Health Care AI, Intended To Save Money, Turns Out To Require a Lot of Expensive Humans

10almonds is reader-supported. We may, at no cost to you, receive a portion of sales if you purchase a product through a link in this article.

Preparing cancer patients for difficult decisions is an oncologist’s job. They don’t always remember to do it, however. At the University of Pennsylvania Health System, doctors are nudged to talk about a patient’s treatment and end-of-life preferences by an artificially intelligent algorithm that predicts the chances of death.

But it’s far from being a set-it-and-forget-it tool. A routine tech checkup revealed the algorithm decayed during the covid-19 pandemic, getting 7 percentage points worse at predicting who would die, according to a 2022 study.

There were likely real-life impacts. Ravi Parikh, an Emory University oncologist who was the study’s lead author, told KFF Health News the tool failed hundreds of times to prompt doctors to initiate that important discussion — possibly heading off unnecessary chemotherapy — with patients who needed it.

He believes several algorithms designed to enhance medical care weakened during the pandemic, not just the one at Penn Medicine. “Many institutions are not routinely monitoring the performance” of their products, Parikh said.

Algorithm glitches are one facet of a dilemma that computer scientists and doctors have long acknowledged but that is starting to puzzle hospital executives and researchers: Artificial intelligence systems require consistent monitoring and staffing to put in place and to keep them working well.

In essence: You need people, and more machines, to make sure the new tools don’t mess up.

“Everybody thinks that AI will help us with our access and capacity and improve care and so on,” said Nigam Shah, chief data scientist at Stanford Health Care. “All of that is nice and good, but if it increases the cost of care by 20%, is that viable?”

Government officials worry hospitals lack the resources to put these technologies through their paces. “I have looked far and wide,” FDA Commissioner Robert Califf said at a recent agency panel on AI. “I do not believe there’s a single health system, in the United States, that’s capable of validating an AI algorithm that’s put into place in a clinical care system.”

AI is already widespread in health care. Algorithms are used to predict patients’ risk of death or deterioration, to suggest diagnoses or triage patients, to record and summarize visits to save doctors work, and to approve insurance claims.

If tech evangelists are right, the technology will become ubiquitous — and profitable. The investment firm Bessemer Venture Partners has identified some 20 health-focused AI startups on track to make $10 million in revenue each in a year. The FDA has approved nearly a thousand artificially intelligent products.

Evaluating whether these products work is challenging. Evaluating whether they continue to work — or have developed the software equivalent of a blown gasket or leaky engine — is even trickier.

Take a recent study at Yale Medicine evaluating six “early warning systems,” which alert clinicians when patients are likely to deteriorate rapidly. A supercomputer ran the data for several days, said Dana Edelson, a doctor at the University of Chicago and co-founder of a company that provided one algorithm for the study. The process was fruitful, showing huge differences in performance among the six products.

It’s not easy for hospitals and providers to select the best algorithms for their needs. The average doctor doesn’t have a supercomputer sitting around, and there is no Consumer Reports for AI.

“We have no standards,” said Jesse Ehrenfeld, immediate past president of the American Medical Association. “There is nothing I can point you to today that is a standard around how you evaluate, monitor, look at the performance of a model of an algorithm, AI-enabled or not, when it’s deployed.”

Perhaps the most common AI product in doctors’ offices is called ambient documentation, a tech-enabled assistant that listens to and summarizes patient visits. Last year, investors at Rock Health tracked $353 million flowing into these documentation companies. But, Ehrenfeld said, “There is no standard right now for comparing the output of these tools.”

And that’s a problem, when even small errors can be devastating. A team at Stanford University tried using large language models — the technology underlying popular AI tools like ChatGPT — to summarize patients’ medical history. They compared the results with what a physician would write.

“Even in the best case, the models had a 35% error rate,” said Stanford’s Shah. In medicine, “when you’re writing a summary and you forget one word, like ‘fever’ — I mean, that’s a problem, right?”

Sometimes the reasons algorithms fail are fairly logical. For example, changes to underlying data can erode their effectiveness, like when hospitals switch lab providers.

Sometimes, however, the pitfalls yawn open for no apparent reason.

Sandy Aronson, a tech executive at Mass General Brigham’s personalized medicine program in Boston, said that when his team tested one application meant to help genetic counselors locate relevant literature about DNA variants, the product suffered “nondeterminism” — that is, when asked the same question multiple times in a short period, it gave different results.

Aronson is excited about the potential for large language models to summarize knowledge for overburdened genetic counselors, but “the technology needs to improve.”

If metrics and standards are sparse and errors can crop up for strange reasons, what are institutions to do? Invest lots of resources. At Stanford, Shah said, it took eight to 10 months and 115 man-hours just to audit two models for fairness and reliability.

Experts interviewed by KFF Health News floated the idea of artificial intelligence monitoring artificial intelligence, with some (human) data whiz monitoring both. All acknowledged that would require organizations to spend even more money — a tough ask given the realities of hospital budgets and the limited supply of AI tech specialists.

“It’s great to have a vision where we’re melting icebergs in order to have a model monitoring their model,” Shah said. “But is that really what I wanted? How many more people are we going to need?”

KFF Health News is a national newsroom that produces in-depth journalism about health issues and is one of the core operating programs at KFF—an independent source of health policy research, polling, and journalism. Learn more about KFF.

Subscribe to KFF Health News’ free Morning Briefing.

This article first appeared on KFF Health News and is republished here under a Creative Commons license.

Don’t Forget…

Did you arrive here from our newsletter? Don’t forget to return to the email to continue learning!

Recommended

Learn to Age Gracefully

Join the 98k+ American women taking control of their health & aging with our 100% free (and fun!) daily emails:

-

Tech Bliss – by Clo S., MSc.

10almonds is reader-supported. We may, at no cost to you, receive a portion of sales if you purchase a product through a link in this article.

The popular idea of a “digital detox” is simple enough, “just unplug!”, they say.

But here in the real world, not only is that often not practical for many of us, it may not always even be entirely desirable. The Internet (and our devices with all their bells and whistles) can be a source of education, joy, and connection!

So, how to find out what’s good for us and what’s not, in our daily digital practices? Clo. S. has answers… Or rather, experiments for us to do and find out for ourselves.

These experiments range from the purely practical “try this to streamline your experience” to the more personal “how does this thing make you feel?”. A lot of the experiments will be performed via your digital devices—some, without! Others are about online interpersonal dynamics, be they one-on-one or navigating a world in which it seems everyone is out to get us, our outrage, and/or our money. Still yet others are about optimizing what you do get from the parts of your digital experience that are enriching for you.

As the title suggests, there are 30 experiments, and it’s not a stretch to do them one per day for a month. But, as the author notes, it’s by no means necessary to do them like that; it’s a workbook and reference guide, not a to-do list!

(On the topic of it being a reference guide…There’s also an extensive tools directory towards the end!)

In short: this is a great book for optimizing your online experience—whatever that might mean for you personally; you can decide for yourself along the way!

Click here to get a copy of Tech Bliss: 30 Experiments For Your Digital Wellness today!

Share This Post

-

Sometimes, Perfect Isn’t Practical!

10almonds is reader-supported. We may, at no cost to you, receive a portion of sales if you purchase a product through a link in this article.

It’s Q&A Day at 10almonds!

Have a question or a request? We love to hear from you!

In cases where we’ve already covered something, we might link to what we wrote before, but will always be happy to revisit any of our topics again in the future too—there’s always more to say!

As ever: if the question/request can be answered briefly, we’ll do it here in our Q&A Thursday edition. If not, we’ll make a main feature of it shortly afterwards!

So, no question/request too big or small

❝10 AM breakfast is not realistic for most. What’s wrong with 8 AM and Evening me at 6. Don’t quite understand the differentiation.❞

(for reference, this is about our “Breakfasting For Health?” main feature)

It’s not terrible to do it the way you suggest It’s just not optimal, either, that’s all!

Breakfasting at 08:00 and then dining at 18:00 is ten hours apart, so no fasting benefits between those. Let’s say you take half an hour to eat dinner, then eat nothing again until breakfast, that’s 18:30 to 08:00, so that’s 13½ hours fasting. You’ll recall that fasting benefits start at 12 hours into the fast, so that means you’d only get 1½ hours of fasting benefits.

As for breakfasting at 08:00 regardless of intermittent fasting considerations, the reason for the conclusion of around 10:00 being optimal, is based on when our body is geared up to eat breakfast and get the most out of that, which the body can’t do immediately upon waking. So if you wake and get sunlight at 08:30, get a little moderate exercise, then by 10:00 your digestive system will be perfectly primed to get the most out of breakfast.

However! This is entirely based on you waking and getting sunlight at 08:30.

So, iff you wake and get sunlight at 06:30, then in that case, breakfasting at 08:00 would give the same benefits as described above. What’s important is the 1½ hour priming-time.

Writer’s note: our hope here is always to be informational, not prescriptive. Take what works for you; ignore what doesn’t fit your lifestyle.

I personally practice intermittent fasting for about 21hrs/day. I breakfast (often on nuts and perhaps a little salad) around 16:00, and dine at around 18:00ish, giving myself a little wiggleroom. I’m not religious about it and will slide it if necessary.

As you can see: that makes what is nominally my breakfast practically a pre-dinner snack, and I clearly ignore the “best to eat in the morning” rule because that’s not consistent with my desire to have a family dinner together in the evening while still practicing the level of fasting that I prefer.

Science is science, and that’s what we report here. How we apply it, however, is up to us all as individuals!

Enjoy!

Share This Post

-

What’s the difference between a food allergy and an intolerance?

10almonds is reader-supported. We may, at no cost to you, receive a portion of sales if you purchase a product through a link in this article.

At one time or another, you’ve probably come across someone who is lactose intolerant and might experience some unpleasant gut symptoms if they have dairy. Maybe it’s you – food intolerances are estimated to affect up to 25% of Australians.

Meanwhile, cow’s milk allergy is one of the most common food allergies in infants and young children, affecting around one in 100 infants.

But what’s the difference between food allergies and food intolerances? While they might seem alike, there are some fundamental differences between the two.

Feel good studio/Shutterstock What is an allergy?

Australia has one of the highest rates of food allergies in the world. Food allergies can develop at any age but are more common in children, affecting more than 10% of one-year-olds and 6% of children at age ten.

A food allergy happens when the body’s immune system mistakenly reacts to certain foods as if they were dangerous. The most common foods that trigger allergies include eggs, peanuts and other nuts, milk, shellfish, fish, soy and wheat.

Mild to moderate signs of food allergy include a swollen face, lips or eyes; hives or welts on your skin; or vomiting. A severe allergic reaction (called anaphylaxis) can cause trouble breathing, persistent dizziness or collapse.

What is an intolerance?

Food intolerances (sometimes called non-allergic reactions) are also reactions to food, but they don’t involve your immune system.

For example, lactose intolerance is a metabolic condition that happens when the body doesn’t produce enough lactase. This enzyme is needed to break down the lactose (a type of sugar) in dairy products.

Food intolerances can also include reactions to natural chemicals in foods (such as salicylates, found in some fruits, vegetables, herbs and spices) and problems with artificial preservatives or flavour enhancers.

Lactose intolerance is caused by a problem with breaking down lactose in milk. Pormezz/Shutterstock Symptoms of food intolerances can include an upset stomach, headaches and fatigue, among others.

Food intolerances don’t cause life-threatening reactions (anaphylaxis) so are less dangerous than allergies in the short term, although they can cause problems in the longer term such as malnutrition.

We don’t know a lot about how common food intolerances are, but they appear to be more commonly reported than allergies. They can develop at any age.

It can be confusing

Some foods, such as peanuts and tree nuts, are more often associated with allergy. Other foods or ingredients, such as caffeine, are more often associated with intolerance.

Meanwhile, certain foods, such as cow’s milk and wheat or gluten (a protein found in wheat, rye and barley), can cause both allergic and non-allergic reactions in different people. But these reactions, even when they’re caused by the same foods, are quite different.

For example, children with a cow’s milk allergy can react to very small amounts of milk, and serious reactions (such as throat swelling or difficulty breathing) can happen within minutes. Conversely, many people with lactose intolerance can tolerate small amounts of lactose without symptoms.

There are other differences too. Cow’s milk allergy is more common in children, though many infants will grow out of this allergy during childhood.

Lactose intolerance is more common in adults, but can also sometimes be temporary. One type of lactose intolerance, secondary lactase deficiency, can be caused by damage to the gut after infection or with medication use (such as antibiotics or cancer treatment). This can go away by itself when the underlying condition resolves or the person stops using the relevant medication.

Whether an allergy or intolerance is likely to be lifelong depends on the food and the reason that the child or adult is reacting to it.

Allergies to some foods, such as milk, egg, wheat and soy, often resolve during childhood, whereas allergies to nuts, fish or shellfish, often (but not always) persist into adulthood. We don’t know much about how likely children are to grow out of different types of food intolerances.

How do you find out what’s wrong?

If you think you may have a food allergy or intolerance, see a doctor.

Allergy tests help doctors find out which foods might be causing your allergic reactions (but can’t diagnose food intolerances). There are two common types: skin prick tests and blood tests.

In a skin prick test, doctors put tiny amounts of allergens (the things that can cause allergies) on your skin and make small pricks to see if your body reacts.

A blood test checks for allergen-specific immunoglobulin E (IgE) antibodies in your blood that show if you might be allergic to a particular food.

Blood tests can help diagnose allergies. RossHelen/Shutterstock Food intolerances can be tricky to figure out because the symptoms depend on what foods you eat and how much. To diagnose them, doctors look at your health history, and may do some tests (such as a breath test). They may ask you to keep a record of foods you eat and timing of symptoms.

A temporary elimination diet, where you stop eating certain foods, can also help to work out which foods you might be intolerant to. But this should only be done with the help of a doctor or dietitian, because eliminating particular foods can lead to nutritional deficiencies, especially in children.

Is there a cure?

There’s currently no cure for food allergies or intolerances. For allergies in particular, it’s important to strictly avoid allergens. This means reading food labels carefully and being vigilant when eating out.

However, researchers are studying a treatment called oral immunotherapy, which may help some people with food allergies become less sensitive to certain foods.

Whether you have a food allergy or intolerance, your doctor or dietitian can help you to make sure you’re eating the right foods.

Victoria Gibson, a Higher Degree by Research student and Research Officer at the School of Nursing, Midwifery and Social Work at the University of Queensland, and Rani Scott-Farmer, a Senior Research Assistant at the University of Queensland, contributed to this article.

Jennifer Koplin, Group Leader, Childhood Allergy & Epidemiology, The University of Queensland and Desalegn Markos Shifti, Postdoctoral Research Fellow, Child Health Research Centre, Faculty of Medicine, The University of Queensland

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Share This Post

Related Posts

-

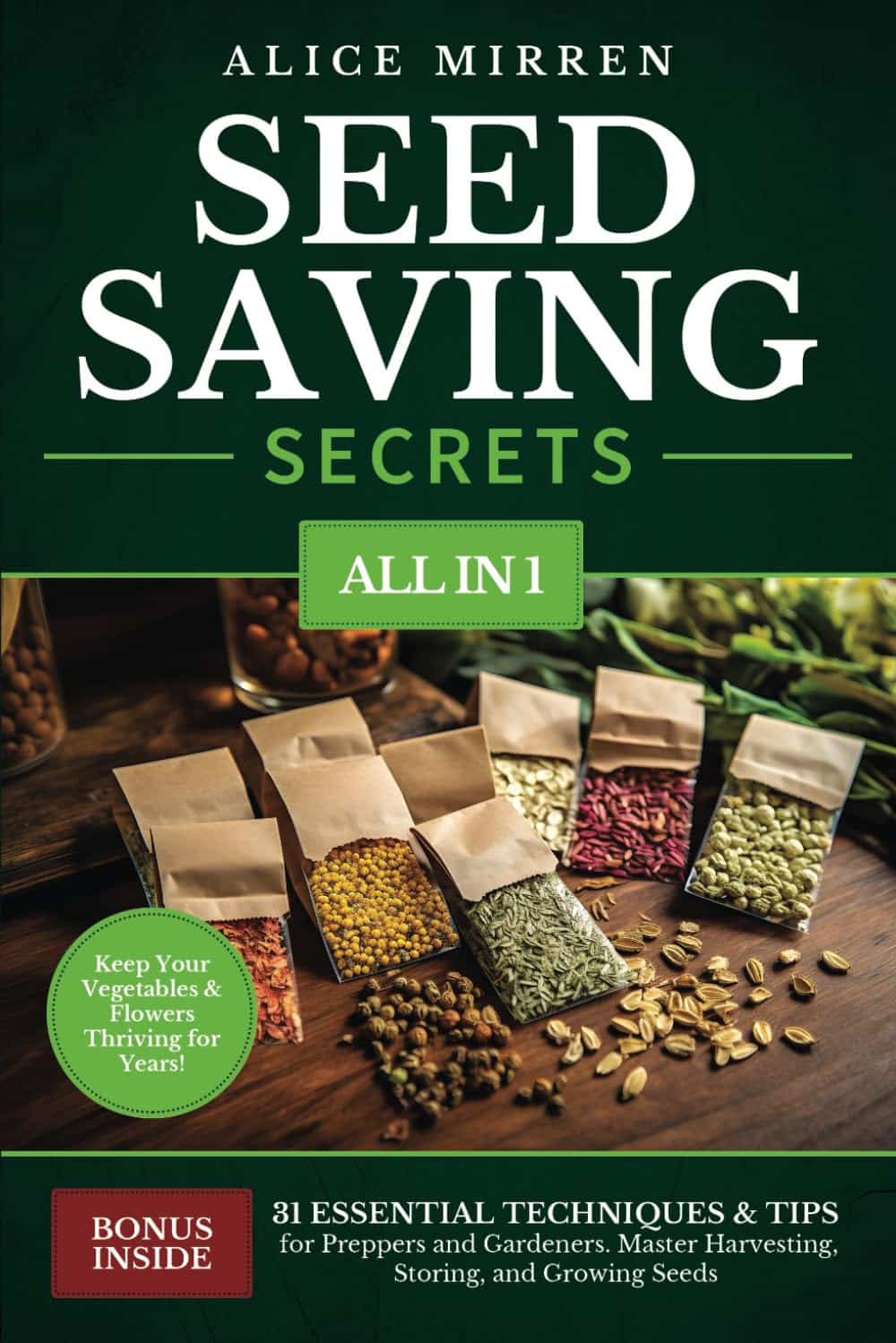

Seed Saving Secrets – by Alice Mirren

10almonds is reader-supported. We may, at no cost to you, receive a portion of sales if you purchase a product through a link in this article.

We all know that home-grown is best, and yet many of us are not exactly farmers (this reviewer tries with mixed results—hardy crops survive; others, not so much). While it’s easy to blame the acidic soil, the harsh climate, or not having enough time and money (this reviewer blames all of the above), the fact remains that a skilled gardener can produce a good crop in any conditions.

That’s where this book helps; right from the beginning, from the seeds. Have you ever bought a pack of seeds, excitedly sown them, and then had a germination rate of zero or something close to that (this reviewer has)?

Alice Mirren takes us on a tour of how to save seeds from plants you know are regionally viable (not the product of some vast globalized industry that doesn’t know you live in an ancient bog with a cold south-east wind blowing in from Siberia), and then how to care for and curate them, how to store them for future years, how to keep a self-perpetuating seed bank.

She goes beyond that, though. Regular 10almonds readers might remember about the supercentenarian “Blue Zones”, and how big factors in healthy longevity include community and purpose; Mirren advocates for organizing community seed banks, which will also mean that everyone (including you) has access to much more diverse seeds, and when it comes to the perils of natural selection, diversity means survival. Otherwise, if you have just one seed type, a single blight can wipe out everything pretty much overnight.

Bottom line: if you grow your own food or would like to, this is a “bible of…” level book that you absolutely should have to hand.

Click here to check out Seed Saving Secrets, and see the results in your kitchen and on your plate!

Don’t Forget…

Did you arrive here from our newsletter? Don’t forget to return to the email to continue learning!

Learn to Age Gracefully

Join the 98k+ American women taking control of their health & aging with our 100% free (and fun!) daily emails:

-

The Path to Longevity – by Dr. Luigi Fontana

10almonds is reader-supported. We may, at no cost to you, receive a portion of sales if you purchase a product through a link in this article.

We’ve reviewed other “expand your healthspan” books, and while they’re good (or else we wouldn’t include them), this is top-tier, up there with Dr. Greger’s books while being more accessible (more on this later).

This book is far more informational than opinionated, and while some reviewers have described the book as motivating them, that’s not at all the tone, and it’s clear that (beyond hoping for the reader to have to information to promote a long healthy life), the author has no particular agenda to push.

One example: while he gives a whole-foods, plant-based diet a “A+” rating, he puts the (often meat/fish-heavy) paleo diet at a close “A-“, depending on the animal products chosen (which can swing it a lot, and he discusses this in some detail).

In the category of criticism… This reviewer has none. Sometimes it seemed something was going unaddressed, but it would be addressed later.

Stylistically, the text is easy-reading and/but has a lot of references to hard science, complete with charts, diagrams, and so forth. The impression that this reviewer got is that Dr. Fontana took pains to convey as much science as possible, with (unlike Dr. Greger) as little jargon as possible. And that goes a long way.

Bottom line: if you’re looking for a “healthy aging” book that has a lot more science than “copy the Blue Zone supercentenarians and hope” without being so scientifically dense as “How Not To Die” or “How Not To Age“, then this is the book for you.

Click here to check out The Path to Longevity, and optimize the path you take!

Don’t Forget…

Did you arrive here from our newsletter? Don’t forget to return to the email to continue learning!

Learn to Age Gracefully

Join the 98k+ American women taking control of their health & aging with our 100% free (and fun!) daily emails:

-

Human, Bird, or Dog Waste? Scientists Parsing Poop To Aid DC’s Forgotten River

10almonds is reader-supported. We may, at no cost to you, receive a portion of sales if you purchase a product through a link in this article.

KFF Health News Peggy Girshman reporting fellow Jackie Fortiér joined a boat tour to spotlight a review of microbes in the Anacostia River, a step toward making the river healthier and swimmable. The story was featured on WAMU’s “Health Hub” on Feb. 26.

On a bright October day, high schoolers from Francis L. Cardozo Education Campus piled into a boat on the Anacostia River in Washington, D.C. Most had never been on the water before.

Their guide, Trey Sherard of the Anacostia Riverkeeper, started the tour with a well-rehearsed safety talk. The nonprofit advocates for the protection of the river.

A boy with tousled black hair casually dipped his fingers in the water.

“Don’t touch it!” Sherard yelled.

Why was Sherard being so stern? Was it dangerously cold? Were there biting fish?

Because of the sewage.

“We get less sewage than we used to. Sewage is a code word for what?” Sherard asked the teenagers.

“Poop!” one student piped up.

“Human poop,” Sherard said. “Notice I didn’t say we get none. I said we get what? Less.”

Tours like this are designed to get young people interested in the river’s ecology, but it’s a fine line to tread — interacting with the water can make people sick. Because of the health risks, swimming hasn’t been legal in the Anacostia for more than half a century. The polluted water can cause gastrointestinal and respiratory illnesses, as well as eye, nose, and skin infections.

The river is the cleanest it’s been in years, according to environmental experts, but they still advise you not to take a dip in the Anacostia — not yet, at least.

About 40 million people in the U.S. live in a community with a combined sewer system, where wastewater and stormwater flow through the same pipes. When pipe capacities are reached after heavy rains, the overflow sends raw wastewater into the rivers instead of to a treatment plant.

Federal regulations, including sections of the Clean Water Act, require municipalities such as Washington to reduce at least 85% of this pollution or face steep fines.

To achieve compliance, Washington launched a $2.6 billion infrastructure project in 2011. DC Water’s Clean Rivers Project will eventually build multiple miles-long underground storage basins to capture stormwater and wastewater and pump it to treatment plants once heavy rains have subsided.

The Anacostia tunnel is the first of these storage basins to be completed. It can collect 190 million gallons of bacteria-laden wastewater for later treatment, said Moussa Wone, vice president of the Clean Rivers Project.

Climate change is causing more intense rainstorms in Washington, so even after construction is complete in 2030, Wone said, untreated stormwater will be discharged into the river, though much less frequently.

“On the Anacostia, we’re going to be reducing the frequency of overflows from 82 to two in an average year,” Wone said.

But while the Anacostia sewershed covers 176 square miles, he noted, only 17% is in Washington.

“The other 83% is outside the district,” Wone said. “We can do our part, but everybody else has to do their part also.”

Upstream in Maryland’s Montgomery and Prince George’s counties, miles of sewer lines are in the process of being upgraded to divert raw sewage to a treatment plant instead of the river.

The data shows that poop is a problem for river health — but knowing what kind of poop it is matters. Scientists monitor E. coli to indicate the presence of feces in river water, but since the bacteria live in the guts of most warm-blooded animals, the source is difficult to determine.

“Is it human feces? Or is it deer? Is it gulls’? Is it dogs’?” said Amy Sapkota, a professor of environmental and occupational health at the University of Maryland.

Bacterial levels can fluctuate across the river even without rainstorms. An Anacostia Riverkeeper report found that in 2023 just three of nine sites sampled along the Washington portion of the watershed had consistently low E. coli levels throughout the summer season.

Sapkota is heading a new bacterial monitoring program measuring the amount of E. coli that different animal species deposit along the river.

The team uses microbial source tracking to analyze samples of river water taken from different locations each month by volunteers. The molecular approach enables scientists to target specific gene sequences associated with fecal bacteria and determine whether the bacteria come from humans or wildlife. Microbial source tracking also measures fecal pollution levels by source.

“We can quantify the levels of different bacterial targets that may be coming from a human fecal source or an animal fecal source,” Sapkota said.

Her team expects to have preliminary results this year.

The health risk to humans from river water will never be zero, Sapkota said, but based on her team’s research, smart city planning and retooled infrastructure could lessen the level of harmful bacteria in the water.

“Let’s say that we’re finding that actually there’s a lot of deer fecal signatures in our results,” Sapkota said. “Maybe this points to the fact that we need more green buffers along the river that can help prevent fecal contaminants from wildlife from entering the river during stormwater events.”

Washington is hoping to recoup some of the cost of building green spaces and other river cleanup. In January, the office of D.C. Attorney General Brian Schwalb filed a lawsuit seeking unspecified damages from the federal government over decades of alleged pollution of the Anacostia River.

Brenda Lee Richardson, coordinator of the Anacostia Parks & Community Collaborative, said the efforts to cut down on trash and sewage are paying off. She sees a river on the mend, with more plant and animal life sprouting up.

“The ecosystem seems a lot greener,” she said. “There’s stuff in the river now that wasn’t there before.”

But any changes to the waterfront need to be done with residents of both sides of the river in mind, she said.

“We want there to be some sense of equity as it relates to who has access,” she said. “When I look at who is recreating, it’s not people who look like me.”

Richardson has lived for 40 years in Ward 8 — a predominantly Black area on the east side of the river whose residents are generally less affluent than those on the west side. She and her neighbors don’t consider the Anacostia a place to get out and play, she said.

As the water quality slowly improves, Richardson said, she hopes the Anacostia’s reputation is also rehabilitated. Even if it’s not safe to swim in, Richardson enjoys boating trips like the one with the Anacostia Riverkeeper.

“To see all those creatures along the way and the greenery. It was comforting,” she said. “So rather than take a pill to settle my nerves, I can just go down the river.”

KFF Health News is a national newsroom that produces in-depth journalism about health issues and is one of the core operating programs at KFF—an independent source of health policy research, polling, and journalism. Learn more about KFF.

Subscribe to KFF Health News’ free Morning Briefing.

This article first appeared on KFF Health News and is republished here under a Creative Commons license.

Don’t Forget…

Did you arrive here from our newsletter? Don’t forget to return to the email to continue learning!

Learn to Age Gracefully

Join the 98k+ American women taking control of their health & aging with our 100% free (and fun!) daily emails: