What’s the difference between wholemeal and wholegrain bread? Not a whole lot

10almonds is reader-supported. We may, at no cost to you, receive a portion of sales if you purchase a product through a link in this article.

If you head to the shops to buy bread, you’ll face a variety of different options.

But it can be hard to work out the difference between all the types on sale.

For instance, you might have a vague idea that wholemeal or wholegrain bread is healthy. But what’s the difference?

Here’s what we know and what this means for shoppers in Australia and New Zealand.

Let’s start with wholemeal bread

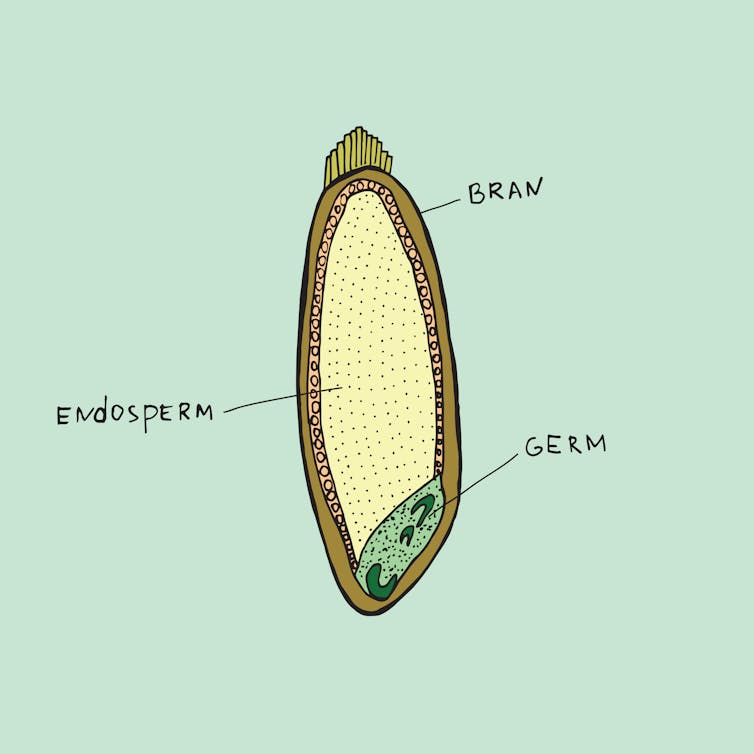

According to Australian and New Zealand food standards, wholemeal bread is made from flour containing all parts of the original grain (endosperm, germ and bran) in their original proportions.

Because it contains all parts of the grain, wholemeal bread is typically darker in colour and slightly more brown than white bread, which is made using only the endosperm.

How about wholegrain bread?

Australian and New Zealand food standards define wholegrain bread as something that contains either the intact grain (for instance, visible grains) or is made from processed grains (flour) where all the parts of the grain are present in their original proportions.

That last part may sound familiar. That’s because wholegrain is an umbrella term that encompasses both bread made with intact grains and bread made with wholemeal flour. In other words, wholemeal bread is a type of wholegrain bread, just like an apple is a type of fruit.

Don’t be confused by labels such as “with added grains”, “grainy” or “multigrain”. Australian and New Zealand food standards don’t define these so manufacturers can legally add a small amount of intact grains to white bread to make the product appear healthier. This doesn’t necessarily make these products wholegrain breads.

So unless a product is specifically called wholegrain bread, wholemeal bread or indicates it “contains whole grain”, it is likely to be made from more refined ingredients.

Which one’s healthier?

So when thinking about which bread to choose, both wholemeal and wholegrain breads are rich in beneficial compounds including nutrients and fibre, more so than breads made from further-refined flour, such as white bread.

The presence of these compounds is what makes eating wholegrains (including wholemeal bread) beneficial for our overall health. Research has also shown eating wholegrains helps reduce the risk of common chronic diseases, such as heart disease.

The table below gives us a closer look at the nutritional composition of these breads, and shows some slight differences.

Wholegrain bread is slightly higher in fibre, protein, niacin (vitamin B3), iron, zinc, phosphorus and magnesium than wholemeal bread. But wholegrain bread is lower in carbohydrates, thiamin (vitamin B1) and folate (vitamin B9).

However the differences are relatively small when considering how these contribute to your overall dietary intake.

Which one should I buy?

Next time you’re shopping, look for a wholegrain bread (one made from wholemeal flour that has intact grains and seeds throughout) as your number one choice for fibre and protein, and to support overall health.

If you can’t find wholegrain bread, wholemeal bread comes in a very close second.

Wholegrain and wholemeal bread tend to cost the same, but both tend to be more expensive than white bread.

Margaret Murray, Senior Lecturer, Nutrition, Swinburne University of Technology

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Don’t Forget…

Did you arrive here from our newsletter? Don’t forget to return to the email to continue learning!

Recommended

Learn to Age Gracefully

Join the 98k+ American women taking control of their health & aging with our 100% free (and fun!) daily emails:

-

What is a ‘vaginal birth after caesarean’ or VBAC?

10almonds is reader-supported. We may, at no cost to you, receive a portion of sales if you purchase a product through a link in this article.

A vaginal birth after caesarean (known as a VBAC) is when a woman who has had a caesarean has a vaginal birth down the track.

In Australia, about 12% of women have a vaginal birth for a subsequent baby after a caesarean. A VBAC is much more common in some other countries, including in several Scandinavian ones, where 45-55% of women have one.

So what’s involved? What are the risks? And who’s most likely to give birth vaginally the next time round?

MVelishchuk/Shutterstock What happens? What are the risks?

When a woman chooses a VBAC she is cared for much like she would during a planned vaginal birth.

However, an induction of labour is avoided as much as possible, due to the slightly increased risk of the caesarean scar opening up (known as uterine rupture). This is because the medication used in inductions can stimulate strong contractions that put a greater strain on the scar.

In fact, one of the main reasons women may be recommended to have a repeat caesarean over a vaginal birth is due to an increased chance of her caesarean scar rupturing.

This is when layers of the uterus (womb) separate and an emergency caesarean is needed to deliver the baby and repair the uterus.

Uterine rupture is rare. It occurs in about 0.2-0.7% of women with a history of a previous caesarean. A uterine rupture can also happen without a previous caesarean, but this is even rarer.

However, uterine rupture is a medical emergency. A large European study found 13% of babies died after a uterine rupture and 10% of women needed to have their uterus removed.

The risk of uterine rupture increases if women have what’s known as complicated or classical caesarean scars, and for women who have had more than two previous caesareans.

Most care providers recommend you avoid getting pregnant again for around 12 months after a caesarean, to allow full healing of the scar and to reduce the risk of the scar rupturing.

National guidelines recommend women attempt a VBAC in hospital in case emergency care is needed after uterine rupture.

During a VBAC, recommendations are for closer monitoring of the baby’s heart rate and vigilance for abnormal pain that could indicate a rupture is happening.

If labour is not progressing, a caesarean would then usually be advised.

Giving birth in hospital is recommended for a vaginal birth after a caesarean. christinarosepix/Shutterstock Why avoid multiple caesareans?

There are also risks with repeat caesareans. These include slower recovery, increased risks of the placenta growing abnormally in subsequent pregnancies (placenta accreta), or low in front of the cervix (placenta praevia), and being readmitted to hospital for infection.

Women reported birth trauma and post-traumatic stress more commonly after a caesarean than a vaginal birth, especially if the caesarean was not planned.

Women who had a traumatic caesarean or disrespectful care in their previous birth may choose a VBAC to prevent re-traumatisation and to try to regain control over their birth.

We looked at what happened to women

The most common reason for a caesarean section in Australia is a repeat caesarean. Our new research looked at what this means for VBAC.

We analysed data about 172,000 low-risk women who gave birth for the first time in New South Wales between 2001 and 2016.

We found women who had an initial spontaneous vaginal birth had a 91.3% chance of having subsequent vaginal births. However, if they had a caesarean, their probability of having a VBAC was 4.6% after an elective caesarean and 9% after an emergency one.

We also confirmed what national data and previous studies have shown – there are lower VBAC rates (meaning higher rates of repeat caesareans) in private hospitals compared to public hospitals.

We found the probability of subsequent elective caesarean births was higher in private hospitals (84.9%) compared to public hospitals (76.9%).

Our study did not specifically address why this might be the case. However, we know that in private hospitals women access private obstetric care and experience higher caesarean rates overall.

What increases the chance of success?

When women plan a VBAC there is a 60-80% chance of having a vaginal birth in the next birth.

The success rates are higher for women who are younger, have a lower body mass index, have had a previous vaginal birth, give birth in a home-like environment or with midwife-led care.

For instance, an Australian study found women who accessed continuity of care with a midwife were more likely to have a successful VBAC compared to having no continuity of care and seeing different care providers each time.

An Australian national survey we conducted found having continuity of care with a midwife when planning a VBAC can increase women’s sense of control and confidence, increase their chance to be upright and active in labour and result in a better relationship with their health-care provider.

Seeing the same midwife throughout your maternity care can help. Tyler Olson/Shutterstock Why is this important?

With the rise of caesareans globally, including in Australia, it is more important than ever to value vaginal birth and support women to have a VBAC if this is what they choose.

Our research is also a reminder that how a woman gives birth the first time greatly influences how she gives birth after that. For too many women, this can lead to multiple caesareans, not all of them needed.

Hannah Dahlen, Professor of Midwifery, Associate Dean Research and HDR, Midwifery Discipline Leader, Western Sydney University; Hazel Keedle, Senior Lecturer of Midwifery, Western Sydney University, and Lilian Peters, Adjunct Research Fellow, Western Sydney University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Share This Post

-

Having an x-ray to diagnose knee arthritis might make you more likely to consider potentially unnecessary surgery

10almonds is reader-supported. We may, at no cost to you, receive a portion of sales if you purchase a product through a link in this article.

Osteoarthritis is a leading cause of chronic pain and disability, affecting more than two million Australians.

Routine x-rays aren’t recommended to diagnose the condition. Instead, GPs can make a diagnosis based on symptoms and medical history.

Yet nearly half of new patients with knee osteoarthritis who visit a GP in Australia are referred for imaging. Osteoarthritis imaging costs the health system A$104.7 million each year.

Our new study shows using x-rays to diagnose knee osteoarthritis can affect how a person thinks about their knee pain – and can prompt them to consider potentially unnecessary knee replacement surgery.

pikselstock/Shutterstock What happens when you get osteoarthritis?

Osteoarthritis arises from joint changes and the joint working extra hard to repair itself. It affects the entire joint, including the bones, cartilage, ligaments and muscles.

It is most common in older adults, people with a high body weight and those with a history of knee injury.

Many people with knee osteoarthritis experience persistent pain and have difficulties with everyday activities such as walking and climbing stairs.

How is it treated?

In 2021–22, more than 53,000 Australians had knee replacement surgery for osteoarthritis.

Hospital services for osteoarthritis, primarily driven by joint replacement surgery, cost $3.7 billion in 2020–21.

While joint replacement surgery is often viewed as inevitable for osteoarthritis, it should only be considered for those with severe symptoms who have already tried appropriate non-surgical treatments. Surgery carries the risk of serious adverse events, such as blood clot or infection, and not everyone makes a full recovery.

Most people with knee osteoarthritis can manage it effectively with:

- education and self-management

- exercise and physical activity

- weight management (if necessary)

- medicines for pain relief (such as paracetamol and non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs).

Debunking a common misconception

A common misconception is that osteoarthritis is caused by “wear and tear”.

However, research shows the extent of structural changes seen in a joint on an x-ray does not reflect the level of pain or disability a person experiences, nor does it predict how symptoms will change.

Some people with minimal joint changes have very bad symptoms, while others with more joint changes have only mild symptoms. This is why routine x-rays aren’t recommended for diagnosing knee osteoarthritis or guiding treatment decisions.

Instead, guidelines recommend a “clinical diagnosis” based on a person’s age (being 45 years or over) and symptoms: experiencing joint pain with activity and, in the morning, having no joint-stiffness or stiffness that lasts less than 30 minutes.

Despite this, many health professionals in Australia continue to use x-rays to diagnose knee osteoarthritis. And many people with osteoarthritis still expect or want them.

What did our study investigate?

Our study aimed to find out if using x-rays to diagnose knee osteoarthritis affects a person’s beliefs about osteoarthritis management, compared to a getting a clinical diagnosis without x-rays.

We recruited 617 people from across Australia and randomly assigned them to watch one of three videos. Each video showed a hypothetical consultation with a general practitioner about knee pain.

People with knee osteoarthritis can have difficulties getting down stairs. beeboys/Shutterstock One group received a clinical diagnosis of knee osteoarthritis based on age and symptoms, without being sent for an x-ray.

The other two groups had x-rays to determine their diagnosis (the doctor showed one group their x-ray images and not the other).

After watching their assigned video, participants completed a survey about their beliefs about osteoarthritis management.

What did we find?

People who received an x-ray-based diagnosis and were shown their x-ray images had a 36% higher perceived need for knee replacement surgery than those who received a clinical diagnosis (without x-ray).

They also believed exercise and physical activity could be more harmful to their joint, were more worried about their condition worsening, and were more fearful of movement.

Interestingly, people were slightly more satisfied with an x-ray-based diagnosis than a clinical diagnosis.

This may reflect the common misconception that osteoarthritis is caused by “wear and tear” and an assumption that the “damage” inside the joint needs to be seen to guide treatment.

What does this mean for people with osteoarthritis?

Our findings show why it’s important to avoid unnecessary x-rays when diagnosing knee osteoarthritis.

While changing clinical practice can be challenging, reducing unnecessary x-rays could help ease patient anxiety, prevent unnecessary concern about joint damage, and reduce demand for costly and potentially unnecessary joint replacement surgery.

It could also help reduce exposure to medical radiation and lower health-care costs.

Previous research in osteoarthritis, as well as back and shoulder pain, similarly shows that when health professionals focus on joint “wear and tear” it can make patients more anxious about their condition and concerned about damaging their joints.

If you have knee osteoarthritis, know that routine x-rays aren’t needed for diagnosis or to determine the best treatment for you. Getting an x-ray can make you more concerned and more open to surgery. But there are a range of non-surgical options that could reduce pain, improve mobility and are less invasive.

Belinda Lawford, Senior Research Fellow in Physiotherapy, The University of Melbourne; Kim Bennell, Professor of Physiotherapy, The University of Melbourne; Rana Hinman, Professor in Physiotherapy, The University of Melbourne, and Travis Haber, Postdoctoral Research Fellow in Physiotherapy, The University of Melbourne

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Share This Post

-

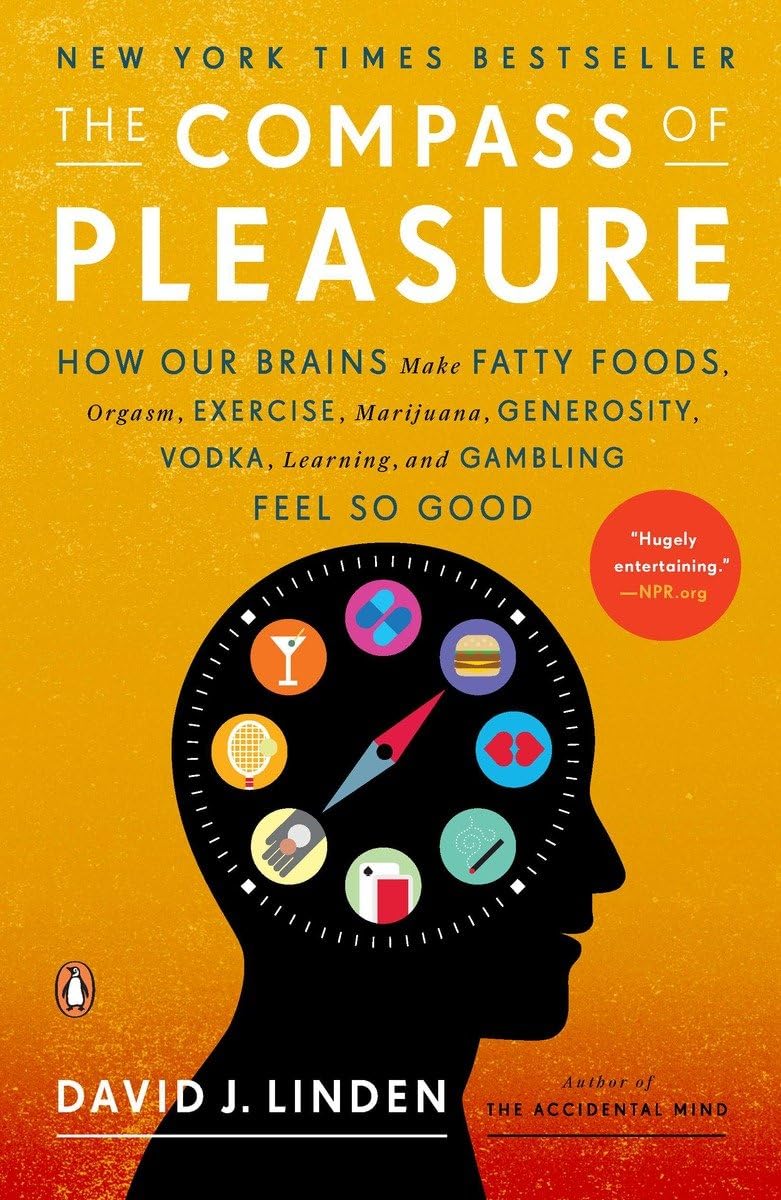

The Compass of Pleasure – by Dr. David Linden

10almonds is reader-supported. We may, at no cost to you, receive a portion of sales if you purchase a product through a link in this article.

There are a lot of books about addiction, so what sets this one apart?

Mostly, it’s that this one maintains that addiction is neither good nor bad per se—just, some behaviors and circumstances are. Behaviors and circumstances caused, directly or indirectly, by addiction.

But, Dr. Linden argues, not every addiction has to be so. Especially behavioral addictions; the rush of dopamine one gets from a good session at the gym or learning a new language, that’s not a bad thing, even if they can fundamentally be addictions too.

Similarly, we wouldn’t be here as a species without some things that rely on some of the same biochemistry as addictions; orgasms and eating food, for example. Yet, those very same urges can also inconvenience us, and in the case of foods and other substances, can harm our health.

In this book, the case is made for shifting our addictive tendencies to healthier addictions, and enough information is given to help us do so.

Bottom line: if you’d like to understand what is going on when you get waylaid by some temptation, and how to be tempted to better things, this book can give the understanding to do just that.

Click here to check out The Compass of Pleasure, and make yours work in your favor!

Share This Post

Related Posts

-

Finding Peace at the End of Life – by Henry Fersko-Weiss

10almonds is reader-supported. We may, at no cost to you, receive a portion of sales if you purchase a product through a link in this article.

This is not the most cheery book we’ve reviewed, but it is an important one. From its first chapter, with “a tale of two deaths”, one that went as well as can be reasonably expected, and the other one not so much, it presents a lot of choices.

The book is not prescriptive in its advice regarding how to deal with these choices, but rather, investigative. It’s thought-provoking, and asks questions—tacitly and overtly.

While the subtitle says “for families and caregivers”, it’s as much worth when it comes to managing one’s own mortality, too, by the way.

As for the scope of the book, it covers everything from terminal diagnosis, through the last part of life, to the death itself, to all that goes on shortly afterwards.

Stylewise, it’s… We’d call it “easy-reading” for style, but obviously the content is very heavy, so you might want to read it a bit at a time anyway, depending on how sensitive to such topics you are.

Bottom line: this book is not exactly a fun read, but it’s a very worthwhile one, and a good way to avoid regrets later.

Don’t Forget…

Did you arrive here from our newsletter? Don’t forget to return to the email to continue learning!

Learn to Age Gracefully

Join the 98k+ American women taking control of their health & aging with our 100% free (and fun!) daily emails:

-

Why Some People Get Sick More (And How To Not Be One Of Them)

10almonds is reader-supported. We may, at no cost to you, receive a portion of sales if you purchase a product through a link in this article.

Some people have never yet had COVID (so far so good, this writer included); others are on their third bout already; others have not been so lucky and are no longer with us to share their stories.

Obviously, even the healthiest and/or most careful person can get sick, and it would be folly to be complacent and think “I’m not a person who gets sick; that happens to other people”.

Nor is COVID the only thing out there to worry about; there’s always the latest outbreak-du-jour of something, and there are always the perennials such as cold and flu—which are also not to be underestimated, because both weaken us to other things, and flu has killed very many, from the 50,000,000+ in the 1918 pandemic, to the 700,000ish that it kills each year nowadays.

And then there are the combination viruses:

Move over, COVID and Flu! We Have “Hybrid Viruses” To Contend With Now

So, why are some people more susceptible?

Firstly, some people are simply immunocompromised. This means for example that:

- perhaps they have an inflammatory/autoimmune disease of some kind (e.g. lupus, rheumatoid arthritis, type 1 diabetes), or…

- perhaps they are taking immunosuppressants for some reason (e.g. because they had an organ transplant), or…

- perhaps they have a primary infection that leaves them vulnerable to secondary infections. Most infections will do this to some degree or another, but some are worse for it than others; untreated HIV is a clear example. The HIV itself may not kill people, but (if untreated) the resultant AIDS will leave a person open to being killed by almost any passing opportunistic pathogen. Pneumonia of various kinds being high on the list, but it could even be something as simple as the common cold, without a working immune system to fight it.

See also: How To Prevent (Or Reduce) Inflammation

And for that matter, since pneumonia is a very common last-nail-in-the-coffin secondary infection (especially: older people going into hospital with one thing, getting a secondary infection and ultimately dying as a result), it’s particularly important to avoid that, so…

See also: Pneumonia: What We Can & Can’t Do About It

Secondly, some people are not immunocompromised per the usual definition of the word, but their immune system is, arguably, compromised.

Cortisol, the stress hormone, is an immunosuppressant. We need cortisol to live, but we only need it in small bursts here and there (such as when we are waking up the morning). When high cortisol levels become chronic, so too does cortisol’s immunosuppressant effect.

Top things that cause elevated cortisol levels include:

- Stress

- Alcohol

- Smoking

Thus, the keys here are to 1) not smoke 2) not drink, ideally, or at least keep consumption low, but honestly even one drink will elevate cortisol levels, so it’s better not to, and 3) manage stress.

See also: Lower Your Cortisol! (Here’s Why & How)

Other modifiable factors

Being aware of infection risk and taking steps to reduce it (e.g. avoiding being with many people in confined indoor places, masking as appropriate, handwashing frequently) is a good preventative strategy, along with of course getting any recommended vaccines as they come available.

What if they fail? How can we boost the immune system?

We talked about not sabotaging the immune system, but what about actively boosting it? The answer is yes, we certainly can (barring serious medical reasons why not), as there are some very important lifestyle factors too:

Beyond Supplements: The Real Immune-Boosters!

One final last-line thing…

Since if we do get an infection, it’s better to know sooner rather than later… A recent study shows that wearable activity trackers can (if we pay attention to the right things) help predict disease, including highlighting COVID status (positive or negative) about as accurately (88% accuracy) as rapid screening tests. Here’s a pop-science article about it:

Wearable activity trackers show promise in detecting early signals of disease

Take care!

Don’t Forget…

Did you arrive here from our newsletter? Don’t forget to return to the email to continue learning!

Learn to Age Gracefully

Join the 98k+ American women taking control of their health & aging with our 100% free (and fun!) daily emails:

-

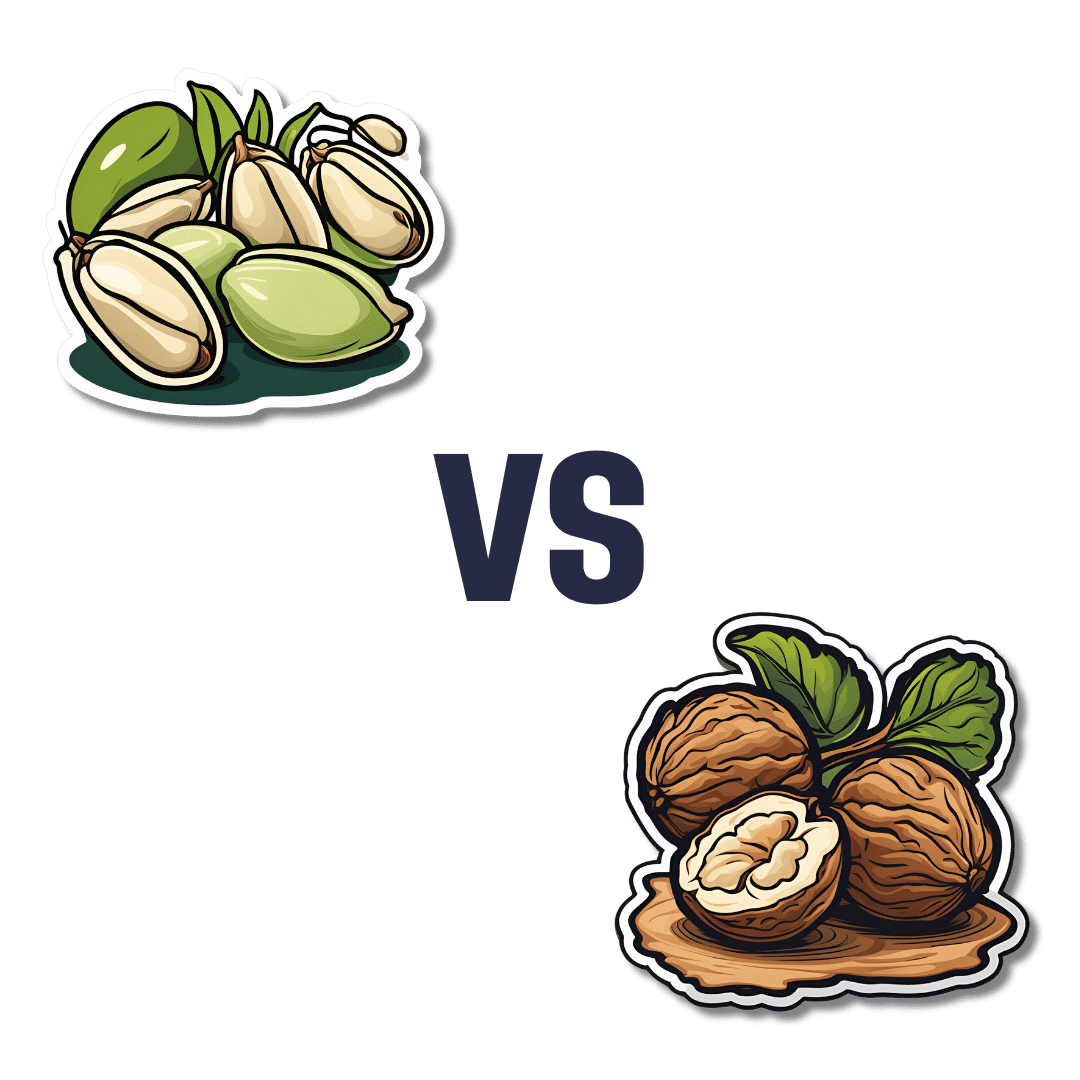

Pistachios vs Walnuts – Which is Healthier?

10almonds is reader-supported. We may, at no cost to you, receive a portion of sales if you purchase a product through a link in this article.

Our Verdict

When comparing pistachios to walnuts, we picked the pistachios.

Why?

Pistachios have more protein and fiber, while walnuts have more fat (though the fats are famously healthy, the same is true of the fats in pistachios).

In the category of vitamins, pistachios have several times more* of vitamins A, B1, B6, C, and E, while walnuts boast only a little more of vitamin B9. They are approximately equal on other vitamins they both contain.

*actually 25x more vitamin A, but the others are 2x, 3x, 4x more.

When it comes to minerals, things are more even; pistachios have more iron, phosphorus, potassium, and selenium, while walnuts have more copper, magnesium, manganese, and zinc. So this category’s a tie.

So given two clear wins for pistachios, and one tie, it’s evident that pistachios win the day.

However! Do enjoy both of these nuts; we often mention that diversity is good in general, and in this case, it’s especially true because of the different mineral profiles, and also because in terms of the healthy fats that they offer, pistachios offer more monounsaturated fats and walnuts offer more polyunsaturated fats; both are healthy, just different.

They’re about equal on saturated fat, in case you were wondering, as it makes up about 6% of the total fats in both cases.

Want to learn more?

You might like to read:

Why You Should Diversify Your Nuts

Take care!

Don’t Forget…

Did you arrive here from our newsletter? Don’t forget to return to the email to continue learning!

Learn to Age Gracefully

Join the 98k+ American women taking control of their health & aging with our 100% free (and fun!) daily emails: