The Ultimate Booster

10almonds is reader-supported. We may, at no cost to you, receive a portion of sales if you purchase a product through a link in this article.

Winning The Biological Arms Race

The human immune system (and indeed, other immune systems, but we are all humans here, after all) is in a constant state of war with pathogens, and that war is a constant biological arms race:

- We improve our defenses and destroy the attackers; the 1% of pathogens that survived now “know” how to counter that trick.

- The pathogens wreak havoc in our systems; the n% of us that survive now have immune systems that “know” how to counter that trick.

Vaccines are a mighty tool in our favor here, because they’re the technology that stops our n% from also being a very low number.

With vaccines, we can effectively pass on established defenses onto the population at large, as this cute video explains very well and very simply in 57 seconds:

Click Here If The Embedded Video Doesn’t Load Automatically!

The problem with vaccines

The problem is that this accelerates the arms race. It’s like a chess game where we are able to respond to every move quickly (which is good for us), and/but this means passing the move over to our opponent sooner.

That problem’s hard to avoid, because the alternative has always been “let people die in much larger numbers”.

Traditional vs mRNA vaccines

A quick refresher before we continue to the big news of the day:

- Traditional vaccines use a disabled version of a pathogen to trigger an immune response that will teach the body to recognize the pathogen ready for when the full version shows up

- mRNA vaccines use a custom-made bit of genetic information to tell the body to make its own harmless fake pathogen and then respond to the harmless fake pathogen it made.

Note: this happens independently of the host’s DNA, so no, it does not change your DNA

See also: The Truth About Vaccines

Here’s a more detailed explainer (with a helpful diagram) using the COVID mRNA vaccine as an example:

Genome.gov | How does an mRNA vaccine work?

However, this still leaves us “chasing strains”, because as the pathogen (in this case, a virus) adapts, the vaccine has to be updated too, hence all the boosters.

This is a lot like a security update for your computer’s antivirus software. They’re annoying, but they do an important job.

No more “chasing strains”

The press conference soundbite on this sums it up well:

❝Scientists at UC Riverside have demonstrated a new, RNA-based vaccine strategy that is effective against any strain of a virus and can be used safely even by babies or the immunocompromised.❞

Read in full: Vaccine breakthrough means no more chasing strains

You may be wondering: what makes this one effective against any strain?

❝What I want to emphasize about this vaccine strategy is that it is broad.

It is broadly applicable to any number of viruses, broadly effective against any variant of a virus, and safe for a broad spectrum of people. This could be the universal vaccine that we have been looking for.

Viruses may mutate in regions not targeted by traditional vaccines. However, we are targeting their whole genome with thousands of small RNAs. They cannot escape this.❞

Importantly, this means it can be applied not just to one disease, let alone just one strain of COVID. Rather, it can be used for a wide variety of viruses that have similar viral functions—COVID / SARS in general, including influenza, and even viruses such as dengue.

How it does this: the above article explains in more detail, but in few words: it targets tiny strings of the genome that are present in all strains of the virus.

Illustrative example: if you wanted to block 10almonds (please don’t), you could block our email address.

But if we were malicious (we’re not) we could be sneaky and change it, so you’d have to block the new one, and the cycle repeats.

But if you were block all emails containing the tiny string of characters “10almonds”, changing our email address would no longer penetrate your defenses.

Now imagine also blocking strings such as “One-Minute Book Review” and “Today’s almonds have been activated by” and other strings we use in every email.

Now multiply this by thousands of strings (because genomes are much larger than our little newsletter), and you see its effectiveness!

Great! How can I get this?

It’s still in the testing stages for now; this is “breaking news” science, after all.

The study itself

…is paywalled for now, sadly, but if you happen to have institutional access, here it is:

Take care!

Don’t Forget…

Did you arrive here from our newsletter? Don’t forget to return to the email to continue learning!

Recommended

Learn to Age Gracefully

Join the 98k+ American women taking control of their health & aging with our 100% free (and fun!) daily emails:

-

Simply The Pits: These Underarm Myths!

10almonds is reader-supported. We may, at no cost to you, receive a portion of sales if you purchase a product through a link in this article.

Are We Taking A Risk To Smell Fresh As A Daisy?

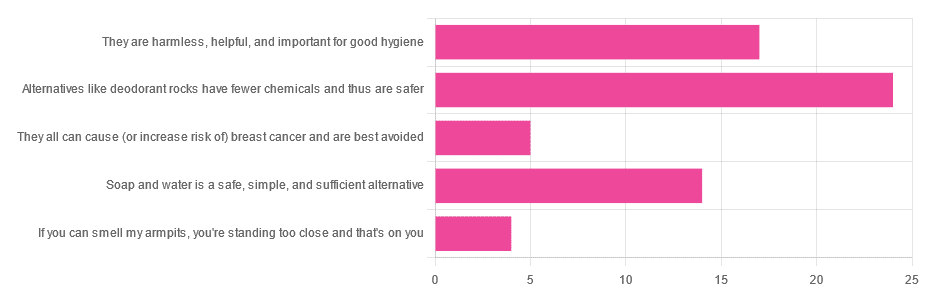

Yesterday, we asked you for your health-related view of underarm deodorants.

So, what does the science say?

They can cause (or increase risk of) cancer: True or False?

False, so far as we know. Obviously it’s very hard to prove a negative, but there is no credible evidence that deodorants cause cancer.

The belief that they do comes from old in vitro studies applying the deodorant directly to the cells in question, like this one with canine kidney tissues in petri dishes:

Antiperspirant Induced DNA Damage in Canine Cells by Comet Assay

Which means that if you’re not a dog and/or if you don’t spray it directly onto your internal organs, this study’s data doesn’t apply to you.

In contrast, more modern systematic safety reviews have found…

❝Neither is there clear evidence to show use of aluminum-containing underarm antiperspirants or cosmetics increases the risk of Alzheimer’s Disease or breast cancer.

Metallic aluminum, its oxides, and common aluminum salts have not been shown to be either genotoxic or carcinogenic.❞

(however, one safety risk it did find is that we should avoid eating it excessively while pregnant or breastfeeding)

Alternatives like deodorant rocks have fewer chemicals and thus are safer: True or False?

True and False, respectively. That is, they do have fewer chemicals, but cannot in scientific terms be qualifiably, let alone quantifiably, described as safer than a product that was already found to be safe.

Deodorant rocks are usually alum crystals, by the way; that is to say, aluminum salts of various kinds. So if it was aluminum you were hoping to avoid, it’s still there.

However, if you’re trying to cut down on extra chemicals, then yes, you will get very few in deodorant rocks, compared to the very many in spray-on or roll-on deodorants!

Soap and water is a safe, simple, and sufficient alternative: True or False?

True or False, depending on what you want as a result!

- If you care that your deodorant also functions as an antiperspirant, then no, soap and water will certainly not have an antiperspirant effect.

- If you care only about washing off bacteria and eliminating odor for the next little while, then yes, soap and water will work just fine.

Bonus myths:

There is no difference between men’s and women’s deodorants, apart from the marketing: True or False?

False! While to judge by the marketing, the only difference is that one smells of “evening lily” and the other smells of “chainsaw barbecue” or something, the real difference is…

- The “men’s” kind is designed to get past armpit hair and reach the skin without clogging the hair up.

- The “women’s” kind is designed to apply a light coating to the skin that helps avoid chafing and irritation.

In other words… If you are a woman with armpit hair or a man without, you might want to ignore the marketing and choose according to your grooming preferences.

Hopefully you can still find a fragrance that suits!

Shaving (or otherwise depilating) armpits is better for hygiene: True or False?

True or False, depending on what you consider “hygiene”.

Consistent with popular belief, shaving means there is less surface area for bacteria to live. And empirically speaking, that means a reduction in body odor:

However, shaving typically causes microabrasions, and while there’s no longer hair for the bacteria to enjoy, they now have access to the inside of your skin, something they didn’t have before. This can cause much more unpleasant problems in the long-run, for example:

❝Hidradenitis suppurativa is a chronic and debilitating skin disease, whose lesions can range from inflammatory nodules to abscesses and fistulas in the armpits, groin, perineum, inframammary region❞

Read more: Hidradenitis suppurativa: Basic considerations for its approach: A narrative review

And more: Hidradenitis suppurativa: Epidemiology, clinical presentation, and pathogenesis

If this seems a bit “damned if you do; damned if you don’t”, this writer’s preferred way of dodging both is to use electric clippers (the buzzy kind, as used for cutting short hair) to trim hers down low, and thus leave just a little soft fuzz.

What you do with yours is obviously up to you; our job here is just to give the information for everyone to make informed decisions whatever you choose 🙂

Take care!

Share This Post

-

The Many Faces Of Cosmetic Surgery

10almonds is reader-supported. We may, at no cost to you, receive a portion of sales if you purchase a product through a link in this article.

Cosmetic Surgery: What’s The Truth?

In Tuesday’s newsletter, we asked you your opinion on elective cosmetic surgeries, and got the above-depicted, below-described, set of responses:

- About 48% said “Everyone should be able to get what they want, assuming informed consent”

- About 28% said “It can ease discomfort to bring features more in line with normalcy”

- 15% said “They should be available in the case of extreme disfigurement only”

- 10% said “No elective cosmetic surgery should ever be performed; needless danger”

Well, there was a clear gradient of responses there! Not so polarizing as we might have expected, but still enough dissent for discussion

So what does the science say?

The risks of cosmetic surgery outweigh the benefits: True or False?

False, subjectively (but this is important).

You may be wondering: how is science subjective?

And the answer is: the science is not subjective, but people’s cost:worth calculations are. What’s worth it to one person absolutely may not be worth it to another. Which means: for those for whom it wouldn’t be worth it, they are usually the people who will not choose the elective surgery.

Let’s look at some numbers (specifically, regret rates for various surgeries, elective/cosmetic or otherwise):

- Regret rate for elective cosmetic surgery in general: 20%

- Regret rate for knee replacement (i.e., not cosmetic): 17.1%

- Regret rate for hip replacement (i.e., not cosmetic): 4.8%

- Regret rate for gender-affirming surgeries (for transgender patients): 1%

So we can see, elective surgeries have an 80–99% satisfaction rate, depending on what they are. In comparison, the two joint replacements we mentioned have a 82.9–95.2% satisfaction rate. Not too dissimilar, taken in aggregate!

In other words: if a person has studied the risks and benefits of a surgery and decides to go ahead, they’re probably going to be happy with the results, and for them, the benefits will have outweighed the risks.

Sources for the above numbers, by the way:

- What is the regret rate for plastic surgery?

- Decision regret after primary hip and knee replacement surgery

- A systematic review of patient regret after surgery—a common phenomenon in many specialties but rare within gender-affirmation surgery

But it’s just a vanity; therapy is what’s needed instead: True or False?

False, generally. True, sometimes. Whatever the reasons for why someone feels the way they do about their appearance—whether their face got burned in a fire or they just have triple-J cups that they’d like reduced, it’s generally something they’ve already done a lot of thinking about. Nevertheless, it does also sometimes happen that it’s a case of someone hoping it’ll be the magical solution, when in reality something else is also needed.

How to know the difference? One factor is whether the surgery is “type change” or “restorative”, and both have their pros and cons.

- In “type change” (e.g. rhinoplasty), more psychological adjustment is needed, but when it’s all over, the person has a new nose and, statistically speaking, is usually happy with it.

- In “restorative” (e.g. facelift), less psychological adjustment is needed (as it’s just a return to a previous state), so a person will usually be happy quickly, but ultimately it is merely “kicking the can down the road” if the underlying problem is “fear of aging”, for example. In such a case, likely talking therapy would be beneficial—whether in place of, or alongside, cosmetic surgery.

Here’s an interesting paper on that; the sample sizes are small, but the discussion about the ideas at hand is a worthwhile read:

Does cosmetic surgery improve psychosocial wellbeing?

Some people will never be happy no matter how many surgeries they get: True or False?

True! We’re going to refer to the above paper again for this one. In particular, here’s what it said about one group for whom surgeries will not usually be helpful:

❝There is a particular subgroup of people who appear to respond poorly to cosmetic procedures. These are people with the psychiatric disorder known as “body dysmorphic disorder” (BDD). BDD is characterised by a preoccupation with an objectively absent or minimal deformity that causes clinically significant distress or impairment in social, occupational, or other areas of functioning.

For several reasons, it is important to recognise BDD in cosmetic surgery settings:

Firstly, it appears that cosmetic procedures are rarely beneficial for these people. Most patients with BDD who have had a cosmetic procedure report that it was unsatisfactory and did not diminish concerns about their appearance.

Secondly, BDD is a treatable disorder. Serotonin-reuptake inhibitors and cognitive behaviour therapy have been shown to be effective in about two-thirds of patients with BDD❞

~ Dr. David Castle et al. (lightly edited for brevity)

Which is a big difference compared to, for example, someone having triple-J breasts that need reducing, or the wrong genitals for their gender, or a face whose features are distinct outliers.

Whether that’s a reason people with BDD shouldn’t be able to get it is an ethical question rather than a scientific one, so we’ll not try to address that with science.

After all, many people (in general) will try to fix their woes with a haircut, a tattoo, or even a new sportscar, and those might sometimes be bad decisions, but they are still the person’s decision to make.

And even so, there can be protectionist laws/regulations that may provide a speed-bump, for example:

Take care!

Share This Post

-

Avoid Knee Surgery With This Proven Strategy (Over-50s Specialist Physio)

10almonds is reader-supported. We may, at no cost to you, receive a portion of sales if you purchase a product through a link in this article.

A diagnosis of knee arthritis can be very worrying, but it doesn’t necessarily mean a knee replacement surgery is inevitable. Here’s how to keep your knee better, for longer (and potentially, for life):

Flexing your good health

You know we wouldn’t let that “proven” go by unchallenged if it weren’t, so what’s the evidence for it? Research (papers linked in the video description) showed 70% of patients (so, not 100%, but 70% is good odds and a lot better than the alternative) with mild to moderate knee arthritis avoided surgery after following a specific protocol—the one we’re about to describe.

The key strategy is to focus on strengthening the quadriceps muscles for joint protection, as strong quads correlate with reduced pain. However, a full range of motion in the knee is essential for optimal quad function, so that needs attention too, and in fact is foundational (can’t strengthen a quadriceps that doesn’t have a range of motion available to it):

Steps to follow:

- Improve knee extension:

- Passive knee extension exercise: gently press your knee down while lying flat, to increase straightening.

- Weighted heel props: use light weights to encourage gradual knee straightening.

- Enhance knee flexion:

- Use a towel to gently pull the knee towards the body to improve bending range.

Regular practice (multiple times daily) leads to improved knee function and pain relief. Exercises should be performed gently and without pain, aiming for consistent, gradual progress.And of course, if you do experience pain, it is recommend to consult with a local physiotherapist for more personalized guidance.

For more on all of this plus visual demonstrations, enjoy:

Click Here If The Embedded Video Doesn’t Load Automatically!

Want to learn more?

You might also like to read:

Treat Your Own Knee – by Robin McKenzie

Take care!

Share This Post

- Improve knee extension:

Related Posts

-

Taurine’s Benefits For Heart Health And More

10almonds is reader-supported. We may, at no cost to you, receive a portion of sales if you purchase a product through a link in this article.

Taurine: Research Review

First, what is taurine, beyond being an ingredient in many energy drinks?

It’s an amino acid that many animals, including humans, can synthesize in our bodies. Some other animals—including obligate carnivores such as cats (but not dogs, who are omnivorous by nature) cannot synthesize taurine and must get it from food.

So, as humans are very versatile omnivorous frugivores by nature, we have choices:

- Synthesize it—no need for any conscious action; it’ll just happen

- Eat it—by eating meat, which contains taurine

- Supplement it—by taking supplements, including energy drinks, which generally (but not always) use a bioidentical lab-made taurine. Basically, lab-made taurine is chemically identical to the kind found in meat, it’s just cheaper and doesn’t involve animals as a middleman.

What does it do?

Taurine does a bunch of essential things, including:

- Maintaining hydration/electrolyte balance in cells

- Regulating calcium/magnesium balance in cells

- Forming bile salts, which are needed for digestion

- Supporting the integrity of the central nervous system

- Regulating the immune system and antioxidative processes

Thus, a shortage of taurine can lead to such issues as kidney problems, eye tissue damage (since the eyes are a particularly delicate part of the CNS), and cardiomyopathy.

If you want to read more, here’s an academic literature review:

Taurine: A “very essential” amino acid

On the topic of eye health, a 2014 study found that taurine is the most plentiful amino acid in the eye, and helps protect against retinal degeneration, in which they say:

❝We here review the evidence for a role of taurine in retinal ganglion cell survival and studies suggesting that this compound may be involved in the pathophysiology of glaucoma or diabetic retinopathy. Along with other antioxidant molecules, taurine should therefore be seriously reconsidered as a potential treatment for such retinal diseases❞

Read more: Taurine: the comeback of a neutraceutical in the prevention of retinal degenerations

Taurine for muscles… In more than sports!

We’d be remiss not to mention that taurine is enjoyed by athletes to enhance athletic performance; indeed, it’s one of its main selling-points:

See: Taurine in sports and exercise

But! It’s also useful for simply maintaining skeleto-muscular health in general, and especially in the context of age-related decline and chronic disease:

Taurine: the appeal of a safe amino acid for skeletal muscle disorders

On the topic of safety… How safe is it?

There’s an interesting answer to that question. Within safe dose ranges (we’ll get to that), taurine is not only relatively safe, but also, studies that looked to explore its risks found new benefits in the process. Specifically of interest to us were that it appears to promote better long-term memory, especially as we get older (as taurine levels in the brain decline with age):

Taurine, Caffeine, and Energy Drinks: Reviewing the Risks to the Adolescent Brain

^Notwithstanding the title, we assure you, the research got there; they said:

❝Interestingly, the levels of taurine in the brain decreased significantly with age, which led to numerous studies investigating the potential neuroprotective effects of supplemental taurine in several different experimental models❞

What experimental models were those? These ones:

- Taurine protects cerebellar neurons of the external granular layer

- Effects of taurine on alterations of neurobehavior and neurodevelopment key proteins expression

- Neuroprotective role of taurine in developing offspring affected by maternal alcohol consumption

…which were all animal studies, however.

The same systematic review also noted that not only was more research needed on humans, but also, existing studies have had a strong bias to male physiology (in both human and assorted other animal studies), so more diverse study is needed too.

What are the safe dose ranges?

Before we get to toxicity, let’s look at some therapeutic doses. In particular, some studies that found that 500mg 3x daily, i.e. 1.5g total daily, had benefits for heart health:

- Taurine and atherosclerosis

- The Anti-Inflammatory Effect of Taurine on Cardiovascular Disease

- Taurine supplementation has anti-atherogenic and anti-inflammatory effects before and after incremental exercise in heart failure

- Taurine Supplementation Lowers Blood Pressure and Improves Vascular Function in Prehypertension

- Taurine improves the vascular tone through the inhibition of TRPC3 function in the vasculature

Bottom line on safety: 3g/day has been found to be safe:

Don’t Forget…

Did you arrive here from our newsletter? Don’t forget to return to the email to continue learning!

Learn to Age Gracefully

Join the 98k+ American women taking control of their health & aging with our 100% free (and fun!) daily emails:

-

Cold Medicines & Heart Health

10almonds is reader-supported. We may, at no cost to you, receive a portion of sales if you purchase a product through a link in this article.

Cold Medicines & Heart Health

In the wake of many decongestants disappearing from a lot of shelves after a common active ingredient being declared useless*, you may find yourself considering alternative decongestants at this time of year.

*In case you missed it:

It doesn’t seem to be dangerous, by the way, just also not effective:

FDA Panel Says Common OTC Decongestant, Phenylephrine, Is Useless

Good for your nose, bad for your heart?

With products based on phenylephrine out of the running, products based on pseudoephedrine, a competing drug, are enjoying a surge in popularity.

Good news: pseudoephedrine works!

Bad news: pseudoephedrine works because it is a vasoconstrictor, and that vasoconstriction reduces nasal swelling. That same vasoconstriction also raises overall blood pressure, potentially dangerously, depending on an assortment of other conditions you might have.

Further reading: Can decongestants spike your blood pressure? What to know about hypertension and cold medicine

Who’s at risk?

The warning label, unread by many, reads:

❝Do not use this product if you have heart disease, high blood pressure, thyroid disease, diabetes, or difficulty in urination due to enlargement of the prostate gland, unless directed by a doctor❞

Source: Harvard Health | Don’t let decongestants squeeze your heart

What are the other options?

The same source as above recommends antihistamines as an option to be considered, citing:

❝Antihistamines such as […] cetirizine (Zyrtec) and loratadine (Claritin) can help with a stuffy nose and are safe for the heart.❞

But we’d be remiss not to mention drug-free options too, for example:

- Saline rinse with a neti pot or similar

- Use of a humidifier in your house/room

- Steam inhalation, with or without eucalyptus etc

See also: Inhaled Eucalyptus’s Immunomodulatory and Antimicrobial Effects

Take care!

Don’t Forget…

Did you arrive here from our newsletter? Don’t forget to return to the email to continue learning!

Learn to Age Gracefully

Join the 98k+ American women taking control of their health & aging with our 100% free (and fun!) daily emails:

-

Yes, blue light from your phone can harm your skin. A dermatologist explains

10almonds is reader-supported. We may, at no cost to you, receive a portion of sales if you purchase a product through a link in this article.

Social media is full of claims that everyday habits can harm your skin. It’s also full of recommendations or advertisements for products that can protect you.

Now social media has blue light from our devices in its sights.

So can scrolling on our phones really damage your skin? And will applying creams or lotions help?

Here’s what the evidence says and what we should really be focusing on.

Max kegfire/Shutterstock Remind me, what actually is blue light?

Blue light is part of the visible light spectrum. Sunlight is the strongest source. But our electronic devices – such as our phones, laptops and TVs – also emit it, albeit at levels 100-1,000 times lower.

Seeing as we spend so much time using these devices, there has been some concern about the impact of blue light on our health, including on our eyes and sleep.

Now, we’re learning more about the impact of blue light on our skin.

How does blue light affect the skin?

The evidence for blue light’s impact on skin is still emerging. But there are some interesting findings.

1. Blue light can increase pigmentation

Studies suggest exposure to blue light can stimulate production of melanin, the natural skin pigment that gives skin its colour.

So too much blue light can potentially worsen hyperpigmentation – overproduction of melanin leading to dark spots on the skin – especially in people with darker skin.

Blue light can worsen dark spots on the skin caused by overproduction of melanin. DUANGJAN J/Shutterstock 2. Blue light can give you wrinkles

Some research suggests blue light might damage collagen, a protein essential for skin structure, potentially accelerating the formation of wrinkles.

A laboratory study suggests this can happen if you hold your device one centimetre from your skin for as little as an hour.

However, for most people, if you hold your device more than 10cm away from your skin, that would reduce your exposure 100-fold. So this is much less likely to be significant.

3. Blue light can disrupt your sleep, affecting your skin

If the skin around your eyes looks dull or puffy, it’s easy to blame this directly on blue light. But as we know blue light affects sleep, what you’re probably seeing are some of the visible signs of sleep deprivation.

We know blue light is particularly good at suppressing production of melatonin. This natural hormone normally signals to our bodies when it’s time for sleep and helps regulate our sleep-wake cycle.

By suppressing melatonin, blue light exposure before bed disrupts this natural process, making it harder to fall asleep and potentially reducing the quality of your sleep.

The stimulating nature of screen content further disrupts sleep. Social media feeds, news articles, video games, or even work emails can keep our brains active and alert, hindering the transition into a sleep state.

Long-term sleep problems can also worsen existing skin conditions, such as acne, eczema and rosacea.

Sleep deprivation can elevate cortisol levels, a stress hormone that breaks down collagen, the protein responsible for skin’s firmness. Lack of sleep can also weaken the skin’s natural barrier, making it more susceptible to environmental damage and dryness.

Can skincare protect me?

The beauty industry has capitalised on concerns about blue light and offers a range of protective products such as mists, serums and lip glosses.

From a practical perspective, probably only those with the more troublesome hyperpigmentation known as melasma need to be concerned about blue light from devices.

This condition requires the skin to be well protected from all visible light at all times. The only products that are totally effective are those that block all light, namely mineral-based suncreens or some cosmetics. If you can’t see the skin through them they are going to be effective.

But there is a lack of rigorous testing for non-opaque products outside laboratories. This makes it difficult to assess if they work and if it’s worth adding them to your skincare routine.

What can I do to minimise blue light then?

Here are some simple steps you can take to minimise your exposure to blue light, especially at night when it can disrupt your sleep:

- use the “night mode” setting on your device or use a blue-light filter app to reduce your exposure to blue light in the evening

- minimise screen time before bed and create a relaxing bedtime routine to avoid the types of sleep disturbances that can affect the health of your skin

- hold your phone or device away from your skin to minimise exposure to blue light

- use sunscreen. Mineral and physical sunscreens containing titanium dioxide and iron oxides offer broad protection, including from blue light.

In a nutshell

Blue light exposure has been linked with some skin concerns, particularly pigmentation for people with darker skin. However, research is ongoing.

While skincare to protect against blue light shows promise, more testing is needed to determine if it works.

For now, prioritise good sun protection with a broad-spectrum sunscreen, which not only protects against UV, but also light.

Michael Freeman, Associate Professor of Dermatology, Bond University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Don’t Forget…

Did you arrive here from our newsletter? Don’t forget to return to the email to continue learning!

Learn to Age Gracefully

Join the 98k+ American women taking control of their health & aging with our 100% free (and fun!) daily emails: