Why are tall people more likely to get cancer? What we know, don’t know and suspect

10almonds is reader-supported. We may, at no cost to you, receive a portion of sales if you purchase a product through a link in this article.

People who are taller are at greater risk of developing cancer. The World Cancer Research Fund reports there is strong evidence taller people have a higher chance of of developing cancer of the:

- pancreas

- large bowel

- uterus (endometrium)

- ovary

- prostate

- kidney

- skin (melanoma) and

- breast (pre- and post-menopausal).

But why? Here’s what we know, don’t know and suspect.

A well established pattern

The UK Million Women Study found that for 15 of the 17 cancers they investigated, the taller you are the more likely you are to have them.

It found that overall, each ten-centimetre increase in height increased the risk of developing a cancer by about 16%. A similar increase has been found in men.

Let’s put that in perspective. If about 45 in every 10,000 women of average height (about 165 centimetres) develop cancer each year, then about 52 in each 10,000 women who are 175 centimetres tall would get cancer. That’s only an extra seven cancers.

So, it’s actually a pretty small increase in risk.

Another study found 22 of 23 cancers occurred more commonly in taller than in shorter people.

Why?

The relationship between height and cancer risk occurs across ethnicities and income levels, as well as in studies that have looked at genes that predict height.

These results suggest there is a biological reason for the link between cancer and height.

While it is not completely clear why, there are a couple of strong theories.

The first is linked to the fact a taller person will have more cells. For example, a tall person probably has a longer large bowel with more cells and thus more entries in the large bowel cancer lottery than a shorter person.

Scientists think cancer develops through an accumulation of damage to genes that can occur in a cell when it divides to create new cells.

The more times a cell divides, the more likely it is that genetic damage will occur and be passed onto the new cells.

The more damage that accumulates, the more likely it is that a cancer will develop.

A person with more cells in their body will have more cell divisions and thus potentially more chance that a cancer will develop in one of them.

Some research supports the idea having more cells is the reason tall people develop cancer more and may explain to some extent why men are more likely to get cancer than women (because they are, on average, taller than women).

However, it’s not clear height is related to the size of all organs (for example, do taller women have bigger breasts or bigger ovaries?).

One study tried to assess this. It found that while organ mass explained the height-cancer relationship in eight of 15 cancers assessed, there were seven others where organ mass did not explain the relationship with height.

It is worth noting this study was quite limited by the amount of data they had on organ mass.

Another theory is that there is a common factor that makes people taller as well as increasing their cancer risk.

One possibility is a hormone called insulin-like growth factor 1 (IGF-1). This hormone helps children grow and then continues to have an important role in driving cell growth and cell division in adults.

This is an important function. Our bodies need to produce new cells when old ones are damaged or get old. Think of all the skin cells that come off when you use a good body scrub. Those cells need to be replaced so our skin doesn’t wear out.

However, we can get too much of a good thing. Some studies have found people who have higher IGF-1 levels than average have a higher risk of developing breast or prostate cancer.

But again, this has not been a consistent finding for all cancer types.

It is likely that both explanations (more cells and more IGF-1) play a role.

But more research is needed to really understand why taller people get cancer and whether this information could be used to prevent or even treat cancers.

I’m tall. What should I do?

If you are more LeBron James than Lionel Messi when it comes to height, what can you do?

Firstly, remember height only increases cancer risk by a very small amount.

Secondly, there are many things all of us can do to reduce our cancer risk, and those things have a much, much greater effect on cancer risk than height.

We can take a look at our lifestyle. Try to:

- eat a healthy diet

- exercise regularly

- maintain a healthy weight

- be careful in the sun

- limit alcohol consumption.

And, most importantly, don’t smoke!

If we all did these things we could vastly reduce the amount of cancer.

You can also take part in cancer screening programs that help pick up cancers of the breast, cervix and bowel early so they can be treated successfully.

Finally, take heart! Research also tells us that being taller might just reduce your chance of having a heart attack or stroke.

Susan Jordan, Associate Professor of Epidemiology, The University of Queensland and Karen Tuesley, Postdoctoral Research Fellow, School of Public Health, The University of Queensland

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Don’t Forget…

Did you arrive here from our newsletter? Don’t forget to return to the email to continue learning!

Recommended

Learn to Age Gracefully

Join the 98k+ American women taking control of their health & aging with our 100% free (and fun!) daily emails:

-

Most adults will gain half a kilo this year – and every year. Here’s how to stop ‘weight creep’

10almonds is reader-supported. We may, at no cost to you, receive a portion of sales if you purchase a product through a link in this article.

As we enter a new year armed with resolutions to improve our lives, there’s a good chance we’ll also be carrying something less helpful: extra kilos. At least half a kilogram, to be precise.

“Weight creep” doesn’t have to be inevitable. Here’s what’s behind this sneaky annual occurrence and some practical steps to prevent it.

Allgo/Unsplash Small gains add up

Adults tend to gain weight progressively as they age and typically gain an average of 0.5 to 1kg every year.

While this doesn’t seem like much each year, it amounts to 5kg over a decade. The slow-but-steady nature of weight creep is why many of us won’t notice the extra weight gained until we’re in our fifties.

Why do we gain weight?

Subtle, gradual lifestyle shifts as we progress through life and age-related biological changes cause us to gain weight. Our:

- activity levels decline. Longer work hours and family commitments can see us become more sedentary and have less time for exercise, which means we burn fewer calories

- diets worsen. With frenetic work and family schedules, we sometimes turn to pre-packaged and fast foods. These processed and discretionary foods are loaded with hidden sugars, salts and unhealthy fats. A better financial position later in life can also result in more dining out, which is associated with a higher total energy intake

- sleep decreases. Busy lives and screen use can mean we don’t get enough sleep. This disturbs our body’s energy balance, increasing our feelings of hunger, triggering cravings and decreasing our energy

Insufficient sleep can increase our appetite. Craig Adderley/Pexels - stress increases. Financial, relationship and work-related stress increases our body’s production of cortisol, triggering food cravings and promoting fat storage

- metabolism slows. Around the age of 40, our muscle mass naturally declines, and our body fat starts increasing. Muscle mass helps determine our metabolic rate, so when our muscle mass decreases, our bodies start to burn fewer calories at rest.

We also tend to gain a small amount of weight during festive periods – times filled with calorie-rich foods and drinks, when exercise and sleep are often overlooked. One study of Australian adults found participants gained 0.5 kilograms on average over the Christmas/New Year period and an average of 0.25 kilograms around Easter.

Why we need to prevent weight creep

It’s important to prevent weight creep for two key reasons:

1. Weight creep resets our body’s set point

Set-point theory suggests we each have a predetermined weight or set point. Our body works to keep our weight around this set point, adjusting our biological systems to regulate how much we eat, how we store fat and expend energy.

When we gain weight, our set point resets to the new, higher weight. Our body adapts to protect this new weight, making it challenging to lose the weight we’ve gained.

But it’s also possible to lower your set point if you lose weight gradually and with an interval weight loss approach. Specifically, losing weight in small manageable chunks you can sustain – periods of weight loss, followed by periods of weight maintenance, and so on, until you achieve your goal weight.

Holidays can also come with weight gain. Zan Lazarevic/Unsplash 2. Weight creep can lead to obesity and health issues

Undetected and unmanaged weight creep can result in obesity which can increase our risk of heart disease, strokes, type 2 diabetes, osteoporosis and several types of cancers (including breast, colorectal, oesophageal, kidney, gallbladder, uterine, pancreatic and liver).

A large study examined the link between weight gain from early to middle adulthood and health outcomes later in life, following people for around 15 years. It found those who gained 2.5 to 10kg over this period had an increased incidence of type 2 diabetes, heart disease, strokes, obesity-related cancer and death compared to participants who had maintained a stable weight.

Fortunately, there are steps we can take to build lasting habits that will make weight creep a thing of the past.

7 practical steps to prevent weight creep

1. Eat from big to small

Aim to consume most of your food earlier in the day and taper your meal sizes to ensure dinner is the smallest meal you eat.

A low-calorie or small breakfast leads to increased feelings of hunger, specifically appetite for sweets, across the course of the day.

We burn the calories from a meal 2.5 times more efficiently in the morning than in the evening. So emphasising breakfast over dinner is also good for weight management.

Aim to consume bigger breakfasts and smaller dinners. Michael Burrows/Pexels 2. Use chopsticks, a teaspoon or an oyster fork

Sit at the table for dinner and use different utensils to encourage eating more slowly.

This gives your brain time to recognise and adapt to signals from your stomach telling you you’re full.

3. Eat the full rainbow

Fill your plate with vegetables and fruits of different colours first to support eating a high-fibre, nutrient-dense diet that will keep you feeling full and satisfied.

Meals also need to be balanced and include a source of protein, wholegrain carbohydrates and healthy fat to meet our dietary needs – for example, eggs on wholegrain toast with avocado.

4. Reach for nature first

Retrain your brain to rely on nature’s treats – fresh vegetables, fruit, honey, nuts and seeds. In their natural state, these foods release the same pleasure response in the brain as ultra-processed and fast foods, helping you avoid unnecessary calories, sugar, salt and unhealthy fats.

5. Choose to move

Look for ways to incorporate incidental activity into your daily routine – such as taking the stairs instead of the lift – and boost your exercise by challenging yourself to try a new activity.

Just be sure to include variety, as doing the same activities every day often results in boredom and avoidance.

Try new activities or sports to keep your interest up. Cottonbro Studio/Pexels 6. Prioritise sleep

Set yourself a goal of getting a minimum of seven hours of uninterrupted sleep each night, and help yourself achieve it by avoiding screens for an hour or two before bed.

7. Weigh yourself regularly

Getting into the habit of weighing yourself weekly is a guaranteed way to help avoid the kilos creeping up on us. Aim to weigh yourself on the same day, at the same time and in the same environment each week and use the best quality scales you can afford.

At the Boden Group, Charles Perkins Centre, we are studying the science of obesity and running clinical trials for weight loss. You can register here to express your interest.

Nick Fuller, Clinical Trials Director, Department of Endocrinology, RPA Hospital, University of Sydney

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Share This Post

-

100 No-Equipment Workouts – by Neila Rey

10almonds is reader-supported. We may, at no cost to you, receive a portion of sales if you purchase a product through a link in this article.

For those of us who for whatever reason prefer to exercise at home rather than at the gym, we must make do with what exercise equipment we can reasonably install in our homes. This book deals with that from the ground upwards—literally!

If you have a few square meters of floorspace (and a ceiling that’s not too low, for exercises that involve any kind of jumping), then all 100 of these zero-equipment exercises are at-home options.

As to what kinds of exercises they are, they each marked as being one or both of “cardio” and “strength”.

They’re also marked as being of “difficulty level” 1, 2, or 3, so that someone who hasn’t exercised in a while (or hasn’t exercised like this at all), can know where best to start, and how best to progress.

The exercises come with clear explanations in the text, and clear line-drawing illustrations of how to do each exercise. Really, they could not be clearer; this is top quality pragmatism, and reads like a military manual.

Bottom line: whatever your strength and fitness goals, this book can see you well on your way to them (if not outright get you there already in many cases). It’s also an excellent “all-rounder” for full-body workouts.

Share This Post

-

What’s in the supplements that claim to help you cut down on bathroom breaks? And do they work?

10almonds is reader-supported. We may, at no cost to you, receive a portion of sales if you purchase a product through a link in this article.

With one in four Australian adults experiencing problems with incontinence, some people look to supplements for relief.

With ingredients such as pumpkin seed oil and soybean extract, a range of products promise relief from frequent bathroom trips.

But do they really work? Let’s sift through the claims and see what the science says about their efficacy.

Christian Moro/Shutterstock What is incontinence?

Incontinence is the involuntary loss of bladder or bowel control, leading to the unintentional leakage of urine or faeces. It can range from occasional minor leaks to a complete inability to control urination and defecation.

This condition can significantly impact daily activities and quality of life, and affects women more often than it affects men.

Some people don’t experience bladder leakage but can sometimes feel an urgent need to go to the bathroom. This is known as overactive bladder syndrome, and occurs when the muscles around the bladder tighten on their own, which greatly reduces its capacity. The result is the person feels the need to go to the bathroom much more frequently.

There are many potential causes of incontinence and overactive bladders, including menopause, pregnancy and child birth, urinary tract infections, pelvic floor disorders, and an enlarged prostate. Conditions such as diabetes, neurological disorders and certain medications (such as diuretics, sleeping pills, antidepressants and blood-pressure drugs) can also contribute.

While pelvic muscle rehabilitation and behavioural techniques for bladder retraining can be helpful, some people are interested in pharmaceutical solutions.

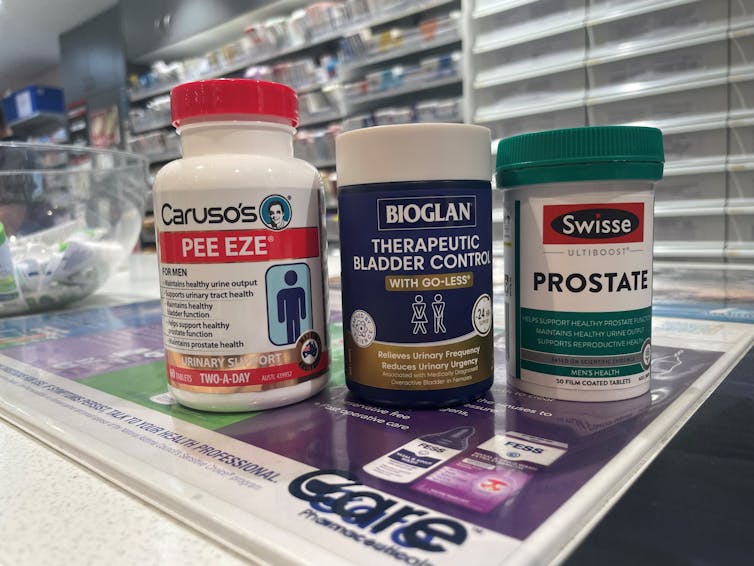

What’s in these products?

A number of supplements are available in Australia that include ingredients used in traditional medicine for urinary incontinence and overactive bladders. The three most common ingredients are:

- Cucurbita pepo (pumpkin seed extract)

- glycine max (soybean extract)

- an extract from the bark of the Crateva magna or nurvala (Varuna) tree.

The supplements have common ingredients. Author How are they supposed to work?

Pumpkin seeds are rich in plant sterols that are thought to reduce the testosterone-related enlargement of the prostate, as well as having broader anti-inflammatory effects. The seed extracts can also contain oleic acid, which may help increase bladder capacity by relaxing the muscles around the organ.

Soybean extracts are rich in isoflavones, especially daidzen and genistein. Like olieic acid, these are thought to act on the muscles around the bladder. Because isoflavones are similar in structure to the female hormone oestrogen, soy extracts may be most beneficial for postmenopausal women who have overactive bladders.

Crateva extract is rich in lupeol- and sterol-based chemicals which have strong anti-inflammatory effects. This has benefits not just for enlarged prostates but possibly also for reducing urinary tract infections.

Do they actually work?

It’s important to note that the government has only approved these types of supplements as “listed medicines”. This means the ingredients have only been assessed for safety. The companies behind the products have not had to provide evidence they actually work.

A 2014 clinical trial examined a combined pumpkin seed and soybean extract called cucurflavone on people with overactive bladders. The 120 participants received either a placebo or a daily 1,000mg dose of the herbal mixture over a period of 12 weeks.

By the end of study, those in the cucurflavone group went to the bathroom around three fewer times per day, compared with people in the control group, who only went to the bathroom on average one fewer time each day.

In a different trial, researchers examined a combination of Crateva bark extract with herbal extracts of horsetail and Japanese evergreen spicebush, called Urox.

For the 150 participants, the Urox formulation helped participants go to the bathroom less frequently when compared with placebo treatment.

After eight weeks of treatment, participants in the placebo group were going to the bathroom to urinate 11 times per day. Those in the Urox group were only going around to 7.5 times per day. And those who took Urox also needed to go to the bathroom one fewer time during the night.

Finally, another study also examined a Creteva, horsetail and Japanese spicebush combination, but this time in children. They were given either a 420mg dose of the supplement or a placebo, and then monitored for how many times they wet the bed.

After two months of taking the supplement, slightly more than 40% of the 24 kids in the supplement group wet the bed less often.

While these results may look promising, there are considerable limitations to the studies which means the data may not be reliable. For example, the trials didn’t include enough participants to have reliable data. To conclusively provide efficacy, final-stage clinical trials require data for between 300 and 3,000 patients.

From the studies, it is also not clear whether some participants were also taking other medicines as well as the supplement. This is important, as medications can interfere with how the supplements work, potentially making them less or more effective.

What if you want to take them?

If you have incontinence or an overactive bladder, you should always discuss this with your doctor, as it may due to a serious or treatable underlying condition.

Otherwise, your GP may give you strategies or exercises to improve your bladder control, prescribe medications or devices, or refer you to a specialist.

If you do decide to take a supplement, discuss this with your doctor and local pharmacist so they can check that any product you choose will not interfere with any other medications you may be taking.

Nial Wheate, Professor of Pharmaceutical Chemistry, Macquarie University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Share This Post

Related Posts

-

Hitting the beach? Here are some dangers to watch out for – plus 10 essentials for your first aid kit

10almonds is reader-supported. We may, at no cost to you, receive a portion of sales if you purchase a product through a link in this article.

Summer is here and for many that means going to the beach. You grab your swimmers, beach towel and sunscreen then maybe check the weather forecast. Did you think to grab a first aid kit?

The vast majority of trips to the beach will be uneventful. However, if trouble strikes, being prepared can make a huge difference to you, a loved one or a stranger.

So, what exactly should you be prepared for?

FTiare/Shutterstock Knowing the dangers

The first step in being prepared for the beach is to learn about where you are going and associated levels of risk.

In Broome, you are more likely to be bitten by a dog at the beach than stung by an Irukandji jellyfish.

In Byron Bay, you are more likely to come across a brown snake than a shark.

In the summer of 2023–24, Surf Life Saving Australia reported more than 14 million Australian adults visited beaches. Surf lifesavers, lifeguards and lifesaving services performed 49,331 first aid treatments across 117 local government areas around Australia. Surveys of beach goers found perceptions of common beach hazards include rips, tropical stingers, sun exposure, crocodiles, sharks, rocky platforms and waves.

Sun and heat exposure are likely the most common beach hazard. The Cancer Council has reported that almost 1.5 million Australians surveyed during summer had experienced sunburn during the previous week. Without adequate fluid intake, heat stroke can also occur.

Lacerations and abrasions are a further common hazard. While surfboards, rocks, shells and litter might seem more dangerous, the humble beach umbrella has been implicated in thousands of injuries.

Sprains and fractures are also associated with beach activities. A 2022 study linked data from hospital, ambulance and Surf Life Saving cases on the Sunshine Coast over six years and found 79 of 574 (13.8%) cervical spine injuries occurred at the beach. Surfing, smaller wave heights and shallow water diving were the main risks.

Rips and rough waves present a higher risk at areas of unpatrolled beach, including away from surf lifesaving flags. Out of 150 coastal drowning deaths around Australia in 2023–24, nearly half were during summer. Of those deaths:

- 56% occurred at the beach

- 31% were rip-related

- 86% were male, and

- 100% occurred away from patrolled areas.

People who had lived in Australia for less than two years were more worried about the dangers, but also more likely to be caught in a rip.

Safety Beach on Victoria’s Mornington Peninsula. Still bring your first aid essentials though. Julia Kuleshova/Shutterstock Knowing your DR ABCs

So, beach accidents can vary by type, severity and impact. How you respond will depend on your level of first aid knowledge, ability and what’s in your first aid kit.

A first aid training company survey of just over 1,000 Australians indicated 80% of people agree cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR) is the most important skill to learn, but nearly half reported feeling intimidated by the prospect.

CPR training covers an established checklist for emergency situations. Using the acronym “DR ABC” means checking for:

- Danger

- Response

- Airway

- Breathing

- Circulation

A complete first aid course will provide a range of skills to build confidence and be accredited by the national regulator, the Australian Skills Quality Authority.

What to bring – 10 first aid essentials

Whether you buy a first aid kit or put together you own, it should include ten essential items in a watertight, sealable container:

- Band-Aids for small cuts and abrasions

- sterile gauze pads

- bandages (one small one for children, one medium crepe to hold on a dressing or support strains or sprains, and one large compression bandage for a limb)

- large fabric for sling

- a tourniquet bandage or belt to restrict blood flow

- non-latex disposable gloves

- scissors and tweezers

- medical tape

- thermal or foil blanket

- CPR shield or breathing mask.

Before you leave for the beach, check the expiry dates of any sunscreen, solutions or potions you choose to add.

If you’re further from help

If you are travelling to a remote or unpatrolled beach, your kit should also contain:

- sterile saline solution to flush wounds or rinse eyes

- hydrogel or sunburn gel

- an instant cool pack

- paracetamol and antihistamine medication

- insect repellent.

Make sure you carry any “as-required” medications, such as a Ventolin puffer for asthma or an EpiPen for severe allergy.

Vinegar is no longer recommended for most jellyfish stings, including Blue Bottles. Hot water is advised instead.

In remote areas, also look out for Emergency Response Beacons. Located in high-risk spots, these allow bystanders to instantly activate the surf emergency response system.

If you have your mobile phone or a smart watch with GPS function, make sure it is charged and switched on and that you know how to use it to make emergency calls.

First aid kits suitable for the beach range in price from $35 to over $120. Buy these from certified first aid organisations such as Surf Lifesaving Australia, Australian Red Cross, St John Ambulance or Royal Life Saving. Kits that come with a waterproof sealable bag are recommended.

Be prepared this summer for your trip to the beach and pack your first aid kit. Take care and have fun in the sun.

Andrew Woods, Lecturer, Nursing, Faculty of Health, Southern Cross University and Willa Maguire, Associate Lecturer in Nursing, Southern Cross University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Don’t Forget…

Did you arrive here from our newsletter? Don’t forget to return to the email to continue learning!

Learn to Age Gracefully

Join the 98k+ American women taking control of their health & aging with our 100% free (and fun!) daily emails:

-

In This Oklahoma Town, Most Everyone Knows Someone Who’s Been Sued by the Hospital

10almonds is reader-supported. We may, at no cost to you, receive a portion of sales if you purchase a product through a link in this article.

McALESTER, Okla. — It took little more than an hour for Deborah Hackler to dispense with the tall stack of debt collection lawsuits that McAlester Regional Medical Center recently brought to small-claims court in this Oklahoma farm community.

Hackler, a lawyer who sues patients on behalf of the hospital, buzzed through 51 cases, all but a handful uncontested, as is often the case. She bantered with the judge as she secured nearly $40,000 in judgments, plus 10% in fees for herself, according to court records.

It’s a payday the hospital and Hackler have shared frequently over the past three decades, records show. The records indicate McAlester Regional Medical Center and an affiliated clinic have filed close to 5,000 debt collection cases since the early 1990s, most often represented by the father-daughter law firm of Hackler & Hackler.

Some of McAlester’s 18,000 residents have been taken to court multiple times. A deputy at the county jail and her adult son were each sued recently, court records show. New mothers said they compare stories of their legal run-ins with the medical center.

“There’s a lot that’s not right,” Sherry McKee, a dorm monitor at a tribal boarding school outside McAlester, said on the courthouse steps after the hearing. The hospital has sued her three times, most recently over a $3,375 bill for what she said turned out to be vertigo.

In recent years, major health systems in Virginia, North Carolina, and elsewhere have stopped suing patients following news reports about lawsuits. And several states, such as Maryland and New York, have restricted the legal actions hospitals can take against patients.

But with some 100 million people in the U.S. burdened by health care debt, medical collection cases still clog courtrooms across the country, researchers have found. In places like McAlester, a hospital’s debt collection machine can hum away quietly for years, helped along by powerful people in town. An effort to limit hospital lawsuits failed in the Oklahoma Legislature in 2021.

In McAlester, the lawsuits have provided business for some, such as the Adjustment Bureau, a local collection agency run out of a squat concrete building down the street from the courthouse, and for Hackler, a former president of the McAlester Area Chamber of Commerce. But for many patients and their families, the lawsuits can take a devastating toll, sapping wages, emptying retirement accounts, and upending lives.

McKee said she wasn’t sure how long it would take to pay off the recent judgment. Her $3,375 debt exceeds her monthly salary, she said.

“This affects a large number of people in a small community,” said Janet Roloff, an attorney who has spent years assisting low-income clients with legal issues such as evictions in and around McAlester. “The impact is great.”

Settled more than a century ago by fortune seekers who secured land from the Choctaw Nation to mine coal in the nearby hills, McAlester was once a boom town. Vestiges of that era remain, including a mammoth, 140-foot-tall Masonic temple that looms over the city.

Recent times have been tougher for McAlester, now home by one count to 12 marijuana dispensaries and the state’s death row. The downtown is pockmarked by empty storefronts, including the OKLA theater, which has been dark for decades. Nearly 1 in 5 residents in McAlester and the surrounding county live below the federal poverty line.

The hospital, operated by a public trust under the city’s authority, faces its own struggles. Paint is peeling off the front portico, and weeds poke up through the parking lots. The hospital has operated in the red for years, according to independent audit reports available on the state auditor’s website.

“I’m trying to find ways to get the entire community better care and more care,” said Shawn Howard, the hospital’s chief executive. Howard grew up in McAlester and proudly noted he started his career as a receptionist in the hospital’s physical therapy department. “This is my hometown,” he said. “I am not trying to keep people out of getting care.”

The hospital operates a clinic for low-income patients, whose webpage notes it has “limited appointments” at no cost for patients who are approved for aid. But data from the audits shows the hospital offers very little financial assistance, despite its purported mission to serve the community.

In the 2022 fiscal year, it provided just $114,000 in charity care, out of a total operating budget of more than $100 million, hospital records show. Charity care totaling $2 million or $3 million out of a $100 million budget would be more in line with other U.S. hospitals.

While audits show few McAlester patients get financial aid, many get taken to court.

Renee Montgomery, the city treasurer in an adjoining town and mother of a local police officer, said she dipped into savings she’d reserved for her children and grandchildren after the hospital sued her last year for more than $5,500. She’d gone to the emergency room for chest pain.

Dusty Powell, a truck driver, said he lost his pickup and motorcycle when his wages were garnished after the hospital sued him for almost $9,000. He’d gone to the emergency department for what turned out to be gastritis and didn’t have insurance, he said.

“Everyone in this town probably has a story about McAlester Regional,” said another former patient who spoke on the condition she not be named, fearful to publicly criticize the hospital in such a small city. “It’s not even a secret.”

The woman, who works at an Army munitions plant outside town, was sued twice over bills she incurred giving birth. Her sister-in-law has been sued as well.

“It’s a good-old-boy system,” said the woman, who lowered her voice when the mayor walked into the coffee shop where she was meeting with KFF Health News. Now, she said, she avoids the hospital if her children need care.

Nationwide, most people sued in debt collection cases never challenge them, a response experts say reflects widespread misunderstanding of the legal process and anxiety about coming to court.

At the center of the McAlester hospital’s collection efforts for decades has been Hackler & Hackler.

Donald Hackler was city attorney in McAlester for 13 years in the ’70s and ’80s and a longtime member of the local Lions Club and the Scottish Rite Freemasons.

Daughter Deborah Hackler, who joined the family firm 30 years ago, has been a deacon at the First Presbyterian Church of McAlester and served on the board of the local Girl Scouts chapter, according to the McAlester News-Capital newspaper, which named her “Woman of the Year” in 2007. Since 2001, she also has been a municipal judge in McAlester, hearing traffic cases, including some involving people she has sued on behalf of the hospital, municipal and county court records show.

For years, the Hacklers’ debt collection cases were often heard by Judge James Bland, who has retired from the bench and now sits on the hospital board. Bland didn’t respond to an inquiry for interview.

Hackler declined to speak with KFF Health News after her recent court appearance. “I’m not going to visit with you about a current client,” she said before leaving the courthouse.

Howard, the hospital CEO, said he couldn’t discuss the lawsuits either. He said he didn’t know the hospital took its patients to court. “I had to call and ask if we sue people,” he said.

Howard also said he didn’t know Deborah Hackler. “I never heard her name before,” he said.

Despite repeated public records requests from KFF Health News since September, the hospital did not provide detailed information about its financial arrangement with Hackler.

McAlester Mayor John Browne, who appoints the hospital’s board of trustees, said he, too, didn’t know about the lawsuits. “I hadn’t heard anything about them suing,” he said.

At the century-old courthouse in downtown McAlester, it’s not hard to find the lawsuits, though. Every month or two, another batch fills the docket in the small-claims court, now presided over by Judge Brian McLaughlin.

After court recently, McLaughlin, who is not from McAlester, shook his head at the stream of cases and patients who almost never show up to defend themselves, leaving him to issue judgment after judgment in the hospital’s favor.

“All I can do is follow the law,” said McLaughlin. “It doesn’t mean I like it.”

About This Project

“Diagnosis: Debt” is a reporting partnership between KFF Health News and NPR exploring the scale, impact, and causes of medical debt in America.

The series draws on original polling by KFF, court records, federal data on hospital finances, contracts obtained through public records requests, data on international health systems, and a yearlong investigation into the financial assistance and collection policies of more than 500 hospitals across the country.

Additional research was conducted by the Urban Institute, which analyzed credit bureau and other demographic data on poverty, race, and health status for KFF Health News to explore where medical debt is concentrated in the U.S. and what factors are associated with high debt levels.

The JPMorgan Chase Institute analyzed records from a sampling of Chase credit card holders to look at how customers’ balances may be affected by major medical expenses. And the CED Project, a Denver nonprofit, worked with KFF Health News on a survey of its clients to explore links between medical debt and housing instability.

KFF Health News journalists worked with KFF public opinion researchers to design and analyze the “KFF Health Care Debt Survey.” The survey was conducted Feb. 25 through March 20, 2022, online and via telephone, in English and Spanish, among a nationally representative sample of 2,375 U.S. adults, including 1,292 adults with current health care debt and 382 adults who had health care debt in the past five years. The margin of sampling error is plus or minus 3 percentage points for the full sample and 3 percentage points for those with current debt. For results based on subgroups, the margin of sampling error may be higher.

Reporters from KFF Health News and NPR also conducted hundreds of interviews with patients across the country; spoke with physicians, health industry leaders, consumer advocates, debt lawyers, and researchers; and reviewed scores of studies and surveys about medical debt.

KFF Health News is a national newsroom that produces in-depth journalism about health issues and is one of the core operating programs at KFF—an independent source of health policy research, polling, and journalism. Learn more about KFF.

Subscribe to KFF Health News’ free Morning Briefing.

Don’t Forget…

Did you arrive here from our newsletter? Don’t forget to return to the email to continue learning!

Learn to Age Gracefully

Join the 98k+ American women taking control of their health & aging with our 100% free (and fun!) daily emails:

-

Food for Thought – by Lorraine Perretta

10almonds is reader-supported. We may, at no cost to you, receive a portion of sales if you purchase a product through a link in this article.

What are “brain foods”? If you think for a moment, you can probably list a few. What this book does is better.

As well as providing the promised 50 recipes (which themselves are varied, good, and easy), Perretta explains the science of very many brain-healthy ingredients. Not just that, but also the science of a lot of brain-unhealthy ingredients. In the latter case, probably things you already knew to stay away from, but still, it’s a good reminder of one more reason why.

Nor does she merely sort things into brain-healthy (or brain-unhealthy, or brain-neutral), but rather she gives lists of “this for memory” and “this against depression” and “this for cognition” and “this against stress” and so forth.

Perhaps the greatest value of this book is in that; her clear explanations with science that’s simplified but not dumbed down. The recipes are definitely great too, though!

Bottom line: if you’d like to eat more for brain health, this book will give you many ways of doing so

Click here to check out Food for Thought, and upgrade your recipes!

Don’t Forget…

Did you arrive here from our newsletter? Don’t forget to return to the email to continue learning!

Learn to Age Gracefully

Join the 98k+ American women taking control of their health & aging with our 100% free (and fun!) daily emails: