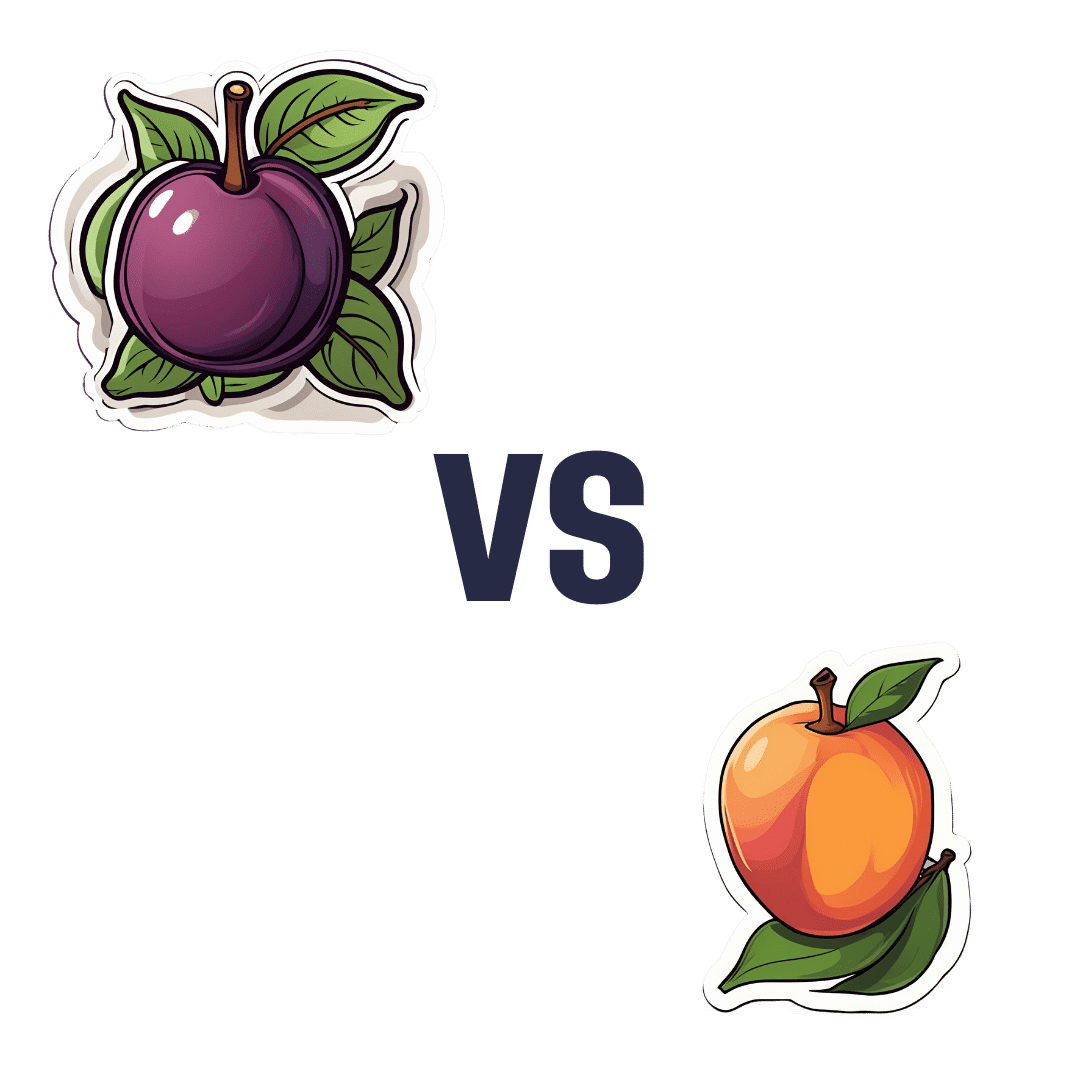

Plum vs Nectarine – Which is Healthier?

10almonds is reader-supported. We may, at no cost to you, receive a portion of sales if you purchase a product through a link in this article.

Our Verdict

When comparing plums to nectarines, we picked the nectarines.

Why?

Both are great! But nectarines win at least marginally in each category we look at.

In terms of macros, plums have more carbs while nectarines have more fiber, resulting of course in a lower glycemic index. Plums do have a low GI also; just, nectarines have it better.

When it comes to vitamins, plums have more of vitamins A, B6, C, and K, while nectarines have more of vitamins B1, B2, B3, B5, E, and choline.

In the category of minerals, plums are great but not higher in any mineral than nectarines; nectarines meanwhile have more copper, iron, magnesium, manganese, phosphorus, potassium, and zinc.

All in all, enjoy both. And if having dried fruit, then prunes (dried plums) are generally more widely available than dried nectarines. But if you’re choosing one fruit or the other, nectarine is the way to go.

Want to learn more?

You might like to read:

- Why You’re Probably Not Getting Enough Fiber (And How To Fix It)

- Replacing Sugar: Top 10 Anti-Inflammatory Sweet Foods

- Top 8 Fruits That Prevent & Kill Cancer

Take care!

Don’t Forget…

Did you arrive here from our newsletter? Don’t forget to return to the email to continue learning!

Recommended

Learn to Age Gracefully

Join the 98k+ American women taking control of their health & aging with our 100% free (and fun!) daily emails:

-

Stop Cancer 20 Years Ago

10almonds is reader-supported. We may, at no cost to you, receive a portion of sales if you purchase a product through a link in this article.

Get Abreast And Keep Abreast

This is Dr. Jenn Simmons. Her specialization is integrative oncology, as she—then a breast cancer surgeon—got breast cancer, decided the system wasn’t nearly as good from the patients’ side of things as from the doctors’ side, and took to educate herself, and now others, on how things can be better.

What does she want us to know?

Start now

If you have breast cancer, the best time to start adjusting your lifestyle might be 20 years ago, but the second-best time is now. We realize our readers with breast cancer (or a history thereof) probably have indeed started already—all strength to you.

What this means for those of us without breast cancer (or a history therof) is: start now

Even if you don’t have a genetic risk factor, even if there’s no history of it in your family, there’s just no reason not to start now.

Start what, you ask? Taking away its roots. And how?

Inflammation as the root of cancer

To oversimplify: cancer occurs because an accidentally immortal cell replicates and replicates and replicates and takes any nearby resources to keep on going. While science doesn’t know all the details of how this happens, it is a factor of genetic mutation (itself a normal process, without which evolution would be impossible), something which in turn is accelerated by damage to the DNA. The damage to the DNA? That occurs (often as not) as a result of cellular oxidation. Cellular oxidation is far from the only genotoxic thing out there, and a lot of non-food “this thing causes cancer” warnings are usually about other kinds of genotoxicity. But cellular oxidation is a big one, and it’s one that we can fight vigorously with our lifestyle.

Because cellular oxidation and inflammation go hand-in-hand, reducing one tends to reduce the other. That’s why so often you’ll see in our Research Review Monday features, a line that goes something like:

“and now for those things that usually come together: antioxidant, anti-inflammatory, anticancer, and anti-aging”

So, fight inflammation now, and have a reduced risk of a lot of other woes later.

See: How to Prevent (or Reduce) Inflammation

Don’t settle for “normal”

People are told, correctly but not always helpfully, such things as:

- It’s normal to have less energy at your age

- It’s normal to have a weaker immune system at your age

- It’s normal to be at a higher risk of diabetes, heart disease, etc

…and many more. And these things are true! But that doesn’t mean we have to settle for them.

We can be all the way over on the healthy end of the distribution curve. We can do that!

(so can everyone else, given sufficient opportunity and resources, because health is not a zero-sum game)

If we’re going to get a cancer diagnosis, then our 60s are the decade where we’re most likely to get it. Earlier than that and the risk is extant but lower; later than that and technically the risk increases, but we probably got it already in our 60s.

So, if we be younger than 60, then now’s a good time to prepare to hit the ground running when we get there. And if we missed that chance, then again, the second-best time is now:

See: Focusing On Health In Our Sixties

Fast to live

Of course, anything can happen to anyone at any age (alas), but this is about the benefits of living a fasting lifestyle—that is to say, not just fasting for a 4-week health kick or something, but making it one’s “new normal” and just continuing it for life.

This doesn’t mean “never eat”, of course, but it does mean “practice intermittent fasting, if you can”—something that Dr. Simmons strongly advocates.

See: Intermittent Fasting: We Sort The Science From The Hype

While this calls back to the previous “fight inflammation”, it deserves its own mention here as a very specific way of fighting it.

It’s never too late

All of the advices that go before a cancer diagnosis, continue to stand afterwards too. There is no point of “well, I already have cancer, so what’s the harm in…?”

The harm in it after a diagnosis will be the same as the harm before. When it comes to lifestyle, preventing a cancer and preventing it from spreading are very much the same thing, which is also the same as shrinking it. Basically, if it’s anticancer, it’s anticancer, no matter whether it’s before, during, or after.

Dr. Simmons has seen too many patients get a diagnosis, and place their lives squarely in the hands of doctors, when doctors can only do so much.

Instead, Dr. Simmons recommends taking charge of your health as best you are able, today and onwards, no matter what. And that means two things:

- Knowing stuff

- Doing stuff

So it becomes our responsibility (and our lifeline) to educate ourselves, and take action accordingly.

Want to know more?

We recently reviewed her book, and heartily recommend it:

The Smart Woman’s Guide to Breast Cancer – by Dr. Jenn Simmons

Enjoy!

Share This Post

-

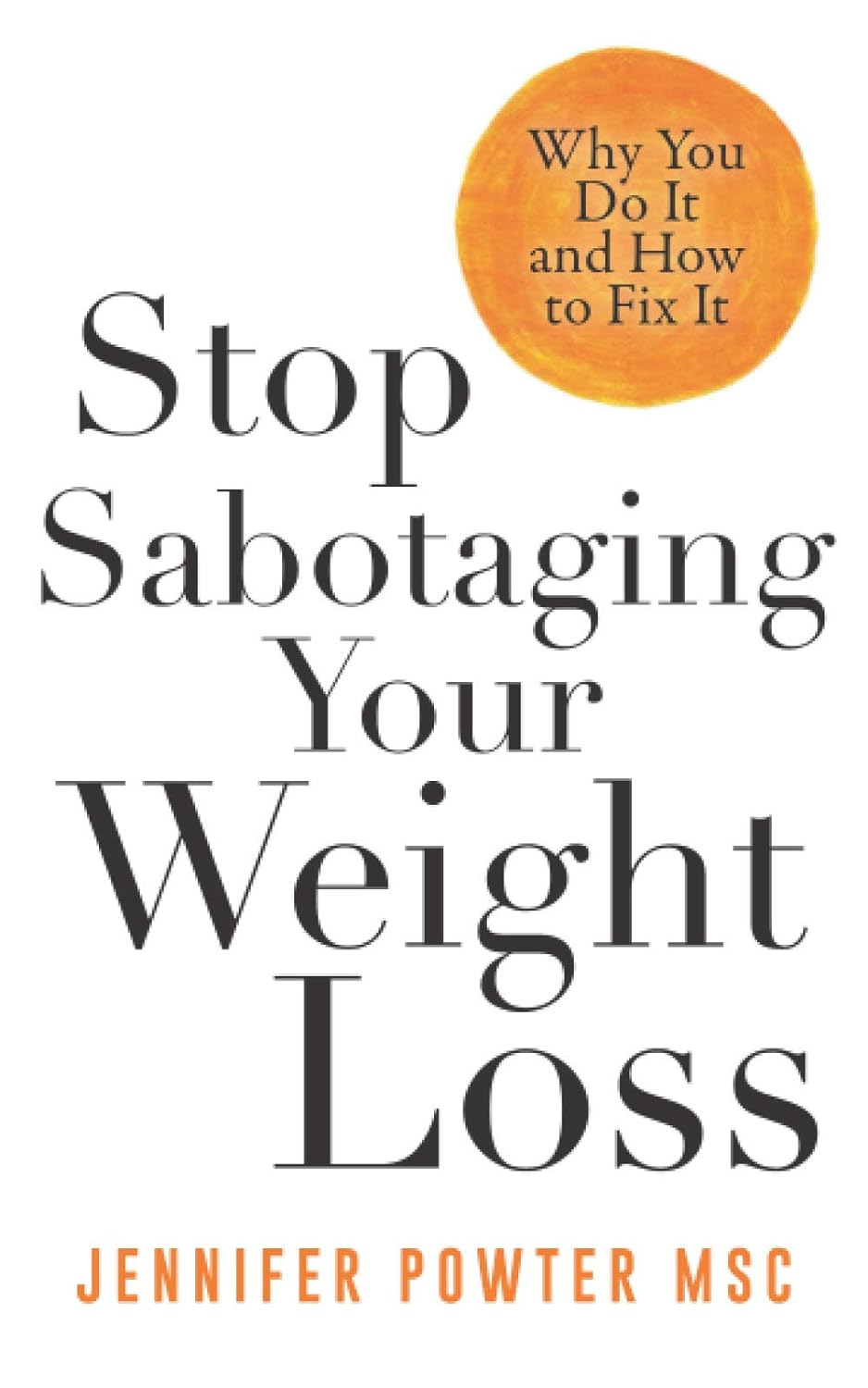

Stop Sabotaging Your Weight Loss – by Jennifer Powter, MSc

10almonds is reader-supported. We may, at no cost to you, receive a portion of sales if you purchase a product through a link in this article.

This is not a dieting book, and it’s not a motivational pep talk.

The book starts with the assumption that you do want to lose weight (it also assumes you’re a woman, and probably over 40… that’s just the book’s target market, but the same advice is good even if that’s not you), and that you’ve probably been trying, on and off, for a while. Her position is simple:

❝I don’t believe that you have a weight loss problem. I believe that you have a self-sabotage problem❞

As to how this sabotage may be occurring, Powter talks about fears that may be holding you back, including but not limited to:

- Fear of failure

- Fear of the unknown

- Fear of loss

- Fear of embarrassment

- Fear of your weight not being the reason your life sucks

Far from putting the reader down, though, Powter approaches everything with compassion. To this end, her prescription starts with encouraging self-love. Not when you’re down to a certain size, not when you’re conforming perfectly to a certain diet, but now. You don’t have to be perfect to be worthy of love.

On the topic of perfection: a recurring theme in the book is the danger of perfectionism. In her view, perfectionism is nothing more nor less than the most justifiable way to hold yourself back in life.

Lastly, she covers mental reframes, with useful questions to ask oneself on a daily basis, to ensure progressing step by step into your best life.

In short: if you’d like to lose weight and have been trying for a while, maybe on and off, this book could get you out of that cycle and into a much better state of being.

Get your copy of “Stop Sabotaging Your Weight Loss” from Amazon today!

Share This Post

-

Science of Pilates – by Tracy Ward

10almonds is reader-supported. We may, at no cost to you, receive a portion of sales if you purchase a product through a link in this article.

We’ve reviewed other books in this series, “Science of Yoga” and “Science of HIIT” (they’re great too; check them out!). What does this one add to the mix?

Pilates is a top-tier “combination exercise” insofar as it checks a lot of boxes, e.g:

- Strength—especially core strength, but also limbs

- Mobility—range of motion and resultant reduction in injury risk

- Stability—impossible without the above two things, but Pilates trains this too

- Fitness—many dynamic Pilates exercises can be performed as cardio and/or HIIT.

The author, a physiotherapist, explains (as the title promises!) the science of Pilates, with:

- the beautifully clear diagrams we’ve come to expect of this series,

- equally clear explanations, with a great balance of simplicity of terms and depth where necessary, and

- plenty of citations for the claims made, linking to lots of the best up-to-date science.

Bottom line: if you are in a position to make a little time for Pilates (if you don’t already), then there is nobody who would not benefit from reading this book.

Click here to check out Science of Pilates, and keep your body well!

Share This Post

Related Posts

-

Exhausted To Energized – by Dr. Libby Weaver

10almonds is reader-supported. We may, at no cost to you, receive a portion of sales if you purchase a product through a link in this article.

There are very many possible causes of low energy; some are obvious; some are not.

Dr. Weaver goes through a comprehensive list that goes beyond the common, to encompass also the “not rare” options—how to test for them where appropriate, and how to improve/fix them where appropriate.

Thus, she talks us through the marvels of mitochondria (including how to keep them happy and healthy and how to promote the generation of new ones), antioxidant defense mechanisms, coenzyme Q10 and friends, B vitamins of various kinds, macronutrients, the autonomic nervous system, sleep and its many factors, blood oxygenation, digestive issues, what’s going on in the spleen, the gallbladder, the liver, the kidneys, the adrenal glands, our thyroid goings-on in all its multifarious wonders, minerals like iodine, iron, magnesium, zinc, our epigenetic factors, and even psychological considerations ranging from stress to grief. In short—and we have shortened the list to pick out particularly salient points—quite a comprehensive rundown of the human body to make your human body less run-down.

The style is on the very readable pop-science, and/but she does bring her professional knowledge to bear on topic (her doctorate is a PhD in biochemistry, and it shows; a lot of explanations come from that angle).

Bottom line: if you are often exhausted and would rather be energized, this this book almost certainly address at least a couple of things you probably haven’t considered—and even just one would make it worthwhile.

Click here to check out Exhausted To Energized, go from exhausted to energized!

Don’t Forget…

Did you arrive here from our newsletter? Don’t forget to return to the email to continue learning!

Learn to Age Gracefully

Join the 98k+ American women taking control of their health & aging with our 100% free (and fun!) daily emails:

-

Sarah Raven’s Garden Cookbook – by Sarah Raven

10almonds is reader-supported. We may, at no cost to you, receive a portion of sales if you purchase a product through a link in this article.

Note: the US Amazon site currently (incorrectly) lists the author as “Jonathan Buckley”. The Canadian, British, and Australian sites all list the author correctly as Sarah Raven, and some (correctly) credit Jonathan Buckley as the photographer she used.

First, what it’s not: a gardening book. Beyond a few helpful tips, pointers, and “plant here, harvest here” instructions, this book assumes you are already capable of growing your own vegetables.

She does assume you are in a temperate climate, so if you are not, this might not be the book for you. Although! The recipes are still great; it’s just you’d have to shop for the ingredients and they probably won’t be fresh local produce for the exact same reason that you didn’t grow them.

If you are in a temperate climate though, this will take you through the year of seasonal produce (if you’re in a temperate climate but it’s in for example Australia, you’ll need to make a six-month adjustment for being in the S. Hemisphere), with many recipes to use not just one ingredient from your garden at a time, but a whole assortment, consistent with the season.

About the recipes: they (which are 450 in number) are (as you might imagine) very plant-forward, but they’re generally not vegan and often not vegetarian. So, don’t expect that you’ll produce everything yourself—just most of the ingredients!

Bottom line: if you like cooking, and are excited by the idea of growing your own food but are unsure how regularly you can integrate that, this book will keep you happily busy for a very long time.

Click here to check out Sarah Raven’s Garden Cookbook, and level-up your home cooking!

Don’t Forget…

Did you arrive here from our newsletter? Don’t forget to return to the email to continue learning!

Learn to Age Gracefully

Join the 98k+ American women taking control of their health & aging with our 100% free (and fun!) daily emails:

-

The Dopamine Myth

10almonds is reader-supported. We may, at no cost to you, receive a portion of sales if you purchase a product through a link in this article.

The Dopamine Myth

There’s a popular misconception that, since dopamine is heavily involved in addictions, it’s the cause.

We see this most often in the context of non-chemical addictions, such as:

- gambling

- videogames

- social media

And yes, those things will promote dopamine production, and yes, that will feel good. But dopamine isn’t the problem.

Myth: The Dopamine Detox

There’s a trend we’ve mentioned before (it got a video segment a few Fridays back) about the idea of a “dopamine detox“, and how unscientific the idea is.

For a start…

- You cannot detox from dopamine, because dopamine is not a toxin

- You cannot abstain from dopamine, because your brain regulates your dopamine levels to keep them correct*

- If you could abstain from dopamine (and did), you would die, horribly.

*unless you have a serious mental illness, for example:

- forms of schizophrenia and/or psychosis that involve too much dopamine, or

- forms of depression and/or neurodegenerative diseases such as Parkinson’s (and several kinds of dementia) in which you have too little dopamine

- bipolar disorder in which dopamine levels can swing too far each way

See also: Dopamine fasting: misunderstanding science spawns a maladaptive fad

Myth: Dopamine is all about pleasure

Dopamine is a pleasure-giving neurotransmitter, but it serves more purposes than that! It also plays a central role in many neurological processes, including:

- Motivation

- Learning and memory

- Motor functions

- Language faculties

- Linear task processing

Note for example how someone taking dopaminergic drugs (prescription or otherwise; could be anything from modafinil to cocaine) is not blissed out… They’re probably in a good mood, sure, but they’re focused, organized, quick-thinking, and so forth! This is not an ad for cocaine; cocaine is very bad for the health. But you see the features? So, what if we could have a little more dopamine… healthily?

Dopamine—à la carte

Let’s look at the examples we gave earlier of non-chemical addictions that are dopaminergic in nature:

- gambling

- videogames

- social media

They’re not actually that rewarding, are they?

- Gamblers lose more than they win

- Gamers cease to care about a game once they have won

- Social media more often results in “doomscrolling”

This is because what prompts the most dopamine is actually the anticipation of reward… not the thing itself, whose reward-pleasure is very fleeting. Nobody looks back at an hour of doomscrolling and thinks “well, that was fun; I’m glad I did that”.

See the science: Liking, Wanting and the Incentive-Sensitization Theory of Addiction

But what if we anticipated a reward from things that are not deleterious to health and productivity? Things that are neutral, or even good for us?

Examples of this include:

- Sex! (remember though, it’s not a race to the finish-line)

- Good, nourishing food (bonus: some foods boost dopamine production nutritionally)

- Exercise/sport (also prompts release of endorphins, win/win!)

- Gamified learning apps (e.g. Duolingo)

- Gamified health/productivity apps (anything with bells and whistles and things that go “ding” and measure streaks etc)

Want to know more?

That’s all we have time for today, but you might want to check out:

10 Best Ways to Increase Dopamine Levels Naturally ← Science-based and well-sourced article!

Don’t Forget…

Did you arrive here from our newsletter? Don’t forget to return to the email to continue learning!

Learn to Age Gracefully

Join the 98k+ American women taking control of their health & aging with our 100% free (and fun!) daily emails: