Purpose – by Gina Bianchini

10almonds is reader-supported. We may, at no cost to you, receive a portion of sales if you purchase a product through a link in this article.

To address the elephant in the room, this is not a rehash of Rick Warren’s best-selling “The Purpose-Driven Life”. Instead, this book is (in this reviewer’s opinion) a lot better. It’s a lot more comprehensive, and it doesn’t assume that what’s most important to the author will be what’s most important to you.

What’s it about, then? It’s about giving your passion (whatever it may be) the tools to have an enduring impact on the world. It recommends doing this by leveraging a technology that would once have been considered magic: social media.

Far from “grow your brand” business books, this one looks at what really matters the most to you. Nobody will look back on your life and say “what a profitable second quarter that was in such-a-year”. But if you do your thing well, people will look back and say:

- “he was a pillar of the community”

- “she raised that community around her”

- “they did so much for us”

- “finding my place in that community changed my life”

- …and so forth. Isn’t that something worth doing?

Bianchini takes the position of both “idealistic dreamer” and “realistic worker”.

Further, she blends the two beautifully, to give practical step-by-step instructions on how to give life to the community that you build.

Don’t Forget…

Did you arrive here from our newsletter? Don’t forget to return to the email to continue learning!

Recommended

Learn to Age Gracefully

Join the 98k+ American women taking control of their health & aging with our 100% free (and fun!) daily emails:

-

Intuitive Eating Might Not Be What You Think

10almonds is reader-supported. We may, at no cost to you, receive a portion of sales if you purchase a product through a link in this article.

In our recent Expert Insights main features, we’ve looked at two fairly opposing schools of thought when it comes to managing what we eat.

First we looked at:

What Flexible Dieting Really Means

…and the notion of doing things imperfectly for greater sustainability, and reducing the cognitive load of dieting by measuring only the things that are necessary.

And then in opposition to that,

What Are The “Bright Lines” Of Bright Line Eating?

…and the notion of doing things perfectly so as to not go astray, and reducing the cognitive load of dieting by having hard-and-fast rules that one does not second-guess or reconsider later when hungry.

Today we’re going to look at Intuitive Eating, and what it does and doesn’t mean.

Intuitive Eating does mean paying attention to hunger signals (each way)

Intuitive Eating means listening to one’s body, and responding to hunger signals, whether those signals are saying “time to eat” or “time to stop”.

A common recommendation is to “check in” with one’s body several times per meal, reflecting on such questions as:

- Do I have hunger pangs? Would I seek food now if I weren’t already at the table?

- If I hadn’t made more food than I’ve already eaten so far, would that have been enough, or would I have to look for something else to eat?

- Am I craving any of the foods that are still before me? Which one(s)?

- How much “room” do I feel I still have, really? Am I still in the comfort zone, and/or am I about to pass into having overeaten?

- Am I eating for pleasure only at this point? (This is not inherently bad, by the way—it’s ok to have a little more just for pleasure! But it is good to note that this is the reason we’re eating, and take it as a cue to slow down and remember to eat mindfully, and enjoy every bite)

- Have I, in fact, passed the point of pleasure, and I’m just eating because it’s in front of me, or so as to “not be wasteful”?

See also: Interoception: Improving Our Awareness Of Body Cues

And for that matter: Mindful Eating: How To Get More Out Of What’s On Your Plate

Intuitive Eating is not “80:20”

When it comes to food, the 80:20 rule is the idea of having 80% of one’s diet healthy, and the other 20% “free”, not necessarily unhealthy, but certainly not moderated either.

Do you know what else the 80:20 food rule is?

A food rule.

Intuitive Eating doesn’t do those.

The problem with food rules is that they can get us into the sorts of problems described in the studies showing how flexible dieting generally works better than rigid dieting.

Suddenly, what should have been our free-eating 20% becomes “wait, is this still 20%, or have I now eaten so much compared to the healthy food, that I’m at 110% for my overall food consumption today?”

Then one gets into “Well, I’ve already failed to do 80:20 today, so I’ll try again tomorrow [and binge meanwhile, since today is already written off]”

See also: Eating Disorders: More Varied (And Prevalent) Than People Think

It’s not “eat anything, anytime”, either

Intuitive Eating is about listening to your body, and your brain is also part of your body.

- If your body is saying “give me sugar”, your brain might add the information “fruit is healthier than candy”.

- If your body is saying “give me fat”, your brain might add the information “nuts are healthier than fried food”

- If your body is saying “give me salt”, your brain might add the information “kimchi is healthier than potato chips”

That doesn’t mean you have to swear off candy, fried food, or potato chips.

But it does mean that you might try satisfying your craving with the healthier option first, giving yourself permission to have the less healthy option afterwards if you still want it (you probably won’t).

See also:

I want to eat healthily. So why do I crave sugar, salt and carbs?

Want to know more about Intuitive Eating?

You might like this book that we reviewed previously:

Intuitive Eating – by Evelyn Tribole and Elyse Resch

Enjoy!

Share This Post

-

Cognitive Enhancement Without Drugs

10almonds is reader-supported. We may, at no cost to you, receive a portion of sales if you purchase a product through a link in this article.

Cognitive Enhancement Without Drugs

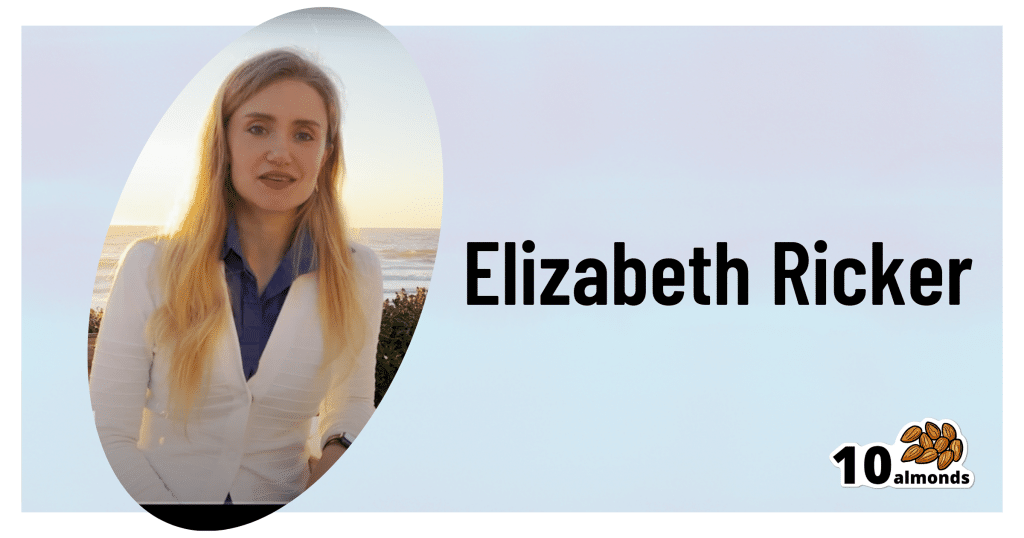

This is Elizabeth Ricker. She’s a Harvard-and-MIT-trained neuroscientist and researcher, who now runs the “Citizen Science” DIY-neurohacking organization, NeuroEducate.

Sounds fun! What’s it about?

The philosophy that spurs on her research and practice can be summed up as follows:

❝I’m not going to leave my brain up to my doctor or [anyone else]… My brain is my own responsibility, and I’m going to do the best that I can to optimize it❞

Her goal is not just to optimize her own brain though; she wants to make the science accessible to everyone.

What’s this about Citizen Science?

“Citizen Science” is the idea that while there’s definitely an important role in society for career academics, science itself should be accessible to all. And, not just the conclusions, but the process too.

This can take the form of huge experiments, often facilitated these days by apps where we opt-in to allow our health metrics (for example) to be collated with many thousands of others, for science. It can also involve such things as we talked about recently, getting our own raw genetic data and “running the numbers” at home to get far more comprehensive and direct information than the genetic testing company would ever provide us.

For Ricker, her focus is on the neuroscience side of biohacking, thus, neurohacking.

I’m ready to hack my brain! Do I need a drill?

Happily not! Although… Bone drills for the skull are very convenient instruments that make it quite hard to go wrong even with minimal training. The drill bit has a little step/ledge partway down, which means you can only drill through the thickness of the skull itself, before the bone meeting the wider part of the bit stops you from accidentally drilling into the brain. Still, please don’t do this at home.

What you can do at home is a different kind of self-experimentation…

If you want to consider which things are genuinely resulting in cognitive enhancement and which things are not, you need to approach the matter like a scientist. That means going about it in an organized fashion, and recording results.

There are several ways cognitive enhancement can be measured, including:

- Learning and memory

- Executive function

- Emotional regulation

- Creative intelligence

Let’s look at each of them, and what can be done. We don’t have a lot of room here; we’re a newsletter not a book, but we’ll cover one of Ricker’s approaches for each:

Learning and memory

This one’s easy. We’re going to leverage neuroplasticity (neurons that fire together, wire together!) by simple practice, and introduce an extra element to go alongside your recall. Perhaps a scent, or a certain item of clothing. Tell yourself that clinical studies have shown that this will boost your recall. It’s true, but that’s not what’s important; what’s important is that you believe it, and bring the placebo effect to bear on your endeavors.

You can test your memory with word lists, generated randomly by AI, such as this one:

You’ll soon find your memory improving—but don’t take our word for it!

Executive function

Executive function is the aspect of your brain that tells the other parts how to work, when to work, and when to stop working. If you’ve ever spent 30 minutes thinking “I need to get up” but you were stuck in scrolling social media, that was executive dysfunction.

This can be trained using the Stroop Color and Word Test, which shows you words, specifically the names of colors, which will themselves be colored, but not necessarily in the color the word pertains to. So for example, you might be shown the word “red”, colored green. Your task is to declare either the color of the word only, ignoring the word itself, or the meaning of the word only, ignoring its appearance. It can be quite challenging, but you’ll get better quite quickly:

The Stroop Test: Online Version

Emotional Regulation

This is the ability to not blow up angrily at the person with whom you need to be diplomatic, or to refrain from laughing when you thought of something funny in a sombre situation.

It’s an important part of cognitive function, and success or failure can have quite far-reaching consequences in life. And, it can be trained too.

There’s no online widget for this one, but: when and if you’re in a position to safely* do so, think about something that normally triggers a strong unwanted emotional reaction. It doesn’t have to be something life-shattering, but just something that you feel in some way bad about. Hold this in your mind, sit with it, and practice mindfulness. The idea is to be able to hold the unpleasant idea in your mind, without becoming reactive to it, or escaping to more pleasant distractions. Build this up.

*if you perchance have PTSD, C-PTSD, or an emotional regulation disorder, you might want to talk this one through with a qualified professional first.

Creative Intelligence

Another important cognitive skill, and again, one that can be cultivated and grown.

The trick here is volume. A good, repeatable test is to think of a common object (e.g. a rock, a towel, a banana) and, within a time constraint (such as 15 minutes) list how many uses you can think of for that item.

Writer’s storytime: once upon a time, I was sorting through an inventory of medical equipment with a colleague, and suggested throwing out our old arterial clamps, as we had newer, better ones—in abundance. My colleague didn’t want to part with them, so I challenged him “Give me one use for these, something we could in some possible world use them for that the new clamps don’t do better, and we’ll keep them”. He said “Thumbscrews”, and I threw my hands up in defeat, saying “Fine!”, as he had technically fulfilled my condition.

What’s the hack to improve this one? Just more volume. Creativity, as it turns out, isn’t something we can expend—like a muscle, it grows the more we use it. And because the above test is repeatable (with different objects), you can track your progress.

And if you feel like using your grown creative muscle to write/paint/compose/etc your magnum opus, great! Or if you just want to apply it to the problem-solving of everyday life, also great!

In summary…

Our brain is a wonderful organ with many functions. Society expects us to lose these as we get older, but the simple, scientific truth is that we can not only maintain our cognitive function, but also enhance and grow it as we go.

Want to know more from today’s featured expert?

You might enjoy her book, “Smarter Tomorrow”, which we reviewed back in March

Share This Post

-

End the Insomnia Struggle – by Dr. Colleen Ehrnstrom and Dr. Alisha Brosse

10almonds is reader-supported. We may, at no cost to you, receive a portion of sales if you purchase a product through a link in this article.

We’ve reviewed sleep books before, and we always try to recommend books that have something a little different than the rest, so what makes this one stand out?

While there is the usual quick overview of the basics that we’re sure you already know (sleep hygiene etc), most of the attention here is given to cold, hard clinical psychology… in a highly personalized way.

How, you may ask, can they personalize a book, that is the same for everyone?

The answer is, by guiding the reader through examining our own situation. With template logbooks, worksheets, and the like—for this reason we recommend getting a paper copy of the book, rather than the Kindle version, in case you’d like to use/photocopy those.

Essentially, reading this book is much like having your own psychologist (or two) to guide you through finding a path to better sleep.

The therapeutic approach, by the way, is a combination of Cognitive Behavioral Therapy (CBT) and Acceptance-Commitment Therapy (ACT), which work very well together here.

Bottom line: if you’ve changed your bedsheets and turned off your electronic devices and need something a little more, this book is the psychological “big guns” for removing the barriers between you and good sleep.

Click here to check out End the Insomnia Struggle, and end yours once and for all!

Share This Post

Related Posts

-

Your Science-Based Guide To Losing Fat & Toning Up

10almonds is reader-supported. We may, at no cost to you, receive a portion of sales if you purchase a product through a link in this article.

This health coach researched the science and crunched the numbers so that you don’t have to:

Body by the numbers

Let’s get mathematical:

Total Daily Energy Expenditure (TDEE) consists of:

- Basal Metabolic Rate (BMR): 70% of daily calorie burn (basic body functions, of which the brain is the single biggest calorie-burner)

- Non-Exercise Activity Thermogenesis (NEAT): 15% (the normal movements that occur as you go about your daily life)

- Exercise Activity: 5% (actual workouts, often overestimated)

- Thermic Effect of Food (TEF): 10% (energy needed for digestion)

Basic BMR estimate:

- Women: body weight (kg) × 0.9 × 24

- Men: body weight (kg) × 24

But yours may differ, so if you have a fitness tracker or other gadget that estimates it for you, go with that!

Note: muscle burns calories just to maintain it, making muscle mass crucial to increasing one’s BMR.

And now some notes about running a caloric deficit:

- Safe caloric deficit: no more than 500 calories/day.

- Absolute minimum daily intake: 1,200 calories (women), 1,500 calories (men) (not sustainable long-term).

- Tracking calories is useful but not always accurate.

- Extreme calorie restriction slows metabolism and can lead to binge-eating.

- Your body will adjust to calorie deficits over time, making long-term drastic deficits ineffective.

Diet for fat loss & muscle gain:

- Protein Intake: 1.5–2g per pound of body weight.

- Aim for 30g of protein per meal (supports muscle & satiety).

- Protein has a higher thermic effect (20-30%) than carbs (5-10%) & fats (2-4%), meaning more calories are burned digesting protein.

- Fats are essential for hormone health & satiety (0.5–1g per kg of body weight).

- Carbs should be complex (whole grains, vegetables, fruits, etc.).

- Avoid excessive simple carbs (sugar, white bread, white pasta, etc) to maintain stable hunger signals.

- Hydration is key for appetite control & metabolism (often mistaken for hunger).

Exercise for fat loss & muscle gain:

- Resistance training (3-5x per week) is essential for toning & metabolism.

- Cardio is NOT necessary for fat loss but good for overall health.

- NEAT (non-exercise movement) burns significant calories (walking, taking stairs, fidgeting, etc.).

- “Hot girl walks” & daily movement can significantly aid weight loss.

- Women won’t get “bulky” from weight training unless they eat like a bodybuilder (i.e. several times the daily caloric requirement).

Some closing words in addition:

Poor sleep reduces fat loss by 50% and increases hunger. High stress levels lead to fat retention and cravings for unhealthy foods. Thus, managing stress & sleep is as important as diet & exercise for body transformation!

For more on all of this (plus the sources for the science), enjoy:

Click Here If The Embedded Video Doesn’t Load Automatically!

Want to learn more?

You might also like to read:

How To Lose Weight (Healthily) ← our own main feature about such; we took a less numbers-based, more principles-based, approach. Both approaches work, so go with whichever suits your personal preference more!

Take care!

Don’t Forget…

Did you arrive here from our newsletter? Don’t forget to return to the email to continue learning!

Learn to Age Gracefully

Join the 98k+ American women taking control of their health & aging with our 100% free (and fun!) daily emails:

-

Aging For Beginners – by Ezra Bayda & Elizabeth Hamilton

10almonds is reader-supported. We may, at no cost to you, receive a portion of sales if you purchase a product through a link in this article.

This one’s not about how to avoid aging, but rather, how to be at peace with whatever aging may be happening, perhaps despite our best efforts.

The book is dedicated:

❝To all the starving and suffering children throughout the world, with the wish that they may someday have the opportunity to experience the life of a contented geriatric❞

It’s a stark reminder that old age is a privilege that many do not get to enjoy, thanks to poverty, disease, wars, and accidents and incidents along the way.

So, how to go about making the very most of what we have, for those of us who are perhaps going gray in a comfortable, safe environment?

The answer may surprise you: the authors tackle things head-on without dressing old age up in euphemisms or platitudes—they cover not just the physical decline that typically occurs eventually, but also the impact of the physical pain that this may bring, the way this may play into loneliness and helplessness, and perhaps anxiety and/or depression. And, of course, the topic of grief and loss, that for most of us becomes all the more part of our lives as we get older. For that matter, our own mortality is also something the authors come back to from start to finish.

Thus, this is not necessarily a cheerful book—but it gives the tools such that we can be cheerful about life in general, in the face of all the aforementioned things, without pretending that things that are not good are good, just, making our peace with what is, and making the most out of what we have.

The authors are Zen teachers with decades of experience, and this book is heavily influenced by Zen principles. And yes, it does teach meditation too, but that’s just one tool in the toolbox.

The style is deep and yet very readable, heavy of tone and at the same time inspiring of lightness of heart.

Bottom line: if you’d like to worry less about aging (while still doing all you want to stay young), this book can certainly help with that.

Click here to check out Aging For Beginners, and be at peace with yourself.

Don’t Forget…

Did you arrive here from our newsletter? Don’t forget to return to the email to continue learning!

Learn to Age Gracefully

Join the 98k+ American women taking control of their health & aging with our 100% free (and fun!) daily emails:

-

The Best Foods For Collagen Production

10almonds is reader-supported. We may, at no cost to you, receive a portion of sales if you purchase a product through a link in this article.

Dr. Andrea Suarez gives us the low-down on collagen synthesis and maintenance. Collagen is the most abundant protein in our body, and it can be fairly described as “the stuff that holds us together”. It’s particularly important for joints and bones too, though many people’s focus on it is for the skin. Whatever your priorities, collagen levels are something it pays to be mindful of, as they usually drop quite sharply after a certain age. What certain age? Well, that depends a lot on you, and your diet and lifestyle. But it can start to decline from the age of 30 with often noticeable drop-offs in one’s mid-40s and again in one’s mid-60s.

Showing us what we’re made of

There’s a lot more to having good collagen levels than just how much collagen we consume (which for vegetarians/vegans, will be “none”, unless using the “except if for medical reasons” exemption, which is probably a little tenuous in the case of collagen but nevertheless it’s a possibility; this exemption is usually one that people use for, say, a nasal spray vaccine that contains gelatine, or a medicinal tablet that contains lactose, etc).

Rather, having good collagen levels is also a matter of what we eat that allows us to synthesize our own collagen (which includes: its ingredients, and various “helper” nutrients), as well as what dietary adjustments we make to avoid our extant collagen getting broken down, degraded, and generally lost.

Here’s what Dr. Suarez recommends:

Protein-rich foods (but watch out)

- Protein is essential for collagen production.

- Sources: fish, soy, lean meats (but not red meats, which—counterintuitively—degrade collagen), eggs, lentils.

- Egg whites are high in lysine, vital for collagen synthesis.

- Bone broth is a natural source of collagen.

Omega-3 fatty acids

- Omega-3s are anti-inflammatory and protect skin collagen.

- Sources: walnuts, chia seeds, flax seeds, fatty fish (e.g. mackerel, sardines).

Leafy greens

- Leafy dark green vegetables (e.g. kale, spinach) are rich in vitamins C and B9.

- Vitamin C is crucial for collagen synthesis and acts as an antioxidant.

- Vitamin B9 supports skin cell division and DNA repair.

Red fruits & vegetables

- Red fruits/vegetables (e.g. tomatoes, red bell peppers) contain lycopene, an antioxidant that protects collagen from UV damage (so, that aspect is mostly relevant for skin, but antioxidants are good things to have in all of the body in any case).

Orange-colored vegetables

- Carrots and sweet potatoes are rich in vitamin A, which helps in collagen repair and synthesis.

- Vitamin A is best from food, not supplements, to avoid potential toxicity.

Fruits rich in vitamin C

- Citrus fruits, kiwi, and berries are loaded with vitamin C and antioxidants, essential for collagen synthesis and skin health.

Soy

- Soy products (e.g. tofu, soybeans) contain isoflavones, which reduce inflammation and inhibit enzymes that degrade collagen.

- Soy is associated with lower risks of chronic diseases.

Garlic

- Garlic contains sulfur, taurine, and lipoic acid, important for collagen production and repair.

What to avoid:

- Reduce foods high in advanced glycation end products (AGEs), which damage collagen and promote inflammation.

- AGEs are found in fried, roasted, or grilled fatty proteinous foods (e.g. meat, including synthetic meat, and yes, including grass-fed nicely marketed meat—although processed meat such as bacon and sausages are even worse than steaks etc).

- Switch to cooking methods like boiling or steaming to reduce AGE levels.

- Processed foods, sugary pastries, and red meats contribute to collagen degradation.

General diet tips:

- Incorporate more plant-based, antioxidant-rich foods.

- Opt for slow cooking to reduce AGEs.

- Since sustainability is key, choose foods you enjoy for a collagen-boosting diet that you won’t seem like a chore a month later.

For more on all of this, enjoy:

Click Here If The Embedded Video Doesn’t Load Automatically!

Want to learn more?

You might also like to read:

We Are Such Stuff As Fish Are Made Of ← our main feature research review about collagen

Take care!

Don’t Forget…

Did you arrive here from our newsletter? Don’t forget to return to the email to continue learning!

Learn to Age Gracefully

Join the 98k+ American women taking control of their health & aging with our 100% free (and fun!) daily emails: