so it’s not really a factor. Nevertheless, on macros alone we’d call this a slight nominal win for watercress.

In terms of vitamins, they’re even. Watercress has higher vitamin E and choline (sometimes considered a vitamin), as well as being higher in some B vitamins. Kale has higher vitamins A and K, as well as being higher in some other B vitamins.

In the category of minerals, watercress has higher calcium, magnesium, phosphorus, and potassium, while kale has higher copper, iron, manganese, and zinc. The margins are slightly wider for kale’s more plentiful minerals though, so we’ll call this section a marginal win for kale.

When it comes to polyphenols, kale takes and maintains the lead here, with around 2x the quercetin and 27x the kaempferol. Watercress does have some lignans that kale doesn’t, but ultimately, kale’s strong flavonoid content keeps it in the lead.

So of course: enjoy both if both are available! But if we must pick one, it’s kale.

Want to learn more?

You might like to read:

- Fight Inflammation & Protect Your Brain, With Quercetin

- Spinach vs Kale – Which is Healthier?

- Thai-Style Kale Chips (recipe)

Take care!

Don’t Forget…

Did you arrive here from our newsletter? Don’t forget to return to the email to continue learning!

Learn to Age Gracefully

Join the 98k+ American women taking control of their health & aging with our 100% free (and fun!) daily emails:

-

Is stress turning my hair grey?

10almonds is reader-supported. We may, at no cost to you, receive a portion of sales if you purchase a product through a link in this article.

When we start to go grey depends a lot on genetics.

Your first grey hairs usually appear anywhere between your twenties and fifties. For men, grey hairs normally start at the temples and sideburns. Women tend to start greying on the hairline, especially at the front.

The most rapid greying usually happens between ages 50 and 60. But does anything we do speed up the process? And is there anything we can do to slow it down?

You’ve probably heard that plucking, dyeing and stress can make your hair go grey – and that redheads don’t. Here’s what the science says.

Oksana Klymenko/Shutterstock What gives hair its colour?

Each strand of hair is produced by a hair follicle, a tunnel-like opening in your skin. Follicles contain two different kinds of stem cells:

- keratinocytes, which produce keratin, the protein that makes and regenerates hair strands

- melanocytes, which produce melanin, the pigment that colours your hair and skin.

There are two main types of melanin that determine hair colour. Eumelanin is a black-brown pigment and pheomelanin is a red-yellow pigment.

The amount of the different pigments determines hair colour. Black and brown hair has mostly eumelanin, red hair has the most pheomelanin, and blonde hair has just a small amount of both.

So what makes our hair turn grey?

As we age, it’s normal for cells to become less active. In the hair follicle, this means stem cells produce less melanin – turning our hair grey – and less keratin, causing hair thinning and loss.

As less melanin is produced, there is less pigment to give the hair its colour. Grey hair has very little melanin, while white hair has none left.

Unpigmented hair looks grey, white or silver because light reflects off the keratin, which is pale yellow.

Grey hair is thicker, coarser and stiffer than hair with pigment. This is because the shape of the hair follicle becomes irregular as the stem cells change with age.

Interestingly, grey hair also grows faster than pigmented hair, but it uses more energy in the process.

Can stress turn our hair grey?

Yes, stress can cause your hair to turn grey. This happens when oxidative stress damages hair follicles and stem cells and stops them producing melanin.

Oxidative stress is an imbalance of too many damaging free radical chemicals and not enough protective antioxidant chemicals in the body. It can be caused by psychological or emotional stress as well as autoimmune diseases.

Environmental factors such as exposure to UV and pollution, as well as smoking and some drugs, can also play a role.

Melanocytes are more susceptible to damage than keratinocytes because of the complex steps in melanin production. This explains why ageing and stress usually cause hair greying before hair loss.

Scientists have been able to link less pigmented sections of a hair strand to stressful events in a person’s life. In younger people, whose stems cells still produced melanin, colour returned to the hair after the stressful event passed.

4 popular ideas about grey hair – and what science says

1. Does plucking a grey hair make more grow back in its place?

No. When you pluck a hair, you might notice a small bulb at the end that was attached to your scalp. This is the root. It grows from the hair follicle.

Plucking a hair pulls the root out of the follicle. But the follicle itself is the opening in your skin and can’t be plucked out. Each hair follicle can only grow a single hair.

It’s possible frequent plucking could make your hair grey earlier, if the cells that produce melanin are damaged or exhausted from too much regrowth.

2. Can my hair can turn grey overnight?

Legend says Marie Antoinette’s hair went completely white the night before the French queen faced the guillotine – but this is a myth.

It is not possible for hair to turn grey overnight, as in the legend about Marie Antoinette. Yann Caradec/Wikimedia, CC BY-NC-SA Melanin in hair strands is chemically stable, meaning it can’t transform instantly.

Acute psychological stress does rapidly deplete melanocyte stem cells in mice. But the effect doesn’t show up immediately. Instead, grey hair becomes visible as the strand grows – at a rate of about 1 cm per month.

Not all hair is in the growing phase at any one time, meaning it can’t all go grey at the same time.

3. Will dyeing make my hair go grey faster?

This depends on the dye.

Temporary and semi-permanent dyes should not cause early greying because they just coat the hair strand without changing its structure. But permanent products cause a chemical reaction with the hair, using an oxidising agent such as hydrogen peroxide.

Accumulation of hydrogen peroxide and other hair dye chemicals in the hair follicle can damage melanocytes and keratinocytes, which can cause greying and hair loss.

4. Is it true redheads don’t go grey?

People with red hair also lose melanin as they age, but differently to those with black or brown hair.

This is because the red-yellow and black-brown pigments are chemically different.

Producing the brown-black pigment eumelanin is more complex and takes more energy, making it more susceptible to damage.

Producing the red-yellow pigment (pheomelanin) causes less oxidative stress, and is more simple. This means it is easier for stem cells to continue to produce pheomelanin, even as they reduce their activity with ageing.

With ageing, red hair tends to fade into strawberry blonde and silvery-white. Grey colour is due to less eumelanin activity, so is more common in those with black and brown hair.

Your genetics determine when you’ll start going grey. But you may be able to avoid premature greying by staying healthy, reducing stress and avoiding smoking, too much alcohol and UV exposure.

Eating a healthy diet may also help because vitamin B12, copper, iron, calcium and zinc all influence melanin production and hair pigmentation.

Theresa Larkin, Associate Professor of Medical Sciences, University of Wollongong

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Don’t Forget…

Did you arrive here from our newsletter? Don’t forget to return to the email to continue learning!

Learn to Age Gracefully

Join the 98k+ American women taking control of their health & aging with our 100% free (and fun!) daily emails:

-

Why do I need to take some medicines with food?

10almonds is reader-supported. We may, at no cost to you, receive a portion of sales if you purchase a product through a link in this article.

Have you ever been instructed to take your medicine with food and wondered why? Perhaps you’ve wondered if you really need to?

There are varied reasons, and sometimes complex science and chemistry, behind why you may be advised to take a medicine with food.

To complicate matters, some similar medicines need to be taken differently. The antibiotic amoxicillin with clavulanic acid (sold as Amoxil Duo Forte), for example, is recommended to be taken with food, while amoxicillin alone (sold as Amoxil), can be taken with or without food.

Different brands of the same medicine may also have different recommendations when it comes to taking it with food.

Ron Lach/Pexels Food impacts drug absorption

Food can affect how fast and how much a drug is absorbed into the body in up to 40% of medicines taken orally.

When you have food in your stomach, the makeup of the digestive juices change. This includes things like the fluid volume, thickness, pH (which becomes less acidic with food), surface tension, movement and how much salt is in your bile. These changes can impair or enhance drug absorption.

Eating a meal also delays how fast the contents of the stomach move into the small intestine – this is known as gastric emptying. The small intestine has a large surface area and rich blood supply – and this is the primary site of drug absorption.

Eating a meal with medicine will delay its onset. Farhad/Pexels Eating a larger meal, or one with lots of fibre, delays gastric emptying more than a smaller meal. Sometimes, health professionals will advise you to take a medicine with food, to help your body absorb the drug more slowly.

But if a drug can be taken with or without food – such as paracetamol – and you want it to work faster, take it on an empty stomach.

Food can make medicines more tolerable

Have you ever taken a medicine on an empty stomach and felt nauseated soon after? Some medicines can cause stomach upsets.

Metformin, for example, is a drug that reduces blood glucose and treats type 2 diabetes and polycystic ovary syndrome. It commonly causes gastrointestinal symptoms, with one in four users affected. To combat these side effects, it is generally recommended to be taken with food.

The same advice is given for corticosteroids (such as prednisolone/prednisone) and certain antibiotics (such as doxycycline).

Taking some medicines with food makes them more tolerable and improves the chance you’ll take it for the duration it’s prescribed.

Can food make medicines safer?

Ibuprofen is one of the most widely used over-the-counter medicines, with around one in five Australians reporting use within a two-week period.

While effective for pain and inflammation, ibuprofen can impact the stomach by inhibiting protective prostaglandins, increasing the risk of bleeding, ulceration and perforation with long-term use.

But there isn’t enough research to show taking ibuprofen with food reduces this risk.

Prolonged use may also affect kidney function, particularly in those with pre-existing conditions or dehydration.

The Australian Medicines Handbook, which guides prescribers about medicine usage and dosage, advises taking ibuprofen (sold as Nurofen and Advil) with a glass of water – or with a meal if it upsets your stomach.

If it doesn’t upset your stomach, ibuprofen can be taken with water. Tbel Abuseridze/Unsplash A systematic review published in 2015 found food delays the transit of ibuprofen to the small intestine and absorption, which delays therapeutic effect and the time before pain relief. It also found taking short courses of ibuprofen without food reduced the need for additional doses.

To reduce the risk of ibuprofen causing damage to your stomach or kidneys, use the lowest effective dose for the shortest duration, stay hydrated and avoid taking other non-steroidal anti-inflammatory medicines at the same time.

For people who use ibuprofen for prolonged periods and are at higher risk of gastrointestinal side effects (such as people with a history of ulcers or older adults), your prescriber may start you on a proton pump inhibitor, a medicine that reduces stomach acid and protects the stomach lining.

How much food do you need?

When you need to take a medicine with food, how much is enough?

Sometimes a full glass of milk or a couple of crackers may be enough, for medicines such as prednisone/prednisolone.

However, most head-to-head studies that compare the effects of a medicine “with food” and without, usually use a heavy meal to define “with food”. So, a cracker may not be enough, particularly for those with a sensitive stomach. A more substantial meal that includes a mix of fat, protein and carbohydrates is generally advised.

Your health professional can advise you on which of your medicines need to be taken with food and how they interact with your digestive system.

Mary Bushell, Clinical Associate Professor in Pharmacy, University of Canberra

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Don’t Forget…

Did you arrive here from our newsletter? Don’t forget to return to the email to continue learning!

Learn to Age Gracefully

Join the 98k+ American women taking control of their health & aging with our 100% free (and fun!) daily emails: