Dates vs Banana – Which is Healthier?

10almonds is reader-supported. We may, at no cost to you, receive a portion of sales if you purchase a product through a link in this article.

Our Verdict

When comparing dates to banana, we picked the dates.

Why?

It was close, and bananas do have some strengths too! We pitted these two against each other as they’re both sweet fruits often used as a sweetening and consistency-altering ingredient in desserts and sweet snacks, so if you’re making a choice between them, here are the things to consider:

In terms of macros, dates have more than 3x the fiber, more than 2x the protein, and a little over 3x the carbs. You may be wondering how this adds up in terms of glycemic index: dates have the lower GI. So, we pick dates, here, for that reason and overall nutritional density too.

When it comes to vitamins, bananas have their moment, albeit barely: dates have more of vitamins B1, B3, B5, and K, while bananas have more of vitamins A, B6, C, E, and choline, making for a marginal victory for bananas in this category.

Looking at minerals next, however, it’s quite a different story: dates have more calcium, copper, iron, magnesium, phosphorus, potassium, selenium, and zinc, while bananas are not higher in any mineral. No, not even potassium, for which they are famous—dates have nearly 2x more potassium than bananas.

Adding up these sections makes for a clear win for dates in general!

Enjoy either/both, but dates are the more nutritious snack/ingredient.

Want to learn more?

You might like to read:

From Apples to Bees, and High-Fructose Cs: Which Sugars Are Healthier, And Which Are Just The Same?

Take care!

Don’t Forget…

Did you arrive here from our newsletter? Don’t forget to return to the email to continue learning!

Recommended

Learn to Age Gracefully

Join the 98k+ American women taking control of their health & aging with our 100% free (and fun!) daily emails:

-

5 Things To Know About Passive Suicidal Ideation

10almonds is reader-supported. We may, at no cost to you, receive a portion of sales if you purchase a product through a link in this article.

If you’ve ever wanted to go to sleep and never wake up, or have some accident/incident/illness take you with no action on your part, or a loved one has ever expressed such thoughts/feelings to you… Then this video is for you. Dr. Scott Eilers explains:

Tired of living

We’ll not keep them a mystery; here are the five things that Dr. Eilers wants us to know about passive suicidal ideation:

- What it is: a desire for something to end your life without taking active steps. While it may seem all too common, it’s not necessarily inevitable or unchangeable.

- What it means in terms of severity: it isn’t a clear indicator of how severe someone’s depression is. It doesn’t necessarily mean that the person’s depression is mild; it can be severe even without active suicidal thoughts, or indeed, suicidality at all.

- What it threatens: although passive suicidal ideation doesn’t usually involve active planning, it can still be dangerous. Over time, it can evolve into active suicidal ideation or lead to risky behaviors.

- What it isn’t: passive suicidal ideation is different from intrusive thoughts, which are unwanted, distressing thoughts about death. The former involves a desire for death, while the latter does not.

- What it doesn’t have to be: passive suicidal ideation is often a symptom of underlying depression or a mood disorder, which can be treated through therapy, medication, or a combination of both. Seeking treatment is crucial and can be life-changing.

For more on all of the above, here’s Dr. Eilers with his own words:

Click Here If The Embedded Video Doesn’t Load Automatically!

Want to learn more?

You might also like to read:

- The Mental Health First Aid You’ll Hopefully Never Need ← about depression generally

- How To Stay Alive (When You Really Don’t Want To) ← about suicidality specifically

Take care!

Share This Post

-

In the Realm of Hungry Ghosts – by Dr. Gabor Maté

10almonds is reader-supported. We may, at no cost to you, receive a portion of sales if you purchase a product through a link in this article.

We’ve reviewed books by Dr. Maté before, and this one’s about addiction. We’ve reviewed books about addiction before too, so what makes this one different?

Wow, is this one so different. Most books about addiction are about “beating” it. Stop drinking, quit sugar, etc. And, that’s all well and good. It is definitely good to do those things. But this one’s about understanding it, deeply. Because, as Dr. Maté makes very clear, “there, but for the grace of epigenetics and environmental factors, go we”.

Indeed, most of us will have addictions; they’re (happily) just not too problematic for most of us, being either substances that are not too harmful (e.g. coffee), or behavioral addictions that aren’t terribly impacting our lives (e.g. Dr. Maté’s compulsion to keep buying more classical music, which he then tries to hide from his wife).

The book does also cover a lot of much more serious addictions, the kind that have ruined lives, and the kind that definitely didn’t need to, if people had been given the right kind of help—instead of, all too often, they got the opposite.

Perhaps the greatest value of this book is that; understanding what creates addiction in the first place, what maintains it, and what help people actually need.

Bottom line: if you’d like more insight into the human aspect of addiction without getting remotely wishy-washy, this book is probably the best one out there.

Share This Post

-

Gluten: What’s The Truth?

10almonds is reader-supported. We may, at no cost to you, receive a portion of sales if you purchase a product through a link in this article.

Gluten: What’s The Truth?

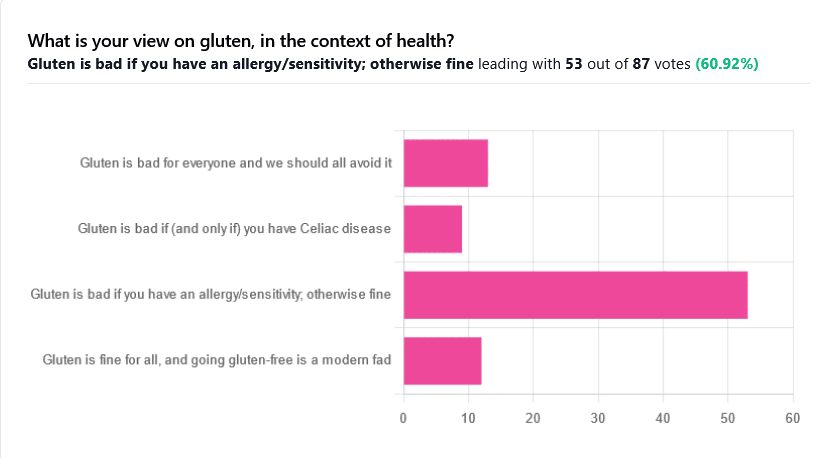

We asked you for your health-related view of gluten, and got the above spread of results. To put it simply:

Around 60% of voters voted for “Gluten is bad if you have an allergy/sensitivity; otherwise fine”

The rest of the votes were split fairly evenly between the other three options:

- Gluten is bad for everyone and we should avoid it

- Gluten is bad if (and only if) you have Celiac disease

- Gluten is fine for all, and going gluten-free is a modern fad

First, let’s define some terms so that we’re all on the same page:

What is gluten?

Gluten is a category of protein found in wheat, barley, rye, and triticale. As such, it’s not one single compound, but a little umbrella of similar compounds. However, for the sake of not making this article many times longer, we’re going to refer to “gluten” without further specification.

What is Celiac disease?

Celiac disease is an autoimmune disease. Like many autoimmune diseases, we don’t know for sure how/why it occurs, but a combination of genetic and environmental factors have been strongly implicated, with the latter putatively including overexposure to gluten.

It affects about 1% of the world’s population, and people with Celiac disease will tend to respond adversely to gluten, notably by inflammation of the small intestine and destruction of enterocytes (the cells that line the wall of the small intestine). This in turn causes all sorts of other problems, beyond the scope of today’s main feature, but suffice it to say, it’s not pleasant.

What is an allergy/intolerance/sensitivity?

This may seem basic, but a lot of people conflate allergy/intolerance/sensitivity, so:

- An allergy is when the body mistakes a harmless substance for something harmful, and responds inappropriately. This can be mild (e.g. allergic rhinitis, hayfever) or severe (e.g. peanut allergy), and as such, responses can vary from “sniffly nose” to “anaphylactic shock and death”.

- In the case of a wheat allergy (for example), this is usually somewhere between the two, and can for example cause breathing problems after ingesting wheat or inhaling wheat flour.

- An intolerance is when the body fails to correctly process something it should be able to process, and just ejects it half-processed instead.

- A common and easily demonstrable example is lactose intolerance. There isn’t a well-defined analog for gluten, but gluten intolerance is nonetheless a well-reported thing.

- A sensitivity is when none of the above apply, but the body nevertheless experiences unpleasant symptoms after exposure to a substance that should normally be safe.

- In the case of gluten, this is referred to as non-Celiac gluten sensitivity

A word on scientific objectivity: at 10almonds we try to report science as objectively as possible. Sometimes people have strong feelings on a topic, especially if it is polarizing.

Sometimes people with a certain condition feel constantly disbelieved and mocked; sometimes people without a certain condition think others are imagining problems for themselves where there are none.

We can’t diagnose anyone or validate either side of that, but what we can do is report the facts as objectively as science can lay them out.

Gluten is fine for all, and going gluten-free is a modern fad: True or False?

Definitely False, Celiac disease is a real autoimmune disease that cannot be faked, and allergies are also a real thing that people can have, and again can be validated in studies. Even intolerances have scientifically measurable symptoms and can be tested against nocebo.

See for example:

- Epidemiology and clinical presentations of Celiac disease

- Severe forms of food allergy that can precipitate allergic emergencies

- Properties of gluten intolerance: gluten structure, evolution, and pathogenicity

However! It may not be a modern fad, so much as a modern genuine increase in incidence.

Widespread varieties of wheat today contain a lot more gluten than wheat of ages past, and many other molecular changes mean there are other compounds in modern grains that never even existed before.

However, the health-related impact of these (novel proteins and carbohydrates) is currently still speculative, and we are not in the business of speculating, so we’ll leave that as a “this hasn’t been studied enough to comment yet but we recognize it could potentially be a thing” factor.

Gluten is bad if (and only if) you have Celiac disease: True or False?

Definitely False; allergies for example are well-evidenced as real; same facts as we discussed/linked just above.

Gluten is bad for everyone and we should avoid it: True or False?

False, tentatively and contingently.

First, as established, there are people with clinically-evidenced Celiac disease, wheat allergy, or similar. Obviously, they should avoid triggering those diseases.

What about the rest of us, and what about those who have non-Celiac gluten sensitivity?

Clinical testing has found that of those reporting non-Celiac gluten sensitivity, nocebo-controlled studies validate that diagnosis in only a minority of cases.

In the following study, for example, only 16% of those reporting symptoms showed them in the trials, and 40% of those also showed a nocebo response (i.e., like placebo, but a bad rather than good effect):

This one, on the other hand, found that positive validations of diagnoses were found to be between 7% and 77%, depending on the trial, with an average of 30%:

Re-challenge Studies in Non-celiac Gluten Sensitivity: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis

In other words: non-Celiac gluten sensitivity is a thing, and/but may be over-reported, and/but may be in some part exacerbated by psychosomatic effect.

Note: psychosomatic effect does not mean “imagining it” or “all in your head”. Indeed, the “soma” part of the word “psychosomatic” has to do with its measurable effect on the rest of the body.

For example, while pain can’t be easily objectively measured, other things, like inflammation, definitely can.

As for everyone else? If you’re enjoying your wheat (or similar) products, it’s well-established that they should be wholegrain for the best health impact (fiber, a positive for your health, rather than white flour’s super-fast metabolites padding the liver and causing metabolic problems).

Wheat itself may have other problems, for example FODMAPs, amylase trypsin inhibitors, and wheat germ agglutinins, but that’s “a wheat thing” rather than “a gluten thing”.

That’s beyond the scope of today’s main feature, but you might want to check out today’s featured book!

For a final scientific opinion on this last one, though, here’s what a respected academic journal of gastroenterology has to say:

From coeliac disease to noncoeliac gluten sensitivity; should everyone be gluten-free?

Share This Post

Related Posts

-

Slowing the Progression of Cataracts

10almonds is reader-supported. We may, at no cost to you, receive a portion of sales if you purchase a product through a link in this article.

Understanding Cataracts

Cataracts are natural and impact everyone.

That’s a bit of a daunting opening line, but as Dr. Michele Lee, a board-certified ophthalmologist, explains, cataracts naturally develop with age, and can be accelerated by factors such as trauma, certain medications, and specific eye conditions.

We know how important your vision is to you (we’ve had great feedback about the book Vision for Life) as well as our articles on how glasses impact your eyesight and the effects of using eye drops.

While complete prevention isn’t possible, steps such as those mentioned below can be taken to slow their progression.

Here is an overview of the video’s first 3 takeaways. You can watch the whole video below.

Protect Your Eyes from Sunlight

Simply put, UV light damages lens proteins, which (significantly) contributes to cataracts. Wearing sunglasses can supposedly prevent up to 20% of cataracts caused by UV exposure.

Moderate Alcohol Consumption

We all, at some level, know that alcohol consumption doesn’t do us any good. Your eye health isn’t an exception to the rule; alcohol has been shown to contribute to cataract development.

If you’re looking at reducing your alcohol use, try reading this guide on lowering, or eradicating, alcohol consumption.

Avoid Smoking

Smokers are 2-3 times more likely to develop cataracts. Additionally, ensure good ventilation while cooking to avoid exposure to harmful indoor smoke.

See all 5 steps in the below video:

How was the video? If you’ve discovered any great videos yourself that you’d like to share with fellow 10almonds readers, then please do email them to us!

Don’t Forget…

Did you arrive here from our newsletter? Don’t forget to return to the email to continue learning!

Learn to Age Gracefully

Join the 98k+ American women taking control of their health & aging with our 100% free (and fun!) daily emails:

-

Bright Line Eating – by Dr. Susan Peirce Thompson

10almonds is reader-supported. We may, at no cost to you, receive a portion of sales if you purchase a product through a link in this article.

This is a great title! It’s a great book too, but let’s talk about the title for a moment:

The “Bright Line” referenced (often used in the plural within the book) is the line one draws between what one will and will not do. It’s a line one doesn’t cross, and it’s a bright line, because it’s not a case of “oh woe is me I cannot have the thing”, but rather “oh yay is me for I being joyously healthy”.

And as for living happy, thin, and free? The author makes clear that “thin” is only a laudable goal if it’s bookended by “happy” and “free”. Eating things because we want to, and being happy about our choices.

To this end, while some of the book is about nutrition (and for example the strong recommendation to make the first “bright lines” one draws cutting out sugar and flour), the majority of it is about the psychology of eating.

This includes, hunger and satiety, willpower and lack thereof, disordered eating and addictions, body image issues and social considerations, the works. She realizes and explains, that if being healthy were just a matter of the right diet plan, everyone would be healthy. But it’s not; our eating behaviors don’t exist in a vacuum, and there’s a lot more to consider.

Despite all the odds, however, this is a cheerful and uplifting book throughout, while dispensing very practical, well-evidenced methods for getting your brain to get your body to do what you want it to.

Bottom line: this isn’t your average diet book, and it’s not just a motivational pep talk either. It’s an enjoyable read that’s also full of science and can make a huge difference to how you see food.

Click here to check out Bright Line Eating, and enjoy life, healthily!

Don’t Forget…

Did you arrive here from our newsletter? Don’t forget to return to the email to continue learning!

Learn to Age Gracefully

Join the 98k+ American women taking control of their health & aging with our 100% free (and fun!) daily emails:

-

Chia vs Sesame – Which is Healthier?

10almonds is reader-supported. We may, at no cost to you, receive a portion of sales if you purchase a product through a link in this article.

Our Verdict

When comparing chia to sesame, we picked the chia.

Why?

This might not be a shocking decision; after all, chia has an awesome reputation, and it’s well deserved. But sesame seeds are great too, and definitely have their strengths!

In terms of macros, chia seeds have more than 3x the fiber (which is lots) for a little over 1.5x the carbs (giving it the lower glycemic index), and about equal protein. The matter of fats is also interesting: sesame seeds have nearly 2x the fat, but chia seeds have the better fats profile, with less saturated fat and more omega-3s. All in all, a sound win for chia in this category!

In the category of vitamins, chia seeds have more of vitamins B3, C, E, and choline, while sesame seeds have more of vitamins B1, B2, and B9. A more marginal win for chia here.

When it comes to minerals, chia seeds have more phosphorus, manganese, and selenium, while sesame seeds have more calcium, copper, iron, and zinc, making it a marginal win for sesame seeds this time!

Adding up the sections make for an overall win for chia (especially if we were to consider the macros category for its full weight, given the importance of those components, but it’s still a 2:1 win for chia even if we pay no attention to that), but by all means enjoy either or both; diversity is good!

Want to learn more?

You might like:

The Tiniest Seeds With The Most Value: If You’re Not Taking Chia, You’re Missing Out

Enjoy!

Don’t Forget…

Did you arrive here from our newsletter? Don’t forget to return to the email to continue learning!

Learn to Age Gracefully

Join the 98k+ American women taking control of their health & aging with our 100% free (and fun!) daily emails: