Can You Get Addicted To MSG, Like With Sugar?

10almonds is reader-supported. We may, at no cost to you, receive a portion of sales if you purchase a product through a link in this article.

Have a question or a request? We love to hear from you!

In cases where we’ve already covered something, we might link to what we wrote before, but will always be happy to revisit any of our topics again in the future too—there’s always more to say!

As ever: if the question/request can be answered briefly, we’ll do it here in our Q&A Thursday edition. If not, we’ll make a main feature of it shortly afterwards!

So, no question/request too big or small 😎

❝Hello, I love your newsletter 🙂 Can I have a question? While browsing through your recepies, I realised many contained MSG. As someone based in Europe, I am not used to using MSG while cooking (of course I know that processed food bought in supermarket containes MSG). There is a stigma, that MSG is not particulary healthy, but rather it should be really bad and cause negative effects like headaches. Is this true? Also, can you get addicted to MSG, just like you get addicted to sugar? Thank you :)❞

Thank you for the kind words, and the interesting questions!

Short answer: no and no 🙂

Longer answer: most of the negative reputation about MSG comes from a single piece of satire written in the US in the 1960s, which the popular press then misrepresented as a genuine concern, and the public then ran with, mostly due to racism/xenophobia/sinophobia specifically, given the US’s historically not fabulous relations with China, and the moniker of “Chinese restaurant syndrome”, notwithstanding that MSG was first isolated in Japan, not China, more than 100 years ago.

The silver lining that comes out of this is that because of the above, MSG has been one of the most-studied food additives in recent decades, with many teams of scientists in many countries trying to determine its risks and not finding any (except insofar as anything in extreme quantities can kill you, including water or oxygen).

You can read more about this and other* myths about MSG, here:

Monosodium Glutamate: Sinless Flavor-Enhancer Or Terrible Health Risk?

*such as pertaining to gluten sensitivity, which in reality MSG has no bearing on whatsoever as it does not contain gluten and is not even made of the same basic stuff; gluten being a protein made of (amongst other things) the amino acid glutamine, not a glutamate salt. Glutamate is as closely related to gluten as cyanocobalamin (vitamin B12) is to cyanide (the famous poison).

PS: if you didn’t click the above link to read that article, then 1) we really do recommend it 2) we did some LD50 calculations there and looked at available research, and found that for someone of this writer’s (very medium) size, eating 1kg of MSG at once is sufficient to cause toxicity, and injecting >250g of MSG may cause heart problems. So we don’t recommend doing that.

However, ½ tsp in a recipe that gives multiple portions is not going to get you anywhere close to the danger zone, unless you consume that entire meal by yourself hundreds of times per day. And if you do, the MSG is probably the least of your concerns.

(2 tsp of cassia cinnamon, however, is enough to cause coumarin toxicity; for this reason we recommend Ceylon (or “True” or “Sweet”) cinnamon in our recipes, as it has almost undetectable levels of coumarin)

With regard to your interesting question about addiction, first of all let’s speak briefly about sugar addiction:

Sugar addiction is, by broad scientific consensus, agreed-upon as an extant thing that does exist, and contemporary research is more looking into the “hows” and “whys” and “whats” rather than the “whether”. It is a somewhat complicated topic, because it’s halfway between what science would usually consider a chemical addiction, and what science would usually consider a behavioral addiction:

The Not-So-Sweet Science Of Sugar Addiction

The reasonable prevailing hypothesis, therefore, is that sugar simply has two moderate mechanisms of addiction, rather than one strong one.

The biochemical side of sugar addiction comes from the body’s metabolism of sugar, so this cannot be a thing for MSG, because there is nothing to metabolize in the same sense of the word (MSG being an inorganic compound with zero calories).

People can crave salt, especially when deficient in it, and MSG does contain sodium (it’s what the “S” stands for), but it contains a little under ⅓ of the sodium that table salt does (sodium chloride in whatever form, be it sea salt, rock salt, or such):

MSG vs. Salt: Sodium Comparison ← we do molecular calculations here!

Sea Salt vs MSG – Which is Healthier? ← this one for a head-to-head

However, even craving salt does not constitute an addiction; nobody is shamefully hiding their rock salt crystals under their bed and getting a fix when they feel low, and nor does withdrawal cause adverse side effects, except insofar as (once again) a person deficient in salt will crave salt.

Finally, the only other way we know of that one might wonder if MSG could be addictive, is about glutamate and glutamate receptors. The glutamate in MSG is the same glutamate (down to the atoms) as the glutamate formed if one consumes tomatoes in the presence of salt, and triggers the same glutamate receptors in the same way. We have the same number of receptors either way, and uptake is exactly the same (because again, it’s exactly the same chemical) so there is a maximum to how strong this effect can be, and that maximum is the same whatever the source of the glutamate was.

In this respect, if MSG is addictive, then so is a tomato salad with a pinch of salt: it’s not—it’s just tasty.

We haven’t cited papers in today’s article, but it’s just because we cited them already in the articles we linked, and so we avoided doubling up. Most of them are in that first link we gave 🙂

One final note

Technically anyone can develop a sensitivity to anything, so in theory someone could develop a sensitivity to MSG, just like they could for any other ingredient. Our usual legal/medical disclaimer applies.

However, it’s certainly not a common trigger, putting it well below common allergens like nuts (or less common allergens like, say, bananas), not even in the same league as common intolerances such as gluten, and less worthy of health risk warnings than, say, spinach (high in oxalates; fine for most people but best avoided if you have kidney problems).

The reason we use it in the recipes we use it in, is simply because it’s a lower-sodium alternative to salt, and while it contains a (very) tiny bit less sodium than low-sodium salt (which itself has about ⅓ the sodium of regular salt), it has more of a flavor-enhancing effect, such that one can use half as much, for a more than sixfold total sodium reduction. Which for most of us in the industrialized world, is beneficial.

Want to try some?

If today’s article has inspired you to give MSG a try, here’s an example product on Amazon 😎

Enjoy!

Don’t Forget…

Did you arrive here from our newsletter? Don’t forget to return to the email to continue learning!

Recommended

Learn to Age Gracefully

Join the 98k+ American women taking control of their health & aging with our 100% free (and fun!) daily emails:

-

Power Plates – by Gena Hamshaw

10almonds is reader-supported. We may, at no cost to you, receive a portion of sales if you purchase a product through a link in this article.

Superfoods are all well and good, but there are only so many ways one can reasonably include watercress before it starts becoming a chore.

Happily, Gena Hamshaw is here with a hundred single-dish vegan meals, that are not only nutritionally balanced as the subtitle promises, but also, as the title suggests, are nutritional powerhouses too.

In the category of criticism, some ingredients are not so universally available as others. For example, depending on where you live, your local supermarket might not have freekeh, gochujang, or pomegranate molasses.

However, most of the recipes have ingredients that are easy enough to source in any medium-sized supermarket, and for the ones that aren’t, we do recommend ordering the ingredient online and trying something you might not otherwise have experienced—that’s an important thing in life, after all!

Bottom line: if you’d like plant-based meals that are packed full of nutrients and are delicious too, this is a top-tier recipe book.

Click here to check out Power Plates, and enjoy a wide variety of plant-based cuisine!

Share This Post

-

Quit Drinking – by Rebecca Dolton

10almonds is reader-supported. We may, at no cost to you, receive a portion of sales if you purchase a product through a link in this article.

Many “quit drinking” books focus on tips you’ve heard already—cut down like this, rearrange your habits like that, make yourself accountable like so, add a reward element this way, etc.

Dolton takes a different approach.

She focuses instead on the underlying processes of addiction, so as to not merely understand them to fight them, but also to use them against the addiction itself.

This is not just a social or behavioral analysis, by the way, and goes into some detail into the physiological factors of the addiction—including such things as the little-talked about relationship between addiction and gut flora. Candida albans, found in most if not all humans to some extent, gets really out of control when given certain kinds of sugars (including those from alcohol); it grows, eventually puts roots through the intestinal walls (ouch!) and the more it grows, the more it demands the sugars it craves, so the more you feed it.

Quite a motivator to not listen to such cravings! It’s not even you that wants it, it’s the Candida!

Anyway, that’s just one example; there are many. The point here is that this is a well-researched, well-written book that sets itself apart from many of its genre.

Share This Post

-

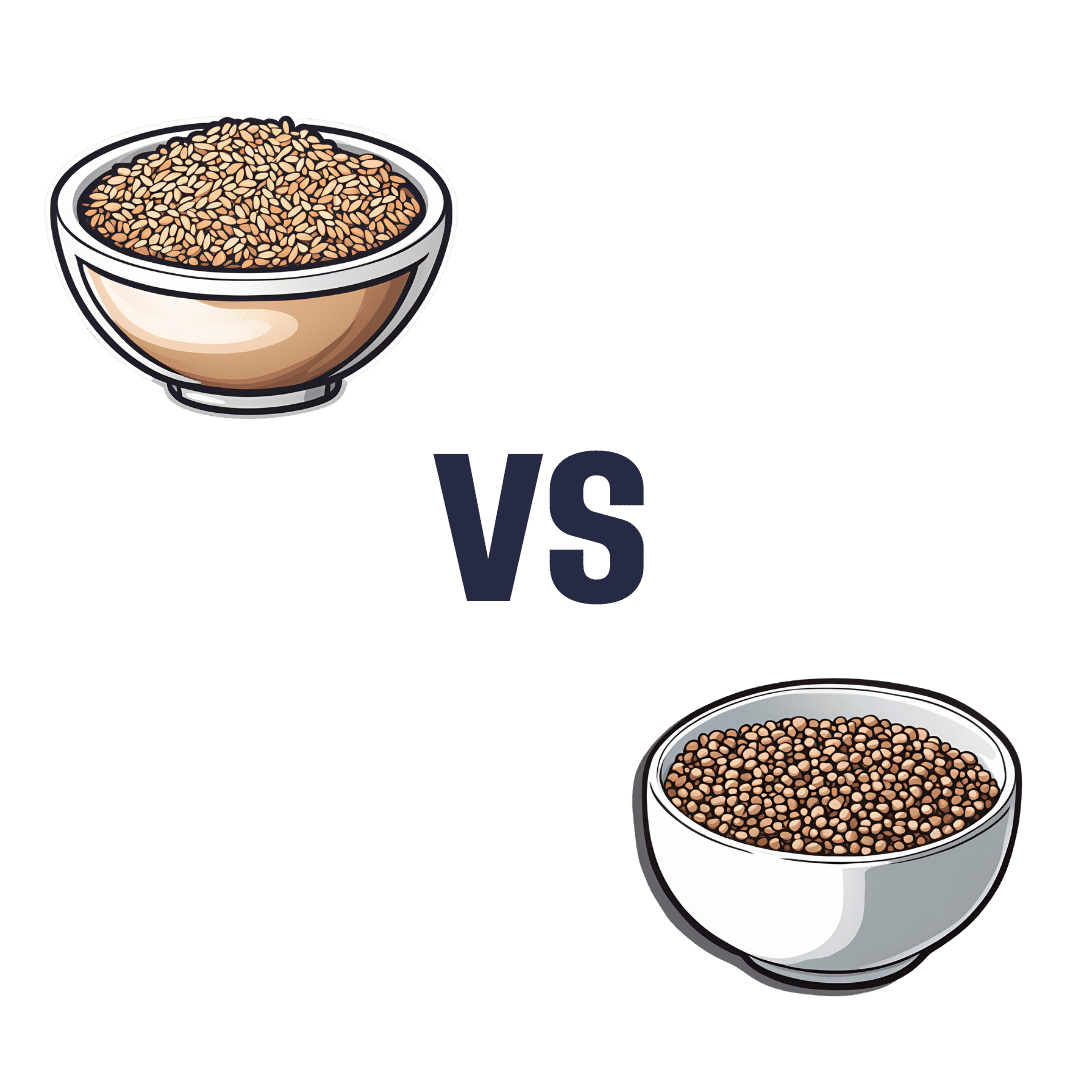

Brown Rice vs Buckwheat – Which is Healthier?

10almonds is reader-supported. We may, at no cost to you, receive a portion of sales if you purchase a product through a link in this article.

Our Verdict

When comparing brown rice to buckwheat, we picked the buckwheat.

Why?

In terms of macros, brown rice has more carbs, while buckwheat has nearly 2x the fiber, and more protein. An easy choice here: buckwheat for the win.

In the category of vitamins, brown rice has more of vitamins B1, B2, B3, B6, and E, while buckwheat has more of vitamins B9, K, and choline. A win for brown rice this time, although as a point in buckwheat’s favor, while most of the margins of difference are comparable, buckwheat has nearly 10x the vitamin K.

When it comes to minerals, brown rice has more manganese, phosphorus, selenium, and zinc, while buckwheat has more calcium, copper, iron, and magnesium. A win for buckwheat again this time.

A quick note on gluten: both of these are naturally gluten-free, so that’s not an issue here. Buckwheat, despite its name, is not a wheat, nor even closely related to wheat. It’s not even technically a grain; it’s a flowering plant of which we eat the groats. In taxonomic terms, buckwheat is about as related to wheat as a lionfish is to a lion.

Adding up the sections makes for an overall 2:1 win for buckwheat, though even if it weren’t for that, which is someone more likely to hear from a doctor, “you need to eat more fiber”, or “you need to eat more vitamin E”? Thus, even had the categories been tied (let’s imagine it had been tied on minerals, say) that’d have been a tiebreaker in favor of buckwheat. As it is, buckwheat already won by strength of numbers anyway.

Of course, do enjoy either or both; diversity is good!

Want to learn more?

You might like to read:

Grains: Bread Of Life, Or Cereal Killer?

Enjoy!

Share This Post

Related Posts

-

The Many Faces Of Cosmetic Surgery

10almonds is reader-supported. We may, at no cost to you, receive a portion of sales if you purchase a product through a link in this article.

Cosmetic Surgery: What’s The Truth?

In Tuesday’s newsletter, we asked you your opinion on elective cosmetic surgeries, and got the above-depicted, below-described, set of responses:

- About 48% said “Everyone should be able to get what they want, assuming informed consent”

- About 28% said “It can ease discomfort to bring features more in line with normalcy”

- 15% said “They should be available in the case of extreme disfigurement only”

- 10% said “No elective cosmetic surgery should ever be performed; needless danger”

Well, there was a clear gradient of responses there! Not so polarizing as we might have expected, but still enough dissent for discussion

So what does the science say?

The risks of cosmetic surgery outweigh the benefits: True or False?

False, subjectively (but this is important).

You may be wondering: how is science subjective?

And the answer is: the science is not subjective, but people’s cost:worth calculations are. What’s worth it to one person absolutely may not be worth it to another. Which means: for those for whom it wouldn’t be worth it, they are usually the people who will not choose the elective surgery.

Let’s look at some numbers (specifically, regret rates for various surgeries, elective/cosmetic or otherwise):

- Regret rate for elective cosmetic surgery in general: 20%

- Regret rate for knee replacement (i.e., not cosmetic): 17.1%

- Regret rate for hip replacement (i.e., not cosmetic): 4.8%

- Regret rate for gender-affirming surgeries (for transgender patients): 1%

So we can see, elective surgeries have an 80–99% satisfaction rate, depending on what they are. In comparison, the two joint replacements we mentioned have a 82.9–95.2% satisfaction rate. Not too dissimilar, taken in aggregate!

In other words: if a person has studied the risks and benefits of a surgery and decides to go ahead, they’re probably going to be happy with the results, and for them, the benefits will have outweighed the risks.

Sources for the above numbers, by the way:

- What is the regret rate for plastic surgery?

- Decision regret after primary hip and knee replacement surgery

- A systematic review of patient regret after surgery—a common phenomenon in many specialties but rare within gender-affirmation surgery

But it’s just a vanity; therapy is what’s needed instead: True or False?

False, generally. True, sometimes. Whatever the reasons for why someone feels the way they do about their appearance—whether their face got burned in a fire or they just have triple-J cups that they’d like reduced, it’s generally something they’ve already done a lot of thinking about. Nevertheless, it does also sometimes happen that it’s a case of someone hoping it’ll be the magical solution, when in reality something else is also needed.

How to know the difference? One factor is whether the surgery is “type change” or “restorative”, and both have their pros and cons.

- In “type change” (e.g. rhinoplasty), more psychological adjustment is needed, but when it’s all over, the person has a new nose and, statistically speaking, is usually happy with it.

- In “restorative” (e.g. facelift), less psychological adjustment is needed (as it’s just a return to a previous state), so a person will usually be happy quickly, but ultimately it is merely “kicking the can down the road” if the underlying problem is “fear of aging”, for example. In such a case, likely talking therapy would be beneficial—whether in place of, or alongside, cosmetic surgery.

Here’s an interesting paper on that; the sample sizes are small, but the discussion about the ideas at hand is a worthwhile read:

Does cosmetic surgery improve psychosocial wellbeing?

Some people will never be happy no matter how many surgeries they get: True or False?

True! We’re going to refer to the above paper again for this one. In particular, here’s what it said about one group for whom surgeries will not usually be helpful:

❝There is a particular subgroup of people who appear to respond poorly to cosmetic procedures. These are people with the psychiatric disorder known as “body dysmorphic disorder” (BDD). BDD is characterised by a preoccupation with an objectively absent or minimal deformity that causes clinically significant distress or impairment in social, occupational, or other areas of functioning.

For several reasons, it is important to recognise BDD in cosmetic surgery settings:

Firstly, it appears that cosmetic procedures are rarely beneficial for these people. Most patients with BDD who have had a cosmetic procedure report that it was unsatisfactory and did not diminish concerns about their appearance.

Secondly, BDD is a treatable disorder. Serotonin-reuptake inhibitors and cognitive behaviour therapy have been shown to be effective in about two-thirds of patients with BDD❞

~ Dr. David Castle et al. (lightly edited for brevity)

Which is a big difference compared to, for example, someone having triple-J breasts that need reducing, or the wrong genitals for their gender, or a face whose features are distinct outliers.

Whether that’s a reason people with BDD shouldn’t be able to get it is an ethical question rather than a scientific one, so we’ll not try to address that with science.

After all, many people (in general) will try to fix their woes with a haircut, a tattoo, or even a new sportscar, and those might sometimes be bad decisions, but they are still the person’s decision to make.

And even so, there can be protectionist laws/regulations that may provide a speed-bump, for example:

Take care!

Don’t Forget…

Did you arrive here from our newsletter? Don’t forget to return to the email to continue learning!

Learn to Age Gracefully

Join the 98k+ American women taking control of their health & aging with our 100% free (and fun!) daily emails:

-

Do We Simply Not Care About Old People?

10almonds is reader-supported. We may, at no cost to you, receive a portion of sales if you purchase a product through a link in this article.

The covid-19 pandemic would be a wake-up call for America, advocates for the elderly predicted: incontrovertible proof that the nation wasn’t doing enough to care for vulnerable older adults.

The death toll was shocking, as were reports of chaos in nursing homes and seniors suffering from isolation, depression, untreated illness, and neglect. Around 900,000 older adults have died of covid-19 to date, accounting for 3 of every 4 Americans who have perished in the pandemic.

But decisive actions that advocates had hoped for haven’t materialized. Today, most people — and government officials — appear to accept covid as a part of ordinary life. Many seniors at high risk aren’t getting antiviral therapies for covid, and most older adults in nursing homes aren’t getting updated vaccines. Efforts to strengthen care quality in nursing homes and assisted living centers have stalled amid debate over costs and the availability of staff. And only a small percentage of people are masking or taking other precautions in public despite a new wave of covid, flu, and respiratory syncytial virus infections hospitalizing and killing seniors.

In the last week of 2023 and the first two weeks of 2024 alone, 4,810 people 65 and older lost their lives to covid — a group that would fill more than 10 large airliners — according to data provided by the CDC. But the alarm that would attend plane crashes is notably absent. (During the same period, the flu killed an additional 1,201 seniors, and RSV killed 126.)

“It boggles my mind that there isn’t more outrage,” said Alice Bonner, 66, senior adviser for aging at the Institute for Healthcare Improvement. “I’m at the point where I want to say, ‘What the heck? Why aren’t people responding and doing more for older adults?’”

It’s a good question. Do we simply not care?

I put this big-picture question, which rarely gets asked amid debates over budgets and policies, to health care professionals, researchers, and policymakers who are older themselves and have spent many years working in the aging field. Here are some of their responses.

The pandemic made things worse. Prejudice against older adults is nothing new, but “it feels more intense, more hostile” now than previously, said Karl Pillemer, 69, a professor of psychology and gerontology at Cornell University.

“I think the pandemic helped reinforce images of older people as sick, frail, and isolated — as people who aren’t like the rest of us,” he said. “And human nature being what it is, we tend to like people who are similar to us and be less well disposed to ‘the others.’”

“A lot of us felt isolated and threatened during the pandemic. It made us sit there and think, ‘What I really care about is protecting myself, my wife, my brother, my kids, and screw everybody else,’” said W. Andrew Achenbaum, 76, the author of nine books on aging and a professor emeritus at Texas Medical Center in Houston.

In an environment of “us against them,” where everybody wants to blame somebody, Achenbaum continued, “who’s expendable? Older people who aren’t seen as productive, who consume resources believed to be in short supply. It’s really hard to give old people their due when you’re terrified about your own existence.”

Although covid continues to circulate, disproportionately affecting older adults, “people now think the crisis is over, and we have a deep desire to return to normal,” said Edwin Walker, 67, who leads the Administration on Aging at the Department of Health and Human Services. He spoke as an individual, not a government representative.

The upshot is “we didn’t learn the lessons we should have,” and the ageism that surfaced during the pandemic hasn’t abated, he observed.

Ageism is pervasive. “Everyone loves their own parents. But as a society, we don’t value older adults or the people who care for them,” said Robert Kramer, 74, co-founder and strategic adviser at the National Investment Center for Seniors Housing & Care.

Kramer thinks boomers are reaping what they have sown. “We have chased youth and glorified youth. When you spend billions of dollars trying to stay young, look young, act young, you build in an automatic fear and prejudice of the opposite.”

Combine the fear of diminishment, decline, and death that can accompany growing older with the trauma and fear that arose during the pandemic, and “I think covid has pushed us back in whatever progress we were making in addressing the needs of our rapidly aging society. It has further stigmatized aging,” said John Rowe, 79, professor of health policy and aging at Columbia University’s Mailman School of Public Health.

“The message to older adults is: ‘Your time has passed, give up your seat at the table, stop consuming resources, fall in line,’” said Anne Montgomery, 65, a health policy expert at the National Committee to Preserve Social Security and Medicare. She believes, however, that baby boomers can “rewrite and flip that script if we want to and if we work to change systems that embody the values of a deeply ageist society.”

Integration, not separation, is needed. The best way to overcome stigma is “to get to know the people you are stigmatizing,” said G. Allen Power, 70, a geriatrician and the chair in aging and dementia innovation at the Schlegel-University of Waterloo Research Institute for Aging in Canada. “But we separate ourselves from older people so we don’t have to think about our own aging and our own mortality.”

The solution: “We have to find ways to better integrate older adults in the community as opposed to moving them to campuses where they are apart from the rest of us,” Power said. “We need to stop seeing older people only through the lens of what services they might need and think instead of all they have to offer society.”

That point is a core precept of the National Academy of Medicine’s 2022 report Global Roadmap for Healthy Longevity. Older people are a “natural resource” who “make substantial contributions to their families and communities,” the report’s authors write in introducing their findings.

Those contributions include financial support to families, caregiving assistance, volunteering, and ongoing participation in the workforce, among other things.

“When older people thrive, all people thrive,” the report concludes.

Future generations will get their turn. That’s a message Kramer conveys in classes he teaches at the University of Southern California, Cornell, and other institutions. “You have far more at stake in changing the way we approach aging than I do,” he tells his students. “You are far more likely, statistically, to live past 100 than I am. If you don’t change society’s attitudes about aging, you will be condemned to lead the last third of your life in social, economic, and cultural irrelevance.”

As for himself and the baby boom generation, Kramer thinks it’s “too late” to effect the meaningful changes he hopes the future will bring.

“I suspect things for people in my generation could get a lot worse in the years ahead,” Pillemer said. “People are greatly underestimating what the cost of caring for the older population is going to be over the next 10 to 20 years, and I think that’s going to cause increased conflict.”

KFF Health News is a national newsroom that produces in-depth journalism about health issues and is one of the core operating programs at KFF—an independent source of health policy research, polling, and journalism. Learn more about KFF.

USE OUR CONTENT

This story can be republished for free (details).

KFF Health News is a national newsroom that produces in-depth journalism about health issues and is one of the core operating programs at KFF—an independent source of health policy research, polling, and journalism. Learn more about KFF.

Subscribe to KFF Health News’ free Morning Briefing.

Don’t Forget…

Did you arrive here from our newsletter? Don’t forget to return to the email to continue learning!

Learn to Age Gracefully

Join the 98k+ American women taking control of their health & aging with our 100% free (and fun!) daily emails:

-

When Doctors Make House Calls, Modern-Style!

10almonds is reader-supported. We may, at no cost to you, receive a portion of sales if you purchase a product through a link in this article.

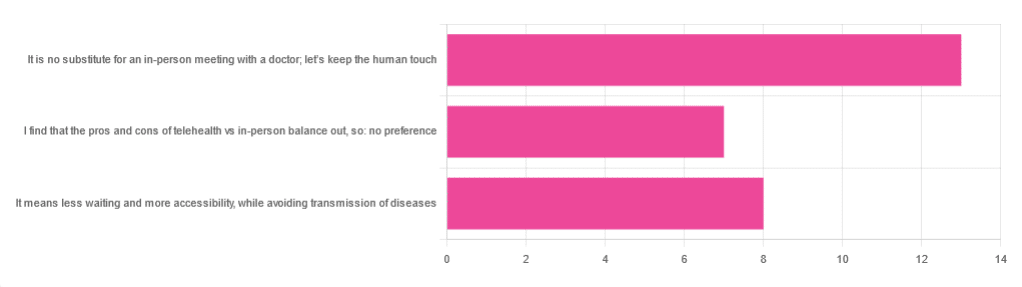

In Tuesday’s newsletter, we asked you foryour opinion of telehealth for primary care consultations*, and got the above-depicted, below-described, set of responses:

- About 46% said “It is no substitute for an in-person meeting with a doctor; let’s keep the human touch”

- About 29% said “It means less waiting and more accessibility, while avoiding transmission of diseases”

- And 25 % said “I find that the pros and cons of telehealth vs in-person balance out, so: no preference”

*We specified that by “primary care” we mean the initial consultation with a non-specialist doctor, before receiving treatment or being referred to a specialist. By “telehealth” we mean by videocall or phonecall.

So, what does the science say?

A quick note first

Because telehealth was barely a thing (statistically speaking) before the first stages of the COVID pandemic, compared to how it is now, most of the science for this is young, and a lot of the science simply hasn’t been done yet, and/or has not been published yet, because the process can take years.

Because of this, some studies we do have aren’t specifically about primary care, and are sometimes about specialists. We think this should not affect the results much, but it bears highlighting.

Nevertheless, we’ll do what we can with the science we have!

Telehealth is more accessible than in-person consultations: True or False?

True, for most people. For example…

❝Data was found from a variety of emergency and non-emergency departments of primary, secondary, and specialised healthcare.

Satisfaction was high among recipients of healthcare, scoring 9-10 on a scale of 0-10 or ranging from 73.3% to 100%.

Convenience was rated high in every specialty examined. Satisfaction of clinicians was high throughout the specialities despite connection failure and concerns about confidentiality of information.❞

whereas…

❝Nonetheless, studies reported perception of increased barriers to accessing care and inequalities for vulnerable patients especially in older people❞

~ Ibid.

Source: Satisfaction with telemedicine use during COVID-19 pandemic in the UK: a systematic review

Now, perception of those things does necessarily equate to an actual increased barrier, but it is reasonable that someone who thinks something is inaccessible will be less inclined to try to access it.

The quality of care provided via telehealth is as good as in-person: True or False?

True, ostensibly, with caveats. The caveats are:

- We’re going offreported patient satisfaction, not objective patient health outcomes (we found little* science as yet for the relative incidence of misdiagnosis, for example—which kind of thing will take time to be revealed).

- We’re also therefore speaking (as statistics do) for the significant majority of people. However, if we happen to be (statistically speaking) an insignificant minority, well, that just sucks for us personally.

*we did find some, but it wasn’t very helpful yet. For example:

An electronic trigger to detect telemedicine-related diagnostic errors

this one does look at the incidence of diagnostic errors, but provides no control group (i.e. otherwise-comparable in-person consultations) for comparison.

While most oft-considered demographic groups reported comparable patient satisfaction (per race, gender, and socioeconomic status, for example), there was one outlier variable, which was age (as we quoted from that first study above).

However!

Looking under the hood of these stats, it seems that age is not the real culprit, so much as technological illiteracy, which is heavily correlated with age:

❝Lower eHealth literacy is associated with more negative attitudes towards I/C technology in healthcare. This trend is consistent across diverse demographics and regions. ❞

Source: Meta-analysis: eHealth literacy and attitudes towards internet/computer technology

There are things that can be done at an in-person consultation that can’t be done by telehealth: True or False?

True, of course. It is incredibly rare that we will cite “common sense”, (as sometimes “common sense” is actually “common mistakes” and is simply and verifiably wrong), but in this case, as one 10almonds subscriber put it:

❝The doctor uses his five senses to assess. This cannot be attained over the phone❞

~ 10almonds subscriber

A quick note first: if your doctor is using their sense of taste to diagnose you, please get a different doctor, because they should definitely not be doing that!

Not in this century, anyway… Once upon a time, diabetes was diagnosed by urine-tasting (and yes, that was a fairly reliable method).

However, nowadays indeed a doctor will use sight, sound, touch, and sometimes even smell.

In a videocall we’re down to two of those senses (sight and sound), and in a phonecall, down to one (sound) and even that is hampered. Your doctor cannot, for example, use a stethoscope over the phone.

With this in mind, it really comes down to what you need from your doctor in that consultation.

- If you’re 99% sure that what you need is to be prescribed an antidepressant, that probably doesn’t need a full physical.

- If you’re 99% sure that what you need is a referral, chances are that’ll be fine by telehealth too.

- If your doctor is 99% sure that what you need is a verbal check-up (e.g. “How’s it been going for you, with the medication that I prescribed for you a month ago?”, then again, a call is probably fine.

If you have a worrying lump, or an unhappy bodily discharge, or an unexplained mysterious pain? These things, more likely an in-person check-up is in order.

Take care!

Don’t Forget…

Did you arrive here from our newsletter? Don’t forget to return to the email to continue learning!

Learn to Age Gracefully

Join the 98k+ American women taking control of their health & aging with our 100% free (and fun!) daily emails: