Who Screens The Sunscreens?

10almonds is reader-supported. We may, at no cost to you, receive a portion of sales if you purchase a product through a link in this article.

We Screen The Sunscreens!

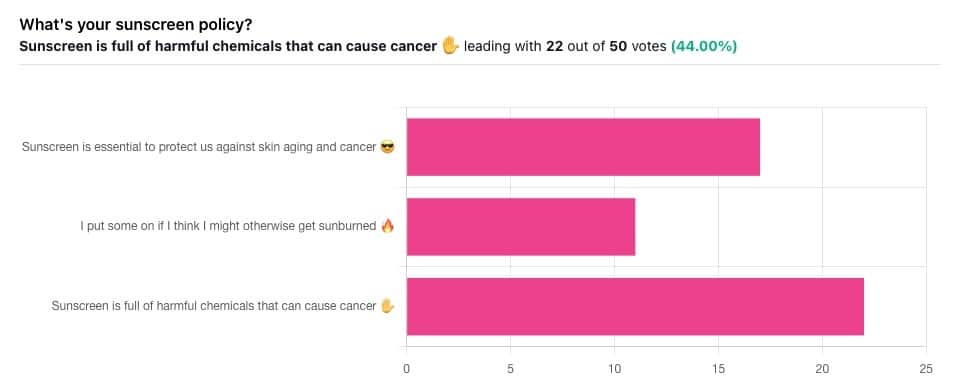

Yesterday, we asked you what your sunscreen policy was, and got a spread of answers. Apparently this one was quite polarizing!

One subscriber who voted for “Sunscreen is essential to protect us against skin aging and cancer” wrote:

❝My mom died of complications from melanoma, so we are vigilant about sun and sunscreen. We are a family of campers and hikers and gardeners—outdoors in all seasons—and we never burn❞

Our condolences with regard to your mom! Life is so precious, and when something like that happens, it tends to stick with us. We’re glad you and your family are taking care of yourselves.

Of the subscribers who voted for “I put some on if I think I might otherwise get sunburned”, about half wrote to express uncertainties:

- uncertainty about how safe it is, and

- uncertainty about how helpful it is

…so we’re going to tackle those questions in a moment. But what of those who voted for “Sunscreen is full of harmful chemicals that can cause cancer”?

Of those, only one wrote a message, which was to say one has to be very careful of what is in the formula.

Let’s take a look, then…

Sunscreen is full of harmful chemicals that can cause cancer: True or False?

False—according to current best science. Research is ongoing!

There are four main chemicals (found in most sunscreens) that people tend to worry about:

- Abobenzone

- Oxybenzone

- Octocrylene

- Ecamsule

Now, these two sound like four brands of rocket fuel, but then, dihydrogen monoxide (DHMO), which is also found in most sunscreens, sounds like a deadly toxin too. That’s water, by the way.

But what of these four chemicals? Well, as we say, research is ongoing, but we found a study that measured all four, to see how much got into the blood, and what adverse effects, if any, this caused.

We’ll skip to their conclusion:

❝In this preliminary study involving healthy volunteers, application of 4 commercially available sunscreens under maximal use conditions resulted in plasma concentrations that exceeded the threshold established by the FDA for potentially waiving some nonclinical toxicology studies for sunscreens. The systemic absorption of sunscreen ingredients supports the need for further studies to determine the clinical significance of these findings. These results do not indicate that individuals should refrain from the use of sunscreen.❞

Now, “exceeded the threshold established by the FDA for potentially waiving some nonclinical toxicology studies for sunscreens” sounds alarming, so why did they close with the words “These results do not indicate that individuals should refrain from the use of sunscreen”?

Let’s skip back up to a line from the results:

❝The most common adverse event was rash, which developed in 1 participant with each sunscreen.❞

This was most probably due to the oxybenzone, which can cause allergic skin reactions in some people.

Let us take a moment to remember the most common adverse event that occurs from not wearing sunscreen: sunburn!

You can read the full study here:

None of those ingredients have been found to be carcinogenic, even at the maximal blood plasma concentrations studied, from applications 4x/day to 75% of the body.

UVA rays, on the other hand, are absolutely very much known to cause cancer, and the effect is cumulative.

Sunscreen is essential to protect us against skin aging and cancer: True or False?

True, unequivocally, unless we live indoors and/or otherwise never go about under sunlight.

“But our ancestors—” lived under the same sun we do, and either used sunscreen or got advanced skin aging and cancer.

Sunscreen of times past ranged from mud to mineral lotions, but it’s pretty much always existed. Even non-human animals that have skin and don’t have fur or feathers, tend to take mud-baths in sunny parts of the world.

If you’d like to avoid oxybenzone and other chemicals, though, you might have your reasons. Maybe you’re allergic, or maybe you read that it’s a potential endocrine disruptor with estrogen-like and anti-androgenic properties that you don’t want.

There are other options, to include physical blockers containing zinc and titanium dioxide, which are generally recognized as safe and effective ingredients.

If you’re interested, you can even make your own sunscreen that blocks both UVA and UVB rays (UVA is what causes skin cancer; UVB is “milder” and is what causes sunburn):

Don’t Forget…

Did you arrive here from our newsletter? Don’t forget to return to the email to continue learning!

Recommended

Learn to Age Gracefully

Join the 98k+ American women taking control of their health & aging with our 100% free (and fun!) daily emails:

-

Older adults need another COVID-19 vaccine

10almonds is reader-supported. We may, at no cost to you, receive a portion of sales if you purchase a product through a link in this article.

What you need to know

- The CDC recommends people 65 and older and immunocompromised people receive an additional dose of the updated COVID-19 vaccine this spring—if at least four months have passed since they received a COVID-19 vaccine.

- Updated COVID-19 vaccines are effective at protecting against severe illness, hospitalization, death, and long COVID.

- The CDC also shortened the isolation period for people who are sick with COVID-19.

Last week, the CDC said people 65 and older should receive an additional dose of the updated COVID-19 vaccine this spring. The recommendation also applies to immunocompromised people, who were already eligible for an additional dose.

Older adults made up two-thirds of COVID-19-related hospitalizations between October 2023 and January 2024, so enhancing protection for this group is critical.

The CDC also shortened the isolation period for people who are sick with COVID-19, although the contagiousness of COVID-19 has not changed.

Read on to learn more about the CDC’s updated vaccination and isolation recommendations.

Who is eligible for another COVID-19 vaccine this spring?

The CDC recommends that people ages 65 and older and immunocompromised people receive an additional dose of the updated COVID-19 vaccine this spring—if at least four months have passed since they received a COVID-19 vaccine. It’s safe to receive an updated COVID-19 vaccine from Pfizer, Moderna, or Novavax, regardless of which COVID-19 vaccines you received in the past.

Updated COVID-19 vaccines are available at pharmacies, local clinics, or doctor’s offices. Visit Vaccines.gov to find an appointment near you.

Under- and uninsured adults can get the updated COVID-19 vaccine for free through the CDC’s Bridge Access Program. If you’re over 60 and unable to leave your home, call the Aging Network at 1-800-677-1116 to learn about free at-home vaccination options.

What are the benefits of staying up to date on COVID-19 vaccines?

Staying up to date on COVID-19 vaccines prevents severe illness, hospitalization, death, and long COVID.

Additionally, the CDC says staying up to date on COVID-19 vaccines is a safer and more reliable way to build protection against COVID-19 than getting sick from COVID-19.

What are the new COVID-19 isolation guidelines?

According to the CDC’s general respiratory virus guidance, people who are sick with COVID-19 or another common respiratory illness, like the flu or RSV, should isolate until they’ve been fever-free for at least 24 hours without the use of fever-reducing medication and their symptoms improve.

After that, the CDC recommends taking additional precautions for the next five days: wearing a well-fitting mask, limiting close contact with others, and improving ventilation in your home if you live with others.

If you’re sick with COVID-19, you can infect others for five to 12 days, or longer. Moderately or severely immunocompromised patients may remain infectious beyond 20 days.

For more information, talk to your health care provider.

This article first appeared on Public Good News and is republished here under a Creative Commons license.

Share This Post

-

Needle Pain Is a Big Problem for Kids. One California Doctor Has a Plan.

10almonds is reader-supported. We may, at no cost to you, receive a portion of sales if you purchase a product through a link in this article.

Almost all new parents go through it: the distress of hearing their child scream at the doctor’s office. They endure the emotional torture of having to hold their child down as the clinician sticks them with one vaccine after another.

“The first shots he got, I probably cried more than he did,” said Remy Anthes, who was pushing her 6-month-old son, Dorian, back and forth in his stroller in Oakland, California.

“The look in her eyes, it’s hard to take,” said Jill Lovitt, recalling how her infant daughter Jenna reacted to some recent vaccines. “Like, ‘What are you letting them do to me? Why?’”

Some children remember the needle pain and quickly start to internalize the fear. That’s the fear Julia Cramer witnessed when her 3-year-old daughter, Maya, had to get blood drawn for an allergy test at age 2.

“After that, she had a fear of blue gloves,” Cramer said. “I went to the grocery store and she saw someone wearing blue gloves, stocking the vegetables, and she started freaking out and crying.”

Pain management research suggests that needle pokes may be children’s biggest source of pain in the health care system. The problem isn’t confined to childhood vaccinations either. Studies looking at sources of pediatric pain have included children who are being treated for serious illness, have undergone heart surgeries or bone marrow transplants, or have landed in the emergency room.

“This is so bad that many children and many parents decide not to continue the treatment,” said Stefan Friedrichsdorf, a specialist at the University of California-San Francisco’s Stad Center for Pediatric Pain, speaking at the End Well conference in Los Angeles in November.

The distress of needle pain can follow children as they grow and interfere with important preventive care. It is estimated that a quarter of all adults have a fear of needles that began in childhood. Sixteen percent of adults refuse flu vaccinations because of a fear of needles.

Friedrichsdorf said it doesn’t have to be this bad. “This is not rocket science,” he said.

He outlined simple steps that clinicians and parents can follow:

- Apply an over-the-counter lidocaine, which is a numbing cream, 30 minutes before a shot.

- Breastfeed babies, or give them a pacifier dipped in sugar water, to comfort them while they’re getting a shot.

- Use distractions like teddy bears, pinwheels, or bubbles to divert attention away from the needle.

- Don’t pin kids down on an exam table. Parents should hold children in their laps instead.

At Children’s Minnesota, Friedrichsdorf practiced the “Children’s Comfort Promise.” Now he and other health care providers are rolling out these new protocols for children at UCSF Benioff Children’s Hospitals in San Francisco and Oakland. He’s calling it the “Ouchless Jab Challenge.”

If a child at UCSF needs to get poked for a blood draw, a vaccine, or an IV treatment, Friedrichsdorf promises, the clinicians will do everything possible to follow these pain management steps.

“Every child, every time,” he said.

It seems unlikely that the ouchless effort will make a dent in vaccine hesitancy and refusal driven by the anti-vaccine movement, since the beliefs that drive it are often rooted in conspiracies and deeply held. But that isn’t necessarily Friedrichsdorf’s goal. He hopes that making routine health care less painful can help sway parents who may be hesitant to get their children vaccinated because of how hard it is to see them in pain. In turn, children who grow into adults without a fear of needles might be more likely to get preventive care, including their yearly flu shot.

In general, the onus will likely be on parents to take a leading role in demanding these measures at medical centers, Friedrichsdorf said, because the tolerance and acceptance of children’s pain is so entrenched among clinicians.

Diane Meier, a palliative care specialist at Mount Sinai, agrees. She said this tolerance is a major problem, stemming from how doctors are usually trained.

“We are taught to see pain as an unfortunate, but inevitable side effect of good treatment,” Meier said. “We learn to repress that feeling of distress at the pain we are causing because otherwise we can’t do our jobs.”

During her medical training, Meier had to hold children down for procedures, which she described as torture for them and for her. It drove her out of pediatrics. She went into geriatrics instead and later helped lead the modern movement to promote palliative care in medicine, which became an accredited specialty in the United States only in 2006.

Meier said she thinks the campaign to reduce needle pain and anxiety should be applied to everyone, not just to children.

“People with dementia have no idea why human beings are approaching them to stick needles in them,” she said. And the experience can be painful and distressing.

Friedrichsdorf’s techniques would likely work with dementia patients, too, she said. Numbing cream, distraction, something sweet in the mouth, and perhaps music from the patient’s youth that they remember and can sing along to.

“It’s worthy of study and it’s worthy of serious attention,” Meier said.

This article is from a partnership that includes KQED, NPR, and KFF Health News.

KFF Health News is a national newsroom that produces in-depth journalism about health issues and is one of the core operating programs at KFF—an independent source of health policy research, polling, and journalism. Learn more about KFF.

USE OUR CONTENT

This story can be republished for free (details).

KFF Health News is a national newsroom that produces in-depth journalism about health issues and is one of the core operating programs at KFF—an independent source of health policy research, polling, and journalism. Learn more about KFF.

Subscribe to KFF Health News’ free Morning Briefing.

Share This Post

-

Her Mental Health Treatment Was Helping. That’s Why Insurance Cut Off Her Coverage.

10almonds is reader-supported. We may, at no cost to you, receive a portion of sales if you purchase a product through a link in this article.

Reporting Highlights

- Progress Denials: Insurers use a patient’s improvement to justify denying mental health coverage.

- Providers Disagree: Therapists argue with insurers and the doctors they employ to continue covering treatment for their patients.

- Patient Harm: Some patients backslid when insurers cut off coverage for treatment at key moments.

These highlights were written by the reporters and editors who worked on this story.

Geneva Moore’s therapist pulled out her spiral notebook. At the top of the page, she jotted down the date, Jan. 30, 2024, Moore’s initials and the name of the doctor from the insurance company to whom she’d be making her case.

She had only one chance to persuade him, and by extension Blue Cross and Blue Shield of Texas, to continue covering intensive outpatient care for Moore, a patient she had come to know well over the past few months.

The therapist, who spoke on the condition of anonymity out of fear of retaliation from insurers, spent the next three hours cramming, as if she were studying for a big exam. She combed through Moore’s weekly suicide and depression assessments, group therapy notes and write-ups from their past few sessions together.

She filled two pages with her notes: Moore had suicidal thoughts almost every day and a plan for how she would take her own life. Even though she expressed a desire to stop cutting her wrists, she still did as often as three times a week to feel the release of pain. She only had a small group of family and friends to offer support. And she was just beginning to deal with her grief and trauma over sexual and emotional abuse, but she had no healthy coping skills.

Less than two weeks earlier, the therapist’s supervisor had struck out with another BCBS doctor. During that call, the insurance company psychiatrist concluded Moore had shown enough improvement that she no longer needed intensive treatment. “You have made progress,” the denial letter from BCBS Texas read.

When the therapist finally got on the phone with a second insurance company doctor, she spoke as fast as she could to get across as many of her points as possible.

“The biggest concern was the abnormal thoughts — the suicidal ideation, self-harm urges — and extensive trauma history,” the therapist recalled in an interview with ProPublica. “I was really trying to emphasize that those urges were present, and they were consistent.”

She told the company doctor that if Moore could continue on her treatment plan, she would likely be able to leave the program in 10 weeks. If not, her recovery could be derailed.

The doctor wasn’t convinced. He told the therapist that he would be upholding the initial denial. Internal notes from the BCBS Texas doctors say that Moore exhibited “an absence of suicidal thoughts,” her symptoms had “stabilized” and she could “participate in a lower level of care.”

The call lasted just seven minutes.

Moore was sitting in her car during her lunch break when her therapist called to give her the news. She was shocked and had to pull herself together to resume her shift as a technician at a veterinary clinic.

“The fact that it was effective immediately,” Moore said later, “I think that was the hardest blow of it all.”

Many Americans must rely on insurers when they or family members are in need of higher-touch mental health treatment, such as intensive outpatient programs or round-the-clock care in a residential facility. The costs are high, and the stakes for patients often are, too. In 2019 alone, the U.S. spent more than $106.5 billion treating adults with mental illness, of which private insurance paid about a third. One 2024 study found that the average quoted cost for a month at a residential addiction treatment facility for adolescents was more than $26,000.

Health insurers frequently review patients’ progress to see if they can be moved down to a lower — and almost always cheaper — level of care. That can cut both ways. They sometimes cite a lack of progress as a reason to deny coverage, labeling patients’ conditions as chronic and asserting that they have reached their baseline level of functioning. And if they make progress, which would normally be celebrated, insurers have used that against patients to argue they no longer need the care being provided.

Their doctors are left to walk a tightrope trying to convince insurers that patients are making enough progress to stay in treatment as long as they actually need it, but not so much that the companies prematurely cut them off from care. And when insurers demand that providers spend their time justifying care, it takes them away from their patients.

“The issues that we grapple with are in the real world,” said Dr. Robert Trestman, the chair of psychiatry and behavioral medicine at the Virginia Tech Carilion School of Medicine and chair of the American Psychiatric Association’s Council on Healthcare Systems and Financing. “People are sicker with more complex conditions.”

Mental health care can be particularly prone to these progress-based denials. While certain tests reveal when cancer cells are no longer present and X-rays show when bones have healed, psychiatrists say they have to determine whether someone has returned to a certain level of functioning before they can end or change their treatment. That can be particularly tricky when dealing with mental illness, which can be fluid, with a patient improving slightly one day only to worsen the next.

Though there is no way to know how often coverage gets cut off mid-treatment, ProPublica has found scores of lawsuits over the past decade in which judges have sharply criticized insurance companies for citing a patient’s improvement to deny mental health coverage. In a number of those cases, federal courts ruled that the insurance companies had broken a federal law designed to provide protections for people who get health insurance through their jobs.

Reporters reviewed thousands of pages of court documents and interviewed more than 50 insiders, lawyers, patients and providers. Over and over, people said these denials can lead to real — sometimes devastating — harm. An official at an Illinois facility with intensive mental health programs said that this past year, two patients who left before their clinicians felt they were ready due to insurance denials had attempted suicide.

Dr. Eric Plakun, a Massachusetts psychiatrist with more than 40 years of experience in residential and intensive outpatient programs, and a former board member of the American Psychiatric Association, said the “proprietary standards” insurers use as a basis for denying coverage often simply stabilize patients in crisis and “shortcut real treatment.”

Plakun offered an analogy: If someone’s house is on fire, he said, putting out the fire doesn’t restore the house. “I got a hole in the roof, and the windows have been smashed in, and all the furniture is charred, and nothing’s working electrically,” he said. “How do we achieve recovery? How do we get back to living in that home?”

Unable to pay the $350-a-day out-of-pocket cost for additional intensive outpatient treatment, Moore left her program within a week of BCBS Texas’ denial. The insurer would only cover outpatient talk therapy.

During her final day at the program, records show, Moore’s suicidal thoughts and intent to carry them out had escalated from a 7 to a 10 on a 1-to-10 scale. She was barely eating or sleeping.

A few hours after the session, Moore drove herself to a hospital and was admitted to the emergency room, accelerating a downward spiral that would eventually cost the insurer tens of thousands of dollars, more than the cost of the treatment she initially requested.

How Insurers Justify Denials

Buried in the denial letters that insurance companies send patients are a variety of expressions that convey the same idea: Improvement is a reason to deny coverage.

“You are better.” “Your child has made progress.” “You have improved.”

In one instance, a doctor working for Regence Blue Cross and Blue Shield of Oregon wrote that a patient who had been diagnosed with major depression was “sufficiently stable,” even as her own doctors wrote that she “continued to display a pattern of severe impairment” and needed round-the-clock care. A judge ruled that “a preponderance of the evidence” demonstrated that the teen’s continued residential treatment was medically necessary. The insurer said it can’t comment on the case because it ended with a confidential settlement.

In another, a doctor working for UnitedHealth Group wrote in 2019 that a teenage girl with a history of major depression who had been hospitalized after trying to take her own life by overdosing “was doing better.” The insurer denied ongoing coverage at a residential treatment facility. A judge ruled that the insurer’s determination “lacked any reasoning or citations” from the girl’s medical records and found that the insurer violated federal law. United did not comment on this case but previously argued that the girl no longer had “concerning medical issues” and didn’t need treatment in a 24-hour monitored setting.

To justify denials, the insurers cite guidelines that they use to determine how well a patient is doing and, ultimately, whether to continue paying for care. Companies, including United, have said these guidelines are independent, widely accepted and evidence-based.

Insurers most often turn to two sets: MCG (formerly known as Milliman Care Guidelines), developed by a division of the multibillion-dollar media and information company Hearst, and InterQual, produced by a unit of UnitedHealth’s mental health division, Optum. Insurers have also used guidelines they have developed themselves.

MCG Health did not respond to multiple requests for comment. A spokesperson for the Optum division that works on the InterQual guidelines said that the criteria “is a collection of established scientific evidence and medical practice intended for use as a first level screening tool” and “helps to move patients safely and efficiently through the continuum of care.”

A separate spokesperson for Optum also said the company’s “priority is ensuring the people we serve receive safe and effective care for their individual needs.” A Regence spokesperson said that the company does “not make coverage decisions based on cost or length of stay,” and that its “number one priority is to ensure our members have access to the care they need when they need it.”

In interviews, several current and former insurance employees from multiple companies said that they were required to prioritize the proprietary guidelines their company used, even if their own clinical judgment pointed in the opposite direction.

“It’s very hard when you come up against all these rules that are kind of setting you up to fail the patient,” said Brittainy Lindsey, a licensed mental health counselor who worked at the Anthem subsidiary Beacon and at Humana for a total of six years before leaving the industry in 2022. In her role, Lindsey said, she would suggest approving or denying coverage, which — for the latter — required a staff doctor’s sign-off. She is now a mental health consultant for behavioral health businesses and clinicians.

A spokesperson for Elevance Health, formerly known as Anthem, said Lindsey’s “recollection is inaccurate, both in terms of the processes that were in place when she was a Beacon employee, and how we operate today.” The spokesperson said “clinical judgment by a physician — which Ms. Lindsey was not — always takes precedence over guidelines.”

In an emailed statement, a Humana spokesperson said the company’s clinician reviewers “are essential to evaluating the facts and circumstances of each case.” But, the spokesperson said, “having objective criteria is also important to provide checks and balances and consistently comply with” federal requirements.

The guidelines are a pillar of the health insurance system known as utilization management, which paves the way for coverage denials. The process involves reviewing patients’ cases against relevant criteria every handful of days or so to assess if the company will continue paying for treatment, requiring providers and patients to repeatedly defend the need for ongoing care.

Federal judges have criticized insurance company doctors for using such guidelines in cases where they were not actually relevant to the treatment being requested or for “solely” basing their decisions on them.

Wit v. United Behavioral Health, a class-action lawsuit involving a subsidiary of UnitedHealth, has become one of the most consequential mental health cases of this century. In that case, a federal judge in California concluded that a number of United’s in-house guidelines did not adhere to generally accepted standards of care. The judge found that the guidelines allowed the company to wrongly deny coverage for certain mental health and substance use services the moment patients’ immediate problems improved. He ruled that the insurer would need to change its practices. United appealed the ruling on grounds other than the court’s findings about the defects in its guidelines, and a panel of judges partially upheld the decision. The case has been sent back to the district court for further proceedings.

Largely in response to the Wit case, nine states have passed laws requiring health insurers to use guidelines that align with the leading standards of mental health care, like those developed by nonprofit professional organizations.

Cigna has said that it “has chosen not to adopt private, proprietary medical necessity criteria” like MCG. But, according to a review of lawsuits, denial letters have continued to reference MCG. One federal judge in Utah called out the company, writing that Cigna doctors “reviewed the claims under medical necessity guidelines it had disavowed.” Cigna did not respond to specific questions about this.

Timothy Stock, one of the BCBS doctors who denied Moore’s request to cover ongoing care, had cited MCG guidelines when determining she had improved enough — something judges noted he had done before. In 2016, Stock upheld a decision on appeal to deny continued coverage for a teenage girl who was in residential treatment for major depression, post-traumatic stress disorder and anxiety. Pointing to the guidelines, Stock concluded she had shown enough improvement.

The patient’s family sued the insurer, alleging it had wrongly denied coverage. Blue Cross and Blue Shield of Illinois argued that there was evidence that showed the patient had been improving. But, a federal judge found the insurer misstated its significance. The judge partially ruled in the family’s favor, zeroing in on Stock and another BCBS doctor’s use of improvement to recommend denying additional care.

“The mere incidence of some improvement does not mean treatment was no longer medically necessary,” the Illinois judge wrote.

In another case, BCBS Illinois denied coverage for a girl with a long history of mental illness just a few weeks into her stay at a residential treatment facility, noting that she was “making progressive improvements.” Stock upheld the denial after an appeal.

Less than two weeks after Stock’s decision, court records show, she cut herself on the arm and leg with a broken light bulb. The insurer defended the company’s reasoning by noting that the girl “consistently denied suicidal ideation,” but a judge wrote that medical records show the girl was “not forthcoming” with her doctors about her behaviors. The judge ruled against the insurer, writing that Stock and another BCBS doctor “unreasonably ignored the weight of the medical evidence” showing that the girl required residential treatment.

Stock declined to comment. A spokesperson for BCBS said the company’s doctors who review requests for mental health coverage are board certified psychiatrists with multiple years of practice experience. The spokesperson added that the psychiatrists review all information received “from the provider, program and members to ensure members are receiving benefits for the right care, at the right place and at the right time.”

The BCBS spokesperson did not address specific questions related to Moore or Stock. The spokesperson said that the examples ProPublica asked about “are not indicative of the experience of the vast majority of our members,” and that it is committed to providing “access to quality, cost-effective physical and behavioral health care.”

A Lifelong Struggle

A former contemporary dancer with a bright smile and infectious laugh, Moore’s love of animals is eclipsed only by her affinity for plants. She moved from Indiana to Austin, Texas, about six years ago and started as a receptionist at a clinic before working her way up to technician.

Moore’s depression has been a constant in her life. It began as a child, when, she said, she was sexually and emotionally abused. She was able to manage as she grew up, getting through high school and attending Indiana University. But, she said, she fell back into a deep sadness after she learned in 2022 that the church she found comfort in as a college student turned out to be what she and others deemed a cult. In September of last year, she began an intensive outpatient program, which included multiple group and individual therapy sessions every week.

Moore, 32, had spent much of the past eight months in treatment for severe depression, post-traumatic stress disorder and anxiety when BCBS said it would no longer pay for the program in January.

The denial had come to her without warning.

“I was starting to get to the point where I did have some hope, and I was like, maybe I can see an actual end to this,” Moore said. “And it was just cut off prematurely.”

At the Austin emergency room where she drove herself after her treatment stopped, her heart raced. She was given medication as a sedative for her anxiety. According to hospital records she provided to ProPublica, Moore’s symptoms were brought on after “insurance said they would no longer pay.”

A hospital social worker frantically tried to get her back into the intensive outpatient program.

“That’s the sad thing,” said Kandyce Walker, the program’s director of nursing and chief operating officer, who initially argued Moore’s case with BCBS Texas. “To have her go from doing a little bit better to ‘I’m going to kill myself.’ It is so frustrating, and it’s heartbreaking.”

After the denial and her brief admission to the hospital emergency department in January, Moore began slicing her wrists more frequently, sometimes twice a day. She began to down six to seven glasses of wine a night.

“I really had thought and hoped that with the amount of work I’d put in, that I at least would have had some fumes to run on,” she said.

She felt embarrassed when she realized she had nothing to show for months of treatment. The skills she’d just begun to practice seemed to disappear under the weight of her despair. She considered going into debt to cover the cost of ongoing treatment but began to think that she’d rather end her life.

“In my mind,” she said, “that was the most practical thing to do.”

Whenever the thought crossed her mind — and it usually did multiple times a day — she remembered that she had promised her therapist that she wouldn’t.

Moore’s therapist encouraged her to continue calling BCBS Texas to try to restore coverage for more intensive treatment. In late February, about five weeks after Stock’s denial, records show that the company approved a request that sent her back to the same facility and at the same level of care as before.

But by that time, her condition had deteriorated so severely that it wasn’t enough.

Eight days later, Moore was admitted to a psychiatric hospital about half an hour from Austin. Medical records paint a harrowing picture of her condition. She had a plan to overdose and the medicine to do it. The doctor wrote that she required monitoring and had “substantial ongoing suicidality.” The denial continued to torment her. She told her doctor that her condition worsened after “insurance stopped covering” her treatment.

Her few weeks stay at the psychiatric hospital cost $38,945.06. The remaining 10 weeks of treatment at the intensive outpatient program — the treatment BCBS denied — would have cost about $10,000.

Moore was discharged from the hospital in March and went back into the program Stock had initially said she no longer needed.

It marked the third time she was admitted to the intensive outpatient program.

A few months later, as Moore picked at her lunch, her oversized glasses sliding down the bridge of her nose every so often, she wrestled with another painful realization. Had the BCBS doctors not issued the denial, she probably would have completed her treatment by now.

“I was really looking forward to that,” Moore said softly. As she spoke, she played with the thick stack of bracelets hiding the scars on her wrists.

A few weeks later, that small facility closed in part because of delays and denials from insurance companies, according to staff and billing records. Moore found herself calling around to treatment facilities to see which ones would accept her insurance. She finally found one, but in October, her depression had become so severe that she needed to be stepped up to a higher level of care.

Moore was able to get a leave of absence from work to attend treatment, which she worried would affect the promotion she had been working toward. To tide her over until she could go back to work, she used up the money her mother sent for her 30th birthday.

She smiles less than she did even a few months ago. When her roommates ask her to hang out downstairs, she usually declines. She has taken some steps forward, though. She stopped drinking and cutting her wrists, allowing scar tissue to cover her wounds.

But she’s still grieving what the denial took from her.

“I believed I could get better,” she said recently, her voice shaking. “With just a little more time, I could discharge, and I could live life finally.”

Kirsten Berg contributed research.

Share This Post

Related Posts

-

The Power of Self-Care – by Dr. Sunil Kumar

10almonds is reader-supported. We may, at no cost to you, receive a portion of sales if you purchase a product through a link in this article.

First, what this book is mostly not about: bubble baths and scented candles. We say “mostly”, because stress management is an important aspect given worthy treatment in this book, but there is more emphasis on evidence-based interventions and thus Dr. Kumar is readier to prescribe nature walks and meditation, than product-based pampering sessions.

As is made clear in the subtitle “Transforming Heart Health with Lifestyle Medicine”, the focus is on heart health throughout, but as 10almonds readers know, “what’s good for your heart is good for your brain” is a truism that indeed holds true here too.

Dr. Kumar also gives nutritional tweaks to optimize heart health, and includes a selection of heart-healthy recipes, too. And exercise? Yes, customizable exercise plans, even. And a plan for getting sleep into order if perchance it has got a bit out of hand (most people get less sleep than necessary for maintenance of good health), and he even delves into “social prescribing”, that is to say, making sure that one’s social connectedness does not get neglected—without letting it, conversely, take over too much of one’s life (done badly, social connectedness can be a big source of unmanaged stress).

Perhaps the most value of this book comes from its 10-week self-care plan (again, with a focus on heart health), basically taking the reader by the hand for long enough that, after those 10 weeks, habits should be quite well-ingrained.

A strong idea throughout is that the things we take up should be sustainable, because well, a heart is for life, not just for a weekend retreat.

Bottom line: if you’d like to improve your heart health in a way that feels like self-care rather than an undue amount of work, then this is the book for you.

Don’t Forget…

Did you arrive here from our newsletter? Don’t forget to return to the email to continue learning!

Learn to Age Gracefully

Join the 98k+ American women taking control of their health & aging with our 100% free (and fun!) daily emails:

-

9 Reasons To Avoid Mobility Training

10almonds is reader-supported. We may, at no cost to you, receive a portion of sales if you purchase a product through a link in this article.

Why might someone not want to do mobility training? Here are some important reasons:

Make an informed choice

Here’s Liv’s hit-list of reasons to skip mobility training:

- Poor Circulation: Avoid mobility training if you don’t want to improve or maintain good blood circulation, which aids muscle recovery and reduces soreness.

- Low Energy Levels: Mobility training increases oxygen flow to the brain and muscles, boosting energy. Skip it if you prefer feeling sluggish!

- Digestive Health: Stretches that rotate the torso aid digestion and relieve bloating. Definitely best to avoid it if you’re uninterested in improving digestive health.

- Joint Health: Mobility work stimulates synovial fluid production, reducing joint friction and promoting longevity. You can skip it if you don’t care about comfortable movement.

- Sleep Quality: Gentle stretching triggers relaxation, aiding restful sleep. Avoid it if you enjoy restless nights!

- Pain Tolerance: Stretching trains the nervous system to handle discomfort better. Skip it if you prefer suffering 🙂

- Headache Reduction: Mobility work relieves tension in the neck and shoulders, reducing the occurrence and severity of headaches. No need to do it if you’re fine with frequent headaches.

- Immune System Support: Mobility training boosts lymphatic circulation, aiding the immune system. Avoid it if you prefer your immune system to get exciting in a bad way.

- Stress Reduction: Mobility exercises release endorphins and lower cortisol levels, reducing stress. So, it is certainly best to skip it if you prefer feeling stressed and enjoy the many harmful symptoms of high cortisol levels!

For more on all of these, enjoy:

Click Here If The Embedded Video Doesn’t Load Automatically!

Want to learn more?

You might also like to read:

Mobility As Though A Sporting Pursuit: Train For The Event Of Your Life!

Take care!

Don’t Forget…

Did you arrive here from our newsletter? Don’t forget to return to the email to continue learning!

Learn to Age Gracefully

Join the 98k+ American women taking control of their health & aging with our 100% free (and fun!) daily emails:

-

What Actually Causes High Cholesterol?

10almonds is reader-supported. We may, at no cost to you, receive a portion of sales if you purchase a product through a link in this article.

In 1968, the American Heart Association advised limiting egg consumption to three per week due to cholesterol concerns linked to cardiovascular disease. Which was reasonable based on the evidence available back then, but it didn’t stand the test of time.

Eggs are indeed high in cholesterol, but that doesn’t mean that those who eat them will also be high in cholesterol, because…

It’s not quite what many people think

Some quite dietary pointers to start with:

- Egg yolks are high in cholesterol but have a minimal impact on blood cholesterol.

- Saturated and trans fats (as found in fatty meats or dairy, and some processed foods) have a greater influence on LDL levels than dietary cholesterol.

And on the other hand:

- Unsaturated fats (e.g. from fish, nuts, seeds) have anti-inflammatory benefits

- Fiber-rich foods help lower LDL by affecting fat absorption in the digestive tract

A quick primer on LDL and other kinds of cholesterol:

- VLDL (Very Low-Density Lipoprotein):

- delivers triglycerides and cholesterol to muscle and fat cells for energy

- is converted into LDL after delivery

- LDL (Low-Density Lipoprotein):

- is called “bad cholesterol”, which we call that due to its role in arterial plaque formation

- in excess leads to inflammation, overworked macrophage activity, and artery narrowing

- HDL (High-Density Lipoprotein):

- known as “good cholesterol,” picks up excess LDL and returns it to the liver for excretion

- is anti-inflammatory, in addition to regulating LDL levels

There are other factors too, for example:

- Smoking and drinking increase LDL buildup and cause oxidative damage to lipids in general and the blood vessels through which they travel

- Regular exercise, meanwhile, can lower LDL and raise HDL

- Statins and other medications can help lower LDL and manage cholesterol when lifestyle changes and genetics require additional support—but they often come with serious side effects, and the usefulness varies from person to person.

For more on all of this, enjoy:

Click Here If The Embedded Video Doesn’t Load Automatically!

Want to learn more?

You might also like to read:

Take care!

Don’t Forget…

Did you arrive here from our newsletter? Don’t forget to return to the email to continue learning!

Learn to Age Gracefully

Join the 98k+ American women taking control of their health & aging with our 100% free (and fun!) daily emails: