Why do disinfectants only kill 99.9% of germs? Here’s the science

10almonds is reader-supported. We may, at no cost to you, receive a portion of sales if you purchase a product through a link in this article.

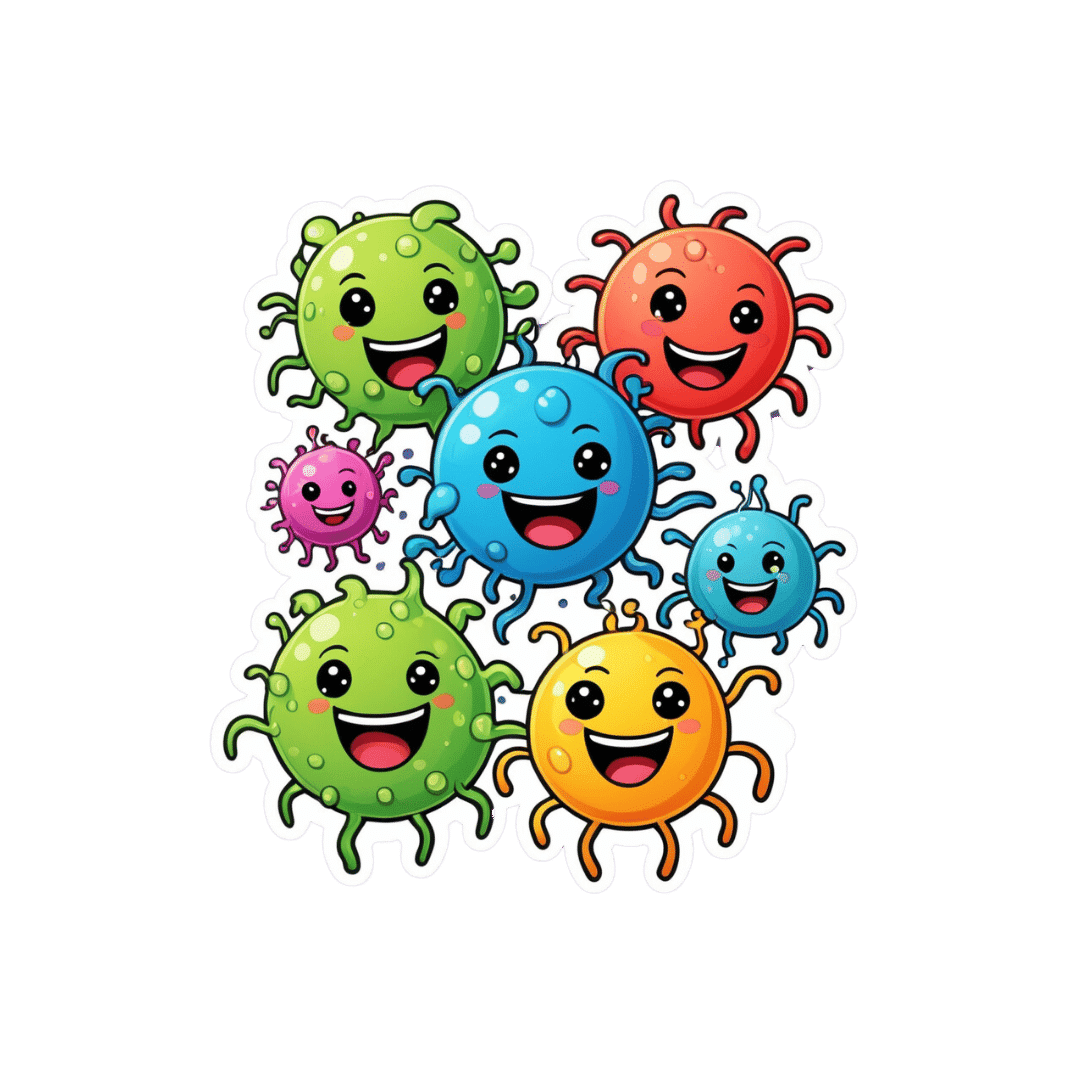

Have you ever wondered why most disinfectants indicate they kill 99.9% or 99.99% of germs, but never promise to wipe out all of them? Perhaps the thought has crossed your mind mid-way through cleaning your kitchen or bathroom.

Surely, in a world where science is able to do all sorts of amazing things, someone would have invented a disinfectant that is 100% effective?

The answer to this conundrum requires understanding a bit of microbiology and a bit of mathematics.

What is a disinfectant?

A disinfectant is a substance used to kill or inactivate bacteria, viruses and other microbes on inanimate objects.

There are literally millions of microbes on surfaces and objects in our domestic environment. While most microbes are not harmful (and some are even good for us) a small proportion can make us sick.

Although disinfection can include physical interventions such as heat treatment or the use of UV light, typically when we think of disinfectants we are referring to the use of chemicals to kill microbes on surfaces or objects.

Chemical disinfectants often contain active ingredients such as alcohols, chlorine compounds and hydrogen peroxide which can target vital components of different microbes to kill them.

The maths of microbial elimination

In the past few years we’ve all become familiar with the concept of exponential growth in the context of the spread of COVID cases.

This is where numbers grow at an ever-accelerating rate, which can lead to an explosion in the size of something very quickly. For example, if a colony of 100 bacteria doubles every hour, in 24 hours’ time the population of bacteria would be more than 1.5 billion.

Conversely, the killing or inactivating of microbes follows a logarithmic decay pattern, which is essentially the opposite of exponential growth. Here, while the number of microbes decreases over time, the rate of death becomes slower as the number of microbes becomes smaller.

For example, if a particular disinfectant kills 90% of bacteria every minute, after one minute, only 10% of the original bacteria will remain. After the next minute, 10% of that remaining 10% (or 1% of the original amount) will remain, and so on.

Because of this logarithmic decay pattern, it’s not possible to ever claim you can kill 100% of any microbial population. You can only ever scientifically say that you are able to reduce the microbial load by a proportion of the initial population. This is why most disinfectants sold for domestic use indicate they kill 99.9% of germs.

Other products such as hand sanitisers and disinfectant wipes, which also often purport to kill 99.9% of germs, follow the same principle.

Real-world implications

As with a lot of science, things get a bit more complicated in the real world than they are in the laboratory. There are a number of other factors to consider when assessing how well a disinfectant is likely to remove microbes from a surface.

One of these factors is the size of the initial microbial population that you’re trying to get rid of. That is, the more contaminated a surface is, the harder the disinfectant needs to work to eliminate the microbes.

If for example you were to start off with only 100 microbes on a surface or object, and you removed 99.9% of these using a disinfectant, you could have a lot of confidence that you have effectively removed all the microbes from that surface or object (called sterilisation).

In contrast, if you have a large initial microbial population of hundreds of millions or billions of microbes contaminating a surface, even reducing the microbial load by 99.9% may still mean there are potentially millions of microbes remaining on the surface.

Time is is a key factor that determines how effectively microbes are killed. So exposing a highly contaminated surface to disinfectant for a longer period is one way to ensure you kill more of the microbial population.

This is why if you look closely at the labels of many common household disinfectants, they will often suggest that to disinfect you should apply the product then wait a specified time before wiping clean. So always consult the label on the product you’re using.

Other factors such as temperature, humidity and the type of surface also influence how well a disinfectant works outside the lab.

Similarly, microbes in the real world may be either more or less sensitive to disinfection than those used for testing in the lab.

Disinfectants are one part infection control

The sensible use of disinfectants plays an important role in our daily lives in reducing our exposure to pathogens (microbes that cause illness). They can therefore reduce our chances of getting sick.

The fact disinfectants can’t be shown to be 100% effective from a scientific perspective in no way detracts from their importance in infection control. But their use should always be complemented by other infection control practices, such as hand washing, to reduce the risk of infection.

Hassan Vally, Associate Professor, Epidemiology, Deakin University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Don’t Forget…

Did you arrive here from our newsletter? Don’t forget to return to the email to continue learning!

Recommended

Learn to Age Gracefully

Join the 98k+ American women taking control of their health & aging with our 100% free (and fun!) daily emails:

-

4 Tips To Stand Without Using Hands

10almonds is reader-supported. We may, at no cost to you, receive a portion of sales if you purchase a product through a link in this article.

The “sit-stand” test, getting up off the floor without using one’s hands, is well-recognized as a good indicator of healthy aging, and predictor of longevity. But what if you can’t do it? Rather than struggling, there are exercises to strengthen the body to be able to do this vital movement.

Step by step

Teresa Shupe has been teaching Pilates professionally full-time for over 25 years, and here’s what she has to offer in the category of safe and effective ways of improving balance and posture while doing the sitting-to-standing movement:

- Squat! Doing squats (especially deep ones) regularly strengthens all the parts necessary to effectively complete this movement. If your knees aren’t up to it at first, do the squats with your back against a wall to start with.

- Roll! On your back, cross your feet as though preparing to stand, and rock-and-roll your body forwards. To start with you can “cheat” and use your fingertips to give a slight extra lift. This exercise builds mobility in the various necessary parts of the body, and also strengthens the core—as well as getting you accustomed to using your bodyweight to move your body forwards.

- Lift! This one’s focusing on that last part, and taking it further. Because it may be difficult to get enough momentum initially, you can practice by holding small weights in your hands, to shift your centre of gravity forwards a bit. Unlike many weights exercises, in this case you’re going to transition to holding less weight rather than more, though.

- Complete! Continue from the above, without weights now; use the blades of your feet to stand. If you need to, use your fingertips to give you a touch more lift and stability, and reduce the fingers that you use until you are using none.

For more on each of these as well as a visual demonstration, enjoy this short video:

Click Here If The Embedded Video Doesn’t Load Automatically!

Further reading

For more exercises with a similar approach, check out:

Mobility As A Sporting Pursuit

Take care!

Share This Post

-

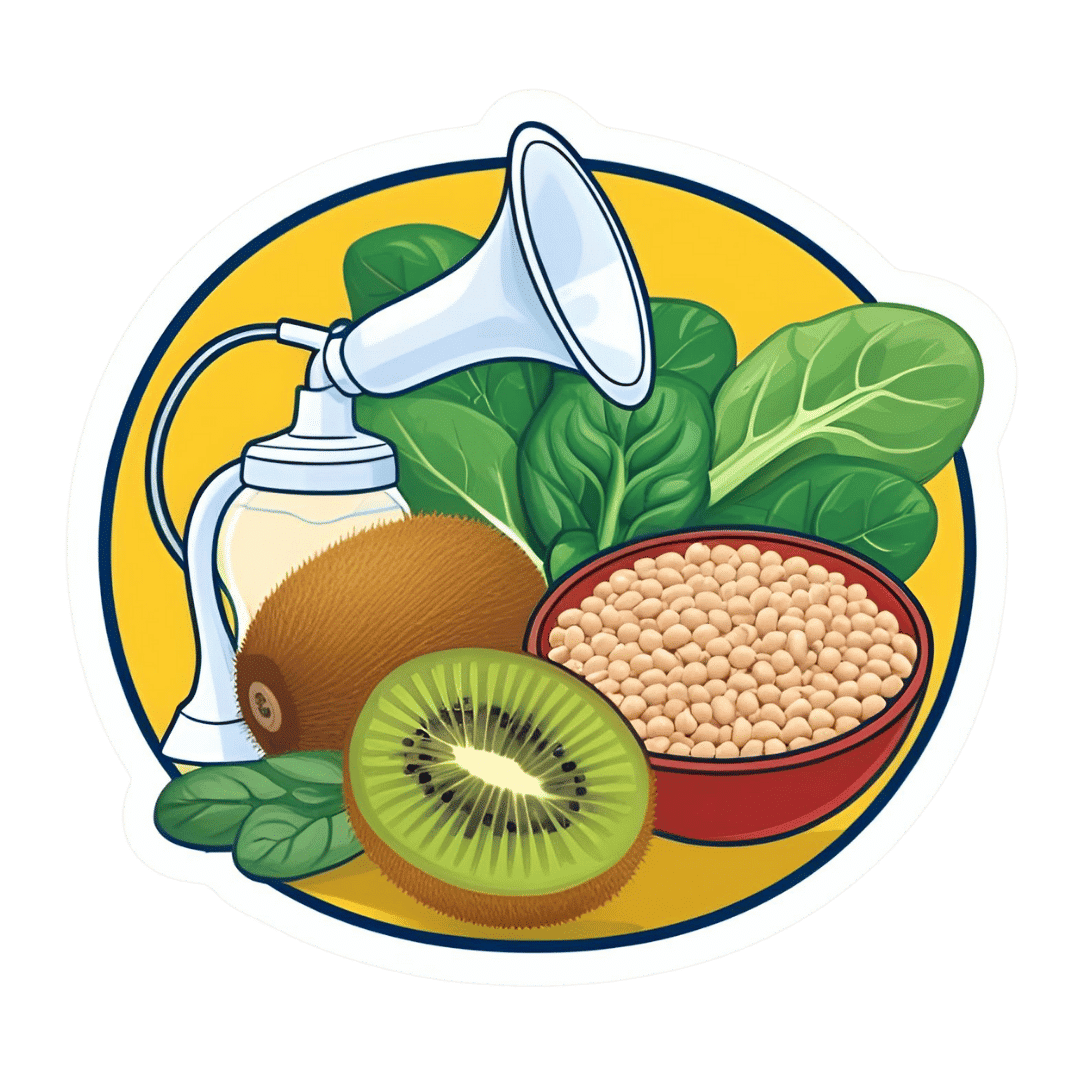

The Many Benefits Of Taking PQQ

10almonds is reader-supported. We may, at no cost to you, receive a portion of sales if you purchase a product through a link in this article.

We’re going to start this one by quoting directly from the journal “Current Research in Food Science”, because it provides a very convenient list of benefits for us to look at:

- PQQ is a potent antioxidant that supports redox balance and mitochondrial function, vital for energy and health.

- PQQ contributes to lipid metabolism regulation, indicating potential benefits for energy management.

- PQQ supplementation is linked to weight control, improved insulin sensitivity, and may help prevent metabolic disorders.

- PQQ may attenuate inflammation, bolster cognitive and cardiovascular health, and potentially assist in cancer therapies.

Future research should investigate PQQ dosages, long-term outcomes, and its potential for metabolic and cognitive health. The translation of PQQ research into clinical practice could offer new strategies for managing metabolic disorders, enhancing cognitive health, and potentially extending lifespan.

What is it?

It’s a redox-active (and thus antioxidant) quinone molecule, and essential vitamin co-factor, that not only helps mitochondria to do their thing, but also supports the creation of new mitochondria.

For more detail, you can read all about that here: Pyrroloquinoline Quinone, a Redox-Active o-Quinone, Stimulates Mitochondrial Biogenesis by Activating the SIRT1/PGC-1α Signaling Pathway

It’s first and foremost made by bacteria, and/but it’s present in many foods, including kiwi fruit, spinach, celery, soybeans, human breast milk, and mouse breast milk.

You may be wondering why “mouse breast milk” makes the list. The causal reason is simply that research scientists do a lot of work with mice, and so it was discovered. If you would argue it is not a food because it is breast milk from another species, then ask yourself if you would have said the same if it came from a cow or goat—only social convention makes it different!

For any vegans reading: ok, you get a free pass on this one :p

This information sourced from: Pyrroloquinoline Quinone: Its Profile, Effects on the Liver and Implications for Health and Disease Prevention

On which note…

Against non-alcoholic fatty liver disease

From the above-linked study:

❝Antioxidant supplementation can reverse hepatic steatosis, suggesting dietary antioxidants might have potential as therapeutics for nonalcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) or nonalcoholic steatohepatitis (NASH).

An extraordinarily potent dietary antioxidant is pyrroloquinoline quinone (PQQ). PQQ is a ubiquitous, natural, and essential bacterial cofactor found in soil, plants, and interstellar dust. The major source of PQQ in mammals is dietary; it is common in leafy vegetables, fruits, and legumes, especially soy, and is found in high concentrations in human and mouse breast milk.

This chapter reviews chemical and biological properties enabling PQQ’s pleiotropic actions, which include modulating multiple signaling pathways directly (NF-κB, JNK, JAK-STAT) and indirectly (Wnt, Notch, Hedgehog, Akt) to improve liver pathophysiology. The role of PQQ in the microbiome is discussed, as PQQ-secreting probiotics ameliorate oxidative stress–induced injury systemwide. A limited number of human trials are summarized, showing safety and efficacy of PQQ❞

…which is all certainly good to see.

Source: Ibid.

Against obesity

And especially, against metabolic obesity, in other words, against the accumulation of visceral and hepatic fat, which are much much worse for the health than subcutaneous fat (that’s the fat you can physically squish and squeeze from the outside with your hands):

❝In addition to inhibiting lipogenesis, PQQ can increase mitochondria number and function, leading to improved lipid metabolism. Besides diet-induced obesity, PQQ ameliorates programing obesity of the offspring through maternal supplementation and alters gut microbiota, which reduces obesity risk.

In obesity progression, PQQ mitigates mitochondrial dysfunction and obesity-associated inflammation, resulting in the amelioration of the progression of obesity co-morbidities, including non-alcoholic fatty liver disease, chronic kidney disease, and Type 2 diabetes.

Overall, PQQ has great potential as an anti-obesity and preventive agent for obesity-related complications.❞

Read in full: Pyrroloquinoline-quinone to reduce fat accumulation and ameliorate obesity progression

Against aging

This one’s particularly interesting, because…

❝PQQ’s modulation of lactate acid and perhaps other dehydrogenases enhance NAD+-dependent sirtuin activity, along with the sirtuin targets, such as PGC-1α, NRF-1, NRF-2 and TFAM; thus, mediating mitochondrial functions. Taken together, current observations suggest vitamin-like PQQ has strong potential as a potent therapeutic nutraceutical❞

If you’re not sure about what NAD+ is, you can read about it here: NAD+ Against Aging

And if you’re not sure what sirtuins do, you can read about those here: Dr. Greger’s Anti-Aging Eight ← it’s at the bottom!

Want to try some?

As mentioned, it can be found in certain foods, but to guarantee getting enough, and/or if you’d simply like it in supplement form, here’s an example product on Amazon 😎

Enjoy!

Share This Post

-

Healthy Habits For Your Heart – by Monique Tello

10almonds is reader-supported. We may, at no cost to you, receive a portion of sales if you purchase a product through a link in this article.

Did you guess we’d review this one today? Well, you’ve already had a taste of what Dr. Tello has to offer, but if you want to take your heart health seriously, this incredibly accessible guide is excellent.

Because Dr. Tello doesn’t assume prior knowledge, the first part of the book (the first three chapters) are given over to “heart and habit basics”—heart science, the effect your lifestyle can have on such, and how to change your habits.

The second part of the book is rather larger, and addresses changing foundational habits, nutrition habits, weight loss/maintenance, healthy activity habits, and specifically addressing heart-harmful habits (especially drinking, smoking, and the like).

She then follows up with a section of recipes, references, and other useful informational appendices.

The writing style throughout is super simple and clear, even when giving detailed clinical information. This isn’t a dusty old doctor who loves the sound of their own jargon, this is good heart health rendered as easy and accessible as possible to all.

Share This Post

Related Posts

-

Having an x-ray to diagnose knee arthritis might make you more likely to consider potentially unnecessary surgery

10almonds is reader-supported. We may, at no cost to you, receive a portion of sales if you purchase a product through a link in this article.

Osteoarthritis is a leading cause of chronic pain and disability, affecting more than two million Australians.

Routine x-rays aren’t recommended to diagnose the condition. Instead, GPs can make a diagnosis based on symptoms and medical history.

Yet nearly half of new patients with knee osteoarthritis who visit a GP in Australia are referred for imaging. Osteoarthritis imaging costs the health system A$104.7 million each year.

Our new study shows using x-rays to diagnose knee osteoarthritis can affect how a person thinks about their knee pain – and can prompt them to consider potentially unnecessary knee replacement surgery.

pikselstock/Shutterstock What happens when you get osteoarthritis?

Osteoarthritis arises from joint changes and the joint working extra hard to repair itself. It affects the entire joint, including the bones, cartilage, ligaments and muscles.

It is most common in older adults, people with a high body weight and those with a history of knee injury.

Many people with knee osteoarthritis experience persistent pain and have difficulties with everyday activities such as walking and climbing stairs.

How is it treated?

In 2021–22, more than 53,000 Australians had knee replacement surgery for osteoarthritis.

Hospital services for osteoarthritis, primarily driven by joint replacement surgery, cost $3.7 billion in 2020–21.

While joint replacement surgery is often viewed as inevitable for osteoarthritis, it should only be considered for those with severe symptoms who have already tried appropriate non-surgical treatments. Surgery carries the risk of serious adverse events, such as blood clot or infection, and not everyone makes a full recovery.

Most people with knee osteoarthritis can manage it effectively with:

- education and self-management

- exercise and physical activity

- weight management (if necessary)

- medicines for pain relief (such as paracetamol and non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs).

Debunking a common misconception

A common misconception is that osteoarthritis is caused by “wear and tear”.

However, research shows the extent of structural changes seen in a joint on an x-ray does not reflect the level of pain or disability a person experiences, nor does it predict how symptoms will change.

Some people with minimal joint changes have very bad symptoms, while others with more joint changes have only mild symptoms. This is why routine x-rays aren’t recommended for diagnosing knee osteoarthritis or guiding treatment decisions.

Instead, guidelines recommend a “clinical diagnosis” based on a person’s age (being 45 years or over) and symptoms: experiencing joint pain with activity and, in the morning, having no joint-stiffness or stiffness that lasts less than 30 minutes.

Despite this, many health professionals in Australia continue to use x-rays to diagnose knee osteoarthritis. And many people with osteoarthritis still expect or want them.

What did our study investigate?

Our study aimed to find out if using x-rays to diagnose knee osteoarthritis affects a person’s beliefs about osteoarthritis management, compared to a getting a clinical diagnosis without x-rays.

We recruited 617 people from across Australia and randomly assigned them to watch one of three videos. Each video showed a hypothetical consultation with a general practitioner about knee pain.

People with knee osteoarthritis can have difficulties getting down stairs. beeboys/Shutterstock One group received a clinical diagnosis of knee osteoarthritis based on age and symptoms, without being sent for an x-ray.

The other two groups had x-rays to determine their diagnosis (the doctor showed one group their x-ray images and not the other).

After watching their assigned video, participants completed a survey about their beliefs about osteoarthritis management.

What did we find?

People who received an x-ray-based diagnosis and were shown their x-ray images had a 36% higher perceived need for knee replacement surgery than those who received a clinical diagnosis (without x-ray).

They also believed exercise and physical activity could be more harmful to their joint, were more worried about their condition worsening, and were more fearful of movement.

Interestingly, people were slightly more satisfied with an x-ray-based diagnosis than a clinical diagnosis.

This may reflect the common misconception that osteoarthritis is caused by “wear and tear” and an assumption that the “damage” inside the joint needs to be seen to guide treatment.

What does this mean for people with osteoarthritis?

Our findings show why it’s important to avoid unnecessary x-rays when diagnosing knee osteoarthritis.

While changing clinical practice can be challenging, reducing unnecessary x-rays could help ease patient anxiety, prevent unnecessary concern about joint damage, and reduce demand for costly and potentially unnecessary joint replacement surgery.

It could also help reduce exposure to medical radiation and lower health-care costs.

Previous research in osteoarthritis, as well as back and shoulder pain, similarly shows that when health professionals focus on joint “wear and tear” it can make patients more anxious about their condition and concerned about damaging their joints.

If you have knee osteoarthritis, know that routine x-rays aren’t needed for diagnosis or to determine the best treatment for you. Getting an x-ray can make you more concerned and more open to surgery. But there are a range of non-surgical options that could reduce pain, improve mobility and are less invasive.

Belinda Lawford, Senior Research Fellow in Physiotherapy, The University of Melbourne; Kim Bennell, Professor of Physiotherapy, The University of Melbourne; Rana Hinman, Professor in Physiotherapy, The University of Melbourne, and Travis Haber, Postdoctoral Research Fellow in Physiotherapy, The University of Melbourne

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Don’t Forget…

Did you arrive here from our newsletter? Don’t forget to return to the email to continue learning!

Learn to Age Gracefully

Join the 98k+ American women taking control of their health & aging with our 100% free (and fun!) daily emails:

-

How to Do the Work – by Dr. Nicole LaPera

10almonds is reader-supported. We may, at no cost to you, receive a portion of sales if you purchase a product through a link in this article.

We have reviewed some self-therapy books before, and they chiefly have focused on CBT and mindfulness, which are great. This one’s different.

Dr. Nicole LaPera has a bolder vision for what we can do for ourselves. Rather than giving us some worksheets for unraveling cognitive distortions or clearing up automatic negative thoughts, she bids us treat the cause, rather than the symptom.

For most of us, this will be the life we have led. Now, we cannot change the parenting style(s) we received (or didn’t), get a redo on childhood, avoid mistakes we made in our adolescence, or face adult life with the benefit of experience we gained right after we needed it most. But we can still work on those things if we just know how.

The subtitle of this book promsies that the reader can/will “recognise your patterns, heal from your past, and create your self”.

That’s accurate, for the content of the book and the advice it gives.

Dr. LaPera’s focus is on being our own best healer, and reparenting our own inner child. Giving each of us the confidence in ourself; the love and care and/but also firm-if-necessary direction that a (good) parent gives a child, and the trust that a secure child will have in the parent looking after them. Doing this for ourselves, Dr. LaPera holds, allows us to heal from traumas we went through when we perhaps didn’t quite have that, and show up for ourselves in a way that we might not have thought about before.

If the book has a weak point, it’s that many of the examples given are from Dr. LaPera’s own life and experience, so how relatable the specific examples will be to any given reader may vary. But, the principles and advices stand the same regardless.

Bottom line: if you’d like to try self-therapy on a deeper level than CBT worksheets, this book is an excellent primer.

Click here to check out How To Do The Work, and empower yourself to indeed do the work!

Don’t Forget…

Did you arrive here from our newsletter? Don’t forget to return to the email to continue learning!

Learn to Age Gracefully

Join the 98k+ American women taking control of their health & aging with our 100% free (and fun!) daily emails:

-

Powered by Plants – by Ocean Robbins & Nichole Dandrea-Russert

10almonds is reader-supported. We may, at no cost to you, receive a portion of sales if you purchase a product through a link in this article.

Of the two authors, the former is a professional public speaker, and the latter is a professional dietician. As a result, we get a book that is polished and well-presented, while actually having a core of good solid science (backed up with plenty of references).

There’s an introductory section that’s all about the “notable nutrients”, that will be focused on in the ingredients choices for the recipes in the rest of the book.

The recipes themselves are simple enough to do quickly, yet interesting enough that you’ll want to do them, and certainly they contain all the plant-based nutrient-density you might expect.

Bottom line: if you’d like to expand your plant-based cooking with a focus on nutrition and ease without sacrificing fun, then this is a great cookbook for that.

Click here to check out Powered by Plants, and get powered by plants!

Don’t Forget…

Did you arrive here from our newsletter? Don’t forget to return to the email to continue learning!

Learn to Age Gracefully

Join the 98k+ American women taking control of their health & aging with our 100% free (and fun!) daily emails: