Pumpkin Seeds vs Watermelon Seeds – Which is Healthier?

10almonds is reader-supported. We may, at no cost to you, receive a portion of sales if you purchase a product through a link in this article.

Our Verdict

When comparing pumpkin seeds to watermelon seeds, we picked the watermelon.

Why?

Starting with the macros: pumpkin seeds have a lot more carbs, while watermelon seeds have a lot more protein, despite pumpkin seeds being famous for such. They’re about equal on fiber. In terms of fats, watermelon seeds are higher in fats, and yes, these are healthy fats, mostly polyunsaturated.

When it comes to vitamins, pumpkin seeds are marginally higher in vitamins A and C, while watermelon seeds are a lot higher in vitamins B1, B2, B3, B5, B6, and B9. An easy win for watermelon seeds here.

In the category of minerals, despite being famous for zinc, pumpkin seeds are higher only in potassium, while watermelon seeds are higher in iron, magnesium, manganese, and phosphorus; the two seeds are equal on calcium, copper, and zinc. Another win for watermelon seeds.

In short, enjoy both, but watermelon has more to offer. Of course, if buying just the seeds and not the whole fruit, it’s generally easier to find pumpkin seeds than watermelon seeds, so do bear in mind that pumpkin seeds’ second place isn’t that bad here—it’s just a case of a very nutritious food looking bad by standing next to an even better one.

Want to learn more?

You might like to read:

Seed Saving Secrets – by Alice Mirren

Take care!

Don’t Forget…

Did you arrive here from our newsletter? Don’t forget to return to the email to continue learning!

Recommended

Learn to Age Gracefully

Join the 98k+ American women taking control of their health & aging with our 100% free (and fun!) daily emails:

The Not-So-Sweet Science Of Sugar Addiction

10almonds is reader-supported. We may, at no cost to you, receive a portion of sales if you purchase a product through a link in this article.

One

LumpMechanism Of Addiction Or Two?

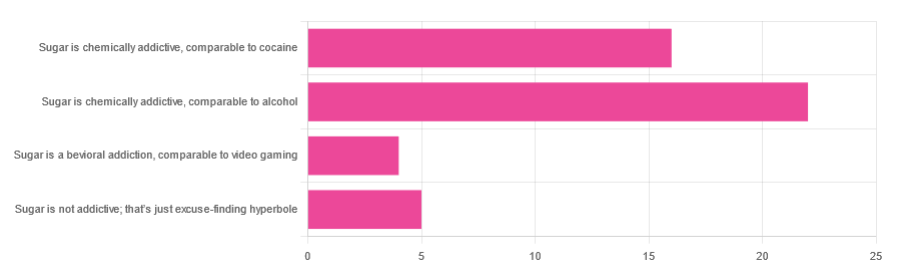

In Tuesday’s newsletter, we asked you to what extent, if any, you believe sugar is addictive; we got the above-depicted, below-described, set of responses:

- About 47% said “Sugar is chemically addictive, comparable to alcohol”

- About 34% said “Sugar is chemically addictive, comparable to cocaine”

- About 11% said “Sugar is not addictive; that’s just excuse-finding hyperbole”

- About 9% said “Sugar is a behavioral addiction, comparable to video gaming”

So what does the science say?

Sugar is not addictive; that’s just excuse-finding hyperbole: True or False?

False, by broad scientific consensus. As ever, the devil’s in the

detailsdefinitions, but while there is still discussion about how best to categorize the addiction, the scientific consensus as a whole is generally: sugar is addictive.That doesn’t mean scientists* are a hive mind, and so there will be some who disagree, but most papers these days are looking into the “hows” and “whys” and “whats” of sugar addiction, not the “whether”.

*who are also, let us remember, a diverse group including chemists, neurobiologists, psychologists, social psychologists, and others, often collaborating in multidisciplinary teams, each with their own focus of research.

Here’s what the Center of Alcohol and Substance Use Studies has to say, for example:

Sugar Addiction: More Serious Than You Think

Sugar is a chemical addiction, comparable to alcohol: True or False?

True, broadly, with caveats—for this one, the crux lies in “comparable to”, because the neurology of the addiction is similar, even if many aspects of it chemically are not.

In both cases, sugar triggers the release of dopamine while also (albeit for different chemical reasons) having a “downer” effect (sugar triggers the release of opioids as well as dopamine).

Notably, the sociology and psychology of alcohol and sugar addictions are also similar (both addictions are common throughout different socioeconomic strata as a coping mechanism seeking an escape from emotional pain).

See for example in the Journal of Psychoactive Drugs:

On the other hand, withdrawal symptoms from heavy long-term alcohol abuse can kill, while withdrawal symptoms from sugar are very much milder. So there’s also room to argue that they’re not comparable on those grounds.

Sugar is a chemical addiction, comparable to cocaine: True or False?

False, broadly. There are overlaps! For example, sugar drives impulsivity to seek more of the substance, and leads to changes in neurobiological brain function which alter emotional states and subsequent behaviours:

The impact of sugar consumption on stress driven, emotional and addictive behaviors

However!

Cocaine triggers a release of dopamine (as does sugar), but cocaine also acts directly on our brain’s ability to remove dopamine, serotonin, and norepinephrine:

The Neurobiology of Cocaine Addiction

…meaning that in terms of comparability, they (to use a metaphor now, not meaning this literally) both give you a warm feeling, but sugar does it by turning up the heating a bit whereas cocaine does it by locking the doors and burning down the house. That’s quite a difference!

Sugar is a behavioral addiction, comparable to video gaming: True or False?

True, with the caveat that this a “yes and” situation.

There are behavioral aspects of sugar addiction that can reasonably be compared to those of video gaming, e.g. compulsion loops, always the promise of more (without limiting factors such as overdosing), anxiety when the addictive element is not accessible for some reason, reduction of dopaminergic sensitivity leading to a craving for more, etc. Note that the last is mentioning a chemical but the mechanism itself is still behavioral, not chemical per se.

So, yes, it’s a behavioral addiction [and also arguably chemical in the manners we’ve described earlier in this article].

For science for this, we refer you back to:

The impact of sugar consumption on stress driven, emotional and addictive behaviors

Want more?

You might want to check out:

Beating Food Addictions: When It’s More Than “Just” Cravings

Take care!

Share This Post

Anti-Inflammatory Brownies

10almonds is reader-supported. We may, at no cost to you, receive a portion of sales if you purchase a product through a link in this article.

Brownies are usually full of sugar, butter, and flour. These ones aren’t! Instead, they’re full of fiber (good against inflammation), healthy fats, and anti-inflammatory polyphenols:

You will need

- 1 can chickpeas (keep half the chickpea water, also called aquafaba, as we’ll be using it)

- 4 oz of your favorite nut butter (substitute with tahini if you’re allergic to nuts)

- 3 oz rolled oats

- 2 oz dark chocolate chips (or if you want the best quality: dark chocolate, chopped into very small pieces)

- 3 tbsp of your preferred plant milk (this is an anti-inflammatory recipe and unfermented dairy is inflammatory)

- 2 tbsp cocoa powder (pure cacao is best)

- 1 tbsp glycine (if unavailable, use 2 tbsp maple syrup, and skip the aquafaba)

- 2 tsp vanilla extract

- ½ tsp baking powder

- ¼ tsp low-sodium salt

Method

(we suggest you read everything at least once before doing anything)

1) Preheat the oven to 350℉ / 180℃, and line a 7″ cake tin with baking paper.

2) Blend the oats in a food processor, until you have oat flour.

3) Add all the remaining ingredients except the dark chocolate chips, and process until the mixture resembles cookie dough.

3) Transfer to a bowl, and fold in the dark chocolate chips, distributing evenly.

4) Add the mixture to the cake tin, and smooth the surface down so that it’s flat and even. Bake for about 25 minutes, and let them cool in the tin for at least 10 minutes, but longer is better, as they will firm up while they cool. Cut into cubes when ready to serve:

Enjoy!

Want to learn more?

For those interested in some of the science of what we have going on today:

- Level-Up Your Fiber Intake! (Without Difficulty Or Discomfort)

- Cacao vs Carob – Which is Healthier?

- Keep Inflammation At Bay

- The Sweet Truth About Glycine

- The Best Kind Of Fiber For Overall Health?

Take care!

Share This Post

Sugar Blues – by William Dufty

10almonds is reader-supported. We may, at no cost to you, receive a portion of sales if you purchase a product through a link in this article.

This is a “read it cover to cover” book. It charts the rise of sugar’s place in world diets in general and the American diet in particular, and draws many conclusions about the effect this has had on us.

This book will challenge you. Sometimes, it will change your mind. Sometimes, you’ll go “no, I’m sure that’s not right”, and you’ll go Googling. Either way, you’ll learn something.

And that, for us, is the most important measure of any informational book: did we gain something from it? In Sugar Blues, perhaps the single biggest “gain” for the reader is that it’s an eye-opener and a call-to-arms—the extent to which you heed that is up to you, but it sure is good to at least be familiar with the battlefield.

Share This Post

Related Posts

WHO Overturns Dogma on Airborne Disease Spread. The CDC Might Not Act on It.

10almonds is reader-supported. We may, at no cost to you, receive a portion of sales if you purchase a product through a link in this article.

The World Health Organization has issued a report that transforms how the world understands respiratory infections like covid-19, influenza, and measles.

Motivated by grave missteps in the pandemic, the WHO convened about 50 experts in virology, epidemiology, aerosol science, and bioengineering, among other specialties, who spent two years poring through the evidence on how airborne viruses and bacteria spread.

However, the WHO report stops short of prescribing actions that governments, hospitals, and the public should take in response. It remains to be seen how the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention will act on this information in its own guidance for infection control in health care settings.

The WHO concluded that airborne transmission occurs as sick people exhale pathogens that remain suspended in the air, contained in tiny particles of saliva and mucus that are inhaled by others.

While it may seem obvious, and some researchers have pushed for this acknowledgment for more than a decade, an alternative dogma persisted — which kept health authorities from saying that covid was airborne for many months into the pandemic.

Specifically, they relied on a traditional notion that respiratory viruses spread mainly through droplets spewed out of an infected person’s nose or mouth. These droplets infect others by landing directly in their mouth, nose, or eyes — or they get carried into these orifices on droplet-contaminated fingers. Although these routes of transmission still happen, particularly among young children, experts have concluded that many respiratory infections spread as people simply breathe in virus-laden air.

“This is a complete U-turn,” said Julian Tang, a clinical virologist at the University of Leicester in the United Kingdom, who advised the WHO on the report. He also helped the agency create an online tool to assess the risk of airborne transmission indoors.

Peg Seminario, an occupational health and safety specialist in Bethesda, Maryland, welcomed the shift after years of resistance from health authorities. “The dogma that droplets are a major mode of transmission is the ‘flat Earth’ position now,” she said. “Hurray! We are finally recognizing that the world is round.”

The change puts fresh emphasis on the need to improve ventilation indoors and stockpile quality face masks before the next airborne disease explodes. Far from a remote possibility, measles is on the rise this year and the H5N1 bird flu is spreading among cattle in several states. Scientists worry that as the H5N1 virus spends more time in mammals, it could evolve to more easily infect people and spread among them through the air.

Traditional beliefs on droplet transmission help explain why the WHO and the CDC focused so acutely on hand-washing and surface-cleaning at the beginning of the pandemic. Such advice overwhelmed recommendations for N95 masks that filter out most virus-laden particles suspended in the air. Employers denied many health care workers access to N95s, insisting that only those routinely working within feet of covid patients needed them. More than 3,600 health care workers died in the first year of the pandemic, many due to a lack of protection.

However, a committee advising the CDC appears poised to brush aside the updated science when it comes to its pending guidance on health care facilities.

Lisa Brosseau, an aerosol expert and a consultant at the Center for Infectious Disease Research and Policy in Minnesota, warns of a repeat of 2020 if that happens.

“The rubber hits the road when you make decisions on how to protect people,” Brosseau said. “Aerosol scientists may see this report as a big win because they think everything will now follow from the science. But that’s not how this works and there are still major barriers.”

Money is one. If a respiratory disease spreads through inhalation, it means that people can lower their risk of infection indoors through sometimes costly methods to clean the air, such as mechanical ventilation and using air purifiers, and wearing an N95 mask. The CDC has so far been reluctant to press for such measures, as it updates foundational guidelines on curbing airborne infections in hospitals, nursing homes, prisons, and other facilities that provide health care. This year, a committee advising the CDC released a draft guidance that differs significantly from the WHO report.

Whereas the WHO report doesn’t characterize airborne viruses and bacteria as traveling short distances or long, the CDC draft maintains those traditional categories. It prescribes looser-fitting surgical masks rather than N95s for pathogens that “spread predominantly over short distances.” Surgical masks block far fewer airborne virus particles than N95s, which cost roughly 10 times as much.

Researchers and health care workers have been outraged about the committee’s draft, filing letters and petitions to the CDC. They say it gets the science wrong and endangers health. “A separation between short- and long-range distance is totally artificial,” Tang said.

Airborne viruses travel much like cigarette smoke, he explained. The scent will be strongest beside a smoker, but those farther away will inhale more and more smoke if they remain in the room, especially when there’s no ventilation.

Likewise, people open windows when they burn toast so that smoke dissipates before filling the kitchen and setting off an alarm. “You think viruses stop after 3 feet and drop to the ground?” Tang said of the classical notion of distance. “That is absurd.”

The CDC’s advisory committee is comprised primarily of infection control researchers at large hospital systems, while the WHO consulted a diverse group of scientists looking at many different types of studies. For example, one analysis examined the puff clouds expelled by singers, and musicians playing clarinets, French horns, saxophones, and trumpets. Another reviewed 16 investigations into covid outbreaks at restaurants, a gym, a food processing factory, and other venues, finding that insufficient ventilation probably made them worse than they would otherwise be.

In response to the outcry, the CDC returned the draft to its committee for review, asking it to reconsider its advice. Meetings from an expanded working group have since been held privately. But the National Nurses United union obtained notes of the conversations through a public records request to the agency. The records suggest a push for more lax protection. “It may be difficult as far as compliance is concerned to not have surgical masks as an option,” said one unidentified member, according to notes from the committee’s March 14 discussion. Another warned that “supply and compliance would be difficult.”

The nurses’ union, far from echoing such concerns, wrote on its website, “The Work Group has prioritized employer costs and profits (often under the umbrella of ‘feasibility’ and ‘flexibility’) over robust protections.” Jane Thomason, the union’s lead industrial hygienist, said the meeting records suggest the CDC group is working backward, molding its definitions of airborne transmission to fit the outcome it prefers.

Tang expects resistance to the WHO report. “Infection control people who have built their careers on this will object,” he said. “It takes a long time to change people’s way of thinking.”

The CDC declined to comment on how the WHO’s shift might influence its final policies on infection control in health facilities, which might not be completed this year. Creating policies to protect people from inhaling airborne viruses is complicated by the number of factors that influence how they spread indoors, such as ventilation, temperature, and the size of the space.

Adding to the complexity, policymakers must weigh the toll of various ailments, ranging from covid to colds to tuberculosis, against the burden of protection. And tolls often depend on context, such as whether an outbreak happens in a school or a cancer ward.

“What is the level of mortality that people will accept without precautions?” Tang said. “That’s another question.”

KFF Health News is a national newsroom that produces in-depth journalism about health issues and is one of the core operating programs at KFF—an independent source of health policy research, polling, and journalism. Learn more about KFF.

Subscribe to KFF Health News’ free Morning Briefing.

Don’t Forget…

Did you arrive here from our newsletter? Don’t forget to return to the email to continue learning!

Learn to Age Gracefully

Join the 98k+ American women taking control of their health & aging with our 100% free (and fun!) daily emails:

Cheeky diet soft drink getting you through the work day? Here’s what that may mean for your health

10almonds is reader-supported. We may, at no cost to you, receive a portion of sales if you purchase a product through a link in this article.

Many people are drinking less sugary soft drink than in the past. This is a great win for public health, given the recognised risks of diets high in sugar-sweetened drinks.

But over time, intake of diet soft drinks has grown. In fact, it’s so high that these products are now regularly detected in wastewater.

So what does the research say about how your health is affected in the long term if you drink them often?

Breakingpic/Pexels What makes diet soft drinks sweet?

The World Health Organization (WHO) advises people “reduce their daily intake of free sugars to less than 10% of their total energy intake. A further reduction to below 5% or roughly 25 grams (six teaspoons) per day would provide additional health benefits.”

But most regular soft drinks contain a lot of sugar. A regular 335 millilitre can of original Coca-Cola contains at least seven teaspoons of added sugar.

Diet soft drinks are designed to taste similar to regular soft drinks but without the sugar. Instead of sugar, diet soft drinks contain artificial or natural sweeteners. The artificial sweeteners include aspartame, saccharin and sucralose. The natural sweeteners include stevia and monk fruit extract, which come from plant sources.

Many artificial sweeteners are much sweeter than sugar so less is needed to provide the same burst of sweetness.

Diet soft drinks are marketed as healthier alternatives to regular soft drinks, particularly for people who want to reduce their sugar intake or manage their weight.

But while surveys of Australian adults and adolescents show most people understand the benefits of reducing their sugar intake, they often aren’t as aware about how diet drinks may affect health more broadly.

Diet soft drinks contain artificial or natural sweeteners. Vintage Tone/Shutterstock What does the research say about aspartame?

The artificial sweeteners in soft drinks are considered safe for consumption by food authorities, including in the US and Australia. However, some researchers have raised concern about the long-term risks of consumption.

People who drink diet soft drinks regularly and often are more likely to develop certain metabolic conditions (such as diabetes and heart disease) than those who don’t drink diet soft drinks.

The link was found even after accounting for other dietary and lifestyle factors (such as physical activity).

In 2023, the WHO announced reports had found aspartame – the main sweetener used in diet soft drinks – was “possibly carcinogenic to humans” (carcinogenic means cancer-causing).

Importantly though, the report noted there is not enough current scientific evidence to be truly confident aspartame may increase the risk of cancer and emphasised it’s safe to consume occasionally.

Will diet soft drinks help manage weight?

Despite the word “diet” in the name, diet soft drinks are not strongly linked with weight management.

In 2022, the WHO conducted a systematic review (where researchers look at all available evidence on a topic) on whether the use of artificial sweeteners is beneficial for weight management.

Overall, the randomised controlled trials they looked at suggested slightly more weight loss in people who used artificial sweeteners.

But the observational studies (where no intervention occurs and participants are monitored over time) found people who consume high amounts of artificial sweeteners tended to have an increased risk of higher body mass index and a 76% increased likelihood of having obesity.

In other words, artificial sweeteners may not directly help manage weight over the long term. This resulted in the WHO advising artificial sweeteners should not be used to manage weight.

Studies in animals have suggested consuming high levels of artificial sweeteners can signal to the brain it is being starved of fuel, which can lead to more eating. However, the evidence for this happening in humans is still unproven.

You can’t go wrong with water. hurricanehank/Shutterstock What about inflammation and dental issues?

There is some early evidence artificial sweeteners may irritate the lining of the digestive system, causing inflammation and increasing the likelihood of diarrhoea, constipation, bloating and other symptoms often associated with irritable bowel syndrome. However, this study noted more research is needed.

High amounts of diet soft drinks have also been linked with liver disease, which is based on inflammation.

The consumption of diet soft drinks is also associated with dental erosion.

Many soft drinks contain phosphoric and citric acid, which can damage your tooth enamel and contribute to dental erosion.

Moderation is key

As with many aspects of nutrition, moderation is key with diet soft drinks.

Drinking diet soft drinks occasionally is unlikely to harm your health, but frequent or excessive intake may increase health risks in the longer term.

Plain water, infused water, sparkling water, herbal teas or milks remain the best options for hydration.

Lauren Ball, Professor of Community Health and Wellbeing, The University of Queensland and Emily Burch, Accredited Practising Dietitian and Lecturer, Southern Cross University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Don’t Forget…

Did you arrive here from our newsletter? Don’t forget to return to the email to continue learning!

Learn to Age Gracefully

Join the 98k+ American women taking control of their health & aging with our 100% free (and fun!) daily emails:

Fatty Acids For The Eyes & Brain: The Good And The Bad

10almonds is reader-supported. We may, at no cost to you, receive a portion of sales if you purchase a product through a link in this article.

Good For The Eyes; Good For The Brain

We’ve written before about omega-3 fatty acids, covering the basics and some lesser-known things:

What Omega-3 Fatty Acids Really Do For Us

…and while we discussed its well-established benefits against cognitive decline (which is to be expected, because omega-3 is good against inflammation, and a large part of age-related neurodegeneration is heavily related to neuroinflammation), there’s a part of the brain we didn’t talk about in that article: the eyes.

We did, however, talk in another article about supplements that benefit the eyes and [the rest of the] brain, and the important links between the two, to the point that an examination of the levels of lutein in the retina can inform clinicians about the levels of lutein in the brain as a whole, and strongly predict Alzheimer’s disease (because Alzheimer’s patients have significantly less lutein), here:

Now, let’s tie these two ideas together

In a recent (June 2024) meta-analysis of high-quality observational studies from the US and around the world, involving nearly a quarter of a million people over 40 (n=241,151), researchers found that a higher intake of omega-3 is significantly linked to a lower risk of macular degeneration.

To put it in numbers, the highest intake of omega-3s was associated with an 18% reduced risk of early stage macular degeneration.

They also looked at a breakdown of what kinds of omega-3, and found that taking a blend DHA and EPA worked best of all, although of people who only took one kind, DHA was the best “single type” option.

You can read the paper in full, here:

Association between fatty acid intake and age-related macular degeneration: a meta-analysis

A word about trans-fatty acids (TFAs)

It was another feature of the same study that, while looking at fatty acids in general, they also found that higher consumption of trans-fatty acids was associated with a higher risk of advanced age-related macular degeneration.

Specifically, the highest intake of TFAs was associated with a more than 2x increased risk.

There are two main dietary sources of trans-fatty acids:

- Processed foods that were made with TFAs; these have now been banned in a lot of places, but only quite recently, and the ban is on the processing, not the sale, so if you buy processed foods that contain ingredients that were processed before 2021 (not uncommon, given the long life of many processed foods), the chances of them having TFAs is higher.

- Most animal products. Most notably from mammals and their milk, so beef, pork, lamb, milk, cheese, and yes even yogurt. Poultry and fish technically do also contain TFAs in most cases, but the levels are much lower.

Back to the omega-3 fatty acids…

If you’re wondering where to get good quality omega-3, well, we listed some of the best dietary sources in our main omega-3 article (linked at the top of today’s).

However, if you want to supplement, here’s an example product on Amazon that’s high in DHA and EPA, following the science of what we shared today 😎

Take care!

Don’t Forget…

Did you arrive here from our newsletter? Don’t forget to return to the email to continue learning!

Learn to Age Gracefully

Join the 98k+ American women taking control of their health & aging with our 100% free (and fun!) daily emails: