Hope: A research-based explainer

10almonds is reader-supported. We may, at no cost to you, receive a portion of sales if you purchase a product through a link in this article.

This year, more than 60 countries, representing more than 4 billion people, will hold major elections. News headlines already are reporting that voters are hanging on to hope. When things get tough or don’t go our way, we’re told to hang on to hope. HOPE was the only word printed on President Barack Obama’s iconic campaign poster in 2008.

Research on hope has flourished only in recent decades. There’s now a growing recognition that hope has a role in physical, social, and mental health outcomes, including promoting resilience. As we embark on a challenging year of news, it’s important for journalists to learn about hope.

So what is hope? And what does the research say about it?

Merriam-Webster defines hope as a “desire accompanied by expectation of or belief in fulfillment.” This definition highlights the two basic dimensions of hope: a desire and a belief in the possibility of attaining that desire.

Hope is not Pollyannaish optimism, writes psychologist Everett Worthington in a 2020 article for The Conversation. “Instead, hope is a motivation to persevere toward a goal or end state, even if we’re skeptical that a positive outcome is likely.”

There are several scientific theories about hope.

One of the first, and most well-known, theories on hope was introduced in 1991 by American psychologist Charles R. Snyder.

In a paper published in the Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, Snyder defined hope as a cognitive trait centered on the pursuit of goals and built on two components: a sense of agency in achieving a goal, and a perceived ability to create pathways to achieve that goal. He defined hope as something individualistic.

Snyder also introduced the Hope Scale, which continues to be used today, as a way to measure hope. He suggested that some people have higher levels of hope than others and there seem to be benefits to being more hopeful.

“For example, we would expect that higher as compared with lower hope people are more likely to have a healthy lifestyle, to avoid life crises, and to cope better with stressors when they are encountered,” they write.

Others have suggested broader definitions.

In 1992, Kaye Herth, a professor of nursing and a scholar on hope, defined hope as “a multidimensional dynamic life force characterized by a confident yet uncertain expectation of achieving good, which to the hoping person, is realistically possible and personally significant.” Herth also developed the Herth Hope Index, which is used in various settings, including clinical practice and research.

More recently, others have offered an even broader definition of hope.

Anthony Scioli, a clinical psychologist and author of several books on hope, defines hope “as an emotion with spiritual dimensions,” in a 2023 review published in Current Opinion in Psychology. “Hope is best viewed as an ameliorating emotion, designed to fill the liminal space between need and reality.”

Hope is also nuanced.

“Our hopes may be active or passive, patient or critical, private or collective, grounded in the evidence or resolute in spite of it, socially conservative or socially transformative,” writes Darren Webb in a 2007 study published in History of the Human Sciences. “We all hope, but we experience this most human of all mental feelings in a variety of modes.”

To be sure, a few studies have shown that hope can have negative outcomes in certain populations and situations. For example, one study highlighted in the research roundup below finds that Black college students who had higher levels of hope experienced more stress due to racial discrimination compared with Black students who had lower levels of hope.

Today, hope is one of the most well-studied constructs within the field of positive psychology, according to the journal Current Opinion in Psychology, which dedicated its August 2023 issue to the subject. (Positive psychology is a branch of psychology focused on characters and behaviors that allow people to flourish.)

We’ve gathered several studies below to help you think more deeply about hope and recognize its role in your everyday lives.

Research roundup

The Role of Hope in Subsequent Health and Well-Being For Older Adults: An Outcome-Wide Longitudinal Approach

Katelyn N.G. Long, et al. Global Epidemiology, November 2020.

The study: To explore the potential public health implications of hope, researchers examine the relationship between hope and physical, behavioral and psychosocial outcomes in 12,998 older adults in the U.S. with a mean age of 66.

Researchers note that most investigations on hope have focused on psychological and social well-being outcomes and less attention has been paid to its impact on physical and behavioral health, particularly among older adults.

The findings: Results show a positive association between an increased sense of hope and a variety of behavioral and psychosocial outcomes, such as fewer sleep problems, more physical activity, optimism and satisfaction with life. However, there wasn’t a clear association between hope and all physical health outcomes. For instance, hope was associated with a reduced number of chronic conditions, but not with stroke, diabetes and hypertension.

The takeaway: “The later stages of life are often defined by loss: the loss of health, loved ones, social support networks, independence, and (eventually) loss of life itself,” the authors write. “Our results suggest that standard public health promotion activities, which often focus solely on physical health, might be expanded to include a wider range of factors that may lead to gains in hope. For example, alongside community-based health and nutrition programs aimed at reducing chronic conditions like hypertension, programs that help strengthen marital relations (e.g., closeness with a spouse), provide opportunities to volunteer, help lower anxiety, or increase connection with friends may potentially increase levels of hope, which in turn, may improve levels of health and well-being in a variety of domains.”

Associated Factors of Hope in Cancer Patients During Treatment: A Systematic Literature Review

Corine Nierop-van Baalen, Maria Grypdonck, Ann van Hecke and Sofie Verhaeghe. Journal of Advanced Nursing, March 2020.

The study: The authors review 33 studies, written in English or Dutch and published in the past decade, on the relationship between hope and the quality of life and well-being of patients with cancer. Studies have shown that many cancer patients respond to their diagnosis by nurturing hope, while many health professionals feel uneasy when patients’ hopes go far beyond their prognosis, the authors write.

The findings: Quality of life, social support and spiritual well-being were positively associated with hope, as measured with various scales. Whereas symptoms, psychological distress and depression had a negative association with hope. Hope didn’t seem to be affected by the type or stage of cancer or the patient’s demographics.

The takeaway: “Hope seems to be a process that is determined by a person’s inner being rather than influenced from the outside,” the authors write. “These factors are typically given meaning by the patients themselves. Social support, for example, is not about how many patients experience support, but that this support has real meaning for them.”

Characterizing Hope: An Interdisciplinary Overview of the Characteristics of Hope

Emma Pleeging, Job van Exel and Martijn Burger. Applied Research in Quality of Life, September 2021.

The study: This systematic review provides an overview of the concept of hope based on 66 academic papers in ten academic fields, including economics and business studies, environmental studies, health studies, history, humanities, philosophy, political science, psychology, social science, theology and youth studies, resulting in seven themes and 41 sub-themes.

The findings: The authors boil down their findings to seven components: internal and external sources, the individual and social experience of hope, internal and external effects, and the object of hope, which can be “just about anything we can imagine,” the authors write.

The takeaway: “An important implication of these results lies in the way hope is measured in applied and scientific research,” researchers write. “When measuring hope or developing instruments to measure it, researchers could be well-advised to take note of the broader understanding of the topic, to prevent that important characteristics might be overlooked.”

Revisiting the Paradox of Hope: The Role of Discrimination Among First-Year Black College Students

Ryon C. McDermott, et al. Journal of Counseling Psychology, March 2020.

The study: Researchers examine the moderating effects of hope on the association between experiencing racial discrimination, stress and academic well-being among 203 first-year U.S. Black college students. They build on a small body of evidence that suggests high levels of hope might have a negative effect on Black college students who experience racial discrimination.

The authors use data gathered as part of an annual paper-and-pencil survey of first-year college students at a university on the Gulf Coast, which the study doesn’t identify.

The findings: Researchers find that Black students who had higher levels of hope experienced more stress due to racial discrimination compared with students who had lower levels of hope. On the other hand, Black students with low levels of hope may be less likely to experience stress when they encounter discrimination.

Meanwhile, Black students who had high levels of hope were more successful in academic integration — which researchers define as satisfaction with and integration into the academic aspects of college life — despite facing discrimination. But low levels of hope had a negative impact on students’ academic well-being.

“The present study found evidence that a core construct in positive psychology, hope, may not always protect Black students from experiencing the psychological sting of discrimination, but it was still beneficial to their academic well-being,” the authors write.

The takeaway: “Our findings also highlight an urgent need to reduce discrimination on college campuses,” the researchers write. “Reducing discrimination could help Black students (and other racial minorities) avoid additional stress, as well as help them realize the full psychological and academic benefits of having high levels of hope.”

Additional reading

Hope Across Cultural Groups Lisa M. Edwards and Kat McConnell. Current Opinion in Psychology, February 2023.

The Psychology of Hope: A Diagnostic and Prescriptive Account Anthony Scioli. “Historical and Multidisciplinary Perspectives on Hope,” July 2020.

Hope Theory: Rainbows in the Mind C.R. Snyder. Psychological Inquiry, 2002

This article first appeared on The Journalist’s Resource and is republished here under a Creative Commons license.

Don’t Forget…

Did you arrive here from our newsletter? Don’t forget to return to the email to continue learning!

Recommended

Learn to Age Gracefully

Join the 98k+ American women taking control of their health & aging with our 100% free (and fun!) daily emails:

-

The Health Fix – by Dr. Ayan Panja

10almonds is reader-supported. We may, at no cost to you, receive a portion of sales if you purchase a product through a link in this article.

The book is divided into three main sections:

- The foundations

- The aspirations

- The fixes

The foundations are an overview of the things you’re going to need to know, about biology, behaviors, and being human.

The aspirations are research-generated common hopes, desires, dreams and goals of patients who have come to Dr. Panja for help.

The fixes are exactly what you’d hope them to be. They’re strategies, tools, hacks, tips, tricks, to get you from where you are now to where you want to be, health-wise.

The book is well-structured, with deep-dives, summaries, and practical advice of how to make sure everything you’re doing works together as part of the big picture that you’re building for your health.

All in all, a fantastic catch-all book, whatever your health goals.

Share This Post

-

Meningitis Outbreak

10almonds is reader-supported. We may, at no cost to you, receive a portion of sales if you purchase a product through a link in this article.

Don’t Let Your Guard Down

In the US, meningitis is currently enjoying a 10-year high, with its highest levels of infection since 2014.

This is a big deal, given the 10–15% fatality rate of meningitis, even with appropriate medical treatment.

But of course, not everyone gets appropriate medical treatment, especially because symptoms can become life-threatening in a matter of hours.

Most recent stats gave an 18% fatality rate for the cases with known outcomes in the last year:

CDC Emergency | Increase in Invasive Serogroup Y Meningococcal Disease in the United States

The quick facts:

❝Meningococcal disease most often presents as meningitis, with symptoms that may include fever, headache, stiff neck, nausea, vomiting, photophobia, or altered mental status.

[It can also present] as meningococcal bloodstream infection, with symptoms that may include fever and chills, fatigue, vomiting, cold hands and feet, severe aches and pains, rapid breathing, diarrhea, or, in later stages, a dark purple rash.

While initial symptoms of meningococcal disease can at first be non-specific, they worsen rapidly, and the disease can become life-threatening within hours. Immediate antibiotic treatment for meningococcal disease is critical.

Survivors may experience long-term effects such as deafness or amputations of the extremities.❞

~ Ibid.

The good news (but still don’t let your guard down)

Meningococcal bacteria are, happily, not spread as easily as cold and flu viruses.

The greatest risks come from:

- Close and enduring proximity (e.g. living together)

- Oral, or close-to-oral, contact (e.g. kissing, or coughing nearby)

Read more:

CDC | Meningococcal Disease: Causes & How It Spreads

Is there a vaccine?

There is, but it’s usually only offered to those most at risk, which is usually:

- Children

- Immunocompromised people, especially if HIV+

- People taking certain medications (e.g. Solaris or Ultomiris)

Read more:

CDC | Meningococcal Vaccine Recommendations

Will taking immune-boosting supplements help?

Honestly, probably not, but they won’t harm either. The most important thing is: don’t rely on them—too many people pop a vitamin C supplement and then assume they are immune to everything, and it doesn’t work like that.

On a tangential note, for more general immune health, you might also want to check out:

Beyond Supplements: The Real Immune-Boosters!

The short version:

If you or someone you know experiences the above-mentioned symptoms, even if it does not seem too bad, get thee/them to a doctor, and quickly, because the (very short) clock may be ticking already.

Better safe than sorry.

Share This Post

-

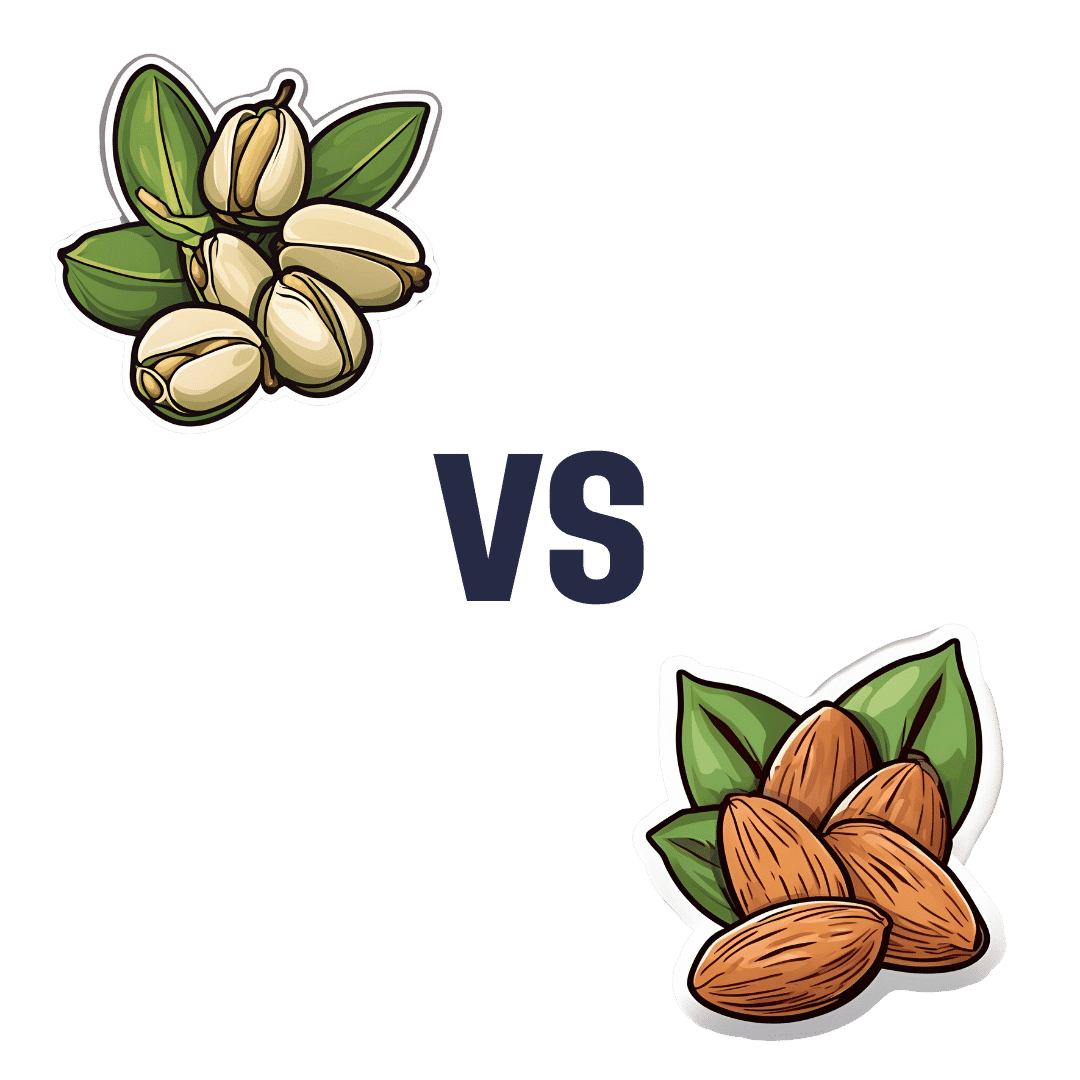

Pistachios vs Almonds – Which is Healthier?

10almonds is reader-supported. We may, at no cost to you, receive a portion of sales if you purchase a product through a link in this article.

Our Verdict

When comparing pistachios to almonds, we picked the almonds.

Why?

It was very close! And those who’ve been following our “This or That” comparisons might be aware that pistachios and almonds have both been winning their respective comparisons with other nuts so far, so today we put them head-to-head.

In terms of macros, almonds have a little more protein and a little more fiber—as well as slightly more fat, though the fats are healthy. Pistachios, meanwhile, are higher in carbs. A moderate win for almonds on the macro front.

When it comes to vitamins, pistachios have more of vitamins A, B1, and B6, while almonds have more of vitamins B2, B3, and E. We could claim a slight victory for pistachios, based on the larger margins, or else a slight victory for almonds, based on vitamin E being a more common nutritional deficiency than vitamin A, and therefore the more useful vitamin to have more of. We’re going to call this category a tie.

In the category of minerals, almonds lead with more calcium, magnesium, manganese, and zinc, while pistachios boast more copper, potassium, and selenium, though the margins are more modest for pistachios. A moderate win for almonds on minerals, therefore.

Adding up the sections gives a win for almonds, but of course, do enjoy both, because both are excellent in their own right.

Want to learn more?

You might like to read:

- Why You Should Diversify Your Nuts!

- Pistachios vs Walnuts – Which is Healthier?

- Almonds vs Cashews – Which is Healthier?

Take care!

Share This Post

Related Posts

-

Infections Here, Infections There…

10almonds is reader-supported. We may, at no cost to you, receive a portion of sales if you purchase a product through a link in this article.

This week in health news, let’s take a look at infections outside and in, and how to walk away from it all (in a good way):

The bird that flu away

This one cannot be described as good news. Basically, bird flu is now already epidemic amongst cows in the US, with 845 herds (not 845 cows; 845 herds) testing positive across 16 states. The US Department of Agriculture earlier this month announced a federal order to test milk nationwide. Researchers welcomed the news, but said it should have happened months ago—before the virus was so entrenched. It currently has a fatality rate of 2–5% in cows; we don’t have enough data to reasonably talk about its fatality rate in humans—yet.

❝It’s disheartening to see so many of the same failures that emerged during the COVID-19 crisis re-emerge❞

~ Tom Bollyky, director of the Global Health Program at the Council on Foreign Relations

Read in full: How America lost control of the bird flu, setting the stage for another pandemic

Related: Cows’ Milk, Bird Flu, & You

Alzheimer’s from the gut upwards

Alzheimer’s is generally thought of as being a purely brain thing, but there’s a link between a [specific] chronic gut infection, and the development of Alzheimer’s disease. This infection is called human cytomegalovirus, or HCMV for short, and usually we’ve all been exposed to it by young adulthood. However, for some people, it lingers in an active state in the gut, wherefrom it may travel to the brain via the vagus nerve “gut-brain highway”. And once there, well, you can guess the rest:

Read in full: The surprising role of gut infection in Alzheimer’s disease

Related: How To Reduce Your Alzheimer’s Risk

Walking back to happiness

Analyzing data from 96,138 adults around the world, showed that more steps meant less depression for participants.

You may be thinking “well yes, depressed people walk less”, but more specifically, increases in activity showed increases in anti-depressive benefits, with even small incremental increases showing correspondingly incremental benefits. Specifically, each additional 1,000 steps per day corresponded to a 9% reduction in depression:

Read in full: Higher daily step counts associated with fewer depressive symptoms

Related: Walking… Better.

Take care!

Don’t Forget…

Did you arrive here from our newsletter? Don’t forget to return to the email to continue learning!

Learn to Age Gracefully

Join the 98k+ American women taking control of their health & aging with our 100% free (and fun!) daily emails:

-

The Lost Art of Silence – by Sarah Anderson

10almonds is reader-supported. We may, at no cost to you, receive a portion of sales if you purchase a product through a link in this article.

From “A Room Of One’s Own” to “Silent Mondays”, from spiritual retreats to noise-cancelling headphones, this book covers the many benefits of silence—and a couple of downsides too.

In an age where most things are available at the touch of a button, a little peaceful solitude can come at quite a premium, but what it offers can effect all manner of physical changes, from reduced stress responses to increased neurogenesis (growing new brain cells).

The tone throughout is a combination of personal and pop-science, and it’s very motivating to find a little more space-between-the-things in life.

The book is best enjoyed in a quiet room.

Bottom line: if you get the feeling sometimes that you could rest and recover fully and properly if you could just find the downtime, this book will help you find exactly that.

Click here to check out the Lost Art of Silence, and find peace and strength in it!

Don’t Forget…

Did you arrive here from our newsletter? Don’t forget to return to the email to continue learning!

Learn to Age Gracefully

Join the 98k+ American women taking control of their health & aging with our 100% free (and fun!) daily emails:

-

Osteoporosis & Exercises: Which To Do (And Which To Avoid)

10almonds is reader-supported. We may, at no cost to you, receive a portion of sales if you purchase a product through a link in this article.

It’s Q&A Day at 10almonds!

Have a question or a request? You can always hit “reply” to any of our emails, or use the feedback widget at the bottom!

In cases where we’ve already covered something, we might link to what we wrote before, but will always be happy to revisit any of our topics again in the future too—there’s always more to say!

As ever: if the question/request can be answered briefly, we’ll do it here in our Q&A Thursday edition. If not, we’ll make a main feature of it shortly afterwards!

So, no question/request too big or small

❝Any idea about the latest research on the most effective exercises for osteoporosis?❞

While there isn’t much new of late in this regard, there is plenty of research!

First, what you might want to avoid:

- Sit-ups, and other exercises with a lot of repeated spinal flexion

- Running, and other high-impact exercises

- Skiing, horse-riding, and other activities with a high risk of falling

- Golf and tennis (both disproportionately likely to result in injuries to wrists, elbows, and knees)

Next, what you might want to bear in mind:

While in principle resistance training is good for building strong bones, good form becomes all the more important if you have osteoporosis, so consider working with a trainer if you’re not 100% certain you know what you’re doing:

Some of the best exercises for osteoporosis are isometric exercises:

5 Isometric Exercises for Osteoporosis (with textual explanations and illustrative GIFs)

You might also like this bone-strengthening exercise routine from corrective exercise specialist Kendra Fitzgerald:

Enjoy!

Don’t Forget…

Did you arrive here from our newsletter? Don’t forget to return to the email to continue learning!

Learn to Age Gracefully

Join the 98k+ American women taking control of their health & aging with our 100% free (and fun!) daily emails: