Grain Brain – by Dr. David Perlmutter

10almonds is reader-supported. We may, at no cost to you, receive a portion of sales if you purchase a product through a link in this article.

If you’re a regular 10almonds reader, you probably know that refined flour, and processed food in general, is not great for the health. So, what does this book offer more?

Dr. Perlmutter sets out the case against (as the subtitle suggests) wheat, carbs, and sugar. Yes, including wholegrain wheat, and including starchy vegetables such as potatoes and parsnips. Fruit does also come under scrutiny, a clear distinction is made between whole fruits and juices. In the latter case, the lack of fiber (along with the more readily absorbable liquid state) allows for those sugars to zip straight into our blood.

The book includes lots of stats and facts, and many study citations, along with infographics and clear explanations.

If the book has a weakness, it’s when it forgets to clarify something that was obvious to the author. For example, when he talks about our ancestors’ diets being 75% fat and 5% carbs, he neglects to mention that this is 75% by calorie count, not by mass or volume. This makes a huge difference! It’s the difference between a fat-guzzling engine, and someone who eats mostly fruit and oily nuts but also some very high-fat meat/organs.

The book’s strengths, on the other hand, are found in its explanation, backed by good science, of what wheat, along with excessive carbohydrates (especially sugar) can do to our body, including (and most focusedly, hence the title) our brain, leading the way to not just obvious metabolic disorders like diabetes, but also inflammatory diseases like Alzheimer’s.

Bottom line: you don’t have to completely revamp your diet if it’s working for you, but data is data, and this book has lots, making it well-worth a read.

Click here to check out Grain Brain, and learn about how to avoid inflaming yours!

Don’t Forget…

Did you arrive here from our newsletter? Don’t forget to return to the email to continue learning!

Recommended

Learn to Age Gracefully

Join the 98k+ American women taking control of their health & aging with our 100% free (and fun!) daily emails:

-

No Time to Panic – by Matt Gutman

10almonds is reader-supported. We may, at no cost to you, receive a portion of sales if you purchase a product through a link in this article.

Matt Gutman is not a doctor or a psychologist. He’s a journalist, accustomed to asking questions and then asking more probing questions, unrelenting until he gets the answers he’s looking for.

This book is the result of what happened when he needed to overcome his own anxiety and panic attacks, and went on an incisive investigative journey.

The style is as clear and accessible as you’d expect of a journalist, and presents a very human exploration, nonetheless organized in a way that will be useful to the reader.

It’s said that “experience is a great teacher, but she sends hefty bills”. In this case as in many, it’s good to learn from someone else’s experience!

By the end of the book, you’ll have a good grounding in most approaches to dealing with anxiety and panic attacks, and an idea of efficacy/applicability, and what to expect.

Bottom line: without claiming any magic bullet, this book presents six key strategies that Gutman found to work, along with his experiences of what didn’t. Valuable reading if you want to curb your own anxiety, or want to be able to help/support someone else with theirs.

Click here to check out No Time To Panic, and find the peace you deserve!

Share This Post

-

Cannabis Myths vs Reality

10almonds is reader-supported. We may, at no cost to you, receive a portion of sales if you purchase a product through a link in this article.

Cannabis Myths vs Reality

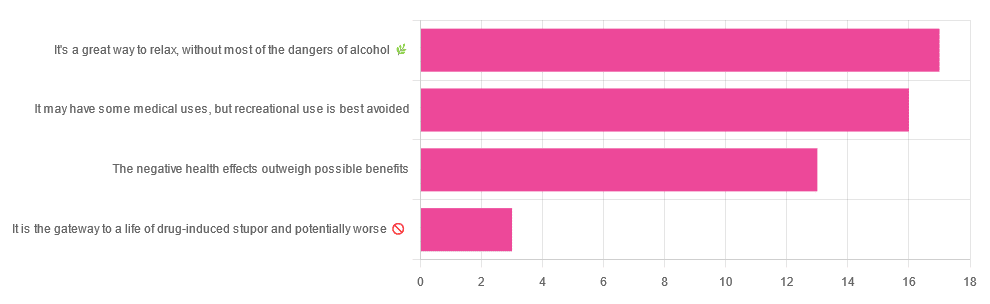

We asked you for your (health-related) opinion on cannabis use—specifically, the kind with psychoactive THC, not just CBD. We got the above-pictured, below-described, spread of responses:

- A little over a third of you voted for “It’s a great way to relax, without most of the dangers of alcohol”.

- A little under a third of you voted for “It may have some medical uses, but recreational use is best avoided”.

- About a quarter of you voted for “The negative health effects outweigh the possible benefits”

- Three of you voted for “It is the gateway to a life of drug-induced stupor and potentially worse”

So, what does the science say?

A quick legal note first: we’re a health science publication, and are writing from that perspective. We do not know your location, much less your local laws and regulations, and so cannot comment on such. Please check your own local laws and regulations in that regard.

Cannabis use can cause serious health problems: True or False?

True. Whether the risks outweigh the benefits is a personal and subjective matter (for example, a person using it to mitigate the pain of late stage cancer is probably unconcerned with many other potential risks), but what’s objectively true is that it can cause serious health problems.

One subscriber who voted for “The negative health effects outweigh the possible benefits” wrote:

❝At a bare minimum, you are ingesting SMOKE into your lungs!! Everyone SEEMS TO BE against smoking cigarettes, but cannabis smoking is OK?? Lung cancer comes in many forms.❞

Of course, that is assuming smoking cannabis, and not consuming it as an edible. But, what does the science say on smoking it, and lung cancer?

There’s a lot less research about this when it comes to cannabis, compared to tobacco. But, there is some:

❝Results from our pooled analyses provide little evidence for an increased risk of lung cancer among habitual or long-term cannabis smokers, although the possibility of potential adverse effect for heavy consumption cannot be excluded.❞

Read: Cannabis smoking and lung cancer risk: Pooled analysis in the International Lung Cancer Consortium

Another study agreed there appears to be no association with lung cancer, but that there are other lung diseases to consider, such as bronchitis and COPD:

❝Smoking cannabis is associated with symptoms of chronic bronchitis, and there may be a modest association with the development of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Current evidence does not suggest an association with lung cancer.❞

Read: Cannabis Use, Lung Cancer, and Related Issues

Cannabis edibles are much safer than smoking cannabis: True or False?

Broadly True, with an important caveat.

One subscriber who selected “It may have some medical uses, but recreational use is best avoided”, wrote:

❝I’ve been taking cannabis gummies for fibromyalgia. I don’t know if they’re helping but they’re not doing any harm. You cannot overdose you don’t become addicted.❞

Firstly, of course consuming edibles (rather than inhaling cannabis) eliminates the smoke-related risk factors we discussed above. However, other risks remain, including the much greater ease of accidentally overdosing.

❝Visits attributable to inhaled cannabis are more frequent than those attributable to edible cannabis, although the latter is associated with more acute psychiatric visits and more ED visits than expected.❞

Note: that “more frequent” for inhaled cannabis, is because more people inhale it than eat it. If we adjust the numbers to control for how much less often people eat it, suddenly we see that the numbers of hospital admissions are disproportionately high for edibles, compared to inhaled cannabis.

Or, as the study author put it:

❝There are more adverse drug events associated on a milligram per milligram basis of THC when it comes in form of edibles versus an inhaled cannabis. If 1,000 people smoked pot and 1,000 people at the same dose in an edible, then more people would have more adverse drug events from edible cannabis.❞

See the numbers: Acute Illness Associated With Cannabis Use, by Route of Exposure

Why does this happen?

- It’s often because edibles take longer to take effect, so someone thinks “this isn’t very strong” and has more.

- It’s also sometimes because someone errantly eats someone else’s edibles, not realising what they are.

- It’s sometimes a combination of the above problems: a person who is now high, may simply forget and/or make a bad decision when it comes to eating more.

On the other hand, that doesn’t mean inhaling it is necessarily safer. As well as the pulmonary issues we discussed previously, inhaling cannabis has a higher risk of cannabinoid hyperemesis syndrome (and the resultant cyclic vomiting that’s difficult to treat).

You can read about this fascinating condition that’s sometimes informally called “scromiting”, a portmanteau of screaming and vomiting:

Cannabinoid Hyperemesis Syndrome

You can’t get addicted to cannabis: True or False?

False. However, it is fair to say that the likelihood of developing a substance abuse disorder is lower than for alcohol, and much lower than for nicotine.

See: Prevalence of Marijuana Use Disorders in the United States Between 2001–2002 and 2012–2013

If you prefer just the stats without the science, here’s the CDC’s rendering of that:

Addiction (Marijuana or Cannabis Use Disorder)

However, there is an interesting complicating factor, which is age. One is 4–7 times more likely to develop a substance abuse disorder, if one starts use as an adolescent, rather than later in life:

Cannabis is the gateway to use of more dangerous drugs: True or False?

False, generally speaking. Of course, for any population there will be some outliers, but there appears to be no meaningful causal relation between cannabis use and other substance use:

Interestingly, the strongest association (where any existed at all) was between cannabis use and opioid use. However, rather than this being a matter of cannabis use being a gateway to opioid use, it seems more likely that this is a matter of people looking to both for the same purpose: pain relief.

As a result, growing accessibility of cannabis may actually reduce opioid problems:

- Cannabis as a Gateway Drug for Opioid Use Disorder

- Association between medical cannabis laws and opioid overdose mortality has reversed over time

Some final words…

Cannabis is a complex drug with complex mechanisms and complex health considerations, and research is mostly quite young, due to its historic illegality seriously cramping science by reducing sample sizes to negligible. Simply put, there’s a lot we still don’t know.

Also, we covered some important topics today, but there were others we didn’t have time to cover, such as the other potential psychological benefits—and risks. Likely we’ll revisit those another day.

Lastly, while we’ve covered a bunch of risks today, those of you who said it has fewer and lesser risks than alcohol are quite right—the only reason we couldn’t focus on that more, is because to talk about all the risks of alcohol would make this feature many times longer!

Meanwhile, whether you partake or not, stay safe and stay well.

Share This Post

-

The Vagus Nerve’s Power for Weight Loss

10almonds is reader-supported. We may, at no cost to you, receive a portion of sales if you purchase a product through a link in this article.

Dr. Arun Dhir is a university lecturer, a gastrointestinal surgeon, an author, and a yoga and meditation instructor, and he has this to say:

Gut feelings

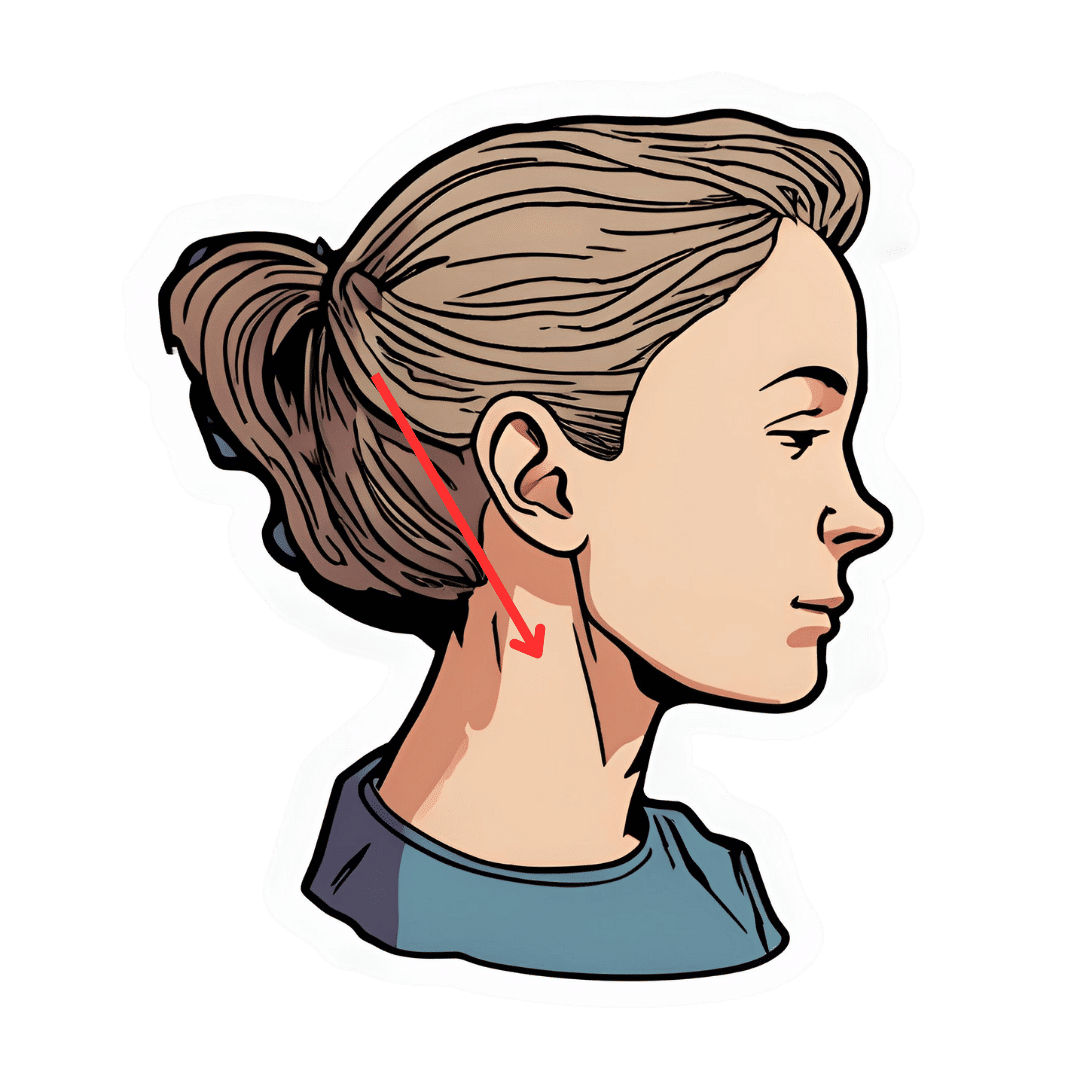

The vagus nerve is the 10th cranial nerve, also known as “vagus” (“the wanderer”), because it travels from the brain to many other body parts, including the ears, throat, heart, respiratory system, gut, pancreas, liver, and reproductive system. It’s no surprise then, that it plays a key role in brain-gut communication and metabolism regulation.

The vagus nerve is part of the parasympathetic nervous system, responsible for rest, digestion, and counteracting the stress response. Most signals through the vagus nerve travel from the gut to the brain, though there is communication in both directions.

You may be beginning to see how this works and its implications for weight management: the vagus nerve senses metabolites from the liver, pancreas, and small intestine, and regulates insulin production by stimulating beta cells in the pancreas, which is important for avoiding/managing insulin resistance and metabolic syndrome in general.

Dr. Dhir cites a study in which vagus nerve stimulation (originally used for treating epilepsy and depression) was shown to cause unintentional weight loss (6-11%) in patients, revealing a link to weight management. Of course, that is quite a specific sample, so more research is needed to say for sure, but because the principle is very sound and the mechanism of action is clear, it’s not being viewed as a controversial conclusion.

As for how get these benefits, here are seven ways:

- Cold water on the face: submerge your face in cold water in the morning while holding water in your mouth, or cover your face with a cold wet washcloth (while holding your breath please; no need to waterboard yourself!), which activates the “mammalian dive response” in which your body activates the parasympathetic nervous system in order to remain calm and thus survive for longer underwater

- Alternate hot and cold showers: switch between hot and cold water during showers for 10-second intervals; this creates eustress and activates the process of hormesis, improving your overall stress management and reducing any chronic stress response you may otherwise have going on

- Humming and gargling: the vibrations in the throat stimulate the nearby vagus nerve

- Deep breathing (pranayama): yoga breathing exercises, especially combined with somatic exercises such as the sun salutation, can stimulate the vagus nerve

- Intermittent fasting: helps recalibrate the metabolism and indirectly improves vagus nerve function

- Massage and acupressure: stimulates lymphatic channels and the vagus nerve

- Long walks in nature (“forest bathing”): helps trigger relaxation in general

For more on all of this, enjoy:

Click Here If The Embedded Video Doesn’t Load Automatically!

Want to learn more?

You might also like to read:

The Vagus Nerve (And How You Can Make Use Of It)

Take care!

Share This Post

Related Posts

-

Super Joints – by Pavel Tsatsouline

10almonds is reader-supported. We may, at no cost to you, receive a portion of sales if you purchase a product through a link in this article.

For those of us for whom mobility and pain-free movement are top priorities, this book has us covered. So what’s different here, compared to your average stretching book?

It’s about functional strength with the stretches. The author’s background as a special forces soldier means that his interest was not in doing arcane yoga positions so much as being able to change direction quickly without losing speed or balance, get thrown down and get back up without injury, twist suddenly without unpleasantly wrenching anything (of one’s own, at least), and generally be able to take knocks without taking damage.

While we are hopefully not having to deal with such violence in our everyday lives, the robustness of body that results from these exercises is one that certainly can go a long way to keep us injury-free.

The exercises themselves are well-described, clearly and succinctly, with equally clear illustrations.

Note: the paperback version is currently expensive, probably due to supply and demand, but if you select the Kindle version, it’s much cheaper with no loss of quality (because the illustrations are black-on-white line-drawings and very clear; perfect for Kindle e-ink)

The style of the book is very casual and conversational, yet somehow doesn’t let that distract it from being incredibly information dense; there is no fluff here, just valuable guidance.

Bottom line: if you would like to be more robust with non-nonsense exercises, then this book is a fine choice.

Click here to check out Super Joints, and make yours flexible and strong!

Don’t Forget…

Did you arrive here from our newsletter? Don’t forget to return to the email to continue learning!

Learn to Age Gracefully

Join the 98k+ American women taking control of their health & aging with our 100% free (and fun!) daily emails:

-

Young Forever – by Dr. Mark Hyman

10almonds is reader-supported. We may, at no cost to you, receive a portion of sales if you purchase a product through a link in this article.

A lot of work on the topic of aging looks at dealing with symptoms of aging, rather than the causes. And, that’s worthy too! Those symptoms often do need addressing. But this book is about treating the causes.

Dr. Hyman outlines:

- How and why we age

- The root causes of aging

- The ten hallmarks of aging

From there, we go on to learn about the foundations of longevity, and balancing our seven core biological systems:

- Nutrition, digestion, and the microbiome

- Immune and inflammatory system

- Cellular energy

- Biotransformation and elimination/detoxification*

- Hormones, neurotransmitters, and other signalling molecules

- Circulation and lymphatic flow

- Structural health, from muscle and bones to cells and tissues

*This isn’t about celery juice fasts and the like; this talking about the work your kidneys, liver, and other organs do

The book goes on to detail how, precisely, with practical actionable advices, to optimize and take care of each of those systems.

All in all: if you want a great foundational understanding of aging and how to slow it to increase your healthy lifespan, this is a very respectable option.

Click here to get your copy of “Young Forever” from Amazon today!

Don’t Forget…

Did you arrive here from our newsletter? Don’t forget to return to the email to continue learning!

Learn to Age Gracefully

Join the 98k+ American women taking control of their health & aging with our 100% free (and fun!) daily emails:

-

Clams vs Oysters – Which is Healthier?

10almonds is reader-supported. We may, at no cost to you, receive a portion of sales if you purchase a product through a link in this article.

Our Verdict

When comparing clams to oysters, we picked the clams.

Why?

Considering the macros first, clams have more than 2x the protein, while oysters have nearly 2x the fat, of which, a little over 5x the saturated fat. So, in all accounts, clam is the winner here.

In terms of vitamins, clams have more of vitamins A, B1, B2, B3, B5, B6, B7, B9, B12, and C, while oysters are not higher in any vitamins. Another win for clams.

The category of minerals is more balanced; clams are higher in manganese, phosphorus, potassium, and selenium, while oysters are higher in copper, iron, magnesium, and zinc. This makes for a 4:4 tie, though it’s worth noting that the margin of difference for zinc is very large, so that can be an argument for oysters.

Nevertheless, adding up the sections makes for a clear win for clams.

A quick aside on “are oysters an aphrodisiac?”:

That zinc content is probably largely responsible for oysters’ reputation as an aphrodisiac, and zinc is important in the synthesis of both estrogen and testosterone. However, as the synthesis is not instant, and those sex hormones rise most in the morning (around 8am to 9am), to enjoy aphrodisiac benefits it’d be more sensible, on a biochemical level, to eat oysters one day, and then have morning sex the next day when those hormones are peaking. That said, while testosterone is the main driver of male libido, progesterone is usually more relevant for women’s, and unlike estrogen, progesterone usually peaks around 10pm to 2am, and is uninfluenced by having just eaten oysters.

So, in what way, if any, could oysters be responsible for libido in women? Well, the zinc is still important in energy metabolism, so that’s a factor, and also, we might hypothesize that oysters’ high saturated fat and cholesterol content may increase blood pressure which, while not fabulous for the health in general, may be considered desirable in the bedroom since the clitoris is anatomically analogous to the penis, and—while estrogen vs testosterone makes differences to the nervous system down there that are beyond the scope of today’s article—also enjoys localized increased blood pressure (and thus, a flushing response and resultant engorgement) during arousal.

Want to learn more?

You might like to read:

Does Eating Shellfish Really Contribute To Gout? ← short answer is: it can if consumed frequently over a long period of time, but that risk factor is greatly overstated, compared to some other risk factors

Take care!

Don’t Forget…

Did you arrive here from our newsletter? Don’t forget to return to the email to continue learning!

Learn to Age Gracefully

Join the 98k+ American women taking control of their health & aging with our 100% free (and fun!) daily emails: