I want to eat healthily. So why do I crave sugar, salt and carbs?

10almonds is reader-supported. We may, at no cost to you, receive a portion of sales if you purchase a product through a link in this article.

We all want to eat healthily, especially as we reset our health goals at the start of a new year. But sometimes these plans are sabotaged by powerful cravings for sweet, salty or carb-heavy foods.

So why do you crave these foods when you’re trying to improve your diet or lose weight? And what can you do about it?

There are many reasons for craving specific foods, but let’s focus on four common ones:

1. Blood sugar crashes

Sugar is a key energy source for all animals, and its taste is one of the most basic sensory experiences. Even without specific sweet taste receptors on the tongue, a strong preference for sugar can develop, indicating a mechanism beyond taste alone.

Neurons responding to sugar are activated when sugar is delivered to the gut. This can increase appetite and make you want to consume more. Giving into cravings also drives an appetite for more sugar.

In the long term, research suggests a high-sugar diet can affect mood, digestion and inflammation in the gut.

While there’s a lot of variation between individuals, regularly eating sugary and high-carb foods can lead to rapid spikes and crashes in blood sugar levels. When your blood sugar drops, your body can respond by craving quick sources of energy, often in the form of sugar and carbs because these deliver the fastest, most easily accessible form of energy.

2. Drops in dopamine and serotonin

Certain neurotransmitters, such as dopamine, are involved in the reward and pleasure centres of the brain. Eating sugary and carb-rich foods can trigger the release of dopamine, creating a pleasurable experience and reinforcing the craving.

Serotonin, the feel-good hormone, suppresses appetite. Natural changes in serotonin can influence daily fluctuations in mood, energy levels and attention. It’s also associated with eating more carb-rich snacks in the afternoon.

Marcus Aurelius/Pexels

Low carb diets may reduce serotonin and lower mood. However, a recent systematic review suggests little association between these diets and risk for anxiety and depression.

Compared to men, women tend to crave more carb rich foods. Feeling irritable, tired, depressed or experiencing carb cravings are part of premenstrual symptoms and could be linked to reduced serotonin levels.

3. Loss of fluids and drops in blood sugar and salt

Sometimes our bodies crave the things they’re missing, such as hydration or even salt. A low-carb diet, for example, depletes insulin levels, decreasing sodium and water retention.

Very low-carb diets, like ketogenic diets, induce “ketosis”, a metabolic state where the body switches to using fat as its primary energy source, moving away from the usual dependence on carbohydrates.

Ketosis is often associated with increased urine production, further contributing to potential fluid loss, electrolyte imbalances and salt cravings.

4. High levels of stress or emotional turmoil

Stress, boredom and emotional turmoil can lead to cravings for comfort foods. This is because stress-related hormones can impact our appetite, satiety (feeling full) and food preferences.

The stress hormone cortisol, in particular, can drive cravings for sweet comfort foods.

A 2001 study of 59 premenopausal women subjected to stress revealed that the stress led to higher calorie consumption.

A more recent study found chronic stress, when paired with high-calorie diet, increases food intake and a preference for sweet foods. This shows the importance of a healthy diet during stress to prevent weight gain.

What can you do about cravings?

Here are four tips to curb cravings:

1) don’t cut out whole food groups. Aim for a well-balanced diet and make sure you include:

- sufficient protein in your meals to help you feel full and reduce the urge to snack on sugary and carb-rich foods. Older adults should aim for 20–40g protein per meal with a particular focus on breakfast and lunch and an overall daily protein intake of at least 0.8g per kg of body weight for muscle health

- fibre-rich foods, such as vegetables and whole grains. These make you feel full and stabilise your blood sugar levels. Examples include broccoli, quinoa, brown rice, oats, beans, lentils and bran cereals. Substitute refined carbs high in sugar like processed snack bars, soft drink or baked goods for more complex ones like whole grain bread or wholewheat muffins, or nut and seed bars or energy bites made with chia seeds and oats

2) manage your stress levels. Practise stress-reduction techniques like meditation, deep breathing, or yoga to manage emotional triggers for cravings. Practising mindful eating, by eating slowly and tuning into bodily sensations, can also reduce daily calorie intake and curb cravings and stress-driven eating

3) get enough sleep. Aim for seven to eight hours of quality sleep per night, with a minimum of seven hours. Lack of sleep can disrupt hormones that regulate hunger and cravings

4) control your portions. If you decide to indulge in a treat, control your portion size to avoid overindulging.

Overcoming cravings for sugar, salt and carbs when trying to eat healthily or lose weight is undoubtedly a formidable challenge. Remember, it’s a journey, and setbacks may occur. Be patient with yourself – your success is not defined by occasional cravings but by your ability to manage and overcome them.

Hayley O’Neill, Assistant Professor, Faculty of Health Sciences and Medicine, Bond University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Don’t Forget…

Did you arrive here from our newsletter? Don’t forget to return to the email to continue learning!

Recommended

Learn to Age Gracefully

Join the 98k+ American women taking control of their health & aging with our 100% free (and fun!) daily emails:

-

Exercise with Type 1 Diabetes – by Ginger Vieira

10almonds is reader-supported. We may, at no cost to you, receive a portion of sales if you purchase a product through a link in this article.

If you or a loved one has Type 1 Diabetes, you’ll know that exercise can be especially frustrating…

- If you don’t do it, you risk weight gain and eventual insulin resistance.

- If you do it, you risk dangerous hypos, or perhaps hypers if you took off your pump or skipped a bolus.

Unfortunately, the popular medical advice is “well, just do your best”.

Ginger Vieira is Type 1 Diabetic, and writes with 20+ experience of managing her diabetes while being a keen exerciser. As T1D folks out there will also know, comorbidities are very common; in her case, fibromyalgia was the biggest additional blow to her ability to exercise, along with an underactive thyroid. So when it comes to dealing with the practical nuts and bolts of things, she (while herself observing she’s not a doctor, let alone your doctor) has a lot more practical knowledge than an endocrinologist (without diabetes) behind a desk.

Speaking of nuts and bolts, this book isn’t a pep talk.

It has a bit of that in, but most of it is really practical information, e.g: using fasted exercise (4 hours from last meal+bolus) to prevent hypos, counterintuitive as that may seem—the key is that timing a workout for when you have the least amount of fast-acting insulin in your body means your body can’t easily use your blood sugars for energy, and draws from your fat reserves instead… Win/Win!

That’s just one quick tip because this is a 1-minute review, but Vieira gives:

- whole chapters, with example datasets (real numbers)

- tech-specific advice, e.g. pump, injection, etc

- insulin-specific advice, e.g. fast vs slow, and adjustments to each in the context of exercise

- timing advice re meal/bolus/exercise for different insulins and techs

- blood-sugar management advice for different exercise types (aerobic/anaerobic, sprint/endurance, etc)

…and lots more that we don’t have room to mention here

Basically… If you or a loved one has T1D, we really recommend this book!

Order a copy of “Exercise with Type 1 Diabetes” from Amazon today!

Share This Post

-

What will aged care look like for the next generation? More of the same but higher out-of-pocket costs

10almonds is reader-supported. We may, at no cost to you, receive a portion of sales if you purchase a product through a link in this article.

Aged care financing is a vexed problem for the Australian government. It is already underfunded for the quality the community expects, and costs will increase dramatically. There are also significant concerns about the complexity of the system.

In 2021–22 the federal government spent A$25 billion on aged services for around 1.2 million people aged 65 and over. Around 60% went to residential care (190,000 people) and one-third to home care (one million people).

The final report from the government’s Aged Care Taskforce, which has been reviewing funding options, estimates the number of people who will need services is likely to grow to more than two million over the next 20 years. Costs are therefore likely to more than double.

The taskforce has considered what aged care services are reasonable and necessary and made recommendations to the government about how they can be paid for. This includes getting aged care users to pay for more of their care.

But rather than recommending an alternative financing arrangement that will safeguard Australians’ aged care services into the future, the taskforce largely recommends tidying up existing arrangements and keeping the status quo.

No Medicare-style levy

The taskforce rejected the aged care royal commission’s recommendation to introduce a levy to meet aged care cost increases. A 1% levy, similar to the Medicare levy, could have raised around $8 billion a year.

The taskforce failed to consider the mix of taxation, personal contributions and social insurance which are commonly used to fund aged care systems internationally. The Japanese system, for example, is financed by long-term insurance paid by those aged 40 and over, plus general taxation and a small copayment.

Instead, the taskforce puts forward a simple, pragmatic argument that older people are becoming wealthier through superannuation, there is a cost of living crisis for younger people and therefore older people should be required to pay more of their aged care costs.

Separating care from other services

In deciding what older people should pay more for, the taskforce divided services into care, everyday living and accommodation.

The taskforce thought the most important services were clinical services (including nursing and allied health) and these should be the main responsibility of government funding. Personal care, including showering and dressing were seen as a middle tier that is likely to attract some co-payment, despite these services often being necessary to maintain independence.

The task force recommended the costs for everyday living (such as food and utilities) and accommodation expenses (such as rent) should increasingly be a personal responsibility.

Aged care users will pay more of their share for cooking and cleaning.

Lizelle Lotter/ShutterstockMaking the system fairer

The taskforce thought it was unfair people in residential care were making substantial contributions for their everyday living expenses (about 25%) and those receiving home care weren’t (about 5%). This is, in part, because home care has always had a muddled set of rules about user co-payments.

But the taskforce provided no analysis of accommodation costs (such as utilities and maintenance) people meet at home compared with residential care.

To address the inefficiencies of upfront daily fees for packages, the taskforce recommends means testing co-payments for home care packages and basing them on the actual level of service users receive for everyday support (for food, cleaning, and so on) and to a lesser extent for support to maintain independence.

It is unclear whether clinical and personal care costs and user contributions will be treated the same for residential and home care.

Making residential aged care sustainable

The taskforce was concerned residential care operators were losing $4 per resident day on “hotel” (accommodation services) and everyday living costs.

The taskforce recommends means tested user contributions for room services and everyday living costs be increased.

It also recommends that wealthier older people be given more choice by allowing them to pay more (per resident day) for better amenities. This would allow providers to fully meet the cost of these services.

Effectively, this means daily living charges for residents are too low and inflexible and that fees would go up, although the taskforce was clear that low-income residents should be protected.

Moving from buying to renting rooms

Currently older people who need residential care have a choice of making a refundable up-front payment for their room or to pay rent to offset the loans providers take out to build facilities. Providers raise capital to build aged care facilities through equity or loan financing.

However, the taskforce did not consider the overall efficiency of the private capital market for financing aged care or alternative solutions.

Instead, it recommended capital contributions be streamlined and simplified by phasing out up-front payments and focusing on rental contributions. This echoes the royal commission, which found rent to be a more efficient and less risky method of financing capital for aged care in private capital markets.

It’s likely that in a decade or so, once the new home care arrangements are in place, there will be proportionally fewer older people in residential aged care. Those who do go are likely to be more disabled and have greater care needs. And those with more money will pay more for their accommodation and everyday living arrangements. But they may have more choice too.

Although the federal government has ruled out an aged care levy and changes to assets test on the family home, it has yet to respond to the majority of the recommendations. But given the aged care minister chaired the taskforce, it’s likely to provide a good indication of current thinking.

Hal Swerissen, Emeritus Professor, La Trobe University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Share This Post

-

How To Out-Cheat “Cheat Days”

10almonds is reader-supported. We may, at no cost to you, receive a portion of sales if you purchase a product through a link in this article.

Out-Cheating “Cheat Days” (Or Even Just “Cheat Meals”)

If you are in the habit of eating healthily, the idea of a “cheat day” probably isn’t appealing—because you simply don’t crave junk food; it’s not what your gut is used to.

Nevertheless, sometimes cheat days, or at least cheat meals, choose us rather than the other way around. If your social group is having a pizza night or meeting up at the burger bar, probably you’re going to be having a meal that’s not ideal.

So, what to do about it?

Well, first of all, relax. If it really is an exception and not a regular occurrence, it’s not going to have a big health impact. Assuming that your basic dietary requirements are taken care of (e.g. free from allergens as necessary, vegan/vegetarian if that’s appropriate for you, adhering to any religious restrictions that are important to you, etc), then you’re going to have a good time, which is what scientists call a “pro-social activity” and is not a terrible thing.

See also: Is Fast Food Really All That Bad? ← answer: yes it is, but the harm is cumulative and won’t all happen the instant you take a bite of a chicken nugget

Think positive

No, not in the “think positive thoughts” sense (though feel free, if that’s your thing), but rather: focus on adding things rather than subtracting things.

It’s said:

❝It’s not the calories in your food that make the biggest impact on your health; it’s the food in your calories❞e

…and that’s generally true. The same goes for “bad things” in the food, e.g. added sugar, salt, seed oils, etc. They really are bad! But, in this case you’re going to be eating them and they’re going to be nearly impossible to avoid in the social scenarios we described. So, forget that sunk treasure, and instead, add nutrients.

10almonds tip: added nutrients remain added nutrients, even if the sources were not glowing with health-appeal and/or you ate them alongside something unhealthy:

- Those breaded garlic mushrooms are still full of magnesium and fiber and ergothioneine.

- The chili-and-mint peas that came as an overpriced optional side-dish with your burger are still full of protein, fiber, and a stack of polyphenols.

…and so on. And, the more time you spend eating those things, the less time you spend eating the real empty-calorie foods.

Fix the flaw

We set out to offer this guide without arguing for abstemiousness or making healthy substitutions, because we assume you knew already that you can not eat things, and as for substitutions, often they are not practical, especially if dining out or ordering in.

Also, sometimes even when home-cooking something unhealthy, taking the bad ingredient out takes some of the joy out with it.

Writers example: I once incorrectly tried to solve the fat conundrum of my favorite shchi (recipe here) by trying purely steaming the vegetables instead of my usual frying/sautéing them, and let’s just say, that errant-and-swiftly-abandoned version got recorded in my nutrition-tracker app as “sad shchi”.

So instead, fix the flaw by countering it if possible:

- The meal is devoid of fiber? Preload with some dried figs (you can never have too many dried figs in your pantry)

- The meal is high in saturated fat? Enjoy fiber before/during/after, per what’s convenient for you. Fiber helps clear out excess cholesterol, which is usually the main issue with saturated fat.

- The meal is salty? Double down on your hydration before, during, and after. If that sounds like a chore, then remember, it’s more fun than getting bloated (which results, counterintuitively, from dehydration—because your body detects the salt, and panics and tries to retain as much water as possible to restore homeostasis, resulting in bloating) and hypertensive (which results from the combination of the blood having too much salt and too little water, and cells retaining too much water and pressing inwards because it is the cells themselves that are bloated). So, tending to your hydration can help mitigate all of the above.

- The meal is full of high-GI carbs? Preload with fiber, enjoy the carbs together with fats, and have something acidic (e.g. some kind of vinegar, or citrus fruit) with it if that’s a reasonable option. Yes, this does mean that a Whiskey Sour is better for your blood sugars than an Old Fashioned, by the way, and/but no, it doesn’t make either of them healthy.

- The meal is inflammatory? Doing all of the above things will help, as will eating it slowly/mindfully, which latter makes it less of a shock to your system.

See also: How To Get More Nutrition From The Same Food

Enjoy!

Share This Post

Related Posts

-

Vegetarian & Vegan Diets: Good Or Bad For Brain Health?

10almonds is reader-supported. We may, at no cost to you, receive a portion of sales if you purchase a product through a link in this article.

It’s well-established that most people should eat more plants, and generally speaking, less meat. But what about abstaining from meat completely? And what about abstaining from all animal products?

For a more general overview (rather than specifically brain health), check out: Do We Need Animal Products To Be Healthy?

Now, about brains…

Before Homo sapiens was a thing, our precursors such as Homo habilis developed language (thus: greatly enhanced collaborative teamwork) and cooking, resulting in Homo ergaster (who came approximately next in line, give or take taxonomical quibbles) having twice the cranial capacity, generally attributed to being able to acquire and—where appropriate—cook calorie-dense food, which included meat, and also tubers that can’t be safely eaten raw. It’s estimated (based on forensic examination of tooth wear, mineralization, microdeposits of various kinds, etc) that our consumption of animal products in that era was around 10% of our diet (fluctuating by region, of course), but it likely was an important one.

By the time we got to Homo erectus, our skulls (including our cranial cavities, and thus it is presumed, our brains) were actually larger than in Homo sapiens. You may be wondering about Homo neanderthalensis; our cousins (or in some cases, ancestors—but that is beyond the scope of today’s article) also had larger cranial cavities than us, and certainly enjoyed comparatively advanced culture, arts, religion, etc.

Fast-forward to the present day. Nothing is going to meaningfully change our skull size, as individuals. Brain size? Well, keep hydrated or it’ll shrink. Don’t overhydrate or it’ll swell. Neuroplasticity means we can increase (or lose) volume in specific areas of the brain, according to what we do most of. For example, if you were to scan this writer’s brain, you’d probably find overdevelopment in the various areas pertaining to language and memory, as that’s been “my thing” for as long as I can remember (which is a long way). See also: An Underrated Tool Against Alzheimer’s

The impact of diet in the modern day

Unlike our distant ancestors, if we want a high-calorie snack we can buy some nuts from the supermarket, and if anything, this can be a problem (as many people’s go-to high-calorie snack may be a lot less healthy than that), and in turn cause problems for the brain, because too many pizzas, cheeseburgers, tater tots, and so forth cause chronic inflammation, and thus, neuroinflammation.

See also: 6 Worst Foods That Cause Dementia

So much for “calories for the brain”. Yes, the brain definitely needs calories (it expends a very large portion of our daily calorie intake), but you can have too much of a good thing.

In any case, the brain needs more than just calories!

For example, you may remember the “6 Pillars Of Nutritional Psychiatry”, which are:

- Be whole; eat whole

- Eat the rainbow

- The greener, the better

- Tap into your body intelligence

- Consistency & balance are key

- Avoid anxiety-triggering foods

For more on all of those, see Dr. Uma Naidoo’s 6 Pillars Of Nutritional Psychiatry ← She’s a Harvard-trained psychiatrist, professional chef graduating with her culinary school’s most coveted award, and a trained nutritionist. Between those three qualifications, she knows her stuff when it comes to the niche that is nutritional psychiatry.

When it comes to any potential nutritional deficiencies of a vegetarian or vegan diet, it’s a matter of planning.

Properly planned vegetarian diets are rich in essential nutrients like carbohydrates, fiber, magnesium, potassium, folate, vitamins C and E, and an abundance of phytochemicals, which support brain health (and overall health too, but today is about brain health).

However, if not well-planned, they can indeed lack certain nutrients such as vitamin B12, iron, and omega-3 fatty acids, which are critical for brain function.

In essence, there’s a difference between a “whole foods plant-based diet” and junk food that just happens to be vegetarian or vegan.

Vitamin B12 is usually supplemented by vegans, but it can also be enjoyed from nutritional yeast used in cooking (it adds a cheesy flavor to dishes for which that’d be appropriate).

Iron is a fascinating beast, because while everyone thinks of red meat (which is indeed rich in iron), not only are there good plant-based sources of iron, but there are important considerations when it comes to bioavailability differences between heme and non-heme iron. In few words, heme iron (from blood etc) is more bioavailable by 1.8x, but all iron, including non-heme iron (from beans, greens, etc) can have its bioavailability multiplied by 5x just by having it with vitamin C:

Avoiding Anemia (More Than Just “Get More Iron”)

Omega-3 fatty acids, for vegetarians that mostly means eggs. See: Eggs: All Things In Moderation?

For vegans, we must look to nuts and seeds, for the most part. Or supplement—many omega 3 supplements are vegan, made from algae, or seaweed (that in turn is composed partially or entirely of algae):

So really, it comes down to “make sure you still get these things”, and once you’re used to it, it’s easy.

For those who prefer to keep some meat in their diet

Our summary in our top-linked article (Do We Need Animal Products To Be Healthy?) concluded:

- Most of us can live healthily and happily on just plants if we so choose.

- Some people cannot, and will require varying kinds (and quantities) of animal products.

- As for red and/or processed meats, we’re not the boss of you, but from a health perspective, the science is clear: unless you have a circumstance that really necessitates it, just don’t.

- Same goes for pork, which isn’t red and may not be processed, but metabolically it’s associated with the same problems.

- The jury is out on poultry, but it strongly appears to be optional, healthwise, without making much of a difference either way

- Fish is roundly considered healthful in moderation. Enjoy it if you want, don’t if you don’t.

And the paper from which we’ve largely been working from today included such comments as:

❝ Evidence suggests that vegan and vegetarian diets, when well planned, can be rich in phytonutrients and antioxidants, which have been associated with lower levels of inflammatory markers, such as C-reactive protein (CRP) and interleukin-6 (IL-6). These findings indicate a potential role in reducing systemic inflammation and oxidative stress, both of which are linked to neurodegenerative diseases.

However, deficiencies in critical nutrients such as vitamin B12, DHA, EPA, and iron have been consistently associated with an increased risk of cognitive decline, mood disturbances, and neurodegenerative disorders.

While plant-based diets provide anti-inflammatory and antioxidant benefits, their neurological implications depend on nutrient adequacy. Proper planning, supplementation, and food preparation techniques are essential to mitigate risks and enhance cognitive health.❞

Source: Impact of Vegan and Vegetarian Diets on Neurological Health: A Critical Review ← you can see that they also cover the same nutrients that we do

One final note, not discussed above

We often say “what’s good for your heart is good for your brain”, because the former feeds the latter (with oxygen and nutrients) and assists in cleanup (of detritus that otherwise brings about cognitive decline).

So with that in mind…

What Matters Most For Your Heart? ← hint: it’s fiber. So whether you eat animal products or not, please do eat plenty of plants!

Take care!

Don’t Forget…

Did you arrive here from our newsletter? Don’t forget to return to the email to continue learning!

Learn to Age Gracefully

Join the 98k+ American women taking control of their health & aging with our 100% free (and fun!) daily emails:

-

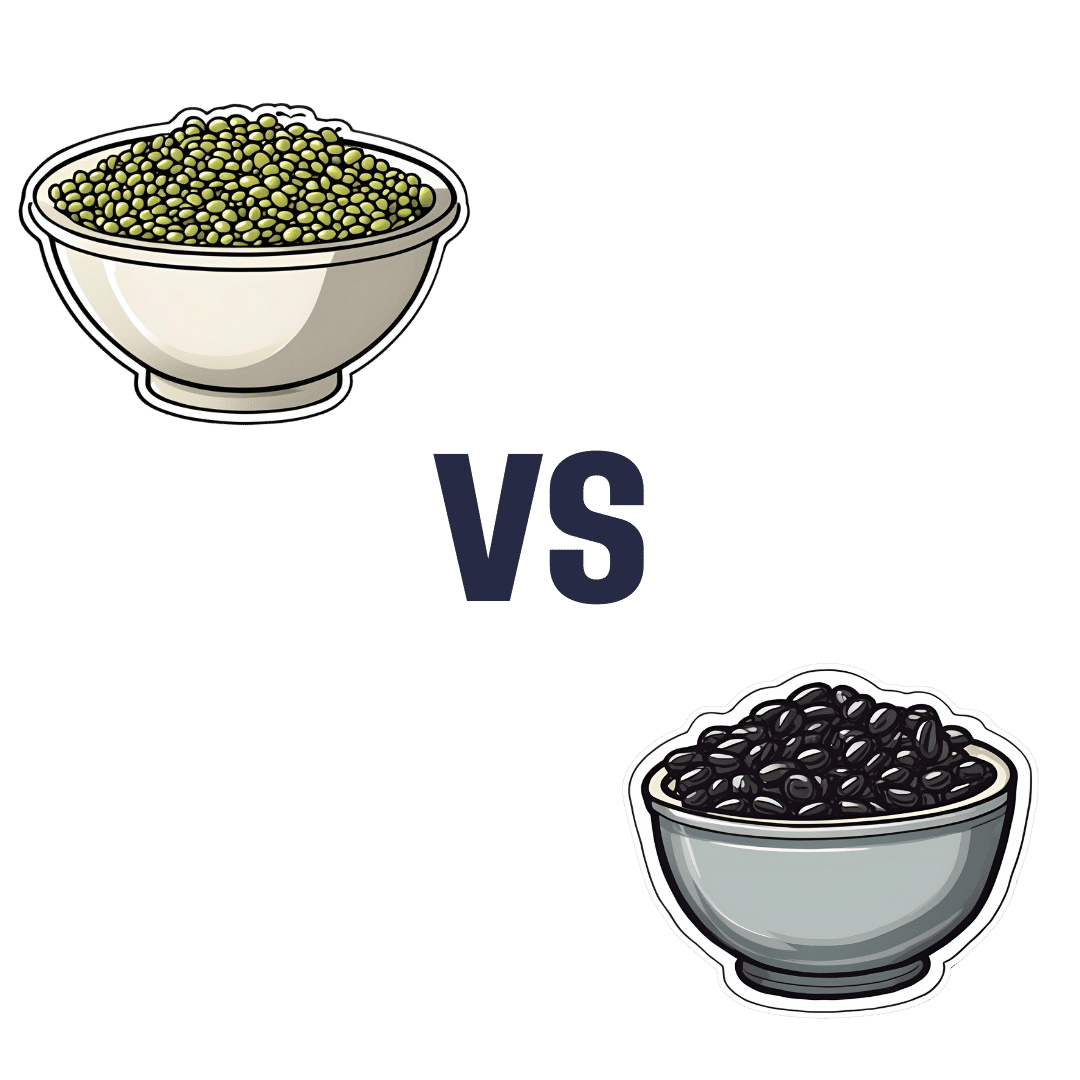

Mung Beans vs Black Beans – Which is Healthier?

10almonds is reader-supported. We may, at no cost to you, receive a portion of sales if you purchase a product through a link in this article.

Our Verdict

When comparing mung beans to black beans, we picked the black beans.

Why?

Both are great! But…

In terms of macros, black beans have more protein, carbs, and fiber, as well as the lower glycemic index (although both are already low). So, a clear win for black beans here.

In the category of vitamins, mung beans have more of vitamins A, B5, B9, and C, while black beans have more of vitamins B1, B6, E, K, and choline. Thus, a slight win for black beans this time.

When it comes to minerals, mung beans have more selenium and zinc, while black beans have more calcium, copper, iron, magnesium, manganese, phosphorus, and potassium. An easy win for black beans.

Of course, enjoy either or both—but if you’re going to pick one, we say black beans win the day.

Want to learn more?

You might like to read:

Plant vs Animal Protein: Head-to-Head

Take care!

Don’t Forget…

Did you arrive here from our newsletter? Don’t forget to return to the email to continue learning!

Learn to Age Gracefully

Join the 98k+ American women taking control of their health & aging with our 100% free (and fun!) daily emails:

-

What Do The Different Kinds Of Fiber Do? 30 Foods That Rank Highest

10almonds is reader-supported. We may, at no cost to you, receive a portion of sales if you purchase a product through a link in this article.

We’ve talked before about how important fiber is:

Why You’re Probably Not Getting Enough Fiber (And How To Fix It)

And even how it’s arguably the most important dietary factor when it comes to avoiding heart disease:

What Matters Most For Your Heart? Eat More (Of This) For Lower Blood Pressure ← Spoiler: it’s fiber

And yes, that’s even when considered alongside other (also laudable) dietary interventions such as lowering intake of sodium, various kinds of saturated fat, and red meat.

So, what should we know about fiber, aside from “aim to get nearer 40g/day instead of the US average 16g/day”?

Soluble vs Insoluble

The first main way that dietary fibers can be categorized is soluble vs insoluble. Part of the difference is obvious, but bear with us, because there’s more to know about each:

- Soluble fiber dissolves (what a surprise) in water and, which part is important, forms a gel. This slows down things going through your intestines, which is important for proper digestion and absorption of nutrients (as well as avoiding diarrhea). Yes, you heard right: getting enough of the right kind of fiber helps you avoid diarrhea.

- Insoluble fiber does not dissolve (how shocking) in water and thus mostly passes through undigested by us (some will actually be digested by gut microbes who subsist on this, and in return for us feeding them daily, they make useful chemicals for us). This kind of fiber is also critical for healthy bowel movements, because without it, constipation can ensue.

Both kinds of fiber improve just about every metric related to blood, including improving triglycerides and improving insulin sensitivity and blood glucose levels. Thus, they help guard against various kinds of cardiovascular disease, diabetes, and metabolic disease in general. Do note that because whatever’s good for your heart/blood is good for your brain (which requires a healthy heart and bloodstream to nourish it and take away waste), likely this also has a knock-on effect against cognitive decline, but we don’t have hard science for that claim so we’re going to leave that last item as a “likely”.

However, one thing’s for sure: if you want a healthy gut, heart, and brain, you need a good balance of soluble and insoluble fibers.

10 of the best for soluble fiber

Food Soluble Fiber Type(s) Soluble Fiber (g per serving) Insoluble Fiber Type(s) Insoluble Fiber (g per serving) Total Fiber (g per serving) Kidney beans (1 cup cooked) Pectin, Resistant Starch 1.5–2 Hemicellulose, Cellulose 6 8 Lentils (1 cup cooked) Pectin, Resistant Starch 1.5–2 Cellulose 6 7.5 Barley (1 cup cooked) Beta-glucan 3–4 Hemicellulose 2 6 Brussels sprouts (1 cup cooked) Pectin 1–1.5 Cellulose, Hemicellulose 2 3.5 Oats (1 cup cooked) Beta-glucan 2–3 Cellulose 1 3 Apples (1 medium) Pectin 1–2 Cellulose, Hemicellulose 2 3 Carrots (1 cup raw) Pectin 1–1.5 Cellulose, Hemicellulose 2 3 Citrus fruits (orange, 1 medium) Pectin 1–1.5 Cellulose 1 2.5 Flaxseeds (2 tbsp) Mucilage, Lignin 1–1.5 Cellulose 1 2.5 Psyllium husk (1 tbsp) Mucilage 3–4 Trace amounts 0 3–4 10 of the best for insoluble fiber

Food Soluble Fiber Type(s) Soluble Fiber (g per serving) Insoluble Fiber Type(s) Insoluble Fiber (g per serving) Total Fiber (g per serving) Wheat bran (1 cup) Trace amounts 0 Cellulose, Lignin 6–8 6–8 Black beans (1 cup cooked) Pectin, Resistant Starch 1.5 Cellulose 6 7.5 Brown rice (1 cup cooked) Trace amounts 0.5 Hemicellulose, Lignin 2–3 2.5–3.5 Popcorn (3 cups popped) Trace amounts 0.5 Hemicellulose 3 3.5 Broccoli (1 cup cooked) Pectin 1 Cellulose, Hemicellulose 4 5 Green beans (1 cup cooked) Trace amounts 0.5 Cellulose, Hemicellulose 3 3.5 Sweet potatoes (1 cup cooked) Pectin 1–1.5 Cellulose 3 4.5 Whole wheat bread (1 slice) Trace amounts 0.5 Cellulose, Hemicellulose 1 1.5 Pears (1 medium) Pectin 1 Cellulose, Hemicellulose 4 5 Almonds (1 oz) Trace amounts 0.5 Cellulose, Hemicellulose 2 2.5 10 of the best for a balance of both

Food Soluble Fiber Type(s) Soluble Fiber (g per serving) Insoluble Fiber Type(s) Insoluble Fiber (g per serving) Total Fiber (g per serving) Raspberries (1 cup) Pectin 1 Cellulose 5 6 Edamame (1 cup cooked) Pectin 1 Cellulose 5 6 Chia seeds (2 tbsp) Mucilage, Pectin 2–3 Lignin, Cellulose 3 5.5 Artichokes (1 medium) Inulin 1 Cellulose, Hemicellulose 5 6 Avocado (1 medium) Pectin ~2 Cellulose 4 6 Black beans (1 cup cooked) Pectin, Resistant Starch 1.5 Cellulose 6 7.5 Quinoa (1 cup cooked) Pectin, Saponins 1 Cellulose, Hemicellulose 3 4 Spinach (1 cup cooked) Pectin 0.5 Cellulose, Lignin 3 3.5 Prunes (1/2 cup) Pectin, Sorbitol 2 Cellulose 4 6 Figs (3 medium) Pectin 1 Cellulose 2 3 You’ll notice that the above “balance” is not equal; that’s ok; we need greater quantities of insoluble than soluble anyway, so it is as well that nature provides such.

This is the same kind of balance when we talk about “balanced hormones” (does not mean all hormones are in equal amounts; means they are in the right proportions) or “balanced microbiome” (does not mean that pathogens and friendly bacteria are in equal numbers), etc.

Some notes on the above:

About those fiber types, some of the most important soluble ones to aim for are:

- Beta-glucan: found in oats and barley, it supports heart health.

- Pectin: found in fruits like apples, citrus, and pears, it helps with cholesterol control.

- Inulin: a type of prebiotic fiber found in artichokes.

- Lignin: found in seeds and wheat bran, it has antioxidant properties.

- Resistant starch: found in beans and lentils, it acts as a prebiotic for gut health.

See also: When Is A Fiber Not A Fiber? The Food Additive You Do Want

One fiber to rule them all

Well, not entirely (we still need the others) but there is a best all-rounder:

The Best Kind Of Fiber For Overall Health?

Enjoy!

Don’t Forget…

Did you arrive here from our newsletter? Don’t forget to return to the email to continue learning!

Learn to Age Gracefully

Join the 98k+ American women taking control of their health & aging with our 100% free (and fun!) daily emails: