Is cold water bad for you? The facts behind 5 water myths

10almonds is reader-supported. We may, at no cost to you, receive a portion of sales if you purchase a product through a link in this article.

We know the importance of staying hydrated, especially in hot weather. But even for something as simple as a drink of water, conflicting advice and urban myths abound.

Is cold water really bad for your health? What about hot water from the tap? And what is “raw water”? Let’s dive in and find out.

Myth 1: Cold water is bad for you

Some recent TikToks have suggested cold water causes health problems by somehow “contracting blood vessels” and “restricting digestion”. There is little evidence for this.

While a 2001 study found 51 out of 669 women tested (7.6%) got a headache after drinking cold water, most of them already suffered from migraines and the work hasn’t been repeated since.

Cold drinks were shown to cause discomfort in people with achalasia (a rare swallowing disorder) in 2012 but the study only had 12 participants.

For most people, the temperature you drink your water is down to personal preference and circumstances. Cold water after exercise in summer or hot water to relax in winter won’t make any difference to your overall health.

Myth 2: You shouldn’t drink hot tap water

This belief has a grain of scientific truth behind it. Hot water is generally a better solvent than cold water, so may dissolve metals and minerals from pipes better. Hot water is also often stored in tanks and may be heated and cooled many times. Bacteria and other disease-causing microorganisms tend to grow better in warm water and can build up over time.

It’s better to fill your cup from the cold tap and get hot water for drinks from the kettle.

Myth 3: Bottled water is better

While bottled water might be safer in certain parts of the world due to pollution of source water, there is no real advantage to drinking bottled water in Australia and similar countries.

According to University of Queensland researchers, bottled water is not safer than tap water. It may even be tap water. Most people can’t tell the difference either. Bottled water usually costs (substantially) more than turning on the tap and is worse for the environment.

What about lead in tap water? This problem hit the headlines after a public health emergency in Flint, Michigan, in the United States. But Flint used lead pipes with a corrosion inhibitor (in this case orthophosphate) to keep lead from dissolving. Then the city switched water sources to one without a corrosion inhibitor. Lead levels rose and a public emergency was declared.

Fortunately, lead pipes haven’t been used in Australia since the 1930s. While lead might be present in some old plumbing products, it is unlikely to cause problems.

Myth 4: Raw water is naturally healthier

Some people bypass bottled and tap water, going straight to the source.

The “raw water” trend emerged a few years ago, encouraging people to drink from rivers, streams and lakes. There is even a website to help you find a local source.

Supporters say our ancestors drank spring water, so we should, too. However, our ancestors also often died from dysentery and cholera and their life expectancy was low.

While it is true even highly treated drinking water can contain low levels of things like microplastics, unless you live somewhere very remote, the risks of drinking untreated water are far higher as it is more likely to contain pollutants from the surrounding area.

Myth 5: It’s OK to drink directly from hoses

Tempting as it may be, it’s probably best not to drink from the hose when watering the plants. Water might have sat in there, in the warm sun for weeks or more potentially leading to bacterial buildup.

Similarly, while drinking water fountains are generally perfectly safe to use, they can contain a variety of bacteria. It’s useful (though not essential) to run them for a few seconds before you start to drink so as to get fresh water through the system rather than what might have been sat there for a while.

We are fortunate to be able to take safe drinking water for granted. Billions of people around the world are not so lucky.

So whether you like it hot or cold, or somewhere in between, feel free to enjoy a glass of water this summer.

Just don’t drink it from the hose.

Oliver A.H. Jones, Professor of chemistry, RMIT University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Don’t Forget…

Did you arrive here from our newsletter? Don’t forget to return to the email to continue learning!

Recommended

Learn to Age Gracefully

Join the 98k+ American women taking control of their health & aging with our 100% free (and fun!) daily emails:

-

Why do I keep getting urinary tract infections? And why are chronic UTIs so hard to treat?

10almonds is reader-supported. We may, at no cost to you, receive a portion of sales if you purchase a product through a link in this article.

Dealing with chronic urinary tract infections (UTIs) means facing more than the occasional discomfort. It’s like being on a never ending battlefield against an unseen adversary, making simple daily activities a trial.

UTIs happen when bacteria sneak into the urinary system, causing pain and frequent trips to the bathroom.

Chronic UTIs take this to the next level, coming back repeatedly or never fully going away despite treatment. Chronic UTIs are typically diagnosed when a person experiences two or more infections within six months or three or more within a year.

They can happen to anyone, but some are more prone due to their body’s makeup or habits. Women are more likely to get UTIs than men, due to their shorter urethra and hormonal changes during menopause that can decrease the protective lining of the urinary tract. Sexually active people are also at greater risk, as bacteria can be transferred around the area.

Up to 60% of women will have at least one UTI in their lifetime. While effective treatments exist, about 25% of women face recurrent infections within six months. Around 20–30% of UTIs don’t respond to standard antibiotic. The challenge of chronic UTIs lies in bacteria’s ability to shield themselves against treatments.

Why are chronic UTIs so hard to treat?

Once thought of as straightforward infections cured by antibiotics, we now know chronic UTIs are complex. The cunning nature of the bacteria responsible for the condition allows them to hide in bladder walls, out of antibiotics’ reach.

The bacteria form biofilms, a kind of protective barrier that makes them nearly impervious to standard antibiotic treatments.

This ability to evade treatment has led to a troubling increase in antibiotic resistance, a global health concern that renders some of the conventional treatments ineffective.

Some antibiotics no longer work against UTIs.

Michael Ebardt/ShutterstockAntibiotics need to be advanced to keep up with evolving bacteria, in a similar way to the flu vaccine, which is updated annually to combat the latest strains of the flu virus. If we used the same flu vaccine year after year, its effectiveness would wane, just as overused antibiotics lose their power against bacteria that have adapted.

But fighting bacteria that resist antibiotics is much tougher than updating the flu vaccine. Bacteria change in ways that are harder to predict, making it more challenging to create new, effective antibiotics. It’s like a never-ending game where the bacteria are always one step ahead.

Treating chronic UTIs still relies heavily on antibiotics, but doctors are getting crafty, changing up medications or prescribing low doses over a longer time to outwit the bacteria.

Doctors are also placing a greater emphasis on thorough diagnostics to accurately identify chronic UTIs from the outset. By asking detailed questions about the duration and frequency of symptoms, health-care providers can better distinguish between isolated UTI episodes and chronic conditions.

The approach to initial treatment can significantly influence the likelihood of a UTI becoming chronic. Early, targeted therapy, based on the specific bacteria causing the infection and its antibiotic sensitivity, may reduce the risk of recurrence.

For post-menopausal women, estrogen therapy has shown promise in reducing the risk of recurrent UTIs. After menopause, the decrease in estrogen levels can lead to changes in the urinary tract that makes it more susceptible to infections. This treatment restores the balance of the vaginal and urinary tract environments, making it less likely for UTIs to occur.

Lifestyle changes, such as drinking more water and practising good hygiene like washing hands with soap after going to the toilet and the recommended front-to-back wiping for women, also play a big role.

Some swear by cranberry juice or supplements, though researchers are still figuring out how effective these remedies truly are.

What treatments might we see in the future?

Scientists are currently working on new treatments for chronic UTIs. One promising avenue is the development of vaccines aimed at preventing UTIs altogether, much like flu shots prepare our immune system to fend off the flu.

Emerging treatments could help clear chronic UTIs.

guys_who_shoot/ShutterstockAnother new method being looked at is called phage therapy. It uses special viruses called bacteriophages that go after and kill only the bad bacteria causing UTIs, while leaving the good bacteria in our body alone. This way, it doesn’t make the bacteria resistant to treatment, which is a big plus.

Researchers are also exploring the potential of probiotics. Probiotics introduce beneficial bacteria into the urinary tract to out-compete harmful pathogens. These good bacteria work by occupying space and resources in the urinary tract, making it harder for harmful pathogens to establish themselves.

Probiotics can also produce substances that inhibit the growth of harmful bacteria and enhance the body’s immune response.

Chronic UTIs represent a stubborn challenge, but with a mix of current treatments and promising research, we’re getting closer to a day when chronic UTIs are a thing of the past.

Iris Lim, Assistant Professor, Bond University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Share This Post

-

Burn – by Dr. Herman Pontzer

10almonds is reader-supported. We may, at no cost to you, receive a portion of sales if you purchase a product through a link in this article.

We all have reasons to want to focus on our metabolism. Speed it up to burn more fat; slow it down to live longer. Tweak it for more energy in the day. But what actually is it, and how does it work?

Dr. Herman Pontzer presents a very useful overview of not just what our metabolism is and how it works, but also why.

The style of the book is casual, but doesn’t skimp on the science. Whether we are getting campfire stories of Hadza hunter-gatherers, or an explanation of the use of hydrogen isotopes in metabolic research, Dr. Pontzer keeps things easy-reading.

One of the main premises of the book is that our caloric expenditure is not easy to change—if we exercise more, our bodies will cut back somewhere else. After all, the body uses energy for a lot more than just moving. With this in mind, Dr. Pontzer makes the science-based case for focusing more on diet than exercise if weight management is our goal.

In short, if you’d like your metabolism to be a lot less mysterious, this book can help render a lot of science a lot more comprehensible!

Share This Post

-

What is ‘doll therapy’ for people with dementia? And is it backed by science?

10almonds is reader-supported. We may, at no cost to you, receive a portion of sales if you purchase a product through a link in this article.

The way people living with dementia experience the world can change as the disease progresses. Their sense of reality or place in time can become distorted, which can cause agitation and distress.

One of the best ways to support people experiencing changes in perception and behaviour is to manage their environment. This can have profound benefits including reducing the need for sedatives.

One such strategy is the use of dolls as comfort aids.

Jack Cronkhite/Shutterstock What is ‘doll therapy’?

More appropriately referred to as “child representation”, lifelike dolls (also known as empathy dolls) can provide comfort for some people with dementia.

Memories from the distant past are often more salient than more recent events in dementia. This means that past experiences of parenthood and caring for young children may feel more “real” to a person with dementia than where they are now.

Hallucinations or delusions may also occur, where a person hears a baby crying or fears they have lost their baby.

Providing a doll can be a tangible way of reducing distress without invalidating the experience of the person with dementia.

Some people believe the doll is real

A recent case involving an aged care nurse mistreating a dementia patient’s therapy doll highlights the importance of appropriate training and support for care workers in this area.

For those who do become attached to a therapeutic doll, they will treat the doll as a real baby needing care and may therefore have a profound emotional response if the doll is mishandled.

It’s important to be guided by the person with dementia and only act as if it’s a real baby if the person themselves believes that is the case.

What does the evidence say about their use?

Evidence shows the use of empathy dolls may help reduce agitation and anxiety and improve overall quality of life in people living with dementia.

Child representation therapy falls under the banner of non-pharmacological approaches to dementia care. More specifically, the attachment to the doll may act as a form of reminiscence therapy, which involves using prompts to reconnect with past experiences.

Interacting with the dolls may also act as a form of sensory stimulation, where the person with dementia may gain comfort from touching and holding the doll. Sensory stimulation may support emotional well-being and aid commnication.

However, not all people living with dementia will respond to an empathy doll.

It depends on a person’s background. Shutterstock The introduction of a therapeutic doll needs to be done in conjunction with careful observation and consideration of the person’s background.

Empathy dolls may be inappropriate or less effective for those who have not previously cared for children or who may have experienced past birth trauma or the loss of a child.

Be guided by the person with dementia and how they respond to the doll.

Are there downsides?

The approach has attracted some controversy. It has been suggested that child representation therapy “infantilises” people living with dementia and may increase negative stigma.

Further, the attachment may become so strong that the person with dementia will become upset if someone else picks the doll up. This may create some difficulties in the presence of grandchildren or when cleaning the doll.

The introduction of child representation therapy may also require additional staff training and time. Non-pharmacological interventions such as child representation, however, have been shown to be cost-effective.

Could robots be the future?

The use of more interactive empathy dolls and pet-like robots is also gaining popularity.

While robots have been shown to be feasible and acceptable in dementia care, there remains some contention about their benefits.

While some studies have shown positive outcomes, including reduced agitation, others show no improvement in cognition, behaviour or quality of life among people with dementia.

Advances in artificial intelligence are also being used to help support people living with dementia and inform the community.

Viv and Friends, for example, are AI companions who appear on a screen and can interact with the person with dementia in real time. The AI character Viv has dementia and was co-created with women living with dementia using verbatim scripts of their words, insights and experiences. While Viv can share her experience of living with dementia, she can also be programmed to talk about common interests, such as gardening.

These companions are currently being trialled in some residential aged care facilities and to help educate people on the lived experience of dementia.

How should you respond to your loved one’s empathy doll?

While child representation can be a useful adjunct in dementia care, it requires sensitivity and appropriate consideration of the person’s needs.

People living with dementia may not perceive the social world the same way as a person without dementia. But a person living with dementia is not a child and should never be treated as one.

Ensure all family, friends and care workers are informed about the attachment to the empathy doll to help avoid unintentionally causing distress from inappropriate handling of the doll.

If using an interactive doll, ensure spare batteries are on hand.

Finally, it is important to reassess the attachment over time as the person’s response to the empathy doll may change.

Nikki-Anne Wilson, Postdoctoral Research Fellow, Neuroscience Research Australia (NeuRA), UNSW Sydney

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Share This Post

Related Posts

-

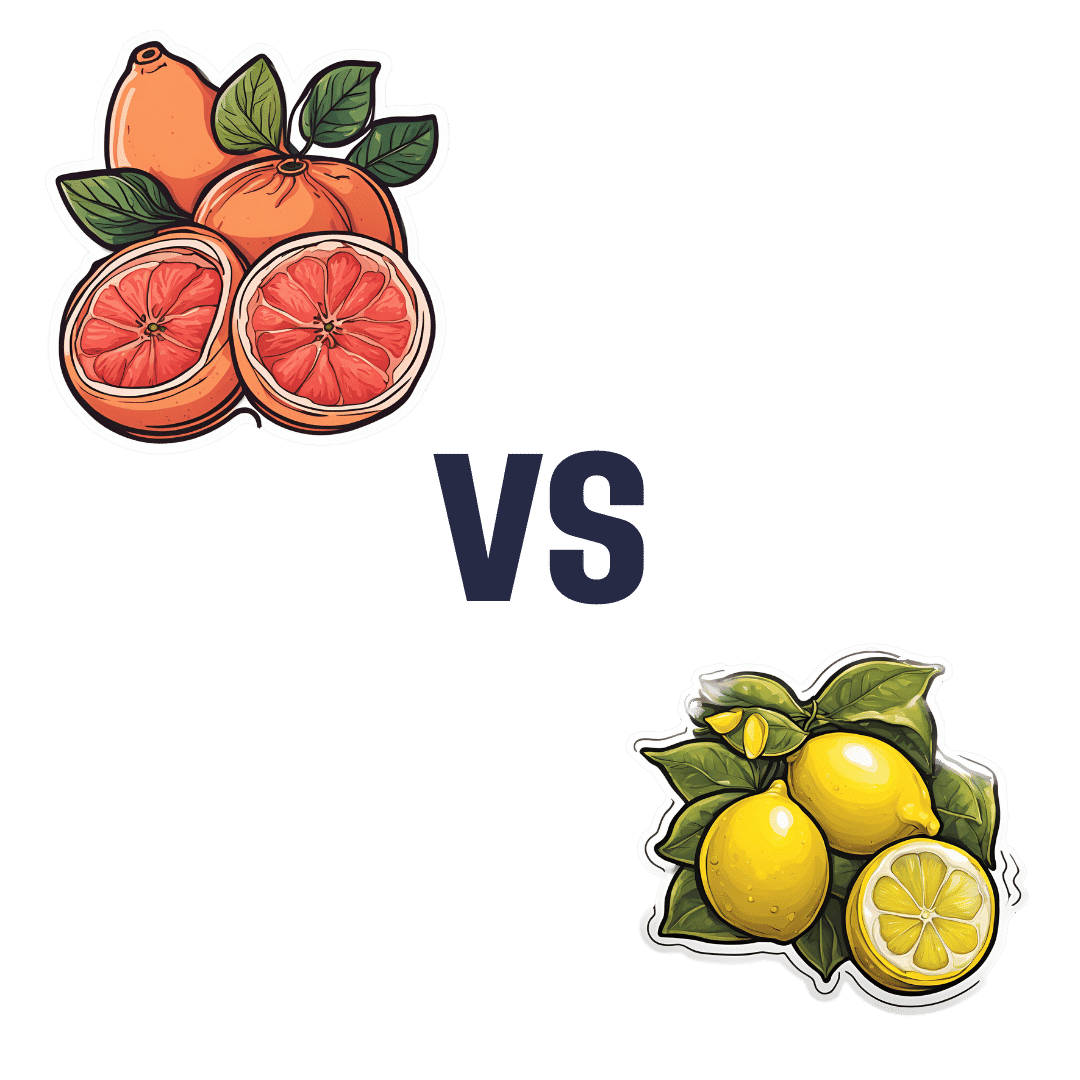

Grapefruit vs Lemon – Which is Healthier?

10almonds is reader-supported. We may, at no cost to you, receive a portion of sales if you purchase a product through a link in this article.

Our Verdict

When comparing grapefruit to lemon, we picked the lemon.

Why?

Grapefruit has its merits, but in the battle of the citrus fruits, lemons come out on top nutritionally:

In terms of macros, grapefruit has more carbs while lemons have more fiber. So, while both have a low glycemic index, lemon is still the winner by the numbers.

Looking at the vitamins, here we say grapefruit’s strengths: grapefruit has more of vitamins A, B2, B3, and choline, while lemon has more of vitamins B6 and C. So, a 4:2 win for grapefruit here.

In the category of minerals, lemons retake the lead: grapefruit has more zinc, while lemon has more calcium, copper, iron, manganese, and selenium.

One final consideration that’s not shown in the nutritional values, is that grapefruit contains high levels of furanocoumarin, which can inhibit cytochrome P-450 3A4 isoenzyme and P-glycoptrotein transporters in the intestine and liver—slowing down their drug metabolism capabilities, thus effectively increasing the bioavailability of many drugs manifold.

This may sound superficially like a good thing (improving bioavailability of things we want), but in practice it means that in the case of many drugs, if you take them with (or near in time to) grapefruit or grapefruit juice, then congratulations, you just took an overdose. This happens with a lot of meds for blood pressure, cholesterol (including statins), calcium channel-blockers, anti-depressants, benzo-family drugs, beta-blockers, and more. Oh, and Viagra, too. Which latter might sound funny, but remember, Viagra’s mechanism of action is blood pressure modulation, and that is not something you want to mess around with unduly. So, do check with your pharmacist to know if you’re on any meds that would be affected by grapefruit or grapefruit juice!

PS: the same substance is quite available in pummelos and sour oranges (but not meaningfully in sweet oranges); you can see a chart here showing the relative furanocoumarin contents of many citrus fruits, or lack thereof as the case may be, as it is for lemons and most limes)

Adding up the sections gives us a clear win for lemons, but by all means enjoy either or both; just watch out for that furanocoumarin content of grapefruit if you’re on any meds affected by such (again, do check with your pharmacist, as our list was far from exhaustive—and yes, this question is one that a pharmacist will answer more easily and accurately than a doctor will).

Want to learn more?

You might like to read:

Top 8 Fruits That Prevent & Kill Cancer ← citrus fruits in general make the list; they inhibit tumor growth and kill cancer cells; regular consumption is also associated with a lower cancer risk 🙂

Enjoy!

Don’t Forget…

Did you arrive here from our newsletter? Don’t forget to return to the email to continue learning!

Learn to Age Gracefully

Join the 98k+ American women taking control of their health & aging with our 100% free (and fun!) daily emails:

-

In Vermont, Where Almost Everyone Has Insurance, Many Can’t Find or Afford Care

10almonds is reader-supported. We may, at no cost to you, receive a portion of sales if you purchase a product through a link in this article.

RICHMOND, Vt. — On a warm autumn morning, Roger Brown walked through a grove of towering trees whose sap fuels his maple syrup business. He was checking for damage after recent flooding. But these days, his workers’ health worries him more than his trees’.

The cost of Slopeside Syrup’s employee health insurance premiums spiked 24% this year. Next year it will rise 14%.

The jumps mean less money to pay workers, and expensive insurance coverage that doesn’t ensure employees can get care, Brown said. “Vermont is seen as the most progressive state, so how is health care here so screwed up?”

Vermont consistently ranks among the healthiest states, and its unemployment and uninsured rates are among the lowest. Yet Vermonters pay the highest prices nationwide for individual health coverage, and state reports show its providers and insurers are in financial trouble. Nine of the state’s 14 hospitals are losing money, and the state’s largest insurer is struggling to remain solvent. Long waits for care have become increasingly common, according to state reports and interviews with residents and industry officials.

Rising health costs are a problem across the country, but Vermont’s situation surprises health experts because virtually all its residents have insurance and the state regulates care and coverage prices.

For more than 15 years, federal and state policymakers have focused on increasing the number of people insured, which they expected would shore up hospital finances and make care more available and affordable.

“Vermont’s struggles are a wake-up call that insurance is only one piece of the puzzle to ensuring access to care,” said Keith Mueller, a rural health expert at the University of Iowa.

Regulators and consultants say the state’s small, aging population of about 650,000 makes spreading insurance risk difficult. That demographic challenge is compounded by geography, as many Vermonters live in rural areas, where it’s difficult to attract more health workers to address shortages.

At least part of the cost spike can be attributed to patients crossing state lines for quicker care in New York and Massachusetts. Those visits can be more expensive for both insurers and patients because of long ambulance rides and charges from out-of-network providers.

Patients who stay, like Lynne Drevik, face long waits. Drevik said her doctor told her in April that she needed knee replacement surgeries — but the earliest appointment would be in January for one knee and the following April for the other.

Drevik, 59, said it hurts to climb the stairs in the 19th-century farmhouse in Montgomery Center she and her husband operate as an inn and a spa. “My life is on hold here, and it’s hard to make any plans,” she said. “It’s terrible.”

Health experts say some of the state’s health system troubles are self-inflicted.

Unlike most states, Vermont regulates hospital and insurance prices through an independent agency, the Green Mountain Care Board. Until recently, the board typically approved whatever price changes companies wanted, said Julie Wasserman, a health consultant in Vermont.

The board allowed one health system — the University of Vermont Health Network — to control about two-thirds of the state’s hospital market and allowed its main facility, the University of Vermont Medical Center in Burlington, to raise its prices until it ranked among the nation’s most expensive, she said, citing data the board presented in September.

Hospital officials contend their prices are no higher than industry averages.

But for 2025, the board required the University of Vermont Medical Center to cut the prices it bills private insurers by 1%.

The nonprofit system says it is navigating its own challenges. Top officials say a severe lack of housing makes it hard to recruit workers, while too few mental health providers, nursing homes, and long-term care services often create delays in discharging patients, adding to costs.

Two-thirds of the system’s patients are covered by Medicare or Medicaid, said CEO Sunny Eappen. Both government programs pay providers lower rates than private insurance, which Eappen said makes it difficult to afford rising prices for drugs, medical devices, and labor.

Officials at the University of Vermont Medical Center point to several ways they are trying to adapt. They cited, for example, $9 million the hospital system has contributed to the construction of two large apartment buildings to house new workers, at a subsidized price for lower-income employees.

The hospital also has worked with community partners to open a mental health urgent care center, providing an alternative to the emergency room.

In the ER, curtains separate areas in the hallway where patients can lie on beds or gurneys for hours waiting for a room. The hospital also uses what was a storage closet as an overflow room to provide care.

“It’s good to get patients into a hallway, as it’s better than a chair,” said Mariah McNamara, an ER doctor and associate chief medical officer with the hospital.

For the about 250 days a year when the hospital is full, doctors face pressure to discharge patients without the ideal home or community care setup, she said. “We have to go in the direction of letting you go home without patient services and giving that a try, because otherwise the hospital is going to be full of people, and that includes people that don’t need to be here,” McNamara said.

Searching for solutions, the Green Mountain Care Board hired a consultant who recommended a number of changes, including converting four rural hospitals into outpatient facilities, in a worst-case scenario, and consolidating specialty services at several others.

The consultant, Bruce Hamory, said in a call with reporters that his report provides a road map for Vermont, where “the health care system is no match for demographic, workforce, and housing challenges.”

But he cautioned that any fix would require sacrifice from everyone, including patients, employers, and health providers. “There is no simple single policy solution,” he said.

One place Hamory recommended converting to an outpatient center only was North Country Hospital in Newport, a village in Vermont’s least populated region, known as the Northeast Kingdom.

The 25-bed hospital has lost money for years, partly because of an electronic health record system that has made it difficult to bill patients. But the hospital also has struggled to attract providers and make enough money to pay them.

Officials said they would fight any plans to close the hospital, which recently dropped several specialty services, including pulmonology, neurology, urology, and orthopedics. It doesn’t have the cash to upgrade patient rooms to include bathroom doors wide enough for wheelchairs.

On a recent morning, CEO Tom Frank walked the halls of his hospital. The facility was quiet, with just 14 admitted patients and only a couple of people in the ER. “This place used to be bustling,” he said of the former pulmonology clinic.

Frank said the hospital breaks even treating Medicare patients, loses money treating Medicaid patients, and makes money from a dwindling number of privately insured patients.

The state’s strict regulations have earned it an antihousing, antibusiness reputation, he said. “The cost of health care is a symptom of a larger problem.”

About 30 miles south of Newport, Andy Kehler often worries about the cost of providing health insurance to the 85 workers at Jasper Hill Farm, the cheesemaking business he co-owns.

“It’s an issue every year for us, and it looks like there is no end in sight,” he said.

Jasper Hill pays half the cost of its workers’ health insurance premiums because that’s all it can afford, Kehler said. Employees pay $1,700 a month for a family, with a $5,000 deductible.

“The coverage we provide is inadequate for what you pay,” he said.

KFF Health News is a national newsroom that produces in-depth journalism about health issues and is one of the core operating programs at KFF—an independent source of health policy research, polling, and journalism. Learn more about KFF.

Subscribe to KFF Health News’ free Morning Briefing.

This article first appeared on KFF Health News and is republished here under a Creative Commons license.

Don’t Forget…

Did you arrive here from our newsletter? Don’t forget to return to the email to continue learning!

Learn to Age Gracefully

Join the 98k+ American women taking control of their health & aging with our 100% free (and fun!) daily emails:

-

Digital Minimalism – by Dr. Cal Newport

10almonds is reader-supported. We may, at no cost to you, receive a portion of sales if you purchase a product through a link in this article.

There are a lot of books that advise “Unplug once in a while, and go outside”. But it doesn’t really take a book to convey that, does it? And it just leaves all the digital catching-up once we get back. Surely there must be a better way?

Rather than relying on a “digital detox”, Dr. Newport offers principles to apply to our digital lives, that allow us to reap the benefits of modern information technology without being obeisant to it.

The book’s greatest strength lies in that; having clear guidelines that can be applied to cut out the extra weight of digital media that has simply snuck in because of The Almighty Algorithm—and even tips on how to engage more mindfully with that if we still want to, for example using social media only in a web browser rather than on our phones, so that we can ringfence the time for it rather than having it spill into every spare moment.

In the category of criticism, the book sometimes lacks a little awareness when it comes to assumptions about the reader and the reader’s social circles; that (for example) nobody has any disabilities and everyone lives in the same town. But for most people most of the time, the advices will stand, and the exceptions can be managed by the reader neatly enough.

Stylistically, the book is not very minimalist, but this is not inconsistent with the advice of the book, if you’re curling up in the armchair with a physical copy, or a single-purpose ereader device.

Bottom line: if you’d like to streamline your use of digital media, but don’t want to lose out on the value it brings you, this book provides an excellent template

Click here to check out Digital Minimalism, and choose focused life in a noisy world!

Don’t Forget…

Did you arrive here from our newsletter? Don’t forget to return to the email to continue learning!

Learn to Age Gracefully

Join the 98k+ American women taking control of their health & aging with our 100% free (and fun!) daily emails: