Cauliflower vs Carrot – Which is Healthier?

10almonds is reader-supported. We may, at no cost to you, receive a portion of sales if you purchase a product through a link in this article.

Our Verdict

When comparing cauliflower to carrot, we picked the cauliflower.

Why?

In terms of macros, cauliflower has nearly 2x the protein while carrot has nearly 2x the carbs and slightly more fiber; we’re calling it a tie in this category.

When it comes to vitamins, cauliflower has more of vitamins B2, B5, B6, B9, C, K, and choline, while carrot has more of vitamins A, B1, B3, and E. Thus, a 7:4 win for cauliflower here.

In the category of minerals, cauliflower has more iron, magnesium, manganese, phosphorus, selenium, and zinc, while carrot has more calcium, copper, and potassium. So, a 6:3 win for cauliflower here.

In short, for overall nutritional density, adding up the sections makes for a clear win for cauliflower, but of course, enjoy either or (preferably) both; diversity is good!

Want to learn more?

You might like to read:

What’s Your Plant Diversity Score?

Take care!

Don’t Forget…

Did you arrive here from our newsletter? Don’t forget to return to the email to continue learning!

Recommended

Learn to Age Gracefully

Join the 98k+ American women taking control of their health & aging with our 100% free (and fun!) daily emails:

-

Resistance Beyond Weights

10almonds is reader-supported. We may, at no cost to you, receive a portion of sales if you purchase a product through a link in this article.

Resistance, Your Way

We’ve talked before about the importance of resistance training:

Resistance Is Useful! (Especially As We Get Older)

And we’ve even talked about how to make resistance training more effective:

(High Intensity Interval Training, but make it High Intensity Resistance Training)

Which resistance training exercises are best?

There are two reasonable correct answers here:

- The resistance training exercises that you will actually do (because it’s no good knowing the best exercise ever if you’re not going to do it because it is in some way offputting to you)

- The resistance training exercises that will prevent you from getting a broken bone in the event of some accident or incident

This latter is interesting, because when people think resistance training, the usually immediate go-to exercises are often things like the bench press, or the chest machine in the gym.

But ask yourself: how often do we hear about some friend or relative who in their old age has broken their humerus?

It can happen, for sure, but it’s not as often as breaking a hip, a tarsal (ankle bones), or a carpal (wrist bones).

So, how can we train to make those bones strong?

Strong bones grow under strong muscles

When archaeologists dig up a skeleton from a thousand years ago, one of the occupations that’s easy to recognize is an archer. Why?

An archer has an unusual frequent exercise: pushing with their left arm while pulling with their right arm. This will strengthen different muscles on each side, and thus, increase bone density in different places on each arm. The left first metacarpal and right first and second metacarpals and phalanges are also a giveaway.

This is because: one cannot grow strong muscles on weak bones (or else the muscles would just break the bones), so training muscles will force the body to strengthen the relevant bones.

So: if you want strong bones, train the muscles attached to those bones

This answers the question of “how am I supposed to exercise my hips” etc.

Weights, bodyweight, resistance bands

If you go to the gym, there’s a machine for everything, and a member of gym staff will be able to advise which of their machines will strengthen which muscles.

If you train with free weights at home:

- Wrist curls (forearm supported and stationary, lifting a dumbbell in your hand, palm-upwards) will strengthen the wrist

- The farmer’s walk (carrying a heavy weight in each hand) will also strengthen your wrist

- A modified version of this involves holding the weight with just your fingertips, and then raising and lowering it by curling and uncurling your fingers)

- Lateral leg raises (you will need ankle-weights for this) will strengthen your ankles and your hips, as will hip abductions (as in today’s featured video), especially with a weight attached.

- Ankle raises (going up on your tip-toes and down again, repeat) while holding weights in your hands will strengthen your ankles

If you don’t like weights:

- Press-ups will strengthen your wrists

- Fingertip press-ups are even better: to do these, do your press-ups as normal, except that the only parts of your hands in contact with the ground are your fingertips

- This same exercise can be done the other way around, by doing pull-ups

- And that same “even better” works by doing pull-ups, but holding the bar only with one’s fingertips, and curling one’s fingers to raise oneself up

- Lateral leg raises and hip abductions can be done with a resistance band instead of with weights. The great thing about these is that whereas weights are a fixed weight, resistance bands will always provide the right amount of resistance (because if it’s too easy, you just raise your leg further until it becomes difficult again, since the resistance offered is proportional to how much tension the band is under).

Remember, resistance training is still resistance training even if “all” you’re resisting is gravity!

If it fells like work, then it’s working

As for the rest of preparing to get older?

Check out:

Training Mobility Ready For Later Life

Take care!

Share This Post

-

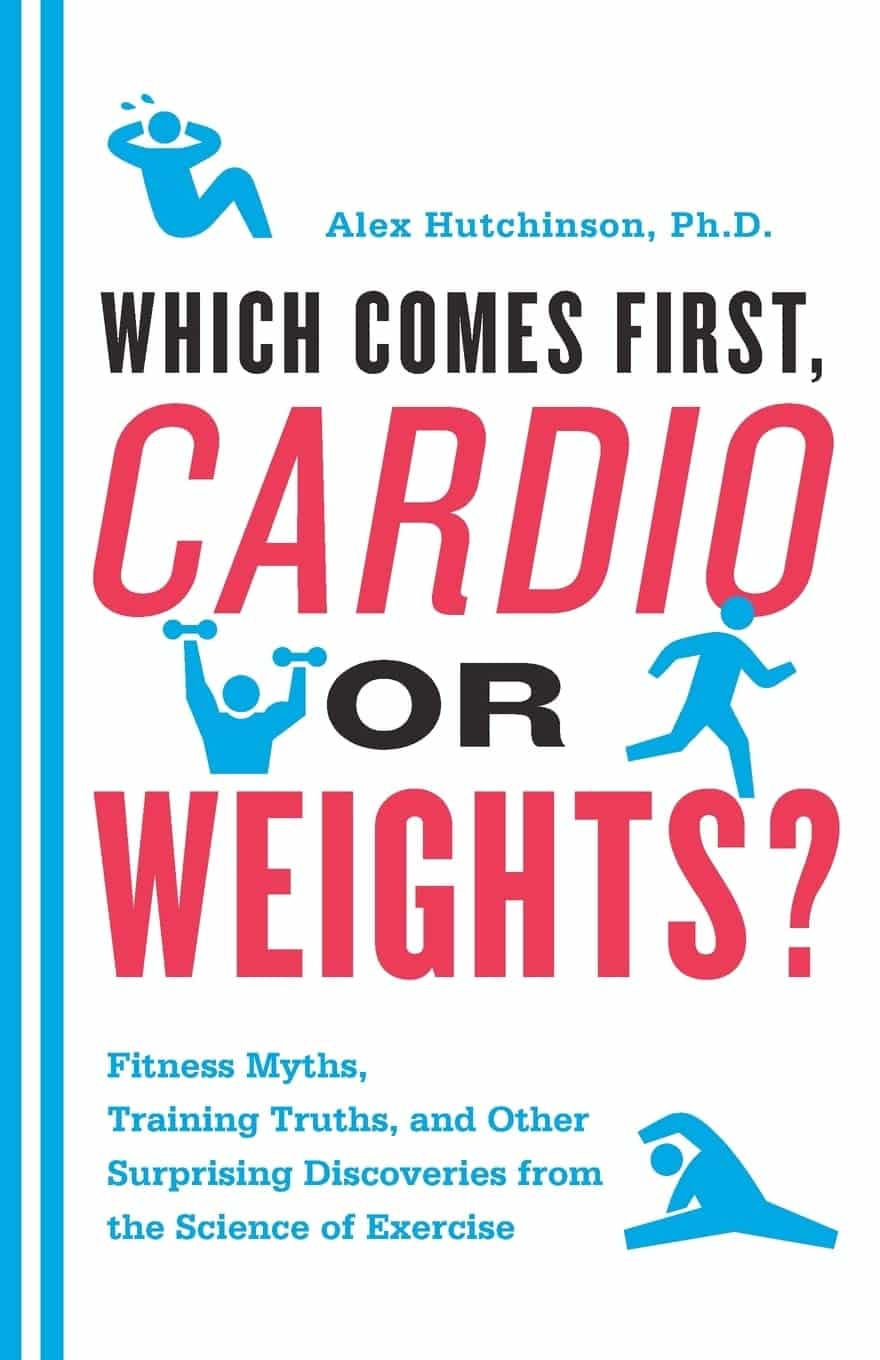

Which Comes First, Cardio or Weights? – by Alex Hutchinson

10almonds is reader-supported. We may, at no cost to you, receive a portion of sales if you purchase a product through a link in this article.

This is a book of questions and answers, myths and busts, and in short, all things exercise.

It’s laid out as many micro-chapters with questions as headers. The explanations are clear and easy to understand, with several citations (of studies and other academic papers) per question.

While it’s quite comprehensive (weighing in at a hefty 300+ pages), it’s not the kind of book where one could just look up any given piece of information that one wants.

Its strength, rather, lies in pre-emptively arming the reader with knowledge, and correcting many commonly-believed myths. It can be read cover-to-cover, or just dipped into per what interests you (the table of contents lists all questions, so it’s easy to flip through).

Bottom line: if you’ve found the world of exercise a little confusing and would like it demystifying, this book will result in a lot of “Oooooh” moments.

Click here to check out Which Comes First, Cardio or Weights?, and know your stuff!

PS: the short answer to the titular question is “mix it up and keep it varied”

Share This Post

-

5 Stretches To Relieve The Pain From Sitting & Poor Posture

10almonds is reader-supported. We may, at no cost to you, receive a portion of sales if you purchase a product through a link in this article.

Sitting is not good for the health, yes often it’s a necessity of modern life, especially if driving. To make things worse, it can often be difficult to remember to maintain good posture the rest of the time, if it’s not a habit. So, while reducing sitting and improving posture are both very good things to do, here are 5 stretches to mitigate the damage meanwhile:

Daily doses:

These are best done at a rate of 2–3 sets daily:

Cat-Cow Stretch:

- Benefits: eases spinal tension, boosts flexibility, improves posture.

- How to: start on all fours, alternate between arching and rounding your back while syncing with your breath (10-15 times).

Butterfly Stretch:

- Benefits: loosens tight hips, improves lower back flexibility, and enhances mobility for activities like squats.

- How to: sit with soles of feet together, let knees fall toward the floor, lean forward slightly, and hold for 30 seconds to 1 minute.

Supine Twist:

- Benefits: unlocks the spine, relieves post-workout tension, and relaxes the shoulders and hips.

- How to: lie on your back, bend knees, twist to one side while keeping shoulders grounded, and hold for 30 seconds to 1 minute per side.

Calf Stretch:

- Benefits: improves ankle mobility, loosens tight calves, and prevents injuries like Achilles tendinitis.

- How to: stand facing a wall, extend one leg back with the heel on the ground, lean into the stretch, or use a step for deeper stretches. Hold for 30 seconds to 1 minute per leg.

Child’s Pose:

- Benefits: decompresses the spine, relaxes hips, and relieves tension in back and thighs.

- How to: start on hands and knees, sit back onto your heels, stretch arms forward, and rest forehead on the mat. Hold for 30 seconds to 1 minute.

For more on each of these, plus visual demonstrations, enjoy:

Click Here If The Embedded Video Doesn’t Load Automatically!

Want to learn more?

You might also like:

10 Tips To Reduce Morning Pain & Stiffness With Arthritis

Take care!

Share This Post

Related Posts

-

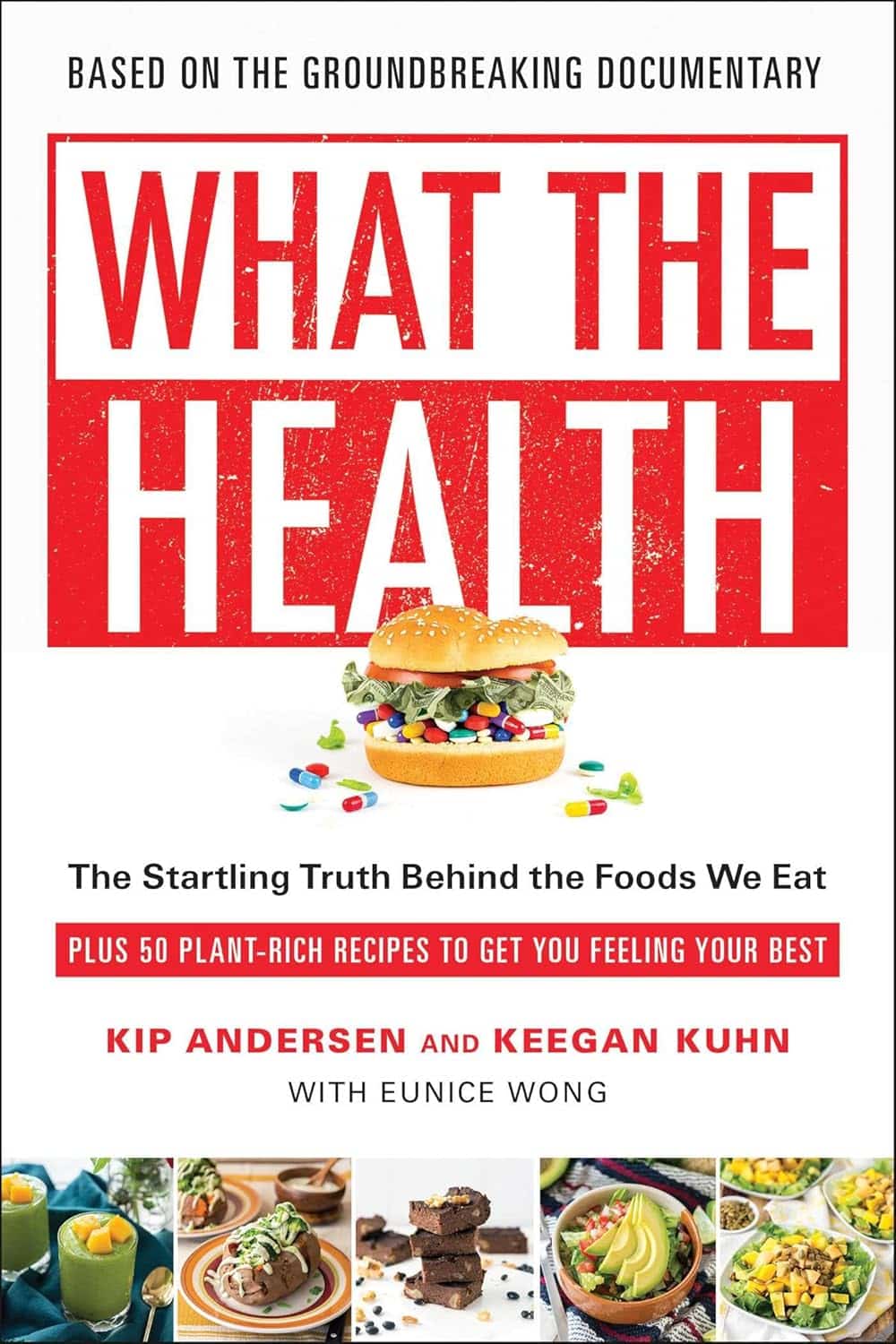

What the Health – by Kip Andersen, Keegan Kuhn, & Eunice Wong

10almonds is reader-supported. We may, at no cost to you, receive a portion of sales if you purchase a product through a link in this article.

This is a book from the makers of the famous documentary of the same name. Which means that yes, they are journalists not scientists, but they got input from very many scientists, doctors, nutritionists, and so forth, for a very reliable result.

It’s worth noting however that while a lot of the book is about the health hazards of a lot of the “Standard American Diet”, or “SAD” as it is appropriately abbreviated, a lot is also about how various industries

bribelobby the government to either push, or give them leeway to push, their products over healthier ones. So, there’s a lot about what would amount to corruption if it weren’t tied up in legalese that makes it just “lobbying” rather than bribery.The style is mostly narrative, albeit with very many citations adding up to 50 pages of references. There’s also a recipe section, which is… fairly basic, and despite getting a shoutout in the subtitle, the recipes are certainly not the real meat of the book.

The recipes themselves are entirely plant-based, and de facto vegan.

Bottom line: this one’s more of a polemic against industry malfeasance than it is a textbook of nutrition science, but there is enough information in here that it could have been the textbook if it wanted to, changing only the style and not the content.

Click here to check out What The Health, and make informed choices about yours!

Don’t Forget…

Did you arrive here from our newsletter? Don’t forget to return to the email to continue learning!

Learn to Age Gracefully

Join the 98k+ American women taking control of their health & aging with our 100% free (and fun!) daily emails:

-

What Most People Don’t Know About HIV

10almonds is reader-supported. We may, at no cost to you, receive a portion of sales if you purchase a product through a link in this article.

What To Know About HIV This World AIDS Day

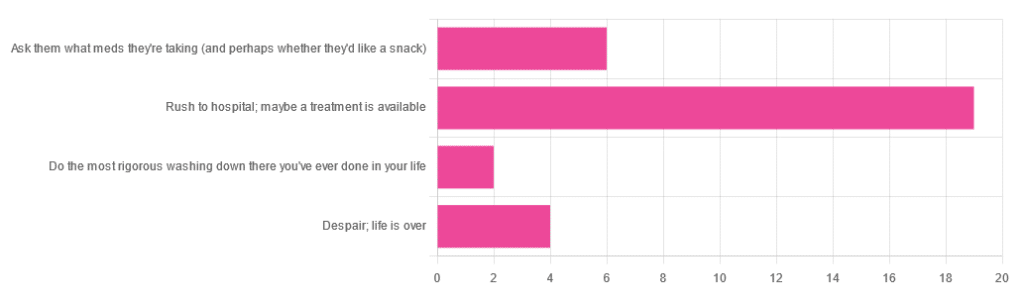

Yesterday, we asked 10almonds readers to engage in a hypothetical thought experiment with us, and putting aside for a moment any reason you might feel the scenario wouldn’t apply for you, asked:

❝You have unprotected sex with someone who, afterwards, conversationally mentions their HIV+ status. Do you…❞

…and got the above-depicted, below-described, set of responses. Of those who responded…

- Just over 60% said “rush to hospital; maybe a treatment is available”

- Just under 20% said “ask them what meds they’re taking (and perhaps whether they’d like a snack)”

- Just over 10% said “despair; life is over”

- Two people said “do the most rigorous washing down there you’ve ever done in your life”

So, what does science say about it?

First, a quick note on terms

- HIV is the Human Immunodeficiency Virus. It does what it says on the tin; it gives humans immunodeficiency. Like many viruses that have become epidemic in humans, it started off in animals (called SIV, because there was no “H” involved yet), which were then eaten by humans, passing the virus to us when it one day mutated to allow that.

- It’s technically two viruses, but that’s beyond the scope of today’s article; for our purposes they are the same. HIV-1 is more virulent and infectious than HIV-2, and is the kind more commonly found in most of the world.

- AIDS is Acquired Immunodeficiency Syndrome, and again, is what it sounds like. When a person is infected with HIV, then without treatment, they will often develop AIDS.

- Technically AIDS itself doesn’t kill people; it just renders people near-defenseless to opportunistic infections (and immune-related diseases such as cancer), since one no longer has a properly working immune system. Common causes of death in AIDS patients include cancer, influenza, pneumonia, and tuberculosis.

People who contract HIV will usually develop AIDS if untreated. Untreated life expectancy is about 11 years.

HIV/AIDS are only a problem for gay people: True or False?

False, unequivocally. Anyone can get HIV and develop AIDS.

The reason it’s more associated with gay men, aside from homophobia, is that since penetrative sex is more likely to pass it on, then if we go with the statistically most likely arrangements here:

- If a man penetrates a woman and passes on HIV, that woman will probably not go on to penetrate someone else

- If a man penetrates a man and passes on HIV, that man could go on to penetrate someone else—and so on

- This means that without any difference in safety practices or promiscuity, it’s going to spread more between men on average, by simple mathematics.

- This is why “men who have sex with men” is the generally-designated higher-risk category.

There is medication to cure HIV/AIDS: True or False?

False so far (though there have been individual case studies of gene treatments that may have cured people—time will tell).

But! There are medications that can prevent HIV from being a life-threatening problem:

- PrEP (Pre-Exposure Prophylaxis) is a medication that one can take in advance of potential exposure to HIV, to guard against it.

- This is a common choice for people aren’t sure about their partners’ statuses, or people working in risky environments.

- PEP (Post-Exposure Prophylaxis) is a medication that one can take after potential exposure to HIV, to “nip it in the bud”.

- Those of you who were rushing to hospital in our poll, this is what you’re rushing there for.

- ARVs (Anti-RetroVirals) are a class of medications (there are different options; we don’t have room to distinguish them) that reduce an HIV+ person’s viral load to undetectable levels.

- Those of you who were asking what meds your partner was taking, these will be those meds. Also, most of them are to be taken in the morning with food, so that’s what the snack was for.

If someone is HIV+, the risk of transmission in unprotected sex is high: True or False?

True or False, with false being the far more likely. It depends on their medications, and this is why you were asking. If someone is on ARVs and their viral load is undetectable (as is usual once someone has been on ARVs for 6 months), they cannot transmit HIV to you.

U=U is not a fancy new emoticon, it means “undetectable = untransmittable”, which is a mathematically true statement in the case of HIV viral loads.

See: NIH | HIV Undetectable=Untransmittable (U=U)

If you’re thinking “still sounds risky to me”, then consider this:

You are safer having unprotected sex with someone who is HIV+ and on ARVs with an undetectable viral load, than you are with someone you are merely assuming is HIV- (perhaps you assume it because “surely this polite blushing young virgin of a straight man won’t give me cooties” etc)

Note that even your monogamous partner of many decades could accidentally contract HIV due to blood contamination in a hospital or an accident at work etc, so it’s good practice to also get tested after things that involve getting stabbed with needles, cut in a risky environment, etc.

If you’re concerned about potential stigma associated with HIV testing, you can get kits online:

CDC | How do I find an HIV self-test?

(these are usually fingerprick blood tests, and you can either see the results yourself at home immediately, or send it in for analysis, depending on the kit)

If I get HIV, I will get AIDS and die: True or False?

False, assuming you get treatment promptly and keep taking it. So those of you who were at “despair; life is over” can breathe a sigh of relief now.

However, if you get HIV, it does currently mean you will have to take those meds every day for the rest of your (no reason it shouldn’t be long and happy) life.

So, HIV is definitely still something to avoid, because it’s not great to have to take a life-saving medication every day. For a little insight as to what that might be like:

HIV.gov | Taking HIV Medication Every Day: Tips & Challenges

(as you’ll see there, there are also longer-lasting injections available instead of daily pulls, but those are much less widely available)

Summary

Some quick take-away notes-in-a-nutshell:

- Getting HIV may have been a death sentence in the 1980s, but nowadays it’s been relegated to the level of “serious inconvenience”.

- Happily, it is very preventable, with PrEP, PEP, and viral loads so low that they can’t transmit HIV, thanks to ARVs.

- Washing will not help, by the way. Safe sex will, though!

- As will celibacy and/or sexual exclusivity in seroconcordant relationships, e.g. you have the same (known! That means actually tested recently! Not just assumed!) HIV status as each other.

- If you do get it, it is very manageable with ARVs, but prevention is better than treatment

- There is no certain cure—yet. Some people (small number of case studies) may have been cured already with gene therapy, but we can’t know for sure yet.

Want to know more? Check out:

Take care!

Don’t Forget…

Did you arrive here from our newsletter? Don’t forget to return to the email to continue learning!

Learn to Age Gracefully

Join the 98k+ American women taking control of their health & aging with our 100% free (and fun!) daily emails:

-

Avoiding Anemia (More Than Just “Get More Iron”)

10almonds is reader-supported. We may, at no cost to you, receive a portion of sales if you purchase a product through a link in this article.

The Iron Dilemma: Factors To Consider

Anemia affects around 10% of American seniors, and that number jumps to 34–39% if there’s a comorbidity such as diabetes, hypertension, or hypercholesterolemia, which in turn climbs with increasing age or with other chronic conditions:

So, what can we do about it?

Get iron yes, but how?

We’d be remiss not to say: yes, do of course make sure you get plenty of iron.

Most people know that red meats, which are terrible for the heart and for cancer risk, are good sources of iron.

Well, good insofar as they provide plenty of it! They’re bad for other reasons.

❝Studies consistently show that consumption of red meat has been contributory to a multitude of chronic conditions such as diabetes, CVD, and malignancies.

There are various emerging reasons that strengthen this link-from the basic constituents of red meat like the heme iron component, the metabolic reactions that take place after consumption, and finally to the methods used to cook it.

The causative links show that even occasional use raises the risk of T2DM.❞

Source: Red Meat Consumption (Heme Iron Intake) and Risk for Diabetes and Comorbidities?

To heme or not to heme

Did you catch that in the middle there, about the heme iron component?

Dietary iron is broadly divided into two kinds: heme, and non-heme.

- Heme iron comes from animals

- Non-heme iron comes from plants

Bad news for vegans: non-heme iron is not so easily absorbed as heme iron.

This means that if you’re just eating plants, the RDA may be significantly lowballing the amount actually required. As a rule, about 1.8x more iron may be needed for vegans, to compensate for it being less easily absorbed.

Why this happens: it’s because of the phytic acid / phytate in the plants that contain the iron, blocking its absorption.

Good news for vegans: however, taking iron with vitamin C increases its absorption rate by about 5x better absorption, and several other side-along nutrients do similarly, including allium (from garlic), carotenoids (from many colorful plants), and fermented foods.

Why this happens: it’s because they bind with similar sites as phytic acid, without causing the same effect. To make a metaphor: these foods steal phytic acid’s parking space, so phytic acid can’t do its iron-blocking thing.

By happy coincidence, today’s featured recipe has all of these things in, by the way (vitamin C, allium, carotenoids, and fermented foods), and the star ingredient (fava beans) is a rich source of iron.

What are good sources of iron, then?

In the category of plants:

- Beans (pick your favorites / eat a variety)

- Lentils (pick your favorites / eat a variety)

- Greens (especially dark leafy greens)

- Apricots (you can get these dried, for convenience!)

- Dark chocolate (5mg per 1oz square!)*

*Ok, technically dark chocolate is not a plant; cacao is a plant; dark chocolate is usually plant-based, though, as there is no reason to add milk.

In the category of dairy products:

That’s not a publication error; dairy products are just not great for iron. Cheeses are more nutrient-dense than milk, and have less than 0.5mg per oz, in other words, the top dairy product has around 10x less iron than dark chocolate, which came in 5th place and let’s face it, we were doing broad categories there. If we listed all the beans, lentils, greens, etc it’d be a much longer list.

Eggs, which are sometimes considered under the category of dairy by virtue of not being an animal (yet!) but an animal product, have around 1mg per egg, by the way, so considering eggs are nearer 2oz, that’s not much better than the cheese.

“But what about if…”

The above is good science and general good advice for most people. That said, some people may have conditions that preclude the foods we recommended, or have other considerations, and so things may be different. Anemia can sometimes be caused by things that can’t be fixed by diet (beyond the scope of today’s article; another time, perhaps), but for example, if you have leukemia then definitely discuss things with your doctors first. Other illnesses, and some medications, can also have troublesome effects that can contribute to anemia. Again, we can offer very good general information here, but we don’t know your medical history, and our standard legal/medical disclaimer applies as always.

See also: Do We Need Animal Products To Be Healthy?

Take care!

Don’t Forget…

Did you arrive here from our newsletter? Don’t forget to return to the email to continue learning!

Learn to Age Gracefully

Join the 98k+ American women taking control of their health & aging with our 100% free (and fun!) daily emails: