Plant-Based Salmon Recipe

10almonds is reader-supported. We may, at no cost to you, receive a portion of sales if you purchase a product through a link in this article.

From Tofu to Salmon

This video (below) by SweetPotatoSoul isn’t just a recipe tutorial; it’s an inspiring journey into the world of vegan cooking, proving that reducing animal products doesn’t have to mean sacrificing flavor.

The key to her vegan salmon is the tofu. However, there’s a trick to the tofu – you have to press it.

Essentially, this involved putting some paper towel on either side of the tofu, and then placing a heavy object on top; this removes excess water and, more importantly, primes the tofu to absorb the flavor of your marinade!

(You’ll want to press the tofu for around 1 hour)

Find the rest of the recipe in the 12-minute video below!

Other Plant-Based Recipes

With there being so many benefits of cutting meat out of your diet, we’ve spent the time reviewing some of the top books on vegan recipes, including The Green Roasting Tin and The Vegan Instant Pot Cookbook. We hope you enjoy them as much as you’ll enjoy this recipe:

How was the video? If you’ve discovered any great videos yourself that you’d like to share with fellow 10almonds readers, then please do email them to us!

Don’t Forget…

Did you arrive here from our newsletter? Don’t forget to return to the email to continue learning!

Recommended

Learn to Age Gracefully

Join the 98k+ American women taking control of their health & aging with our 100% free (and fun!) daily emails:

-

Getting COMFY – by Jordan Gross

10almonds is reader-supported. We may, at no cost to you, receive a portion of sales if you purchase a product through a link in this article.

It’s easy to see how good “morning people” seem to have it; it’s harder, it seems, to become one.

And, if we’re forced by circumstance to be the morning person we’re not? We all-too-easily find ourselves greeting each coming day without the joy that, in an ideal world, we might.

So, is it possible to learn this power? Jordan Gross has it mapped out for it us…

The “COMFY” of the title is indeed an acronym, and it stands for:

- Calm

- Openness

- Movement

- Funny

- You

There’s a chapter explaining each in detail, and they’re bookended with other chapters explaining more about the whys and the hows.

As you might expect, the key to a good morning starts the night before, but there’s also a formula to follow. Of course, you can change it up, mix and match if you like… but this book provides a base framework to build from, which is something that can make a huge difference!

Bottom line: it’s a highly enjoyable book to read, and also provides genuine powerful help to bring us the brighter happier mornings we deserve—the set-up to the perfect day!

Click here to check out “Getting COMFY” and perk up your mornings—you deserve it!

Share This Post

-

Body Language (In The Real World)

10almonds is reader-supported. We may, at no cost to you, receive a portion of sales if you purchase a product through a link in this article.

Forget What You Think You Know About Body Language

…unless it’s about a specific person whose habits and mannerisms you know intimately, in which case, you probably have enough personal data stored up to actually recognize patterns à la “when my spouse does this, then…”, and probably do know what’s going on.

For everyone else… our body language can be as unique as our idiolect

What’s an idiolect? It’s any one given person’s way of speaking/writing, in their natural state (i.e. without having to adjust their style for some reason, for example in a public-facing role at work, where style often becomes much narrower and more consciously-chosen).

Extreme example first

To give an extreme example of how non-verbal communication can be very different than a person thinks, there’s an anecdote floating around the web of someone whose non-verbal autistic kid would, when he liked someone who was visiting the house, hide their shoes when they were about to leave, to cause them to stay longer. Then one day some relative visited and when she suggested that she “should be going sometime soon”, he hurried to bring her her shoes. She left, happy that the kid liked her (he did not).

The above misunderstanding happened because the visitor had the previous life experience of “a person who brings me things is being helpful, and if they do it of their own free will, it’s because they like me”.

In other words…

Generalizations are often sound… In general

…which does not help us when dealing with individuals, which as it turns out, everyone is.

Clenched fists = tense and angry… Except when it’s just what’s comfortable for someone, or they have circulation issues, or this, or that, or the other.

Pacing = agitated… Except when it’s just someone who finds the body in motion more comfortable

Relaxed arms and hands = at ease and unthreatening… Unless it’s a practitioner of various martial arts for whom that is their default ready-for-action state.

Folded arms = closed-off, cold, distant… Or it was just somewhere to put one’s hands.

Lack of eye contact = deceitful, hiding something… Unless it’s actually for any one of a wide number of reasons, which brings us to our next section:

A liar’s “tells”

Again, if you know someone intimately and know what signs are associated with deceit in them, then great, that’s a thing you know. But for people in general…

A lot of what is repeated about “how to know if someone is lying” has seeped into public consciousness from “what police use to justify their belief that someone is lying”.

This is why many of the traditional “this person is lying” signs are based around behaviors that show up when in fact “this person is afraid, under pressure, and talking to an authority figure who has the power to ruin their life”:

Research on Non-verbal Signs of Lies and Deceit: A Blind Alley

But what about eye-accessing cues? They have science to them, right?

For any unfamiliar: this is about the theory that when we are accessing different parts of our mind (such as memory or creativity, thus truthfulness or lying), our eyes move one way or another according to what faculty we’re accessing.

Does it work? No

But, if you carefully calibrate it for a specific person, such as by asking them questions along the lines of “describe your front door” or “describe your ideal holiday”, to see which ways they look for recall or creativity… Then also no:

The Eyes Don’t Have It: Lie Detection and Neuro-Linguistic Programming

How can we know what non-verbal communication means, then?

With strangers? We can’t, simply. It’s on us to be open-minded, with a healthy balance of optimism and wariness.

With people we know? We can build up a picture over time, learn the person’s patterns. Best of all, we can ask them. In the moment, and in general.

For more on optimizing interpersonal communication, check out:

Save Time With Better Communication

…and the flipside of that:

The Problem With Active Listening (And How To Do It Better)

Take care!

Share This Post

-

28-Day FAST Start Day-by-Day – by Gin Stephens

10almonds is reader-supported. We may, at no cost to you, receive a portion of sales if you purchase a product through a link in this article.

We have previously reviewed Gin Stephens’ other book, “Fast. Feast. Repeat.”, so what’s so special about this one that it deserves reviewing too?

This one is all about troubleshooting the pitfalls that many people find when taking up intermittent fasting.

To be clear: the goal here is not a “28 days and yay you did it, put that behind you now”, but rather “28 days and you are now intermittently fasting easily each day and can keep it up without difficulty”. As for the difficulties that may arise early in the 28 days…

Not just issues of willpower, but also the accidental breaks. For example, some artificial sweeteners, while zero-calorie, trigger an insulin response, which breaks the fast on the metabolic level (avoiding that is the whole point of IF). Lots of little tips like that peppered through the book help the reader to stop accidentally self-sabotaging their progress.

The author does talk about psychological issues too, and also how it will feel different at first while the liver is adapting, than later when it has already depleted its glycogen reserves and the body must burn body fat instead. Information like that makes it easier to understand that some initial problems (hunger, getting “hangry”, feeling twitchy, or feeling light-headed) will last only a few weeks and then disappear.

So, understanding things like that makes a big difference too.

The style of the book is simple and clear pop-science, with lots of charts and bullet points and callout-boxes and the like; it makes for very easy reading, and very quick learning of all the salient points, of which there are many.

Bottom line: if you’ve tried intermittent fasting but struggled to make it stick, this book can help you get to where you want to be.

Share This Post

Related Posts

-

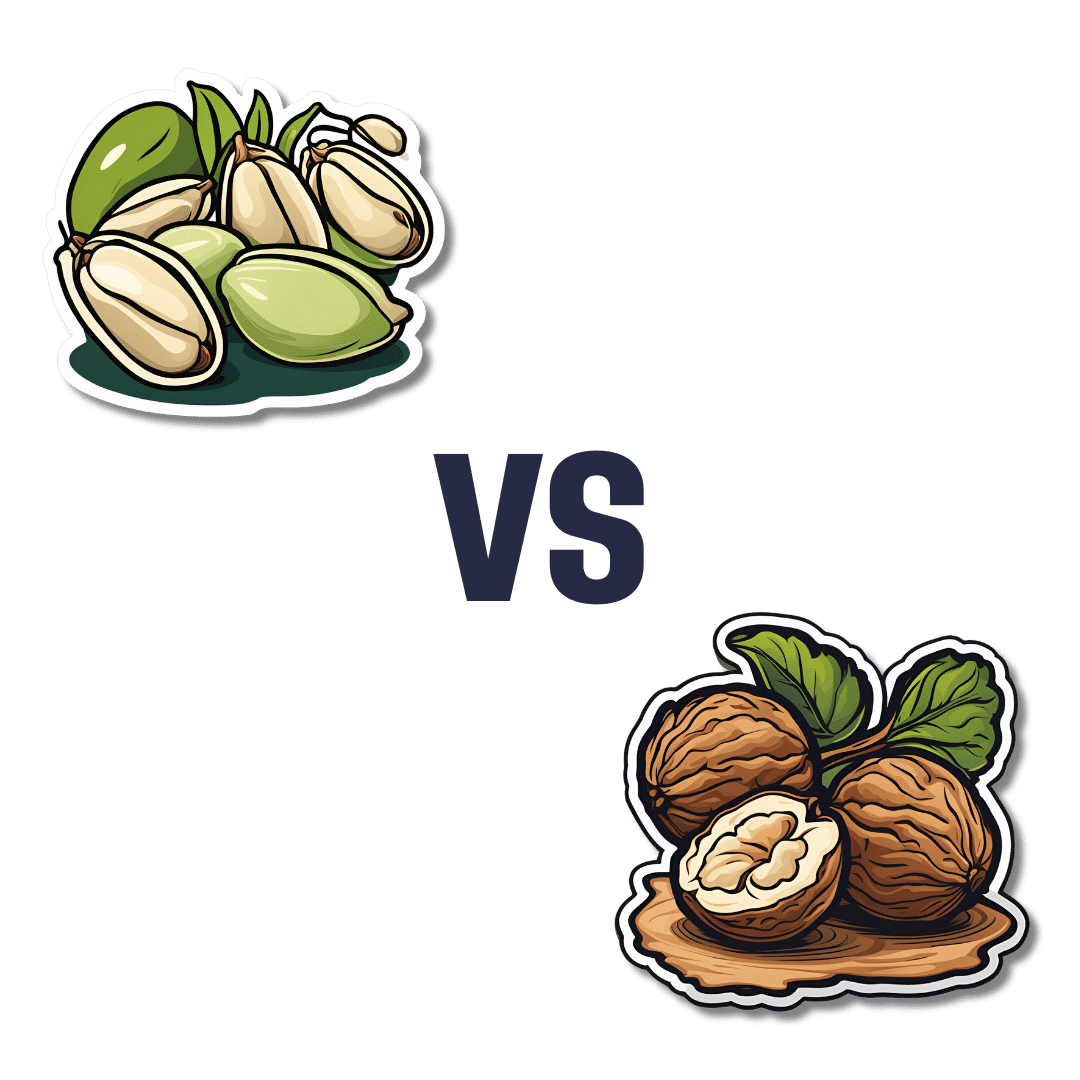

Pistachios vs Walnuts – Which is Healthier?

10almonds is reader-supported. We may, at no cost to you, receive a portion of sales if you purchase a product through a link in this article.

Our Verdict

When comparing pistachios to walnuts, we picked the pistachios.

Why?

Pistachios have more protein and fiber, while walnuts have more fat (though the fats are famously healthy, the same is true of the fats in pistachios).

In the category of vitamins, pistachios have several times more* of vitamins A, B1, B6, C, and E, while walnuts boast only a little more of vitamin B9. They are approximately equal on other vitamins they both contain.

*actually 25x more vitamin A, but the others are 2x, 3x, 4x more.

When it comes to minerals, things are more even; pistachios have more iron, phosphorus, potassium, and selenium, while walnuts have more copper, magnesium, manganese, and zinc. So this category’s a tie.

So given two clear wins for pistachios, and one tie, it’s evident that pistachios win the day.

However! Do enjoy both of these nuts; we often mention that diversity is good in general, and in this case, it’s especially true because of the different mineral profiles, and also because in terms of the healthy fats that they offer, pistachios offer more monounsaturated fats and walnuts offer more polyunsaturated fats; both are healthy, just different.

They’re about equal on saturated fat, in case you were wondering, as it makes up about 6% of the total fats in both cases.

Want to learn more?

You might like to read:

Why You Should Diversify Your Nuts

Take care!

Don’t Forget…

Did you arrive here from our newsletter? Don’t forget to return to the email to continue learning!

Learn to Age Gracefully

Join the 98k+ American women taking control of their health & aging with our 100% free (and fun!) daily emails:

-

High Histamine Foods To Avoid (And Low Histamine Foods To Eat Instead)

10almonds is reader-supported. We may, at no cost to you, receive a portion of sales if you purchase a product through a link in this article.

Nour Zibdeh is an Integrative and Functional Dietician, and she helps people overcome food intolerances. Today, it’s about getting rid of the underdiagnosed condition that is histamine intolerance, by first eliminating the triggers, and then not getting stuck on the low-histamine diet

The recommendations

High histamine foods to avoid include:

- Alcohol (all types)

- Fermented foods—normally great for the gut, but bad in this case

- That includes most cheeses and yogurts

- Aged, cured, or otherwise preserved meat

- Some plants, e.g. tomato, spinach, eggplant, banana, avocado. Again, normally all great, but not in this case.

Low histamine foods to eat include:

- Fruits and vegetables not mentioned above

- Minimally processed meat and fish, either fresh from the butcher/fishmonger, or frozen (not from the chilled food section of the supermarket), and eaten the same day they were purchased or defrosted, because otherwise histamine builds up over time (and quite quickly)

- Grains, but she recommends skipping gluten, given the high likelihood of a comorbid gluten intolerance. So instead she recommends for example quinoa, oats, rice, buckwheat, millet, etc.

For more about these (and more examples), as well as how to then phase safely off the low histamine diet, enjoy:

Click Here If The Embedded Video Doesn’t Load Automatically!

Further reading

Food intolerances often gang up on a person (i.e., comorbidity is high), so you might also like to read about:

- Gluten: What’s The Truth?

- Fiber For FODMAP-Avoiders

- Foods For Managing Hypothyroidism (incl. Hashimoto’s)

- Crohn’s, Food Intolerances, & More

Take care!

Don’t Forget…

Did you arrive here from our newsletter? Don’t forget to return to the email to continue learning!

Learn to Age Gracefully

Join the 98k+ American women taking control of their health & aging with our 100% free (and fun!) daily emails:

-

The Doctor’s Kitchen – by Dr. Rupy Aujla

10almonds is reader-supported. We may, at no cost to you, receive a portion of sales if you purchase a product through a link in this article.

We’ve featured Dr. Aujla before as an expert-of-the-week, and now it’s time to review a book by him. What’s his deal, and what should you expect?

Dr. Aujla first outlines the case for food as medicine. Not just “eat nutritionally balanced meals”, but literally, “here are the medicinal properties of these plants”. Think of some of the herbs and spices we’ve featured in our Monday Research Reviews, and add in medicinal properties of cancer-fighting cruciferous vegetables, bananas with dopamine and dopamine precursors, berries full of polyphenols, hemp seeds that fight cognitive decline, and so forth.

Most of the book is given over to recipes. They’re plant-centric, but mostly not vegan. They’re consistent with the Mediterranean diet, but mostly Indian. They’re economically mindful (favoring cheap ingredients where reasonable) while giving a nod to where an extra dollar will elevate the meal. They don’t give calorie values etc—this is a feature not a bug, as Dr. Aujla is of the “positive dieting” camp that advocates for us to “count colors, not calories”. Which, we have to admit, makes for very stress-free cooking, too.

Dr. Aujla is himself an Indian Brit, by the way, which gives him two intersecting factors for having a taste for spices. If you don’t share that taste, just go easier on the pepper etc.

As for the medicinal properties we mentioned up top? Four pages of references at the back, for any who are curious to look up the science of them. We at 10almonds do love references!

Bottom line: if you like tasty food and you’re looking for a one-stop, well-rounded, food-as-medicine cookbook, this one is a top-tier choice.

Don’t Forget…

Did you arrive here from our newsletter? Don’t forget to return to the email to continue learning!

Learn to Age Gracefully

Join the 98k+ American women taking control of their health & aging with our 100% free (and fun!) daily emails: