The “Five Tibetan Rites” & Why To Do Them!

10almonds is reader-supported. We may, at no cost to you, receive a portion of sales if you purchase a product through a link in this article.

Spinning Around

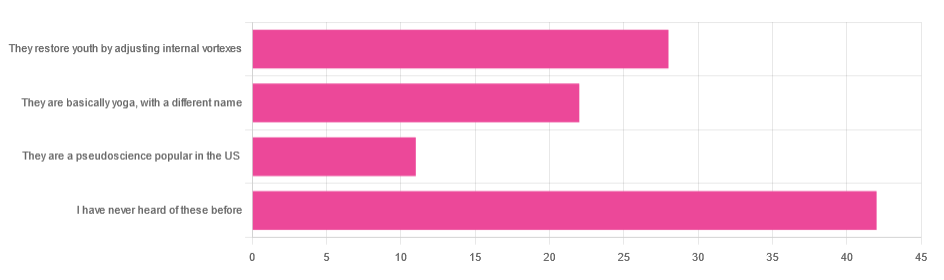

In Tuesday’s newsletter, we asked you for your opinion of the “Five Tibetan Rites”, and got the above-depicted, below-described, set of responses:

- About 41% said “I have never heard of these before”

- About 27% said “they restore youth by adjusting internal vortexes”

- About 22% said “they are basically yoga, by a different name”

- About 11% said “they are a pseudoscience popular in the US”

So what does the science say?

The Five Tibetan Rites are five Tibetan rites: True or False?

False, though this is more question of social science than of health science, so we’ll not count it against them for having a misleading name.

The first known mentioning of the “Five Tibetan Rites” is by an American named Peter Kelder, who in 1939 published, through a small LA occult-specialized publishing house, a booklet called “The Eye of Revelation”. This work was then varyingly republished, repackaged, and occasionally expanded upon by Kelder or other American authors, including Chris Kilham’s popular 1994 book “The Five Tibetans”.

The “Five Tibetan Rites” are unknown as such in Tibet, except for what awareness of them has been raised by people asking about them in the context of the American phenomenon.

Here’s a good history book, for those interested:

The author didn’t originally set out to “debunk” anything, and is himself a keen spiritualist (and practitioner of the five rites), but he was curious about the origins of the rites, and ultimately found them—as a collection of five rites, and the other assorted advices given by Kelder—to be an American synthesis in the whole, each part inspired by various different physical practices (some of them hatha yoga, some from the then-popular German gymnastics movement, some purely American spiritualism, all available in books that were popular in California in the early 1900s).

You may be wondering: why didn’t Kelder just say that, then, instead of telling stories of an ancient Tibetan tradition that empirically does not exist? The answer to this lies again in social science not health science, but it’s been argued that it’s common for Westerners to “pick ‘n’ mix” ideas from the East, champion them as inscrutably mystical, and (since they are inscrutable) then simply decide how to interpret and represent them. Here’s an excellent book on this, if you’re interested:

(in Kelder’s case, this meant that “there’s a Tibetan tradition, trust me” was thus more marketable in the West than “I read these books in LA”)

They are at least five rites: True or False?

True! If we use the broad definition of “rite” as “something done repeatedly in a solemn fashion”. And there are indeed five of them:

- Spinning around (good for balance)

- Leg raises (this one’s from German gymnastics)

- Kneeling back bend (various possible sources)

- Tabletop (hatha yoga, amongst others)

- Pendulum (hatha yoga, amongst others) ← you may recognize this one from the Sun Salutation

You can see them demonstrated here:

Click Here If The Embedded Video Doesn’t Load Automatically

Kelder also advocated for what was basically the Hay Diet (named not for the substance but for William Hay; it involved separating foods into acid and alkali, not necessarily according to the actual pH of the foods, and combining only “acid” foods or only “alkali” foods at a time), which was popular at the time, but has since been rejected as without scientific merit. Kelder referred to this as “the sixth rite”.

The Five Rites restore youth by adjusting internal vortexes: True or False?

False, in any scientific sense of that statement. Scientifically speaking, the body does not have vortexes to adjust, therefore that is not the mechanism of action.

Spiritually speaking, who knows? Not us, a humble health science publication.

The Five Rites are a pseudoscience popular in the US: True or False?

True, if 27% of those who responded of our mostly North American readership can be considered as representative of what is popular.

However…

“Pseudoscience” gets thrown around a lot as a bad word; it’s often used as a criticism, but it doesn’t have to be. Consider:

A small child who hears about “eating the rainbow” and mistakenly understands that we are all fuelled by internal rainbows that need powering-up by eating fruits and vegetables of different colors, and then does so…

…does not hold a remotely scientific view of how things are happening, but is nevertheless doing the correct thing as recommended by our best current science.

It’s thus a little similar with the five rites. Because…

The Five Rites are at least good for our health: True or False?

True! They are great for the health.

The first one (spinning around) is good for balance. Science would recommend doing it both ways rather than just one way, but one is not bad. It trains balance, trains our stabilizing muscles, and confuses our heart a bit (in a good way).

See also: Fall Special (How To Not Fall, And Not Get Injured If You Do)

The second one (leg raises) is excellent for core strength, which in turn helps keep our organs where they are supposed to be (this is a bigger health issue than most people realise, because “out of sight, out of mind”), which is beneficial for many aspects of our health!

See also: Visceral Belly Fat & How To Lose It ← visceral fat is the fat that surrounds your internal organs; too much there becomes a problem!

The third, fourth, and fifth ones stretch our spine (healthily), strengthen our back, and in the cases of the fourth and fifth ones, are good full-body exercises for building strength, and maintaining muscle mass and mobility.

See also: Building & Maintaining Mobility

So in short…

If you’ve been enjoying the Five Rites, by all means keep on doing them; they might not be Tibetan (or an ancient practice, as presented), and any mystical aspect is beyond the scope of our health science publication, but they are great for the health in science-based ways!

Take care!

Don’t Forget…

Did you arrive here from our newsletter? Don’t forget to return to the email to continue learning!

Recommended

Learn to Age Gracefully

Join the 98k+ American women taking control of their health & aging with our 100% free (and fun!) daily emails:

-

10 Lessons For A Healthy Mind & Body

10almonds is reader-supported. We may, at no cost to you, receive a portion of sales if you purchase a product through a link in this article.

Sadia Badiei, food scientist of “Pick Up Limes” culinary fame, has advice in and out of the kitchen:

Pick up a zest for life

Here’s what she picked up, and we all can too:

- “I can’t do it… yet”: it’s never too late to adopt a growth mindset by adding “yet” to your self-doubt, focusing on progress and the possibility of improvement.

- The spotlight effect: people are generally too absorbed in their own lives to focus on you, so don’t worry too much about others’ perceptions.

- Nutrition by addition: focus on adding healthier foods to your diet rather than eliminating the less healthy ones to avoid restrictive mindsets. You can still eliminate the less healthy ones if you want to! It just shouldn’t be the primary focus. Focusing on a conceptually negative thing is rarely helpful.

- It’s ok to change: embrace change as a sign of growth and evolution, rather than seeing it as a failure or waste of time.

- The way you do one thing is the way you do everything: be mindful of how you approach small tasks, regular tasks, boring tasks, unwanted tasks—you can either create a habit of enthusiasm or a habit of suffering (it’s entirely your choice which)

- Setting goals for success: set goals based on actions you can control (inputs) rather than outcomes that are uncertain. Less “lose 10 lbs”, and more “eat fiber before starch”, for example.

- You probably can’t have it all at once: you can achieve all your dreams, but often not simultaneously; goals and desires unfold in stages over time.

- The five-year rule: before adopting a new lifestyle or habit, ask yourself if you can realistically sustain it for five years to ensure it’s not just a short-term fix. If you struggle with this prognostic, look backwards first instead. Which healthy habits have you maintained for decades, and which were you never able to make stick?

- Are you afraid or excited?: reframe fear as excitement, as both emotions share similar physical sensations and signify that you care about the outcome.

- The voice you hear most: speak kindly to yourself in self-talk to create a softer, more compassionate tone. Your subconscious is always listening, so reinforce healthy rather than unhealthy thought patterns.

For more on each of these, enjoy:

Click Here If The Embedded Video Doesn’t Load Automatically!

Want to learn more?

You might also like to read:

80-Year-Olds Share Their Biggest Regrets

Take care!

Share This Post

-

Hospitals worldwide are short of saline. We can’t just switch to other IV fluids – here’s why

10almonds is reader-supported. We may, at no cost to you, receive a portion of sales if you purchase a product through a link in this article.

Last week, the Australian Therapeutic Goods Administration added intravenous (IV) fluids to the growing list of medicines in short supply. The shortage is due to higher-than-expected demand and manufacturing issues.

Two particular IV fluids are affected: saline and compound sodium lactate (also called Hartmann’s solution). Both fluids are made with salts.

There are IV fluids that use other components, such as sugar, rather than salt. But instead of switching patients to those fluids, the government has chosen to approve salt-based solutions by other overseas brands.

So why do IV fluids contain different chemicals? And why can’t they just be interchanged when one runs low?

Pavel Kosolapov/Shutterstock We can’t just inject water into a vein

Drugs are always injected into veins in a water-based solution. But we can’t do this with pure water, we need to add other chemicals. That’s because of a scientific principle called osmosis.

Osmosis occurs when water moves rapidly in and out of the cells in the blood stream, in response to changes to the concentration of chemicals dissolved in the blood plasma. Think salts, sugars, nutrients, drugs and proteins.

Too high a concentration of chemicals and protein in your blood stream leads it to being in a “hypertonic” state, which causes your blood cells to shrink. Not enough chemicals and proteins in your blood stream causes your blood cells to expand. Just the right amount is called “isotonic”.

Mixing the drug with the right amount of chemicals, via an injection or infusion, ensures the concentration inside the syringe or IV bag remains close to isotonic.

Australia is currently short on two salt-based IV fluids. sirnength88/Shutterstock What are the different types of IV fluids?

There are a range of IV fluids available to administer drugs. The two most popular are:

- 0.9% saline, which is an isotonic solution of table salt. This is one of the IV fluids in short supply

- a 5% solution of the sugar glucose/dextrose. This fluid is not in short supply.

There are also IV fluids that combine both saline and glucose, and IV fluids that have other salts:

- Ringer’s solution is an IV fluid which has sodium, potassium and calcium salts

- Plasma-Lyte has different sodium salts, as well as magnesium

- Hartmann’s solution (compound sodium lactate) contains a range of different salts. It is generally used to treat a condition called metabolic acidosis, where patients have increased acid in their blood stream. This is in short supply.

What if you use the wrong solution?

Some drugs are only stable in specific IV fluids, for instance, only in salt-based IV fluids or only in glucose.

Putting a drug into the wrong IV fluid can potentially cause the drug to “crash out” of the solution, meaning patients won’t get the full dose.

Or it could cause the drug to decompose: not only will it not work, but it could also cause serious side effects.

An example of where a drug can be transformed into something toxic is the cancer chemotherapy drug cisplatin. When administered in saline it is safe, but administration in pure glucose can cause life-threatening damage to a patients’ kidneys.

What can hospitals use instead?

The IV fluids in short supply are saline and Hartmann’s solution. They are provided by three approved Australian suppliers: Baxter Healthcare, B.Braun and Fresenius Kabi.

The government’s solution to this is to approve multiple overseas-registered alternative saline brands, which they are allowed to do under current legislation without it going through the normal Australian quality checks and approval process. They will have received approval in their country of manufacture.

The government is taking this approach because it may not be effective or safe to formulate medicines that are meant to be in saline into different IV fluids. And we don’t have sufficient capacity to manufacture saline IV fluids here in Australia.

The Australian Society of Hospital Pharmacists provides guidance to other health staff about what drugs have to go with which IV fluids in their Australian Injectable Drugs Handbook. If there is a shortage of saline or Hartmann’s solution, and shipments of other overseas brands have not arrived, this guidance can be used to select another appropriate IV fluid.

Why don’t we make it locally?

The current shortage of IV fluids is just another example of the problems Australia faces when it is almost completely reliant on its critical medicines from overseas manufacturers.

Fortunately, we have workarounds to address the current shortage. But Australia is likely to face ongoing shortages, not only for IV fluids but for any medicines that we rely on overseas manufacturers to produce. Shortages like this put Australian lives at risk.

In the past both myself, and others, have called for the federal government to develop or back the development of medicines manufacturing in Australia. This could involve manufacturing off-patent medicines with an emphasis on those medicines most used in Australia.

Not only would this create stable, high technology jobs in Australia, it would also contribute to our economy and make us less susceptible to future global drug supply problems.

Nial Wheate, Professor and Director Academic Excellence, Macquarie University and Shoohb Alassadi, Casual academic, pharmaceutical sciences, University of Sydney

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Share This Post

-

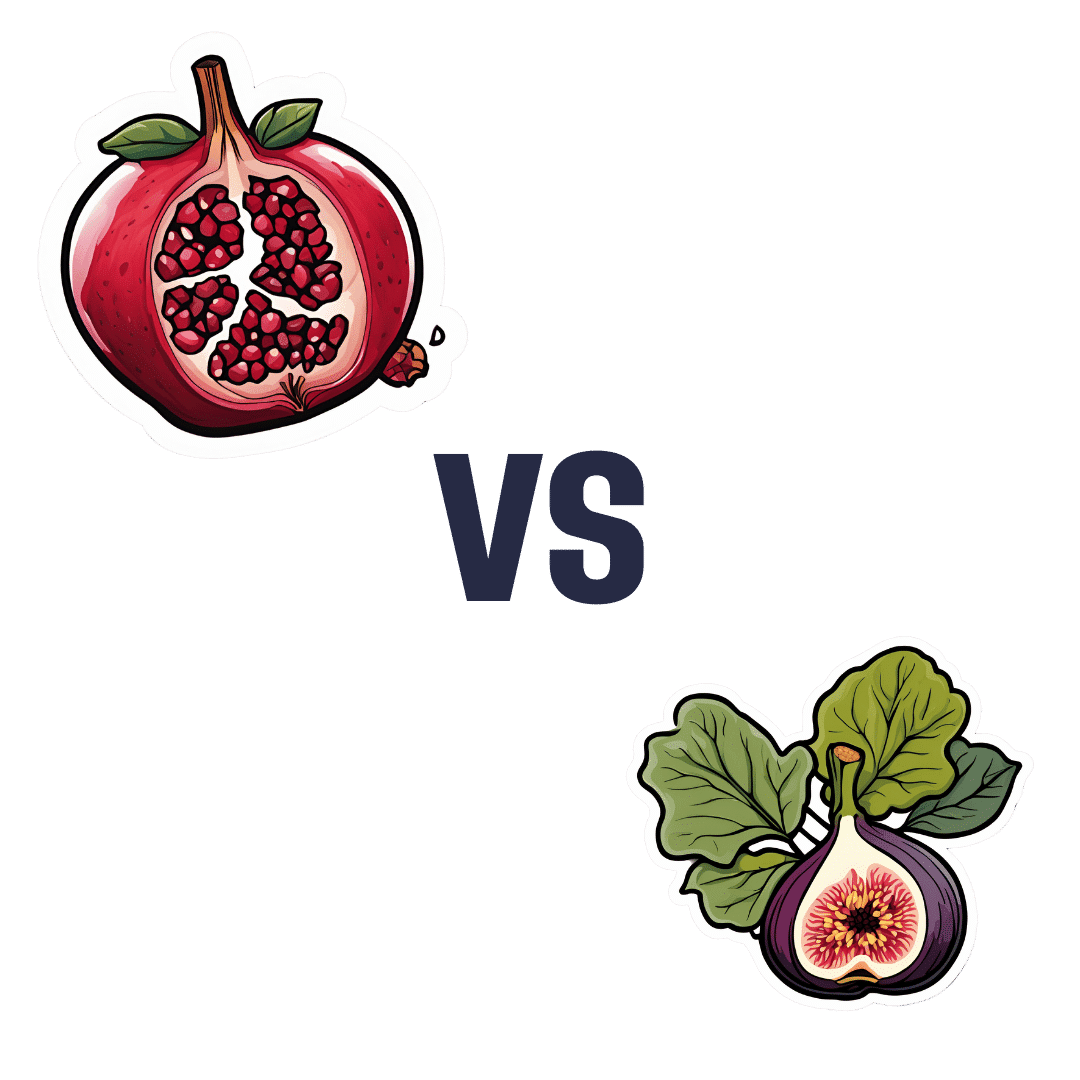

Pomegranate vs Figs – Which is Healthier?

10almonds is reader-supported. We may, at no cost to you, receive a portion of sales if you purchase a product through a link in this article.

Our Verdict

When comparing pomegranate to figs, we picked the pomegranate.

Why?

In terms of macros, pomegranate has a lot more protein* and fiber, while the fig has more carbs. Thus, a win for pomegranate.

*Why such protein in a fruit? In both cases, it’s mostly from the seeds, which in both cases, we’re eating. However, pomegranates have a much greater seed-to-mass ratio than figs, and thus, a correspondingly higher amount of protein. Also some fats from the seeds, again more than figs, but the margin of difference is smaller, and not really enough to be of relevance.

In the category of vitamins, pomegranates lead with more of vitamins B1, B5, B9, C, E, K, and choline, while figs have more of vitamins A, B3, and B6. The largest margins of difference are in vitamins B9, E, and K, so all in pomegranate’s favor.

The minerals scene is closer to even; pomegranate has more copper, phosphorus, potassium, selenium, and zinc, while figs have more calcium, iron, magnesium, and manganese. Thus, a 5:4 lead for pomegranate, and the larger margins of difference are again for pomegranate.

In short, enjoy both, but pomegranates are the more nutritionally dense. Also, don’t throw away the peel! Dry it, and turn it into a powdered supplement—see our linked article below, for why:

Want to learn more?

You might like to read:

Pomegranate’s Health Gifts Are Mostly In Its Peel

Take care!

Share This Post

Related Posts

-

Vaccines and cancer: The myth that won’t die

10almonds is reader-supported. We may, at no cost to you, receive a portion of sales if you purchase a product through a link in this article.

Two recent studies reported rising cancer rates among younger adults in the U.S. and worldwide. This prompted some online anti-vaccine accounts to link the studies’ findings to COVID-19 vaccines.

But, as with other myths, the data tells a very different story.

What you need to know

- Baseless claims that COVID-19 vaccines cause cancer have persisted online for several years and gained traction in late 2023.

- Two recent reports finding rising cancer rates among younger adults are based on pre-pandemic cancer incidence data. Cancer rates in the U.S. have been on the rise since the 1990s.

- There is no evidence of a link between COVID-19 vaccination and increased cancer risk.

False claims about COVID-19 vaccines began circulating months before the vaccines were available. Chief among these claims was misinformed speculation that vaccine mRNA could alter or integrate into vaccine recipients’ DNA.

It does not. But that didn’t prevent some on social media from spinning that claim into a persistent myth alleging that mRNA vaccines can cause or accelerate cancer growth. Anti-vaccine groups even coined the term “turbo cancer” to describe a fake phenomenon of abnormally aggressive cancers allegedly linked to COVID-19 vaccines.

They used the American Cancer Society’s 2024 cancer projection—based on incidence data through 2020—and a study of global cancer trends between 1999 and 2019 to bolster the false claims. This exposed the dishonesty at the heart of the anti-vaccine messaging, as data that predated the pandemic by decades was carelessly linked to COVID-19 vaccines in viral social media posts.

Some on social media cherry-pick data and use unfounded evidence because the claims that COVID-19 vaccines cause cancer are not true. According to the National Cancer Institute and American Cancer Society, there is no evidence of any link between COVID-19 vaccines and an increase in cancer diagnosis, progression, or remission.

Why does the vaccine cancer myth endure?

At the root of false cancer claims about COVID-19 vaccines is a long history of anti-vaccine figures falsely linking vaccines to cancer. Polio and HPV vaccines have both been the target of disproven cancer myths.

Not only do HPV vaccines not cause cancer, they are one of only two vaccines that prevent cancer.

In the case of polio vaccines, some early batches were contaminated with simian virus 40 (SV40), a virus that is known to cause cancer in some mammals but not humans. The contaminated batches were discovered, and no other vaccine has had SV40 contamination in over 60 years.

Follow-up studies found no increase in cancer rates in people who received the SV40-contaminated polio vaccine. Yet, vaccine opponents have for decades claimed that polio vaccines cause cancer.

Recycling of the SV40 myth

The SV40 myth resurfaced in 2023 when vaccine opponents claimed that COVID-19 vaccines contain the virus. In reality, a small, nonfunctional piece of the SV40 virus is used in the production of some COVID-19 vaccines. This DNA fragment, called the promoter, is commonly used in biomedical research and vaccine development and doesn’t remain in the finished product.

Crucially, the SV40 promoter used to produce COVID-19 vaccines doesn’t contain the part of the virus that enters the cell nucleus and is associated with cancer-causing properties in some animals. The promoter also lacks the ability to survive on its own inside the cell or interact with DNA. In other words, it poses no risk to humans.

Over 5.6 billion people worldwide have received COVID-19 vaccines since December 2020. At that scale, even the tiniest increase in cancer rates in vaccinated populations would equal hundreds of thousands of excess cancer diagnoses and deaths. The evidence for alleged vaccine-linked cancer would be observed in real incidence, treatment, and mortality data, not social media anecdotes or unverifiable reports.

This article first appeared on Public Good News and is republished here under a Creative Commons license.

Don’t Forget…

Did you arrive here from our newsletter? Don’t forget to return to the email to continue learning!

Learn to Age Gracefully

Join the 98k+ American women taking control of their health & aging with our 100% free (and fun!) daily emails:

-

Long COVID is real—here’s how patients can get treatment and support

10almonds is reader-supported. We may, at no cost to you, receive a portion of sales if you purchase a product through a link in this article.

What you need to know

- There is still no single, FDA-approved treatment for long COVID, but doctors can help patients manage individual symptoms.

- Long COVID patients may be eligible for government benefits that can ease financial burdens.

- Getting reinfected with COVID-19 can worsen existing long COVID symptoms, but patients can take steps to stay protected.

On March 15—Long COVID Awareness Day—patients shared their stories and demanded more funding for long COVID research. Nearly one in five U.S. adults who contract COVID-19 suffer from long COVID, and up to 5.8 million children have the disease.

Anyone who contracts COVID-19 is at risk of developing long-term illness. Long COVID has been deemed by some a “mass-disabling event,” as its symptoms can significantly disrupt patients’ lives.

Fortunately, there’s hope. New treatment options are in development, and there are resources available that may ease the physical, mental, and financial burdens that long COVID patients face.

Read on to learn more about resources for long COVID patients and how you can support the long COVID patients in your life.

What is long COVID, and who is at risk?

Long COVID is a cluster of symptoms that can occur after a COVID-19 infection and last for weeks, months, or years, potentially affecting almost every organ. Symptoms range from mild to debilitating and may include fatigue, chest pain, brain fog, dizziness, abdominal pain, joint pain, and changes in taste or smell.

Anyone who gets infected with COVID-19 is at risk of developing long COVID, but some groups are at greater risk, including unvaccinated people, women, people over 40, and people who face health inequities.

What types of support are available for long COVID patients?

Currently, there is still no single, FDA-approved treatment for long COVID, but doctors can help patients manage individual symptoms. Some options for long COVID treatment include therapies to improve lung function and retrain your sense of smell, as well as medications for pain and blood pressure regulation. Staying up to date on COVID-19 vaccines may also improve symptoms and reduce inflammation.

Long COVID patients are eligible for disability benefits under the Americans with Disabilities Act. The Pandemic Legal Assistance Network provides pro bono support for long COVID patients applying for these benefits.

Long COVID patients may also be eligible for other forms of government assistance, such as Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP), Temporary Assistance for Needy Families (TANF), Medicaid, and rental and utility assistance programs.

How can friends and family of long COVID patients provide support?

Getting reinfected with COVID-19 can worsen existing long COVID symptoms. Wearing a high-quality, well-fitting mask will reduce your risk of contracting COVID-19 and spreading it to long COVID patients and others. At indoor gatherings, improving ventilation by opening doors and windows, using high-efficiency particulate air (HEPA) filters, and building your own Corsi-Rosenthal box can also reduce the spread of the COVID-19 virus.

Long COVID patients may also benefit from emotional and financial support as they manage symptoms, navigate barriers to treatment, and go through the months-long process of applying for and receiving disability benefits.

For more information, talk to your health care provider.

This article first appeared on Public Good News and is republished here under a Creative Commons license.

Don’t Forget…

Did you arrive here from our newsletter? Don’t forget to return to the email to continue learning!

Learn to Age Gracefully

Join the 98k+ American women taking control of their health & aging with our 100% free (and fun!) daily emails:

-

The Intelligence Trap – by David Robson

10almonds is reader-supported. We may, at no cost to you, receive a portion of sales if you purchase a product through a link in this article.

We’re including this one under the umbrella of “general wellness”, because it happens that a lot of very intelligent people make stunningly unfortunate choices sometimes, for reasons that may baffle others.

The author outlines for us the various reasons that this happens, and how. From the famous trope of “specialized intelligence in one area”, to the tendency of people who are better at acquiring knowledge and understanding to also be better at acquiring biases along the way, to the hubris of “I am intelligent and therefore right as a matter of principle” thinking, and many other reasons.

Perhaps the greatest value of the book is the focus on how we can avoid these traps, narrow our bias blind spots, and play to our strengths while paying full attention to our weaknesses.

The style is very readable, despite having a lot of complex ideas discussed along the way. This is entirely to be expected of this author, an award-winning science writer.

Bottom line: if you’d like to better understand the array of traps that disproportionately catch out the most intelligent people (and how to spot such), then this is a great book for you.

Click here to check out The Intelligence Trap, and be more wary!

Don’t Forget…

Did you arrive here from our newsletter? Don’t forget to return to the email to continue learning!

Learn to Age Gracefully

Join the 98k+ American women taking control of their health & aging with our 100% free (and fun!) daily emails: