Why Many Nonprofit (Wink, Wink) Hospitals Are Rolling in Money

10almonds is reader-supported. We may, at no cost to you, receive a portion of sales if you purchase a product through a link in this article.

One owns a for-profit insurer, a venture capital company, and for-profit hospitals in Italy and Kazakhstan; it has just acquired its fourth for-profit hospital in Ireland. Another owns one of the largest for-profit hospitals in London, is partnering to build a massive training facility for a professional basketball team, and has launched and financed 80 for-profit start-ups. Another partners with a wellness spa where rooms cost $4,000 a night and co-invests with “leading private equity firms.”

Do these sound like charities?

These diversified businesses are, in fact, some of the country’s largest nonprofit hospital systems. And they have somehow managed to keep myriad for-profit enterprises under their nonprofit umbrella — a status that means they pay little or no taxes, float bonds at preferred rates, and gain numerous other financial advantages.

Through legal maneuvering, regulatory neglect, and a large dollop of lobbying, they have remained tax-exempt charities, classified as 501(c)(3)s.

“Hospitals are some of the biggest businesses in the U.S. — nonprofit in name only,” said Martin Gaynor, an economics and public policy professor at Carnegie Mellon University. “They realized they could own for-profit businesses and keep their not-for-profit status. So the parking lot is for-profit; the laundry service is for-profit; they open up for-profit entities in other countries that are expressly for making money. Great work if you can get it.”

Many universities’ most robust income streams come from their technically nonprofit hospitals. At Stanford University, 62% of operating revenue in fiscal 2023 was from health services; at the University of Chicago, patient services brought in 49% of operating revenue in fiscal 2022.

To be sure, many hospitals’ major source of income is still likely to be pricey patient care. Because they are nonprofit and therefore, by definition, can’t show that thing called “profit,” excess earnings are called “operating surpluses.” Meanwhile, some nonprofit hospitals, particularly in rural areas and inner cities, struggle to stay afloat because they depend heavily on lower payments from Medicaid and Medicare and have no alternative income streams.

But investments are making “a bigger and bigger difference” in the bottom line of many big systems, said Ge Bai, a professor of health care accounting at the Johns Hopkins University Bloomberg School of Public Health. Investment income helped Cleveland Clinic overcome the deficit incurred during the pandemic.

When many U.S. hospitals were founded over the past two centuries, mostly by religious groups, they were accorded nonprofit status for doling out free care during an era in which fewer people had insurance and bills were modest. The institutions operated on razor-thin margins. But as more Americans gained insurance and medical treatments became more effective — and more expensive — there was money to be made.

Not-for-profit hospitals merged with one another, pursuing economies of scale, like joint purchasing of linens and surgical supplies. Then, in this century, they also began acquiring parts of the health care systems that had long been for-profit, such as doctors’ groups, as well as imaging and surgery centers. That raised some legal eyebrows — how could a nonprofit simply acquire a for-profit? — but regulators and the IRS let it ride.

And in recent years, partnerships with, and ownership of, profit-making ventures have strayed further and further afield from the purported charitable health care mission in their community.

“When I first encountered it, I was dumbfounded — I said, ‘This not charitable,’” said Michael West, an attorney and senior vice president of the New York Council of Nonprofits. “I’ve long questioned why these institutions get away with it. I just don’t see how it’s compliant with the IRS tax code.” West also pointed out that they don’t act like charities: “I mean, everyone knows someone with an outstanding $15,000 bill they can’t pay.”

Hospitals get their tax breaks for providing “charity care and community benefit.” But how much charity care is enough and, more important, what sort of activities count as “community benefit” and how to value them? IRS guidance released this year remains fuzzy on the issue.

Academics who study the subject have consistently found the value of many hospitals’ good work pales in comparison with the value of their tax breaks. Studies have shown that generally nonprofit and for-profit hospitals spend about the same portion of their expenses on the charity care component.

Here are some things listed as “community benefit” on hospital systems’ 990 tax forms: creating jobs; building energy-efficient facilities; hiring minority- or women-owned contractors; upgrading parks with lighting and comfortable seating; creating healing gardens and spas for patients.

All good works, to be sure, but health care?

What’s more, to justify engaging in for-profit business while maintaining their not-for-profit status, hospitals must connect the business revenue to that mission. Otherwise, they pay an unrelated business income tax.

“Their CEOs — many from the corporate world — spout drivel and turn somersaults to make the case,” said Lawton Burns, a management professor at the University of Pennsylvania’s Wharton School. “They do a lot of profitable stuff — they’re very clever and entrepreneurial.”

The truth is that a number of not-for-profit hospitals have become wealthy diversified business organizations. The most visible manifestation of that is outsize executive compensation at many of the country’s big health systems. Seven of the 10 most highly paid nonprofit CEOs in the United States run hospitals and are paid millions, sometimes tens of millions, of dollars annually. The CEOs of the Gates and Ford foundations make far less, just a bit over $1 million.

When challenged about the generous pay packages — as they often are — hospitals respond that running a hospital is a complicated business, that pharmaceutical and insurance execs make much more. Also, board compensation committees determine the payout, considering salaries at comparable institutions as well as the hospital’s financial performance.

One obvious reason for the regulatory tolerance is that hospital systems are major employers — the largest in many states (including Massachusetts, Pennsylvania, Minnesota, Arizona, and Delaware). They are big-time lobbying forces and major donors in Washington and in state capitals.

But some patients have had enough: In a suit brought by a local school board, a judge last year declared that four Pennsylvania hospitals in the Tower Health system had to pay property taxes because its executive pay was “eye popping” and it demonstrated “profit motives through actions such as charging management fees from its hospitals.”

A 2020 Government Accountability Office report chided the IRS for its lack of vigilance in reviewing nonprofit hospitals’ community benefit and recommended ways to “improve IRS oversight.” A follow-up GAO report to Congress in 2023 said, “IRS officials told us that the agency had not revoked a hospital’s tax-exempt status for failing to provide sufficient community benefits in the previous 10 years” and recommended that Congress lay out more specific standards. The IRS declined to comment for this column.

Attorneys general, who regulate charity at the state level, could also get involved. But, in practice, “there is zero accountability,” West said. “Most nonprofits live in fear of the AG. Not hospitals.”

Today’s big hospital systems do miraculous, lifesaving stuff. But they are not channeling Mother Teresa. Maybe it’s time to end the community benefit charade for those that exploit it, and have these big businesses pay at least some tax. Communities could then use those dollars in ways that directly benefit residents’ health.

KFF Health News is a national newsroom that produces in-depth journalism about health issues and is one of the core operating programs at KFF—an independent source of health policy research, polling, and journalism. Learn more about KFF.

Subscribe to KFF Health News’ free Morning Briefing.

Don’t Forget…

Did you arrive here from our newsletter? Don’t forget to return to the email to continue learning!

Recommended

Learn to Age Gracefully

Join the 98k+ American women taking control of their health & aging with our 100% free (and fun!) daily emails:

-

Your friend has been diagnosed with cancer. Here are 6 things you can do to support them

10almonds is reader-supported. We may, at no cost to you, receive a portion of sales if you purchase a product through a link in this article.

Across the world, one in five people are diagnosed with cancer during their lifetime. By age 85, almost one in two Australians will be diagnosed with cancer.

When it happens to someone you care about, it can be hard to know what to say or how to help them. But providing the right support to a friend can make all the difference as they face the emotional and physical challenges of a new diagnosis and treatment.

Here are six ways to offer meaningful support to a friend who has been diagnosed with cancer.

1. Recognise and respond to emotions

When facing a cancer diagnosis and treatment, it’s normal to experience a range of emotions including fear, anger, grief and sadness. Your friend’s moods may fluctuate. It is also common for feelings to change over time, for example your friend’s anxiety may decrease, but they may feel more depressed.

Spending time together can mean a lot to someone who is feeling isolated during cancer treatment. Chokniti-Studio/Shutterstock Some friends may want to share details while others will prefer privacy. Always ask permission to raise sensitive topics (such as changes in physical appearance or their thoughts regarding fears and anxiety) and don’t make assumptions. It’s OK to tell them you feel awkward, as this acknowledges the challenging situation they are facing.

When they feel comfortable to talk, follow their lead. Your support and willingness to listen without judgement can provide great comfort. You don’t have to have the answers. Simply acknowledging what has been said, providing your full attention and being present for them will be a great help.

2. Understand their diagnosis and treatment

Understanding your friend’s diagnosis and what they’ll go through when being treated may be helpful.

Being informed can reduce your own worry. It may also help you to listen better and reduce the amount of explaining your friend has to do, especially when they’re tired or overwhelmed.

Explore reputable sources such as the Cancer Council website for accurate information, so you can have meaningful conversations. But keep in mind your friend has a trusted medical team to offer personalised and accurate advice.

3. Check in regularly

Cancer treatment can be isolating, so regular check-ins, texts, calls or visits can help your friend feel less alone.

Having a normal conversation and sharing a joke can be very welcome. But everyone copes with cancer differently. Be patient and flexible in your support – some days will be harder for them than others.

Remembering key dates – such as the next round of chemotherapy – can help your friend feel supported. Celebrating milestones, including the end of treatment or anniversary dates, may boost morale and remind your friend of positive moments in their cancer journey.

Always ask if it’s a good time to visit, as your friend’s immune system may be compromised by their cancer or treatments such as chemotherapy or radiotherapy. If you’re feeling unwell, it’s best to postpone visits – but they may still appreciate a call or text.

4. Offer practical support

Sometimes the best way to show your care is through practical support. There may be different ways to offer help, and what your friend needs might change at the beginning, during and after treatment.

For example, you could offer to pick up prescriptions, drive them to appointments so they have transport and company to debrief, or wait with them at appointments.

Meals will always be welcome. However it’s important to remember cancer and its treatments may affect taste, smell and appetite, as well as your friend’s ability to eat enough or absorb nutrients. You may want to check first if there are particular foods they like. Good nutrition can help boost their strength while dealing with the side effects of treatment.

There may also be family responsibilities you can help with, for example, babysitting kids, grocery shopping or taking care of pets.

There may be practical ways you can help, such as dropping off meals. David Trinks/Unsplash 5. Explore supports together

Studies have shown mindfulness practices can be an effective way for people to manage anxiety associated with a cancer diagnosis and its treatment.

If this is something your friend is interested in, it may be enjoyable to explore classes (either online or in-person) together.

You may also be able to help your friend connect with organisations that provide emotional and practical help, such as the Cancer Council’s support line, which offers free, confidential information and support for anyone affected by cancer, including family, friends and carers.

Peer support groups can also reduce your friend’s feelings of isolation and foster shared understanding and empathy with people who’ve gone through a similar experience. GPs can help with referrals to support programs.

6. Stick with them

Be committed. Many people feel isolated after their treatment. This may be because regular appointments have reduced or stopped – which can feel like losing a safety net – or because their relationships with others have changed.

Your friend may also experience emotions such as worry, lack of confidence and uncertainty as they adjust to a new way of living after their treatment has ended. This will be an important time to support your friend.

But don’t forget: looking after yourself is important too. Making sure you eat well, sleep, exercise and have emotional support will help steady you through what may be a challenging time for you, as well as the friend you love.

Our research team is developing new programs and resources to support carers of people who live with cancer. While it can be a challenging experience, it can also be immensely rewarding, and your small acts of kindness can make a big difference.

Stephanie Cowdery, Research Fellow, Carer Hub: A Centre of Excellence in Cancer Carer Research, Translation and Impact, Deakin University; Anna Ugalde, Associate Professor & Victorian Cancer Agency Fellow, Deakin University; Trish Livingston, Distinguished Professor & Director of Special Projects, Faculty of Health, Deakin University, and Victoria White, Professor of Pyscho-Oncology, School of Psychology, Deakin University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Share This Post

-

Why Some People Get Sick More (And How To Not Be One Of Them)

10almonds is reader-supported. We may, at no cost to you, receive a portion of sales if you purchase a product through a link in this article.

Some people have never yet had COVID (so far so good, this writer included); others are on their third bout already; others have not been so lucky and are no longer with us to share their stories.

Obviously, even the healthiest and/or most careful person can get sick, and it would be folly to be complacent and think “I’m not a person who gets sick; that happens to other people”.

Nor is COVID the only thing out there to worry about; there’s always the latest outbreak-du-jour of something, and there are always the perennials such as cold and flu—which are also not to be underestimated, because both weaken us to other things, and flu has killed very many, from the 50,000,000+ in the 1918 pandemic, to the 700,000ish that it kills each year nowadays.

And then there are the combination viruses:

Move over, COVID and Flu! We Have “Hybrid Viruses” To Contend With Now

So, why are some people more susceptible?

Firstly, some people are simply immunocompromised. This means for example that:

- perhaps they have an inflammatory/autoimmune disease of some kind (e.g. lupus, rheumatoid arthritis, type 1 diabetes), or…

- perhaps they are taking immunosuppressants for some reason (e.g. because they had an organ transplant), or…

- perhaps they have a primary infection that leaves them vulnerable to secondary infections. Most infections will do this to some degree or another, but some are worse for it than others; untreated HIV is a clear example. The HIV itself may not kill people, but (if untreated) the resultant AIDS will leave a person open to being killed by almost any passing opportunistic pathogen. Pneumonia of various kinds being high on the list, but it could even be something as simple as the common cold, without a working immune system to fight it.

See also: How To Prevent (Or Reduce) Inflammation

And for that matter, since pneumonia is a very common last-nail-in-the-coffin secondary infection (especially: older people going into hospital with one thing, getting a secondary infection and ultimately dying as a result), it’s particularly important to avoid that, so…

See also: Pneumonia: What We Can & Can’t Do About It

Secondly, some people are not immunocompromised per the usual definition of the word, but their immune system is, arguably, compromised.

Cortisol, the stress hormone, is an immunosuppressant. We need cortisol to live, but we only need it in small bursts here and there (such as when we are waking up the morning). When high cortisol levels become chronic, so too does cortisol’s immunosuppressant effect.

Top things that cause elevated cortisol levels include:

- Stress

- Alcohol

- Smoking

Thus, the keys here are to 1) not smoke 2) not drink, ideally, or at least keep consumption low, but honestly even one drink will elevate cortisol levels, so it’s better not to, and 3) manage stress.

See also: Lower Your Cortisol! (Here’s Why & How)

Other modifiable factors

Being aware of infection risk and taking steps to reduce it (e.g. avoiding being with many people in confined indoor places, masking as appropriate, handwashing frequently) is a good preventative strategy, along with of course getting any recommended vaccines as they come available.

What if they fail? How can we boost the immune system?

We talked about not sabotaging the immune system, but what about actively boosting it? The answer is yes, we certainly can (barring serious medical reasons why not), as there are some very important lifestyle factors too:

Beyond Supplements: The Real Immune-Boosters!

One final last-line thing…

Since if we do get an infection, it’s better to know sooner rather than later… A recent study shows that wearable activity trackers can (if we pay attention to the right things) help predict disease, including highlighting COVID status (positive or negative) about as accurately (88% accuracy) as rapid screening tests. Here’s a pop-science article about it:

Wearable activity trackers show promise in detecting early signals of disease

Take care!

Share This Post

-

Kiwi vs Passion Fruit – Which is Healthier?

10almonds is reader-supported. We may, at no cost to you, receive a portion of sales if you purchase a product through a link in this article.

Our Verdict

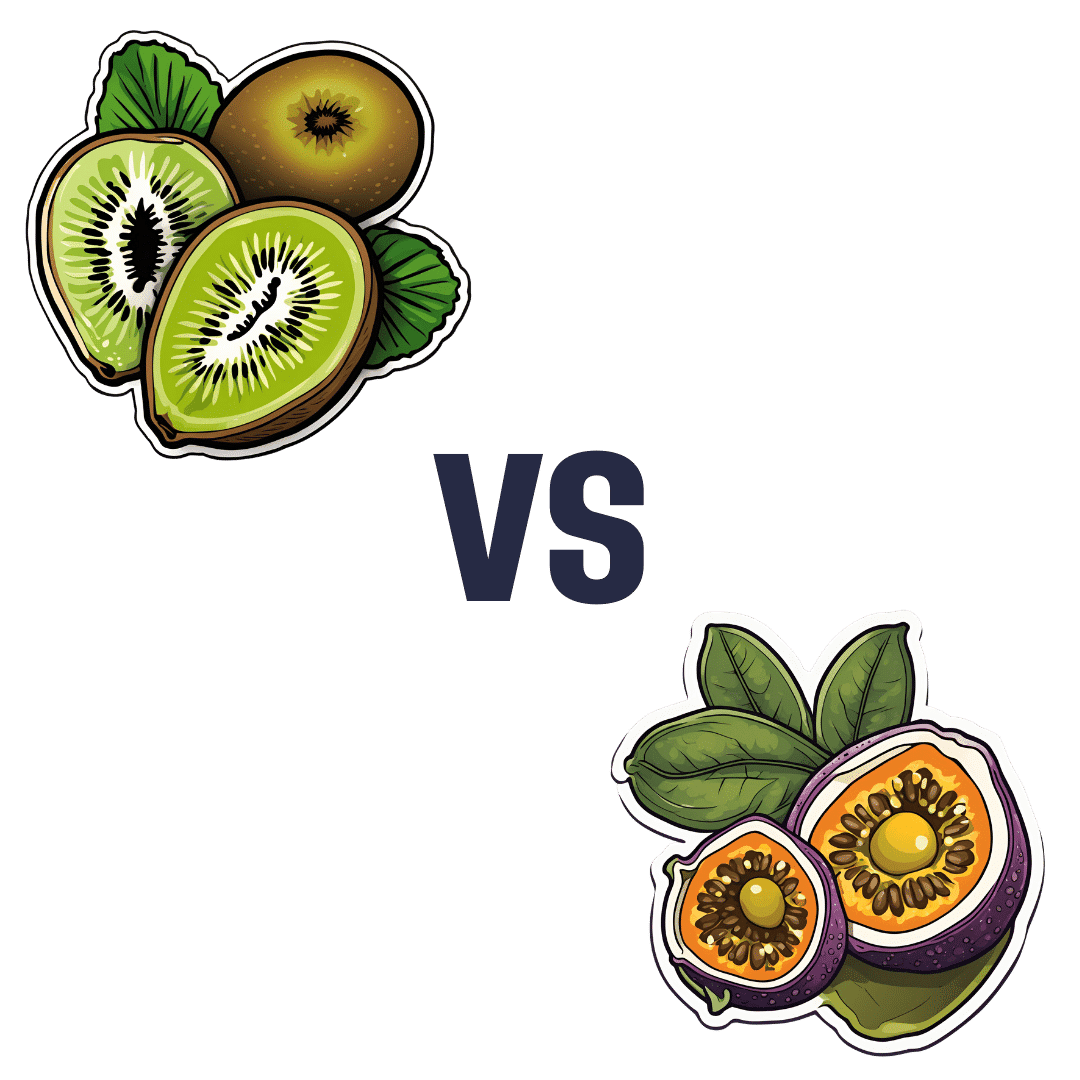

When comparing kiwi to passion fruit, we picked the passion fruit.

Why?

This fruit is so passionate about delivery nutrient-dense goodness, that at time of writing, nothing has beaten it yet!

In terms of macros, passion fruit has a little more protein, as well as 50% more carbs, and/but more than 3x the fiber. That last stat is particularly impressive, and also results in passion fruit having a much lower glycemic index, too. In short, a clear win for passion fruit in the macros category.

In the category of vitamins, kiwi has more of vitamins B9, C, E, and K, while passion fruit has more of vitamins A, B2, B3, and B6, making for a tie this time.

As for minerals, kiwi has more calcium, copper, manganese, and zinc, while passion fruit has more iron, magnesium, phosphorus, potassium, and selenium, resulting in a modest, marginal win for passion fruit in this category.

Adding up the categories gives a convincing win for passion fruit, but by all means enjoy either or both; diversity is good! And kiwi has its merits too (for example, it’s particularly high in vitamin K, appropriately enough).

Want to learn more?

You might like to read:

Top 8 Fruits That Prevent & Kill Cancer

Enjoy!

Share This Post

Related Posts

-

Vit D + Calcium: Too Much Of A Good Thing?

10almonds is reader-supported. We may, at no cost to you, receive a portion of sales if you purchase a product through a link in this article.

Vit D + Calcium: Too Much Of A Good Thing?

- Myth: you can’t get too much calcium!

- Myth: you must get as much vitamin D as possible!

Let’s tackle calcium first:

❝Calcium is good for you! You need more calcium for your bones! Be careful you don’t get calcium-deficient!❞

Contingently, those comments seem reasonable. Contingently on you not already having the right amount of calcium. Most people know what happens in the case of too little calcium: brittle bones, osteoporosis, and so forth.

But what about too much?

Hypercalcemia

Having too much calcium—or “hypercalcemia”— can lead to problems with…

- Groans: gastrointestinal pain, nausea, and vomiting. Peptic ulcer disease and pancreatitis.

- Bones: bone-related pains. Osteoporosis, osteomalacia, arthritis and pathological fractures.

- Stones: kidney stones causing pain.

- Moans: refers to fatigue and malaise.

- Thrones: polyuria, polydipsia, and constipation

- Psychic overtones: lethargy, confusion, depression, and memory loss.

(mnemonic courtesy of Sadiq et al, 2022)

What causes this, and how do we avoid it? Is it just dietary?

It’s mostly not dietary!

Overconsumption of calcium is certainly possible, but not common unless one has an extreme diet and/or over-supplementation. However…

Too much vitamin D

Again with “too much of a good thing”! While keeping good levels of vitamin D is, obviously, good, overdoing it (including commonly prescribed super-therapeutic doses of vitamin D) can lead to hypercalcemia.

This happens because vitamin D triggers calcium absorption into the gut, and acts as gatekeeper to the bloodstream.

Normally, the body only absorbs 10–20% of the calcium we consume, and that’s all well and good. But with overly high vitamin D levels, the other 80–90% can be waved on through, and that is very much Not Good™.

See for yourself:

- Hypercalcemia of Malignancy: An Update on Pathogenesis and Management

- Vitamin D-Mediated Hypercalcemia: Mechanisms, Diagnosis, and Treatment

How much is too much?

The United States’ Office of Dietary Supplements defines 4000 IU (100μg) as a high daily dose of vitamin D, and recommends 600 IU (15μg) as a daily dose, or 800 IU (20μg) if aged over 70.

See for yourself: Vitamin D Fact Sheet for Health Professionals ← there’s quite a bit of extra info there too

Don’t Forget…

Did you arrive here from our newsletter? Don’t forget to return to the email to continue learning!

Learn to Age Gracefully

Join the 98k+ American women taking control of their health & aging with our 100% free (and fun!) daily emails:

-

Quit Drinking – by Rebecca Dolton

10almonds is reader-supported. We may, at no cost to you, receive a portion of sales if you purchase a product through a link in this article.

Many “quit drinking” books focus on tips you’ve heard already—cut down like this, rearrange your habits like that, make yourself accountable like so, add a reward element this way, etc.

Dolton takes a different approach.

She focuses instead on the underlying processes of addiction, so as to not merely understand them to fight them, but also to use them against the addiction itself.

This is not just a social or behavioral analysis, by the way, and goes into some detail into the physiological factors of the addiction—including such things as the little-talked about relationship between addiction and gut flora. Candida albans, found in most if not all humans to some extent, gets really out of control when given certain kinds of sugars (including those from alcohol); it grows, eventually puts roots through the intestinal walls (ouch!) and the more it grows, the more it demands the sugars it craves, so the more you feed it.

Quite a motivator to not listen to such cravings! It’s not even you that wants it, it’s the Candida!

Anyway, that’s just one example; there are many. The point here is that this is a well-researched, well-written book that sets itself apart from many of its genre.

Don’t Forget…

Did you arrive here from our newsletter? Don’t forget to return to the email to continue learning!

Learn to Age Gracefully

Join the 98k+ American women taking control of their health & aging with our 100% free (and fun!) daily emails:

-

Sweet Cinnamon vs Regular Cinnamon – Which is Healthier?

10almonds is reader-supported. We may, at no cost to you, receive a portion of sales if you purchase a product through a link in this article.

Our Verdict

When comparing sweet cinnamon to regular cinnamon, we picked the sweet.

Why?

In this case, it’s not close. One of them is health-giving and the other is poisonous (but still widely sold in supermarkets, especially in the US and Canada, because it is cheaper).

It’s worth noting that “regular cinnamon” is a bit of a misnomer, since sweet cinnamon is also called “true cinnamon”. The other cinnamon’s name is formally “cassia cinnamon”, but marketers don’t tend to call it that, preferring to calling it simply “cinnamon” and hope consumers won’t ask questions about what kind, because it’s cheaper.

Note: this too is especially true in the US and Canada, where for whatever reason sweet cinnamon seems to be more difficult to obtain than in the rest of the world.

In short, both cinnamons contain cinnamaldehyde and coumarin, but:

- Sweet/True cinnamon contains only trace amounts of coumarin

- Regular/Cassia cinnamon contains about 250x more coumarin

Coumarin is heptatotoxic, meaning it poisons the liver, and the recommended safe amount is 0.1mg/kg, so it’s easy to go over that with just a couple of teaspoons of cassia cinnamon.

You might be wondering: how can they get away with selling something that poisons the liver? In which case, see also: the alcohol aisle. Selling toxic things is very common; it just gets normalized a lot.

Cinnamaldehyde is responsible for cinnamon’s healthier properties, and is found in reasonable amounts in both cinnamons. There is about 50% more of it in the regular/cassia than in the sweet/true, but that doesn’t come close to offsetting the potential harm of its higher coumarin content.

Want to learn more?

You may like to read:

- A Tale Of Two Cinnamons ← this one has more of the science of coumarin toxicity, as well as discussing (and evidencing) cinnamaldehyde’s many healthful properties against inflammation, cancer, heart disease, neurodegeneration, etc

Enjoy!

Don’t Forget…

Did you arrive here from our newsletter? Don’t forget to return to the email to continue learning!

Learn to Age Gracefully

Join the 98k+ American women taking control of their health & aging with our 100% free (and fun!) daily emails: